Al Pacino, The Oddfather

GET OFF THE elevator on the tenth floor of the Essex House Hotel in New York City, and standing there is a heavyset guy who speaks immediately into a microphone on his lapel. I make him for a fat Secret Service agent and expect that three or four more will soon come peering out of the hallway with their smooth stone faces, and in a suite behind them somewhere will be the candidate himself.

Immediately, I pull out my New York City Police Department working-press card for all to see.

"Who's up here?" I ask.

"Warner Brothers suite," he says.

"Stop it."

"That's what it is. Warner Brothers."

I put the card back in my pocket.

"Do they give you a gun?" I ask him.

"Let me find out where you should go," he says. Into his lapel he speaks, then cocks his head, then says to me, "The press conference is down on the lobby floor. The ballroom."

I go down, slip through gleaming double doors, and join a crowd in deep silence.

In front, behind the altar, is Al Pacino on the left and Robert De Niro on the right.

In the seats, people are filling their notebooks.

I notice a headwaiter. I whisper, "What is this?"

"Foreign press," he says.

"For what, a treaty signing?"

"Warners got two floors of press put up here. They get anything they want. You want anything?"

"Yeah, get me a steak, right now."

Before I can stop him, he's telling a white-coated waiter what to do, and then that guy is gone. But this is no time to eat. This is a press conference.

"Mr. Pacino," somebody asks, "what do you think Mr. De Niro's greatest works are?"

"Some of his greatest work," Pacino says, looking at De Niro. "I can remember, ah, Raging Bull, and then his subtlety in Once Upon a Time in America. His Godfather II."

"And Mr. De Niro, what do you recall?"

"All three Godfathers. Great."

While they run this interrogation, my mind begins to wander, and I find myself considering how much of what we know about Mafia killers we learned from these two actors. And then I am thinking of real Mafia killers, and of Jo Jo from the Gotti gang, who one February was going to gain control over all the corned beef in New York so that when the Irish started preparing for Saint Patrick's Day, Jo Jo would have the market cornered. "I will be a rich man off those effin' Irish," he told himself.

I say aloud, to myself, "That effin' Jo Jo was a moron."

Now a young woman looks over at me. She gets up and whispers to another young woman. Then she walks over.

"Did you say something?"

"No. I just said that Jo Jo is an effin' moron."

"Ah. Who are you?" she asks.

"I'm here to watch this thing."

"I'm sorry, but this is a private press conference for international press only."

Reluctantly, I confess that I am supposed to be here.

"Oh," she says, "you're here for City Hall. That movie doesn't open until February. This press conference is for Heat."

"But I just ordered a steak," I say.

