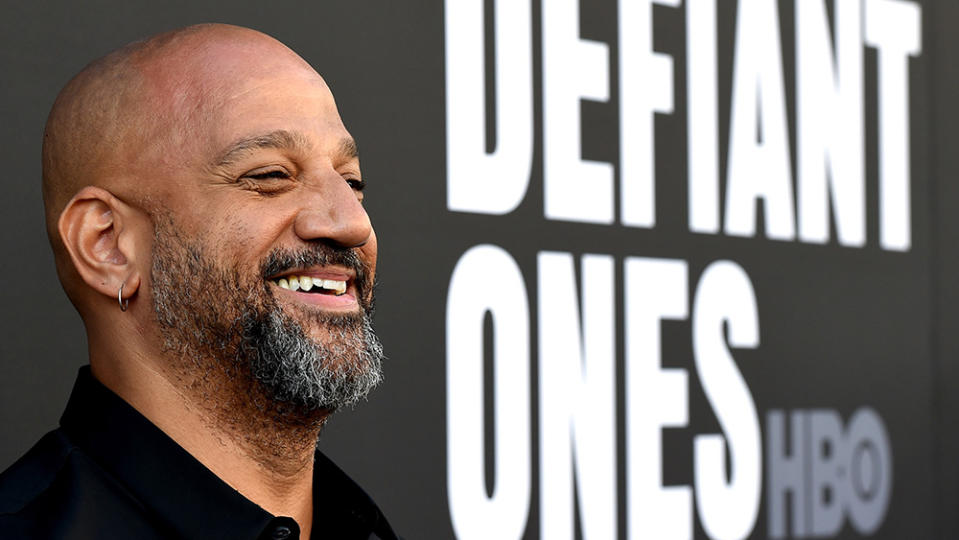

Allen Hughes On TIFF Premiere Of Tupac Shakur Docuseries ‘Dear Mama’; How Filmmaker Confronts Own Beat Down At Hands Of Tupac & Entourage Onscreen

