Alaskans may hold key to health care bill, and they have … issues

ANCHORAGE — After a bruising and tiring fight in D.C. over health care legislation, both of Alaska’s Republican senators returned to the land of the midnight sun to celebrate Independence Day with parades and other activities, including a chainsawing competition.

But the lawmakers are finding that the bill drawn up by the GOP leadership is deeply unpopular with their constituents and with Alaska’s independent governor, Bill Walker, who said it would leave the state “sorely damaged.”

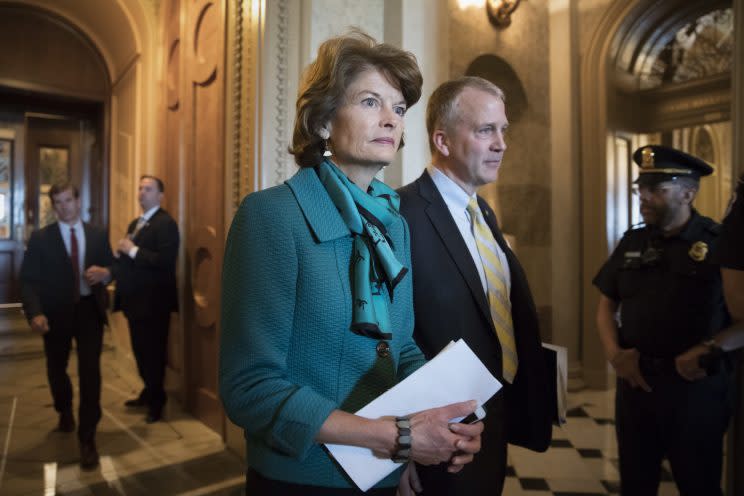

Both of Alaska’s senators have played pivotal roles in the debate and could be deciding votes if the bill finally reaches the Senate floor, giving this often-overlooked state with its unique needs and concerns a disproportionate say in shaping the legislation. Sens. Dan Sullivan and Lisa Murkowski have indicated they were reluctant to support the bill in its current form and praised the decision to hold off on a vote until after the July 4 recess, which ends July 10.

“As we move forward, I will continue to work on the draft of the Senate bill to make it better for Alaskans by continuing to focus on what’s worked under the Affordable Care Act — like continued coverage for those with preexisting conditions — and to replace it with a bill that will better serve our state,” Sullivan said in a statement last week.

Murkowski, speaking to the Washington Post at a holiday event in Wrangell, acknowledged the negative impacts the bill may have on Alaska.

“Most people don’t ask ‘for or against,’ ” she said. “They just say, ‘Make sure you’re taking care of our interests.’ In fairness for those that do the ‘for or against,’ everybody is pretty much [saying] they don’t think this is good for us.”

But while Murkowski and Sullivan were marching in parades, Alaskans expressed concern about cuts to Medicaid and how they would affect children, the elderly and the disabled.

Related slideshow: Protesters across the country oppose GOP’s health care plan >>>

Cutting Medicaid is one of the key pieces of both the Better Care Reconciliation Act, the Senate health care proposal touted by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., and the House-passed American Health Care Act. This could affect the more than 180,000 Alaskans on Medicaid, almost a quarter of the state’s population.

The Senate version would slash Medicaid payments by $3.1 billion over six years, according to a state-commissioned report released last week. The cut is even larger than the one proposed in the AHCA.

The expansion, which Walker pursued in 2015 over the objections of the Republican-controlled state legislature, affected more than 34,000 people who previously lacked coverage. Those people would lose care by 2020, according to the report. The analysis noted that further cuts were possible given the state’s bleak budget outlook, which has been hurt by low energy prices.

Facing a $2.5 billion budget deficit, Walker signed off last week on a spending plan that included almost $16 million in cuts for the state Medicaid program. Advocates are concerned that the state will not have the money to help those who could lose care under either the House or Senate bills.