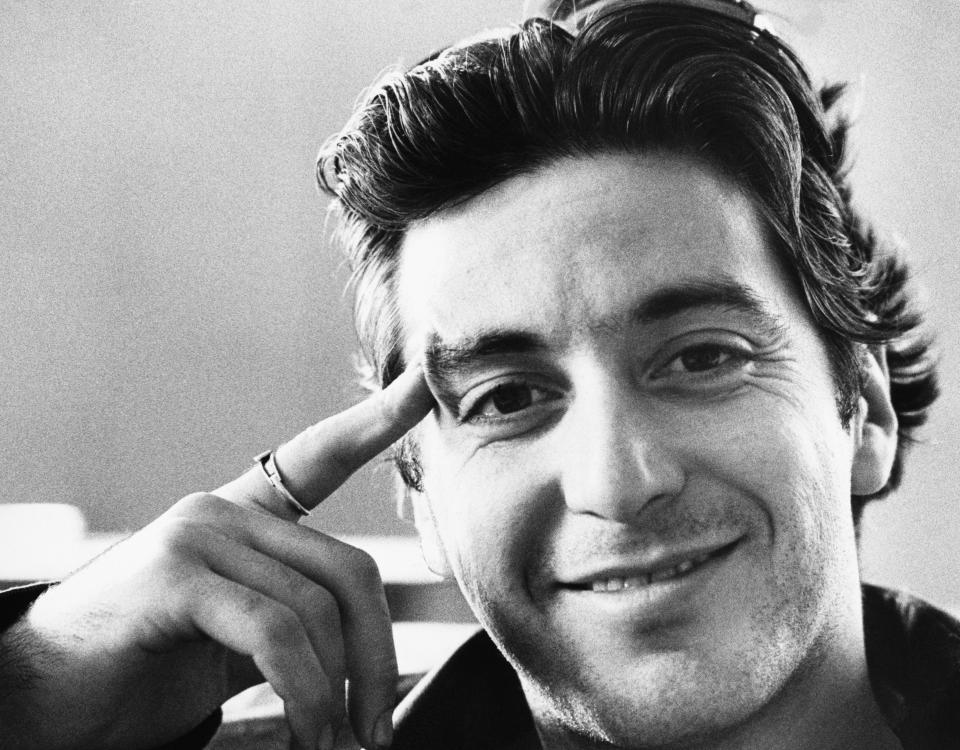

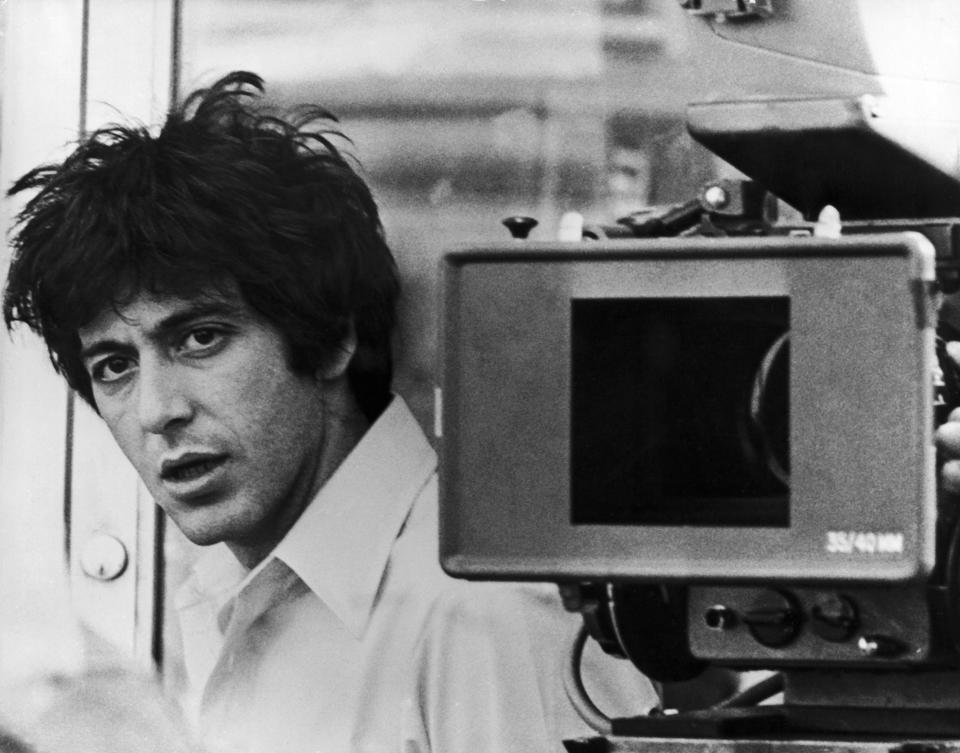

AL PACINO IS FAMOUS mostly because of his extreme, unique, and undeniable talents as an actor and movie star during the past twenty-five of his fifty-five years. But he is also well-known for being hard to figure, which comes out in several ways. He is reluctant to talk to reporters, for example. But there are times when to do so is absolutely necessary, as when a movie of which he is the star, such as the forthcoming City Hall, is about to open. (In it, he plays the Greek American mayor of New York City, and since no one has ever paid me to critique films or anything else, let's keep my record clean.)

The truth of the matter is that whenever the release of a new Al Pacino picture dictates that he must talk to the press, he does so, but he rarely has a great deal to say about the movie he's in-you practically have to drag it out of him. About City Hall, all he really had to say was that his character was modeled on New York City's late, famously bighearted congressman Vito Marcantonio, the East Harlem communist.

"That's who I played. I know him. I feel him."

"Did you see him much when you were growing up?"

"I never saw him."

What Pacino will always talk about, what he has discussed easily and endlessly with every reporter he meets, what he returns to with passion and conviction, are two films definitely not destined to add fame or fortune to his name.

