Aimee Mann on the Music That Made Her

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Aimee Mann is tugging at her dummy’s broken mouthpiece. Sitting on a red couch in her L.A. home, she explains how the monocled Charlie McCarthy doll, fashioned after ventriloquist Edgar Bergen’s puppet, became more famous than its owner in the 1930s. “I had two at one point,” Mann admits with a laugh, wearing a plain blue T-shirt and her trademark, thick-rimmed eyeglasses. She’s completely mindful of how creepy Charlie looks with his mouth slack-jawed open as she moves it out of the frame of our Zoom call. “I’m the person who sees it at a flea market and I have to buy it.”

An eccentric artifact with its own complicated relationship to celebrity, Charlie McCarthy sounds ripped from the lyrics to one of Mann’s songs. Her refined guitar pop is filled with attuned details and characters more often associated with the best short stories, as Mann applies her sharp wit to cut to the core of issues like depression, love, and disappointment. She’s so good at bringing underdogs to life in her work, in part, because she’s had so much practice punching up throughout her career: Mann has fought hard to chart her own course in the music industry over nearly 40 years, having endured several label misfires that informed her defiantly independent approach.

Raised in Richmond, Virginia, Mann was exposed to storytelling music early on as she listened to country crooner Glen Campbell’s ambling 1969 hit “Galveston” around the house. She went on to study voice and bass at Berklee College of Music in Boston and fronted an art-punk trio called the Young Snakes. They were a prelude to ’Til Tuesday, the sleek synthpop group she formed in 1983, whose aching ballad “Voices Carry” became an MTV staple and Top 10 hit two years later. The millions-selling single was one of the first songs Mann ever wrote on her own.

’Til Tuesday released three albums on Epic Records, home to decade-defining stars including Michael Jackson and Cyndi Lauper, but broke up in 1989 under pressure from the label to make another smash. From there, Mann began to work on her own solo material, crafting intricate songs that slyly indict the record industry; even today, it can be difficult to parse which of her lyrics are jabs at exes or label suits.

With 1999’s Bachelor No. 2 or, the Last Remains of the Dodo, which is celebrating its 20th anniversary with a deluxe reissue this week, Mann took full command of her output and co-founded SuperEgo Records, an avenue that has allowed her to explore ideas including a boxing-inspired concept album, a wry Christmas collection, and her latest, 2017’s Mental Illness, a canny collection of spare acoustic songs that netted her a Grammy for Best Folk Album.

Mann, who turned 60 this year (a friend gave her a gluten-free cupcake from a safe, six-foot distance), is dryly funny and perceptive while discussing the music that shaped her life. She also continues to side-eye the music industry at large in no uncertain terms: “Obviously every system is garbage, because people are terrible,” she sighs at one point, before breaking into conspiratorial laughter. Yet her unabashed love of music—especially classic folk harmonies, acoustic guitar, and the work of her husband, singer-songwriter Michael Penn—still nourishes her soul. “When I hear a thing that gets me emotionally, I will listen to it over and over and over,” she says. “If you add up all these songs and cram them together, it’s like, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s what I sound like.’”

The Beatles: “Ticket to Ride”

Aimee Mann: I saw the movie Help! and really loved “Ticket to Ride.” The story is: She’s out of here, and he’s on his own and not really sure what went wrong. As a kid watching the movie, though, I saw the Beatles at the ski resort just dicking around and thought the song meant she’s got a ticket to the ski lift and then she’s gonna go scheme. I thought that was what the problem was. But I could tell somebody was really sad. And I was like, “This is for me.”

Elton John: Madman Across the Water

Madman Across the Water was the first record I ever bought myself. I saved up my allowance and went into the record store, and that was on display. I’d never heard of Elton John, but I loved that record cover. It’s so ’70s, with the embroidery and the jeans. That record hit it out of the park so hard that I was forever locked into this idea about album artwork as another way to transmit the vibe of the artist. All through my career I’ve had to push back on this idea that album art doesn’t really matter.

Madman Across the Water is still one of my favorite records of all time. “Tiny Dancer” is just killer. There’s something about certain artists who have a sense of melody and harmony that’s really dead-on. And certain singers just sound like they’re in pain. John Lennon had that, too, where you can hear it in his voice, like, “Man, what happened to that guy?” That quality to the voice really resonated for me.