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

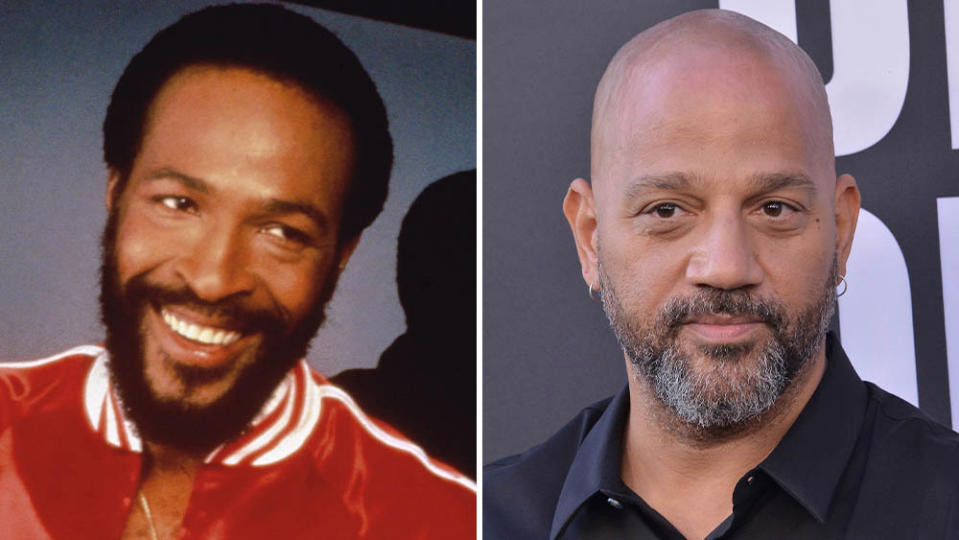

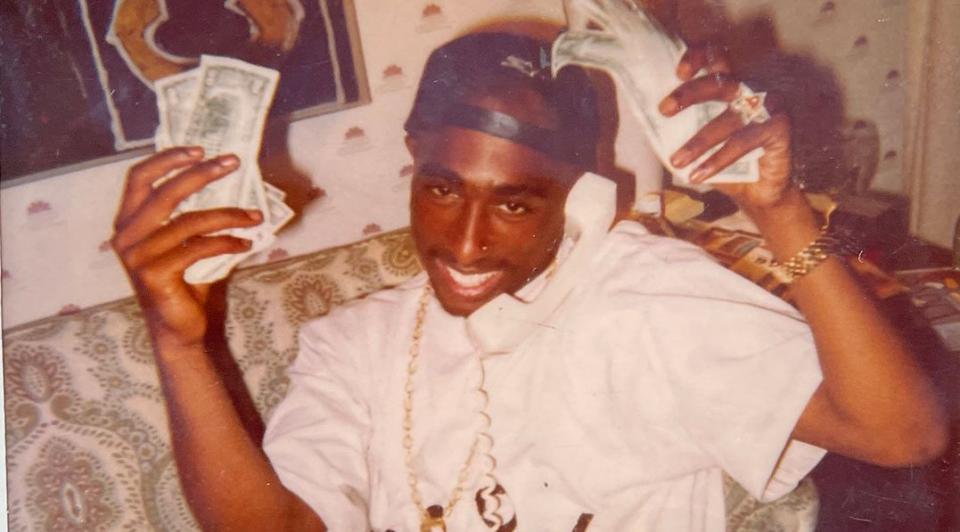

EXCLUSIVE: This morning in Toronto, writer-director Allen Hughes and FX unveil the first of their five-part docuseries Dear Mama. This is an epic exploration of the life of hip-hop icon Tupac Shakur and his late mom, Afeni Shakur, the former Black Panthers member. It is Hughes’ first trip back to TIFF since he and brother Albert came to unveil their Johnny Depp pic From Hell, only to see that title become all too apt when, on their media day 21 years ago, everything got canceled when two hijacked planes crashed into and took down the Twin Towers. At the behest of the estate of the Shakur family, Hughes — who, aside from films like The Book of Eli, directed the acclaimed docuseries The Defiant Ones on Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine — spent years diving deep into the mythology of Tupac to answer why his art endures so long after he was shot dead in 1996 at age 25. Much as he would have preferred to avoid it, Hughes had to confront his own provocative history with Tupac. After the Hughes Brothers hired Tupac for a supporting role in Menace II Society, they fired him over disagreements about the part he wanted to play. Later, the hip-hop artist and his pals crossed paths with Hughes and his co-director Albert, and beat them badly enough that it led to a criminal conviction on Shakur for assault and battery. Here, Hughes discusses all, including the spiritual connection between Tupac and Marvin Gaye, whose life Allen Hughes takes on next in a narrative film for Warner Bros and Motown Records.

DEADLINE: When we were first talking about your five-part deep dive into Tupac Shakur’s life, you were calling it Outlaw. Why the change to Dear Mama?

More from Deadline

ALLEN HUGHES: When I agreed to do this, after speaking to the family and the estate, I always saw it as a mother and son’s story, because I could relate to the single mother as an activist thing. That was my mother; she was on the forefront of the women’s rights movement, and we were involved in all that. It was always Outlaw, but I didn’t want to call it that, and Dear Mama was better.

DEADLINE: Why?

Getty Images

HUGHES: I realized, I said, “Well, wait a minute. This is Tupac’s love note to his mother, and my love note to my mother.” As you see an Episode 1, she narrates the piece ethereally. When you think about times we’re in, and what just happened with the Supreme Court’s ruling on Roe v Wade and what it means for women’s rights and human rights, it’s all a civil rights struggle. Afeni and Tupac’s journey together, the title Dear Mama means to me what they stood for. I wanted the audience to see why this is a timely, eternal struggle where, even when you get to the mountaintop, you have to stay vigilant to maintain the wins. Tupac’s song “Dear Mama” just encapsulated this is about that woman’s struggle with those human rights. It’s all connected.

DEADLINE: It also gives more importance to Shakur’s standing as an artist than the violence that seemed to surround his life…

HUGHES: You’re absolutely correct. It also occurred to me on this journey that his original art and her original art is poetry. And Outlaw didn’t signify that, at all.