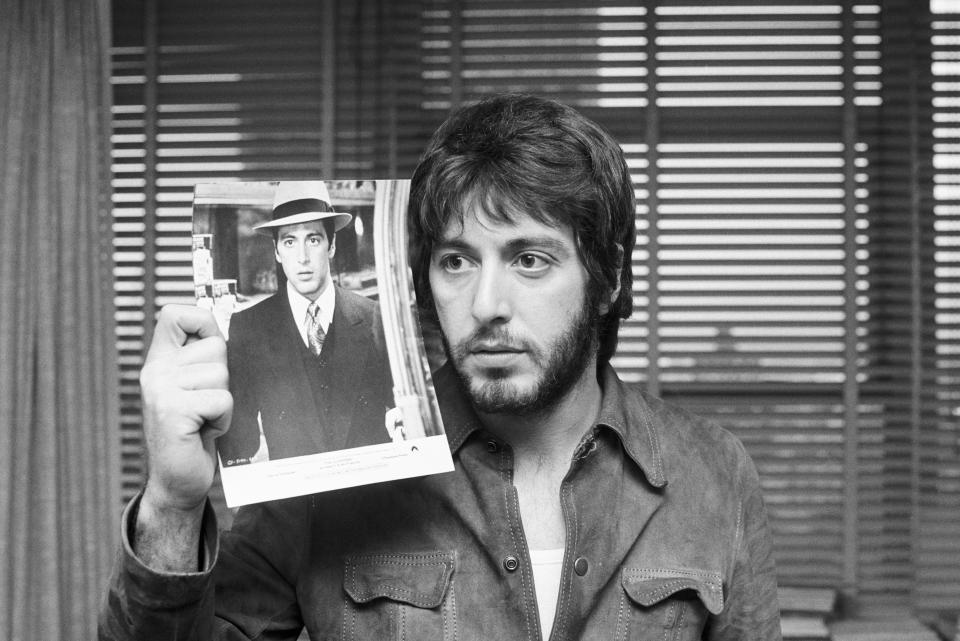

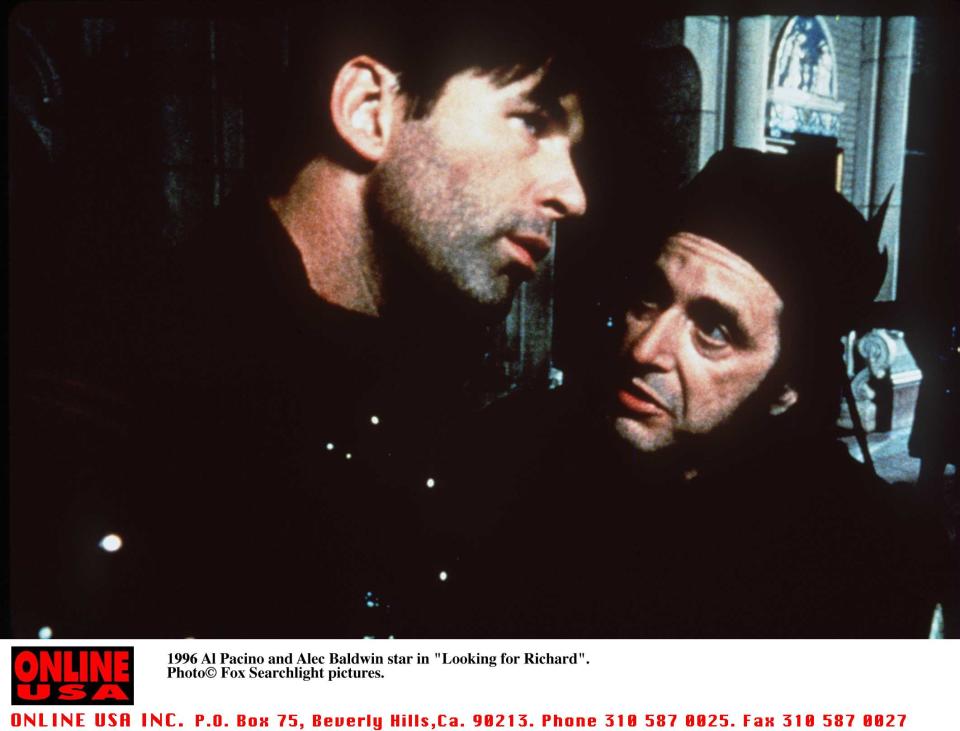

One of these is called Looking for Richard and is based on Shakespeare's Richard III. It is a project that Pacino has been making with his own money, his own time, and his own artistic visions. It is half documentary, half performance of the play, and Pacino is the producer, director, and star. He shot about eighty hours of film and edited it down to around two hours. He has been at it on and off for four years now.

