Ailing ‘Superman’ Star Valerie Perrine Finally Finds Her Hero: “The Guy Should Be Sainted”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Valerie Perrine has a knack for cheating death.

At 25, Perrine — best known for playing Miss Teschmacher, girlfriend to Gene Hackman’s Lex Luthor in 1978’s Superman — was working in Las Vegas as a topless dancer in the Lido de Paris revue at the Stardust Hotel.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

She met a charming guy in the lounge who said he was a hairstylist to the stars. They began dating. He invited Perrine to an intimate dinner party in L.A.’s Benedict Canyon. She found an understudy, but the understudy fell ill, and Perrine was forced to perform.

The party she missed would go down in infamy: It was the one in which the Manson Family slaughtered six people, including Sharon Tate and Jay Sebring — Perrine’s new hairstylist boyfriend.

Then, when she was 32, having shot to movie stardom as a thinking-woman’s bombshell, she boarded a small plane to the San Sebastian Film Festival.

She was headed there to support Bob Fosse’s Lenny, in which she played Lenny Bruce’s stripper wife, Honey Bruce, a performance that earned Perrine awards at Cannes and BAFTA and a best actress Oscar nomination.

The plane crashed upon takeoff from the tiny airport in the Pyrenees, losing a wing and its landing gear in the process. Miraculously, she walked away from the wreckage with only minor cuts and bruises. She even returned to the wreck to retrieve her makeup kit.

Now 79, Perrine is still cheating death. The actress has been quietly waging a valiant battle against Parkinson’s for a decade.

It has been a long, trying road. The disease has robbed Perrine of her mobility and much of her ability to eat and speak. But she’s still here — still smiling, still joking, still puffing on a pot pen.

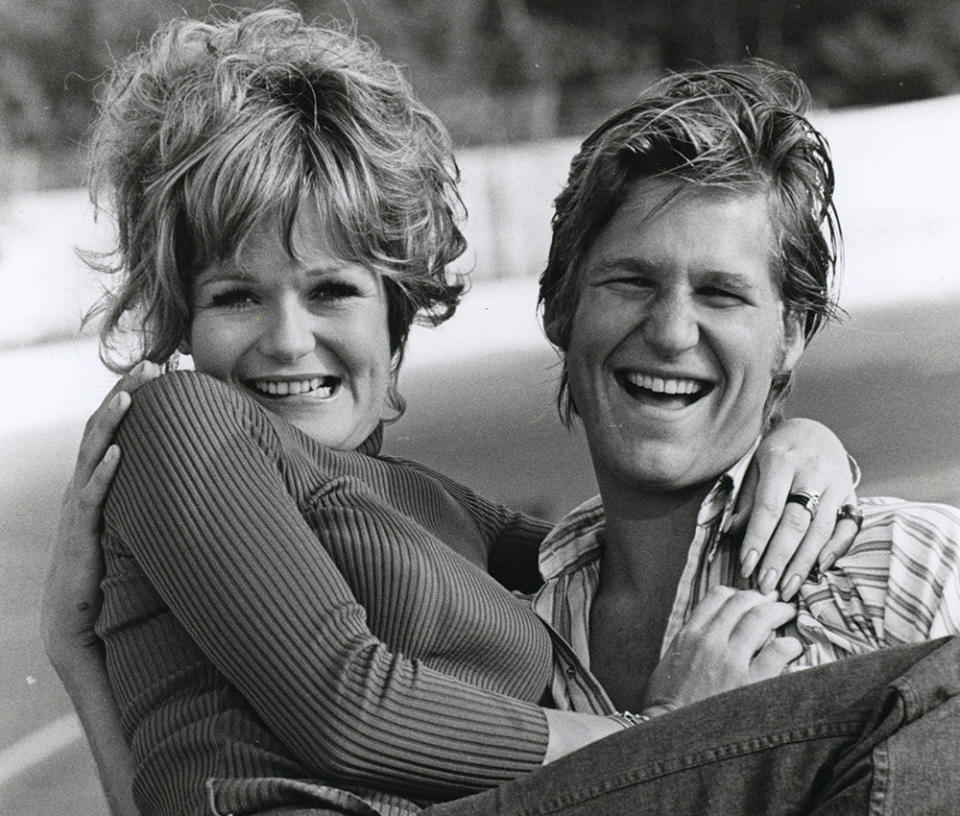

Perrine insists she wants no pity and regrets nothing about her Technicolor life: not one affair (she’s been romantically linked to everyone from Jeff Bridges to Elliott Gould to Dodi Fayed); not one hit of acid (she’s taken LSD more than 400 times, by her estimation); not one career move (well, she probably should have said yes to 1981’s Body Heat and no to 1980’s Can’t Stop the Music, the Village People-starring megaflop she says killed her career, but you can’t win them all).