Dr. Anne Musser, director of the Alaska Family Medicine Residency and a doctor at Providence Health Family Medicine Center in Anchorage, said cutting into the Medicaid expansion would especially hurt many of the children she sees at her clinic. According to a 2015 state report, 57 percent of those on Medicaid are children who take part in the Denali KidCare program, which provides free or low-cost doctor’s visits and screenings for children statewide. Musser said many people don’t realize that Denali KidCare receives Medicaid funding as part of the federal Children’s Health Insurance Program.

“When people talk about Medicaid and people read about Medicaid in the newspaper, they don’t really realize what Medicaid is,” Musser said. “So when people hear about Medicaid and think, ‘That doesn’t affect me,’ they may well be on Denali KidCare and not even put the two together.”

Rolling back Medicaid could overwhelm clinics like Musser’s, or Anchorage’s community health center, as families lose coverage and are no longer able to afford private care.

“More and more private physicians, physicians in smaller practices, won’t be able to sustain taking care of patients,” Musser said. “Even though they are good people and even though they have good hearts and want to provide access to people, they also have to keep their businesses open.”

In most states, patients can go to the next town if they can’t find the care they need nearby, but Alaskans have few options outside of Anchorage, the only big city.

“There are no other places to go here — it’s Anchorage. You don’t get to go to the next nearest city because there isn’t a next nearest city,” she said.

The increase in patient load would compromise the clinic’s ability to provide behavioral and social support to patients, which Musser said is an important function.

“There has to be some sort of social work and behavioral health and all sorts of support mechanisms so the person can stay healthy between doctor visits,” she said. “And Medicaid expansion was allowing us to provide those kinds of services in the community. … They’re going to lose all of the support services in between [those visits].”

Cutbacks in funding for Medicaid would also affect those with disabilities. Alaska has almost entirely switched to home- and community-based care for the disabled.

Harborview Center, a state-run institution for the disabled, was closed in in 1996, something Lizette Stiehr, executive director of the Alaska Association for Developmental Disabilities, said is a point of pride for the state.

“This is something we’re proud of, including in the community this group of people,” Stiehr said.

This system helps patients live in more comfortable settings but also presents a problem, as Medicaid funding for many of these programs is optional.

Stiehr said that if states like Alaska find themselves in a budget crunch, they may be forced to cut funding for optional programs, which could leave the developmentally disabled without services.

“The fear is people fall through the cracks. Do they become homeless? Do they go back home?” she said. “Without this system … what would their options be without a safety net?”

This is also a concern for elderly Alaskans, who often forgo expensive nursing homes in favor of remaining in communities that they’ve been a part of for decades. This has helped keep those towns vibrant but also means that the state has few nursing homes — 18, according to data collected by the Kaiser Family Foundation. By comparison Vermont, a state with a comparable population but an area roughly 69 times smaller, has 37 homes.

Terry Snyder, volunteer president of the state’s AARP chapter, said rolling back Medicaid could endanger the state’s ability to provide home-based care. States, especially those embroiled in financial hardship, could use the additional flexibility in the BRCA to make it harder for home health care providers to get funding.

“We put a lot of energy into home care and keeping them in their own places and letting them age in place,” Snyder said. “We don’t know how that’s going to be affected.”

This concern is particularly sensitive in Alaska, as it has one of the fastest-growing elderly populations in the country. The Kaiser Family Foundation notes that the number of Alaskans age 85 and older is expected to grow by 135 percent by 2030, more than any other state in the nation.

Drawing an analogy to school funding, Snyder said, “We have a robust home-schooling system … but if everyone decided to go into brick-and-mortar schools, we’d have a crisis. So it’s a balance. I don’t know that the state has a backup plan for that if people couldn’t get home care. I think that should be part of the discussion.”

As Murkowski and Sullivan head back to Washington next week to work on changes in the bill, Snyder said Alaskans will be paying attention to their final decision.

“I can hardly go somewhere where people don’t want an update,” she said.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: