America's Fascination With the Western Genre Tells Us Who We Are—and Who We're Not

Shortly after his father, Western author Louis L'Amour's death in 1988, Beau L'Amour found a large room filled with loose papers and books.

"There was just all kinds of incredible stuff. It was just piled up almost at random and there was kind of a little path about 14 inches wide that led to his desk," Beau said of what he found in L'Amour's writing room. "Then there was an area about four feet around where he could turn his chair around and stuff."

It's in that room where Beau found that one of the most prolific and popular writers of all time still had stories to tell. These unpublished works have consumed Beau's life for the last 30 years. He's spent three decades sorting through and publishing and finishing his father's lost work. These have been published as short stories, in a series called Louis L'Amour's Lost Treasures, and, most recently, No Traveller Returns, on which the father and son share a byline.

Throughout the 20th century, Louis defined the Western genre. At the time of his death, he'd published 89 novels, dozens of which have been adapted to film and television. And his own life and legend was as big as the stories he told-he fought in WWII, he boxed professionally, he sailed the world and joined the circus. His early adventures inspired the literary tale of the high seas in No Traveller Returns.

If you've seen or read any sort of Western in the last century, it may have been either written by Louis or inspired by his work.

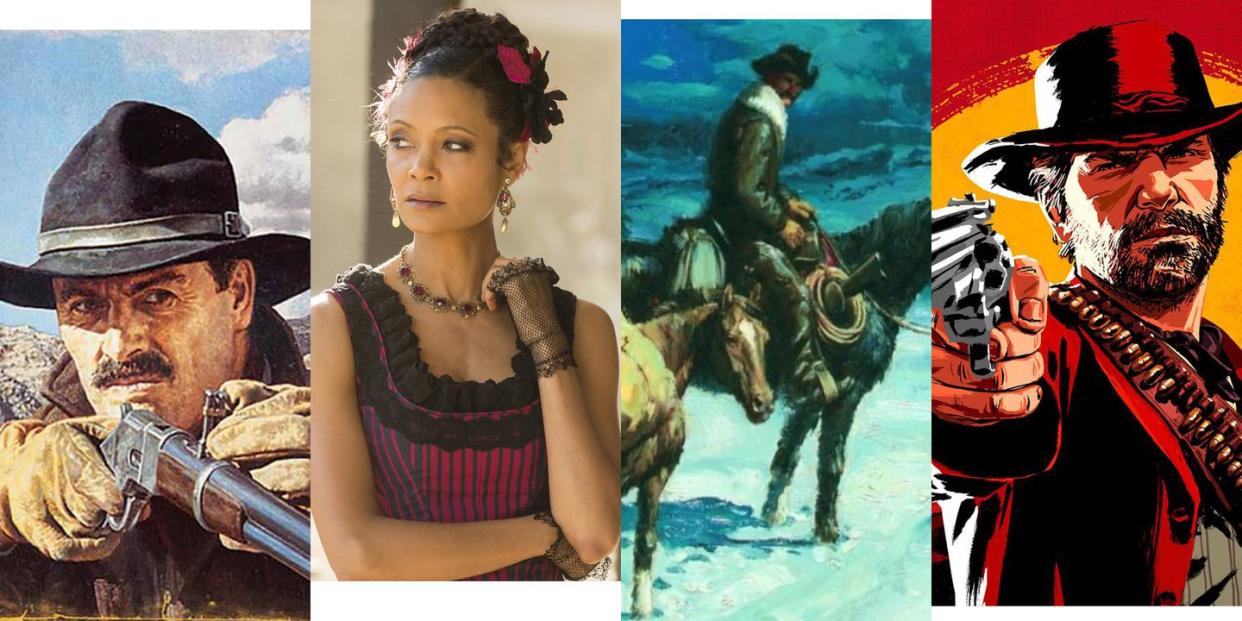

And today, as Beau continues his father's legacy, the Western remains stronger than ever. From massively popular video games like Red Dead Redemption 2 to hit TV shows like Westworld to prestige films like the Coen Brothers's Ballad of Buster Scruggs, the Western genre has become the stuff of critical and financial success.