Steely Dan: Can’t Buy a Thrill

I’ve listened to Can’t Buy a Thrill a thousand times. It’s just a perfect record. Steely Dan have very complicated chord changes, it’s very modal. They also have a really harmonic sensibility that’s not like anybody else’s. The music breaks for long, long solos—and I hate jamming, I hate solos. But I guess making people play 20 solos and then putting them together really pays off, because all of them feel like melodic parts of the song. And there’s something to their music where you can tell that those guys are assholes, but they also sound like they fucked up in a way that feels familiar.

Elvis Costello & the Attractions: “Girls Talk”

I had taken a trip to London with my boyfriend when I was in ’Til Tuesday, and “Voices Carry” was on the radio when we passed Elvis Costello and his wife on the street. My boyfriend said, “We just passed Elvis,” and I’m like, “Who?” He said, “Elvis! We should go back and say hi. I think he recognized you.” I didn’t know anybody named Elvis. I was like, “What are you talking about?” And that’s how I met Elvis Costello.

It was the biggest fucking thrill of my life—what a stroke of luck. He was so nice. He’s the guy who knows everything. His knowledge is deep and vast. It’s really intimidating. We ended up writing a couple songs together, and I used to cover “Girls Talk” live for a while. I was so crazy about that song.

They Might Be Giants: “Don’t Let’s Start”

At this point, ’Til Tuesday went on our first real tour, which was opening for Hall & Oates. We had played up and down New England in clubs and stuff, but to go from some little bar in Franklin, Massachusetts, where people are spilling beer all over the place to an arena opening for this major act was really incredible, but also super daunting. Once you’re touring, you’re not hanging out with your group of friends, and your relationships all become distant and fractured. You’re just in a van on the road in the middle of nowhere for a couple of years. So I didn’t really listen to music. The only music I heard other than our own was Hall & Oates’ set every night.

But in 1985, somebody gave me a Sony Walkman, and I was like, “Oh my god, this is amazing.” They Might Be Giants was one of the bands that had started up that I really liked: super goofball, but with these deceptive pockets of melody and interesting lyrics. “Don’t Let’s Start” is very angular, but he’s also singing, “Don’t, don’t, don’t let’s start/This is the worst part.” Melodically it’s really pretty and accomplished. The goofiness is more like an overlay. They’re very inventive.

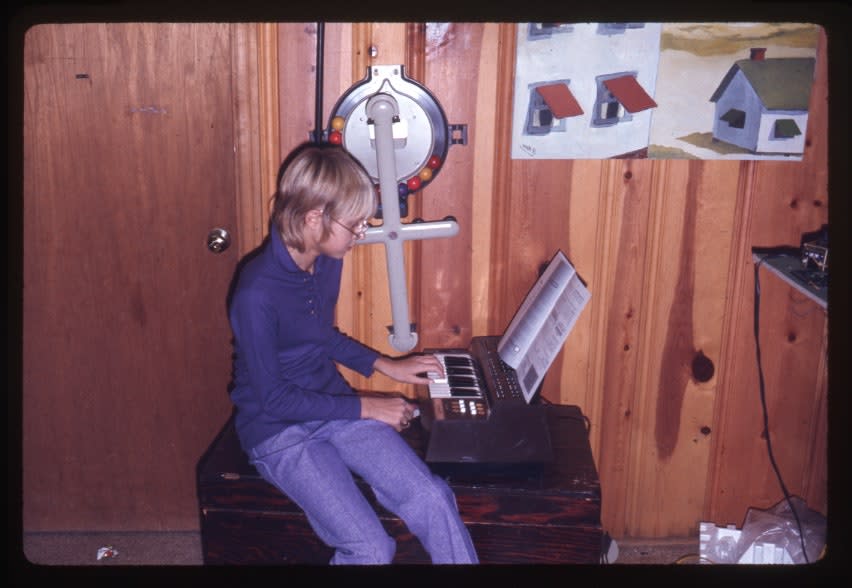

Photo of Til Tuesday

Michael Penn: “No Myth”

By 1990, everything on the radio was starting to be Whitney Houston, Taylor Dayne, Tina Turner—it was very pop. Then Michael Penn comes out with this Beatles-esque, melodic song, but still with a little bit of a big snare drum sound. I was like, “Finally, somebody broke through with an actual song.” It was on that tour [around Penn’s album, March] when I met Michael for the first time, and then we vaguely kept in touch. We got together years later. I love “No Myth.” And that record is fantastic from beginning to end. You may think I’m saying this because I’m a nice person who is supportive of their spouse. That’s absolutely not true. I’m not that supportive.

