America is heading back to school. Teachers are looking for thousands of missing kids.

LOS ANGELES – Outside a bustling Target last Tuesday, a señora with a broad white visor and a handful of colorful flyers waited for anyone to approach who looked like a parent.

“Do you have kids in school?” she asked in Spanish as masked families wheeled out bags of snacks and cases of Topo Chico. “Need information about school?”

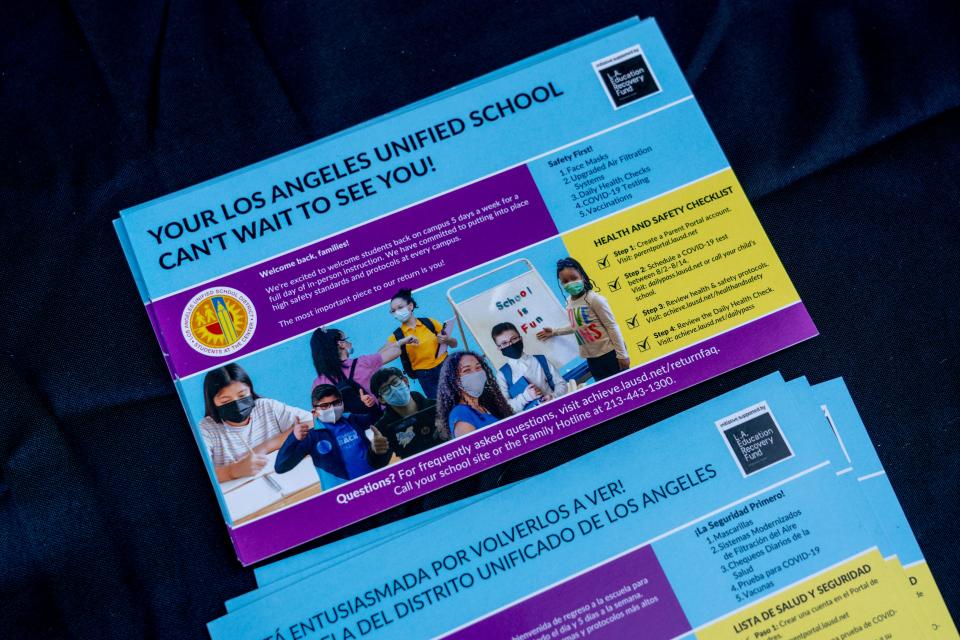

Given a nod, Hilda Martinez, a persuasive grandmother, handed over a card with information about a momentous, if tenuous, date for the nation’s second-largest school district.

After more than a year and a half of at-home learning, Los Angeles children are set to return to school buildings Monday, but nobody knows how many will actually show up. While some students logged in from home and tried their best with the pandemic's online schooling, thousands disappeared altogether.

They rarely signed into online courses. Never turned in an assignment. Never appeared in Zoom videos. Their schools have no idea where they are – or even, in some cases, whether they still live in the U.S.

In communities across the country, educators and leaders have embarked on an unprecedented quest to find missing students, in hopes of reengaging them in formal education – before it's too late.

But coming back to school poses formidable hurdles. To attend in person, Los Angeles students must arrive with a negative coronavirus test Monday and pass a daily health screener – steps dozens of parents didn't know about when Martinez waved them down last week.

Beyond the procedural items, a more infectious variant of the coronavirus has landed more children in hospitals, heightening health fears about returning kids to schools. Low-income Latinos – who make up the majority of Los Angeles Unified families – are still reeling from being the epicenter of the worst COVID-19 outbreak in the country. Many are also suspicious of the protection offered by COVID-19 shots, and they worry government records for the shots will lead to immigration problems for their families.

On top of those fears, parents here are out of the habit of sending their children to school. Los Angeles never opened middle or high schools last year, and many students took jobs instead. Los Angeles Unified staff have texted and written to parents and knocked on doors of students, a district spokeswoman said.