We caught up with Beau to discuss his father's legacy and the past, present, and future of the Western genre.

The popularity of the genre stretches all the way back to actual Western times.

The Western genre goes back to the time when it wasn't something about the past. Westerns were a very popular portion of the adventure literature of the 1870s and '80s. Westerns didn't disappear or appear, or anything like that. They've kind of ebbed and flowed over the years. I think that Westerns have also ebbed and flowed in different mediums for different reasons.

Westerns were easy to make, so Hollywood flooded the market with them in the mid-20th century.

I think Western movies and television were not necessarily popular, but they were presented to audiences as entertainment by Hollywood because they were fairly inexpensive to make until 1960 or so-you went to Burbank and it was just fields. It didn't require any serious location work and things like that. I think that at different times, the Western has had different things to say about who we are as a nation or who we're not. I think this "who we're not" part is interesting when it comes to that increase in Westerns immediately after World War Two, which I'd say ended in 1960s. The Western was about what we weren't and people wanted an exciting adventure genre, but they didn't necessarily want to get flashbacks to World War Two or Korea.

In the '60s and '70s the Western even became part of counterculture when Louis was most popular.

[Louis] was the most popular in the late 1970s. I think some of it was that he was a guy that was successful enough to hang on into that period, but also, that was a period when counterculture took on the Western. And you would see it in Rock and Roll with the Eagles and Buffalo Springfield and Jackson Browne and in fashion. At a certain point, hippie fashion became high pull-on boots and vests and Indian braids. There was a point where the rebellion of the 1960s started seeing aspects of the West in itself. People wanted to get away from stifling, Victorian, East Coast culture and get out into the wilds where they could be free, where they could do what they wanted to do, where they could live without people looking over their shoulder and telling them what to think and telling them what to say.

No Traveller Returns is one of L'Amour's first novels, and is very different from his later work.

In the beginning, Dad wrote No Traveler Returns and a series of short stories that are very much like it. They are quite literary. And he wasn't able to make any money on those things. He started writing a bit more blood and thunder-extra stories for the pulps and things like that which were much more escapist and lots of fun, but not quite so high quality. And that was how he made his living after the war. He went back into that business but was writing Westerns. Then, because of the failure of the magazines, he had to turn his career to writing paperback original Westerns. And that was quite a struggle. Maybe seven years before I was born, my dad was living in a bedroom in the back of somebody else's apartment.

In 2018, the Western genre has seen a boom because people are trying to escape.

The Western... explores the friction between civilization and not-civilization. It's something that we, as a culture, we have to deal with vastly less these days than we ever had. When you're naked and alone in the wilderness, you are confronting the uncompromising. You can't make a deal with it. On a completely other level, math is uncompromising. I think so many things in our culture we have created this kind of netherworld that we can live in where we're sort of in it, and sort of not in it, and we can negotiate with it and things like that. I think a lot of times that's what happens when life becomes as civilized as it is today. Thus, a lot of fiction, a lot of entertainment is gonna head toward places that take us somewhere else.

People loved L'Amour's work because his writing was one step ahead of the reader.

Dad taught himself to write directly out of his unconscious. He would just literally walk up to the typewriter, sit down, and start writing. Many of the novels he wrote he literally just wrote them one page at a time from the beginning to the end, and then he sent it to the publisher. He just typed it out five-to ten pages a day and very little planning, no rewriting and that was the way it came out. And, it took a lot of practice to get to the point where he could do that. It's very tough to get your unconscious to the point where it can open at will and play those kinds of tricks for you, which is terrific. I think a reading audience can sense that they are moments behind my dad. Their experience of reading it is because of the way he wrote it down, is just seconds later than the moment he thought of it. I think a lot of the reason they liked Louis is not the genre, but the energy.

('You Might Also Like',)