AIMEE MANN

The Loud Family: “Inverness”

In the early ’90s, I started listening to a lot of older bands: the Kinks, Zombies, Squeeze, all the older Britpop stuff. Anything that had a Mellotron and 12-string electric guitar. All of that came out on my album Whatever.

I was also listening to the Loud Family’s [1993 debut] Plants and Birds and Rocks and Things, which is one of the best records. I really had trouble moving on to any other Loud Family record—I just wanted this one to keep going. I don’t think I can listen to it anymore; after [frontman Scott Miller’s] suicide, it’s fucking rough. But “Inverness” is one of my favorite songs. I love his super weird singing style. I met him later, and he couldn’t be a nicer guy. This was another song I would play live sometimes, and I played it with Scott at a show of his. [sings] “I bet you’ve never actually seen a person die of loneliness.” Very COVID-appropriate.

Elliott Smith: “Waltz #1”

I listened to Elliott Smith and Either/Or a lot. Sort of like Liz Phair, Elliott Smith was inspiring in that he reminded you that you can write a song about anything you want to. You don’t have to feel like, “Oh, that’s too personal or too weird or too dark.” For me, as a listener, it’s helpful to hear people be honest about their very personal struggles.

Michael Penn: “Walter Reed”

I think this is a perfect song. To me, this sounds like if the Beatles were Jewish, because [Penn] is half Jewish, and there’s a cadence that’s a little Eastern European with the way he uses dominant sevenths. “I’m ranting while I’m raving/There’s nothing here worth saving”—that’s a brutal lyric. He’s really a top-rated songwriter for me, and thank god, because how sad is it if you were with another singer-songwriter and you’re like, “Yeah, whatever, it’s not my kind of thing”?

It’s sad that people like him slip through the cracks. There are the showboaty, “look at me, I will do anything for attention” people, and then there are some people that are just very shy, and it’s really difficult. I wish there were a better way for us to support artists like that.

Shortlist Awards

Sharon Van Etten: “Peace Signs”

There is something very, very raw about this song, which I really appreciate. As time goes on, the music that rises to the top is the music that labels put a lot of money behind, and they’re not gonna put any money behind something that is not going to be a blockbuster; it’s never the shy, interesting person who’s a clever songwriter. So it’s nice to hear somebody who was just using an electric guitar and singing. She sounds so much like herself. I want people to sound like themselves. I don’t want them to sound like other people that you’ve already heard. I want it to be revealing and personal.

Bread: “Everything I Own”

When Ted Leo and I were on tour, we listened to a lot of Thin Lizzy, which was a real inspiration for the Both, our group together. But we also started listening to Bread—I think at first as a joke. Even in the ’70s, when they were timely, Bread was pretty uncool. But I was really curious to listen back to that now that the time for cool or not cool is over for me. It was to hear the musicianship, but also to sometimes still go, like, “Yeah, that’s still an objectively terrible lyric.” But [Bread singer David Gates’] voice is like a miracle. He’s incredibly good. I was just really in the mood for something soft. That inspired my last record, Mental Illness, in that I just made a decision to be like, “This is what I’m in the mood for. I’m going to keep it as stripped down and soft as I feel like.”

Frank Sinatra & Antônio Carlos Jobim: Francis Albert Sinatra & Antônio Carlos Jobim

I discovered this record in 1980 when I worked in a music store. It was this big kind of Tower Records in Boston with three stories, and I was working in the pop department, and it was driving me crazy. So I asked to work in the middle floors with the classical vocal stuff—nobody ever went there. You could take records out and play them, so I would sometimes play classical music, or this barbershop a cappella group called the Hi-Lo’s, who had these really crazy arrangements. And then I played this record of Sinatra and Jobim playing bossa nova... oh my god, I fucking love this record. I listened to it a million times back then, and I’ve been listening to it recently because it just helps calm me down.

Originally Appeared on Pitchfork