Nonprofit groups helping to find kids say more aggressive and coordinated outreach efforts are necessary. They have little information about who has committed to return and which parents need more coaxing.

Eleven days before the start of school, Los Angeles education nonprofit Great Public Schools Now mobilized Gerry Guzman, a political strategist with deep ties in the Latino community, to apply tactics of getting out the vote to getting kids back to school. Guzman paid Martinez and other community organizers to distribute flyers outside major stores and to blanket low-income neighborhoods with informational door hangers.

“Why is that important?" he said. "Because we need those students to get their education."

Falling behind at home

Over the next few weeks, most of the nation's school districts will open for fully in-person instruction – a push urged by everyone from President Joe Biden's administration to national teachers unions to parents, especially those who work full-time. Health and education experts have stressed the academic and social benefits of in-person learning.

But how many will return is still a mystery. Los Angeles enrollment fell by 24,877 students in elementary school and 6,421 students in middle school from June 2019 to June 2021, according to district figures requested by USA TODAY.

Some of those students disappeared because they formally exited to home schooling. Kindergarten enrollment drops were particularly steep, largely because many parents skipped it altogether.

“Everyone’s wondering if there’s going to be a bus that shows up somewhere with all the missing kindergartners on Monday,” said Drew Furedi, president and CEO of Para Los Niños, a nonprofit that runs charter schools, early education centers and programs for disconnected young people. The organization normally has a kindergarten cohort of 70. Only 58 were enrolled the week before school started.

Still, many Latino parents in Los Angeles said they'd continue to keep their kids home this year if they could, because it felt safer.

“If it was up to me I'd keep them virtual this year,” said Ashley Rosales, 28. Her children, 7 and 8, fell behind in online learning, she said. She could help them at home when her job as a life skills coach for young adults with disabilities also went remote. But now she's back to work in person and has no choice but to return them to their schools.

Rosales also didn't know her kids would need proof of a negative coronavirus test on Monday, until she received a flyer from Martinez outside Target in Pacoima, a city in the San Fernando Valley.

Back-to-school protocols: Which states require masks, vaccines in school?

Teachers and education experts say it's imperative to get children back in school because most students, particularly those struggling before the pandemic, learn more in person than they do at home. On average nationwide, students are about five months behind in math and four months behind in reading, according to a study released in July by management consulting firm McKinsey & Company.

In schools educating large numbers of poor students, normal reading progress lagged even more. And the test results came only from kids who were attending school.

“The kids who did not get back to school this spring, we still don't know what's happening with their learning,” said Emma Dorn, McKinsey's global education practice manger.

“Maybe some will return to school. Others may be lost to the school system and may drop out altogether.”

In Los Angeles, 1 out of 3 students weren't engaged online last fall, according to an analysis of district data by Great Public Schools Now.

“They didn't learn well virtually,” Maricruz Flores, a mother in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles, said of her children, 16 and 9. "But I'm scared. I'd rather have them at home where they are safe.”

Los Angeles' students are enrolled in person this year by default, but their parents can opt into the district's virtual option. About 12,500 students, or roughly 3% of the district's total enrollment, had signed up for the virtual option by the end of last week, according to the office of Kelly Gonez, president of the Los Angeles Unified School Board.

Creative efforts to nudge in-person school – and vaccines

Some agencies tasked with finding families have taken to combining vaccine outreach with back-to-school efforts. For example, a community organizer with InnerCity Struggle in the Eastside neighborhood of Los Angeles stopped Flores on the street in Boyle Heights to talk about vaccines. The organizers helped her schedule a vaccination appointment for herself and her teenage child, and they handed her a flyer in Spanish about school reopening.

But after 2½ hours walking door-to-door in Boyle Heights, that was the only meaningful conversation the organizers had with a parent about schools.

Nonprofits trying to find students say they're challenged by not having addresses of students who have disappeared or disengaged. Leaders say they understand it's for privacy purposes, but that means door-to-door efforts are generally driven by ZIP codes targeted by the district or by census data that indicates where the parents of school-age children live.