In fact, Pacino is at this very moment wearing a crown and a beard, and his mouth is twisted in agony as he fights with a sword. His steed runs away to the top of a hill. Al screams from the pit of his stomach, "My horse!"

We are in a studio on Broadway, and in the room are a technician and ten actors sitting along the walls, there to dub their voices. In a room outside are three or four more technicians, all there for Pacino, which is how he likes it.

The place is getting crowded, so I go into another room and sit on a couch. A second later, somebody comes in and puts a tape in the machine, saying, "You can watch it right here and be more comfortable."

Onto the television comes Pacino again with the beard and the crown and the horse and the yell.

Only a few minutes pass before somebody comes in and says, "Well, what do you think?"

"I have to see it all before I can say," I reply.

Unlike Pacino, I am not famous for my devotion to Shakespeare. And at this point I have yet to see his other personal project, an even stranger film to which he is even more seriously committed. In 1968, when he was still a talented nobody, Pacino performed in a play called The Local Stigmatic. It had been written three years before by a raging young English playwright named Heathcote Williams and deals with two lower-class cockneys and an upper-class character whom they more or less terrorize. Pacino loved the play from the start, and his feelings for it did not diminish over the years. In 1985, he put up money to film the play, starring himself. In the decade since, Pacino has regularly screened, edited, rescreened, reedited, thought about, and talked about this movie to anyone who would listen. He has done everything with it except release it or earn back a nickel of what he's put into it.

There is no other recorded case like this in the history of American movie stars. Sure, some big movie actor or actress will occasionally find a spare week or two to throw to Shakespeare, or some brilliant, starving young playwright, or some struggling new director with a small art-house movie. But no movie star has ever created his own work of artistic obsession, let alone two of them. Only this guy.

"I played Michael in The Godfather and I'm Michael forever."

I asked him, "Do you make these art movies as a reaction to all the rat gangsters you play?"

"You could say that doing them is therapy," he said.

"What do you need that for?"

"I feel disenfranchised sometimes."

"Why do you think people love gangsters so much?"

"My daughter was in the car with me," he said, "and I asked her why Santa Claus is fat. And she said, 'People want him to be fat.'"

"People like gangsters?"

"Sure. They're outside. They're anarchic."

"Do you like playing them?"

"Do I?"

Electricity went through his body when he said it.

His voice raised, and he said, "In Scarface, and I love that movie, a guy with a chain saw is about to cut into me...."

Then he called out his line from the movie:

"Why don't you try sticking your head up your ass and see if it fits!"

"What other lines have you liked saying?"

He called out to the room:

"I'll make him an offer he can't refuse."

Everybody laughed.

"That's what I am, I guess," he said. "I played Michael in The Godfather and I'm Michael forever."

"Does that bother you?"

"No."

But then why does he bother doing these art movies that eat up millions of his dollars and years of his life? Is it some need to stay connected to his early days as a performer, back in the sixties, when the work was what counted and there was no fame or money in it no matter how well you did it?

"I was used to working on a tightrope onstage," he says of his youth in the theater. "A movie is just a line painted on the floor."

"OH, I KNOW he came from around here, and he was very tough," Alejandro Stevenson, fifty-five, was saying. He was in the shop next to the old Dover Theater, which now is the Iglesia Pentecostal Jehova Shalom, a place of worship in the South Bronx, Pacino's old neighborhood.

"How do you know he was so tough?"

"Everybody knows he's very tough. When he was stuck in the doorway and the policeman shot him in the face."

"When was this?"

Without looking up from her magazine,

Wanda Diaz, who was sitting behind the counter, said, "Serpico."

"But he learned that here," Alejandro said.

"He was very tough here."

He's not even close. Pacino's father split when he was a baby, and his mother was ill, so he was raised mainly by his Sicilian grandparents. If you want anything stricter, try a convent. He lived on the top floor of a building in the South Bronx and the other kids called up to him from the street. Put a hand on that doorknob, his grandmother's look said, and I will teach you pain. He stayed home and read books.

He became famous for killing, but he learned it inside the Dover, not outside in the Bronx.

The Dover Theater was where he took his first acting lessons, sitting next to his grandmother, watching James Cagney with guns blazing, or Ray Milland's frantic search for the bottle in The Lost Weekend. Little Alfredo walked out of the Dover with his hands waving and his big eyes searching the sidewalk for a bottle. The grandmother loved it. When he was visiting his father in East Harlem, the father said, "Do the bottle," and five-year-old Al was like a midget Ray Milland. The men on the sidewalk laughed and were delighted.