DEADLINE: Unfortunately, many hip-hop artists died young in violent incidents. Few reached the iconic status that Shakur did in his brief life. You see his image on a shirt and you know exactly who he is, like Bob Marley or Marilyn Monroe or James Dean. I recall reading about him getting shot, or in trouble, and think, “Why doesn’t he get away from this life and live more safely?” But maybe the environment was fuel for the art?

HUGHES: I want to articulate this the right way. Episode 1 is purely a setup. And then the series takes off. It becomes a musical odyssey and gets into the psychology of what you just said. His thing was, “I gotta meet these people in the streets. I gotta meet these gangsters in the streets.” His plan was to organize them, like the Panthers did. That was the plan. Before his life was cut short at 25, he would always say the thug life thing was about meeting these gangsters and street, the street elements, these young men he was not condescending to.

DEADLINE: What was the biggest benefit you got making that deal with the estate of Tupac and Afeni?

HUGHES: Access. Not only to all the poetry, all the writings, but also the recordings and the a cappella of Tupac. They gave us the ability to move away the noise and bring out the poetry. When I say noise, back to Outlaw versus Dear Mama, how do you bring the poetry out in all this? How do you understand that? You’ll see that in Part 2, and people who’ve seen it were like, “I never realized he was saying that.” The estate granting access to the vaults — all the writings, jewelry, all the clothes — those are all his stuff. He kept logs and diaries on his ambitions, and Afeni would also note things as well. So you could excavate and know, whether it was ’91 or ‘92, what was he feeling? What was she feeling? But the challenge with her, there wasn’t a lot of recordings of her, particularly when it comes to her history. We had to dig.

DEADLINE: Your style in the first episode is to stay in the background. But you got beat up pretty badly by Tupac and his entourage, lingering anger from you firing him from Menace II Society, your first feature with your brother Albert. It ended with Tupac being found guilty of assault and battery. How do you explore that incident?

TIFF

HUGHES: I was reluctant to go into my thing cuz I was like, I don’t want the camera on me. I’m not trying to be famous in this thing. My producers and writing partner said, “You gotta deal with it, Allen.” So we found a way and you’ll see it in Part 2. And it was cathartic for me, because I understood things about what happened that favor him, actually, and don’t favor my argument, that I never understood before. Not the argument for violence, but what the disagreement was over.

DEADLINE: Can you elaborate?

HUGHES: Like Tupac, we were young and having a difficult time. We didn’t have time to get into it while he was a part of Menace II Society as a cast member, and it just boiled over to where we had to part ways or I had to let him go. Then, months later, he retaliated. But what I didn’t understand until I started doing like a deep, emotional dive and excavation on this was like, “Oh shit, the actual argument that we had about the character in the movie, he actually had a valid point.” I just didn’t see it. Then we’d gotten into too much of a dysfunctional place. You’ll see and hear it in real time. I’m interviewing his manager; Leila Steinberg, in Part 1. And I’m also interviewing Tupac’s second manager Atron Gregory. And at one point, the room changed and they put me in that hot seat and are grilling me. That was not planned, but that’s where you’ll hear all about the tussle and what happened. I swear to God, I did not plan this. They really went at me.

DEADLINE: Artists pay a price for their art. Sounds like yours was not only getting the snot knocked out of you, but then having to relive that beating in a documentary of your making?

HUGHES: No doubt. The one thing I need people to understand about this piece is, I didn’t want to do this is because there are rabid fans of Tupac out there, and I didn’t know if I wanted to emotionally re-litigate the past. I didn’t realize that I had a whole bunch of unpacked trauma that I hadn’t even dealt with from that incident. The thing that made it all worth it to me was, I wanted to understand Tupac. I wanted to find the meaning in his journey. I didn’t want it to be just chaos. When I met him, I was completely enthralled by him and I’m like, “Let’s go back to that.” We’ve all heard about the way Tupac tragically died, but what we don’t know was what he was born into. That there was an expectation from the Black Panther Party and his family. They had an expectation. I didn’t know any of that. What does that burden mean? What does that trauma mean?

DEADLINE: What expectation?

HUGHES: They had an expectation that he would be the leader of the new African American Panther party. In Part 1, you hear it mentioned. And at one point he told the manager Atron Gregory, “If you don’t get this deal from me, I’m gonna go be the president of new African American Panthers.” That was really his plan. I bring that up because, I didn’t do this for any other reason than to search for answers. I felt I owed it to the family and the public, even about myself. They’d been disappointed before, and Afeni was disappointed with the depictions, the lack of understanding in the feature film or whatever came out. I really wanted to get this right, and that doesn’t mean do it through rose-colored lenses. It meant, let’s go find the melody in this narrative.

DEADLINE: Why bring this first episode to the Toronto Film Festival, when the series doesn’t air on FX until the winter?

HUGHES: Last time I was here, I got trapped in September 11th. That was From Hell’s press day, that day.

DEADLINE: We discussed that last year as part of the reminiscences of the film crowd that got stranded in Toronto after the planes hit the towers on that tragic day. Did you bring your breakout film Menace II Society there?

HUGHES: We were in Cannes for Menace II Society. Oh, boy, that was something. Here, we were asked by the festival and thought, “This would be great.” I don’t consider any difference between the documentary medium and the narrative feature medium. And when you’re talking about real people and their struggles and journey and all these themes that Tupac’s mother stood for, it felt really important. It puts it in a position to be taken seriously, and not as some fly-by-night sensational true-crime documentary. We all gobble up those docuseries, but this is not that. This is something meant to be taken very seriously. Back when we were accepted to the Cannes Film Festival, I had no idea. I don’t think I even knew what the Cannes festival was when I was 20. And it was an extraordinary validation. Now I know what these extraordinary international film festivals mean, in validating Tupac’s history.

DEADLINE: You’re moving on to another biographical narrative feature on a musical icon with Marvin Gaye. How’s that going?

HUGHES: It’s going well. Like with this one, outside the creative process you’re dealing with variables like estates and music and then things like extended family. Your job becomes a spiritual task to make sure everything is in line. We’ve got all the resources, and we’re close. Frankly, that’s a long-winded way of saying, Mike, that I had to finish Tupac.

DEADLINE: How has this journey helped you grasp Marvin Gaye, who, like Tupac, saw his music reappraised after a death from a gunshot…

HUGHES: There’s a spiritual component to that. And bear with me, cuz it’s gonna take a moment. If you flash back to George Floyd, it felt like 1968 again — the civil unrest and what you would see on the news. And, literally, you would hear in the background “Changes” by Tupac and “What’s Going On” by Marvin Gaye, in the same news story. I walk down the street and I’ve seen murals. There’s one I can think of now on Lower East Side of Manhattan that has Tupac on one side of the mural and Marvin Gaye. I’ve realized through Tupac I’ve started a conversation with Marvin. This washed over me in the most profound way. Creatively, the things you see a bit in Part 1 of Dear Mama, my techniques with these multi tracks and what I can do as far as the sequencing and scoring the movie and decanting this multi-track and finding things in these multi tracks that no one’s ever heard, I found them on Tupac, and I’m finding them on Marvin. Someone said, “Hey Allen, have you gotten stuck in biography land here? “I go, “Well, what about the guys that do Marvel movies all the time?”

DEADLINE: Like the Marvel universe, there’s plenty of connective tissue between these iconic artists who interpreted race relations and turbulence in the moment. Who do you want to play Marvin Gaye?

Mega; AP

HUGHES: I got an idea, but I can’t say it.

DEADLINE: He better be handsome.

HUGHES: Oh my God, he had this ethereal beautiful look. The magic of the What’s Going On album is, some said, it’s just easy listening, but he’s trafficking in such heavy themes. I hate to use the word blessed, but I’m gonna use it here. Blessed when I look at Tupac and Afeni, and blessed when I look at when I’m moving it to next. At least my Marvel universe is riddled with meaning.

Best of Deadline

NFL 2022 Schedule: Primetime TV Games, Thanksgiving Menu, Christmas Tripleheader & More

The Queen Onscreen: 15 Actresses (And Actors) Who've Played Elizabeth II In Film And On TV

'Blonde' Premiere Photo Gallery: Ana de Armas Channels Marilyn Monroe At Venice Film Festival

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.