The American Federation of Teachers, the second-largest national teachers union, paid teachers $25 an hour this summer to knock on doors and coax parents back to school. They were guided by a phone application that combined public voter registration information with an algorithm that identified the homes of possible public school parents.

Staff with the United Federation of Teachers in New York City knocked on almost 1,800 doors by mid-August and talked with more than 700 parents in those visits, according to figures from the union. More than 60% of parents said safety amid COVID-19 was their biggest concern. A minority, 6%, said they were opposed to going back, but New York City schools are not offering a remote option.

Justin Spiro, a school social worker in New York City, knocked on doors in Queens and the Bronx, persuading parents to send their kids back to class. He took the canvassing gig because he knows children learn better in person – and he can't be nearly as effective at his job on Zoom, he said.

Spiro has worked in his own school building, Maspeth High School, for 13 months, following masking and other safety protocols. That experience helped him offer families firsthand advice about how schools can operate safely in person, he said.

But some just wanted someone to listen to their concerns.

“These kids were remote all last year, and in some cases, this was their parents' first face-to-face conversation with a school official for 18 months,” Spiro said.

"Some were worried that their kids were really far behind in algebra. Others wanted to know if there would be counselors back in school.”

Where are the missing kids?

Some of the missing kindergarten students will show up in first grade this year. But convincing older students who dropped out may be very difficult – even if not finishing high school may diminish their long-term career prospects.

Ratcheting up partnerships between the district and social service agencies will be necessary to reach those students, nonprofit leaders say.

“There’s a community of providers out there who are really connected with families, and who could be very responsive, but we haven't been activated on a grand scale,” said Mayra Ceballos, the chief program officer of El Centro Del Pueblo, an agency that provides support services to low-income Latino families.

Others acknowledge the district's distinct challenges. It's huge – with more than 500,000 students – which makes it difficult to pivot to new initiatives quickly. It has been shuttered since March 2020 to all students in middle and high school. Elementary schools opened for some in-person learning at the end of last school year, but only for a few hours a day. And a district leadership transition has begun. Former Superintendent Austin Beutner resigned at the end of last school year.

"This is the first time LAUSD has fully opened in an entire year," said Ana Ponce, executive director of Great Public Schools Now. "It makes sense that they're not prioritizing looking for kids right now because reopening alone is a huge lift."

Getting kids in schools at the start of any year is generally a major concern because enrollment determines a district's funding. But large amounts of federal relief money have temporarily eased some of the typical budget concerns, Ponce said. District leaders may wait to see which kids return while monitoring operations amid the delta variant. Then they'll likely tackle tracking down those who don't return, Ponce said.

Back outside the Target in Pacoima last week, Guzman, the political strategist, talked with a father who said all the coronavirus testing appointments at his child's school were booked solid.

"What should I do?" he asked.

Guzman eventually gave the father, Joel Reynozo, the name of the school his own middle school daughter attends. Guzman had read the school was accepting walk-up appointments of all district children. Reynozo thanked him and added that he was eager to see his son return to school. But, he said, he does not intend to have his son vaccinated when he's eligible.

Reynozo said he didn't trust the district, didn't trust the government and didn't trust that enough research had gone into the vaccine.

Safe for young people? What the CDC says about heart problems and the COVID vaccine

That response worried Guzman, but at least he could help make sure Reynozo's son got tested in time for in-person class Monday.

Guzman is an accomplished political operative, although his record is blemished by allegations of improper conduct from several years ago. During the pandemic, even his own daughter missed a bunch of assignments in online learning, he said. He worries about the academic progress of children from families who face far steeper challenges.

“We could end up with a whole lost generation of students – early dropouts, that breaks my heart,” he said.

Through Sunday, Guzman and his community organizers were slated to blanket many of the district's 107 targeted ZIP codes with 40,000 door hangers. They hoped it would be enough.

“It's absolutely go time,” Guzman said.

Early childhood education coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from Save the Children. Save the Children does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: As America heads back to school, thousands of kids are missing