Years later, he became famous for killing, but he learned it inside the Dover, not outside in the Bronx. Look at the three men responsible for most of what we know of the mean violence of city streets. Director Martin Scorsese had asthma when he was a kid and spent hours looking down at the street outside his bedroom window. Robert De Niro's father was a gentle, talented artist. And Pacino was under the hawkeye of a protective grandmother. Among the three of them, they don't have an arrest for littering.

While still in his teens, Pacino became one of the ragamuffins loitering outside the HB Studio on Bank Street in Greenwich Village, waiting for acting class to start. His teacher was Charlie Laughton, an actor and a poet. What Pacino learned best from Laughton was how to be broke. The first time the two ever spoke, Laughton walked up to Pacino and said, "Do you have a dollar? I need carfare to get home."

Pacino was shocked and deeply disappointed that the teacher, the man he looked up to, was a busted valise. But he came out with his bankroll, two single dollar bills.

He gave one to Laughton and kept the other.

There was also a day in 1959, when Pacino was nineteen and broke as a hobo, that tells what those times were like. It was August, and everybody heading to Rockaway Beach on the A train was wearing light, summery clothes. Everybody except Pacino, who owned only black, including black work shoes. He came out from under the boardwalk onto the brilliant white-sand beach and trudged along, looking for Laughton, who had somehow managed to rent a bungalow for himself and his wife and baby.

If Pacino's plan worked out, he would find Laughton on the beach and borrow five dollars from him so he could eat. If Laughton had no money to spare, a good possibility, Pacino would still have enough to return home, though not enough for a meal. Pacino found Laughton on the sand with his wife and baby and asked for the five. Laughton had to look, but then he came up with the five dollars, and Pacino ate that day, though he had to wait until he got back to Manhattan because the prices by the beach were too steep.

"There is a certain freedom to being broke," Charlie Laughton says today. "We would walk from Brooklyn to Manhattan and stop at McSorley's Ale House and sit as long as we wanted over a drink. There was no real responsibility in the morning, so we could stay out as long as we felt like."

Pacino was not earning enough to allow him to look a landlord in the eye. Lucky for him, he had an actress girlfriend named Jill Clayburgh, and she had a father who sent a couple hundred every month, enough to allow them to live. She also had a job, a role on Search for Tomorrow, a soap opera.

"I never saw her on the show once," Pacino says, "but I helped her rehearse her lines. That was worth something, wasn't it? And when I came home at four in the morning, I was very quiet so I wouldn't wake her up. She had to be at the show early."

Pacino found work here and there, in lofts and coffeehouses and workshops. In a play called The Indian Wants the Bronx, he was spotted by Faye Dunaway, who told her manager, a man named Marty Bregman, to witness Pacino in action. In a play called Does a Tiger Wear a Necktie?, Pacino was seen by a movie producer named Dominick Dunne, who was looking for an actor for the lead in a movie called Panic in Needle Park, which had been written by Dunne's brother John Gregory and sister-in-law Joan Didion. The combined forces of Bregman, who's now a big film producer, and Dunne, who's now a famous author, got Pacino the part, his first starring role in a movie. When it came out, his performance was reviewed as an "exceptionally successful starring debut."

"TAKE THE ORANGE out and put in the blue," one of the editors said. "To do that, I have to go from orange to black-and-white and then put the blue in," another one of them said.

They were editing color on Richard. Pacino, watching the tape, said, "The blue is cooler for the internal nightmarish scene."

One film editor said, "It's warmer inside the tent. Orange, yellowish."

"Yes," Pacino said. "Take the orange out and put in the blue. Let's see if we can do it after Sundance."

He was very excited. They were going to work all night. They were going to show the film at the Sundance Film Festival. And the Fox movie people had put up some money to have the film ready for the showing.

After Needle Park, Pacino made the movies that made him a legend-The Godfather, Serpico, and Dog Day Afternoon-one right after the other. After that, he passed on some roles people think he should have taken, and took some roles people think he should have passed on. Whether those people are right or wrong, the fact is that Pacino is one of the rare figures we call stars who have managed to remain shiny for a quarter of a century. But between the absolute low point of Revolution in 1983 and the comeback of Sea of Love in 1989, he stepped back from the business. He stepped back and went to where he has always felt at home-three flights up in a drafty place where they can put down enough chairs to call it a theater. He pulled out a copy of his greatest puppy love, The Local Stigmatic, and began work. He had lost nothing that he had to go back for, but he wanted The Local Stigmatic so much that he went for about a million dollars, personal money. He worked through long days editing the film down to fifty-four minutes. He invited people to watch. Sometimes, he required them to watch it. Some he might even have begged to watch it.

"Al called from Paris last night to ask if you were coming," Pacino's right-hand man, Michael Hadge, said. "He was so happy when I told him you said you'd come." This was in a screening room on the fifth floor of the Brill Building on Broadway. "We're waiting for Mia Farrow," Hadge said.

Now Mia Farrow came off the elevator in a cap, round glasses, a storm coat, and farm-girl pants and boots. She smiled and we went in and sat down.

Up on the screen was Pacino with a cockney accent. Brilliant one, too. He was talking to another guy. The other guy had nothing to say. And so it went. Talking. A play on film. I didn't know what it was about. When it ended, I was off the seat and out of the room in one motion.

While I was waiting for the elevator, Mia Farrow came out. She was smiling and speaking to someone still in the room. "Thank you very much. Tell Al thank you."

"Did you like it?" the guy asked her.

"Oh, yes. Very much."

The guy was elated.

Then the elevator came and we got on. She smiled.

"What did you think?" she said.

"Not very much. Did you like it?" I asked her.

"No, it was boring," she said.

"So I'm not alone."

"What are you going to say to Al if you see him?"

"I'm going to say, 'Give me an effin' break, will you, Al?'"

As we walked up Broadway together, she said, "I have a movie out." She shook her head.

"What's the matter?"

"The studio went belly-up. They can't even take out an ad to say where it's playing."

"I'll look for it."

"That would be nice."

Already I don't remember the name of the picture, or anything else about it, but if I ever see her again, I'll say, "Oh, yes. I liked it very much."

Pacino never discusses his personal life, especially not his love life, which means he probably has hundreds of women, because the ones who brag are usually all talk, and vice versa.

IN HIS OFFICE IN an apartment building on the West Side of Manhattan were crowded two young dogs, a young woman who was minding Pacino's young daughter, and another young woman, who is Pacino's girlfriend. Pacino never discusses his personal life, especially not his love life, which means he probably has hundreds of women, because the ones who brag are usually all talk, and vice versa. He's never been married. His daughter came about from a romance that didn't go too far.

Also in this office were a guy making coffee in a small kitchen, two people in another room, and three in yet another, a small, narrow one that had six video screens of various sizes showing Looking for Richard.

Pacino was there, too. His dark hair was standing up. It was obvious he was having a problem.

"You see why you should make movies with your own money?" he said. "You have freedom. If I want to work on something for a year and a half, I can do it. But then I take their money and now what do I have? They rush me."

This is a movie he's been working on for four years.

He shook his head. "They want to know when I'll finish the picture. I've only seen it on video. I haven't even seen it on 35mm. How do I know? This is Shakespeare."

On a table was a paperback book, the true story of an FBI agent who took a fake name and became a member of the Bonanno Mafia family in Brooklyn. Pacino rifled through the pages until he came to the pictures.

"Here is my next part," he said. He pointed to a picture of one Lefty Ruggiero.

Right away I thought, Is this guy nuts?

Ruggiero was known as Lefty Guns and he had an IQ of 47. The last time I saw him, he was in federal court in Manhattan, glowing with pride as they played a tape of him saying that he was going to get his machine gun and kill his own gang, every one of them. When the tape ended, Lefty sat in that courtroom and preened.

One of Lefty's associates stepped outside the courtroom and rested his head against the wall. "Did you ever hear anything like that?" he said. "How did I get in with an imbecile like this? They shouldn't allow morons like him into crime."

This is the kind of bum Pacino is going to play next.

"The guy's name isn't worth remembering," I said.

But Pacino said that there was something in the guy that he liked, that he was funny, that his view on life was basic and clear, and that Rick Nicita, Pacino's agent, and Mike Newell, the movie director, had told him that this was a good part for him.

In the other room they were still editing Looking for Richard, which, after The Local Stigmatic, is Al Pacino's true love. He has a ton of his own money in each. A lot of his time, too. Taste does not come fast or cheap.

You Might Also Like