Perrine has lived in the same Beverly Hills apartment for 13 years. She occupies a “Victorian-like room,” says her younger brother, New York City-based neuropsychologist Kenneth Perrine, 70. “There’s not a square inch of table space that’s not covered with something — with a picture, a jewelry box, some marker of her past. That room, to her, is her life.”

Never very far away are her two constant companions: Marcus, the Chihuahua-Yorkie mix she bought from a perfume counter girl one Christmas at Neiman Marcus, and Stacey Souther, Perrine’s Rock of Gibraltar.

They are an unlikely duo. With a chiseled jaw and Southern ease, Souther, 50, journeyed from Georgia to Hollywood during the early 2000s with dreams of becoming a movie star. Instead, he met Perrine. They’ve been inseparable — and, both insist, completely platonic — ever since.

Souther transports Perrine to every doctor appointment. He makes sure, along with the help of a caregiver, that Perrine is fed, happy and comfortable. They watch movies together in the evenings, after which Souther will frequently spend the night on an inflatable mattress spread out across the floor. For this, he accepts no payment.

“I’m sure people are like, ‘Why does he do it?’ ” Souther says. “It’s weird to hear the question to me because I’m like, ‘Why wouldn’t you do it?’ ” Valerie’s brother puts it another way: “Why is he doing it? Pure altruism. The guy should be sainted.”

***

In 1946, when Perrine was 3, her father, a lieutenant colonel in the Army, moved Valerie and her showgirl mother to a station in postwar Japan.

At 4, Perrine discovered her love of the spotlight, performing Japanese ceremonial dances with a local troupe. “For the finale, they would remove my wig and I would come out dancing with blond hair tumbling down my back,” she once wrote in notes for a future autobiography. “The crowds would go crazy and rush the stage, put me on their shoulders and parade me through the streets. The emperor of Japan traveled 400 miles to see me dance.”

By 1950, the family had relocated to Phoenix, and her father, who struggled to find a civilian career, started drinking heavily.

“Daddy lost money,” Perrine tells me. So at 17, she took off for Las Vegas to try to make it as a showgirl. “I wanted to show off,” she says. She literally knocked on doors up and down the Strip until she scored her first break — as a chorus girl in the Hello America show at the Desert Inn Hotel and Casino.

Between performances, management would send her onto the casino floor, where she’d cozy up to high rollers who’d toss her a chip or two. Later, she negotiated a starring role in Lido de Paris, which required her to go topless in belle epoque gowns and gargantuan headpieces.

Before long, Perrine was earning $800 a week — the equivalent of $8,000 today — and was sending money back to her parents in Arizona.

“It was great,” she says.

“Was there a lot of temptation there?” I ask.

“I wasn’t tempted by what was available,” she replies.

The truth was, Perrine had already found the love of her life. His name was Bill Haarman, and he was a successful importer and gun collector who lived in Beverly Hills.

The handsome Haarman, then 30, proposed to Perrine, and she accepted. But in January 1969, one month before the wedding, the Walther P39 tucked in his waistband tumbled to the floor and fired a bullet, which ricocheted off a door and into his heart, killing him instantly. Perrine never recovered.

In August, Sebring, her rebound fling, was shot and stabbed to death by Charles “Tex” Watson at Tate’s house.

“If you don’t like somebody, fix them up with Valerie and he’ll be dead within three months,” cracked one of the male singers at the now-demolished Stardust.

Though she romanced many over the years — including Fayed, who died in a car crash alongside Princess Diana under Paris’ Pont de l’Alma — she never married. Instead, she surrounded herself with dogs, the bigger the better: four Great Danes and a mastiff who weighed 250 pounds.

***

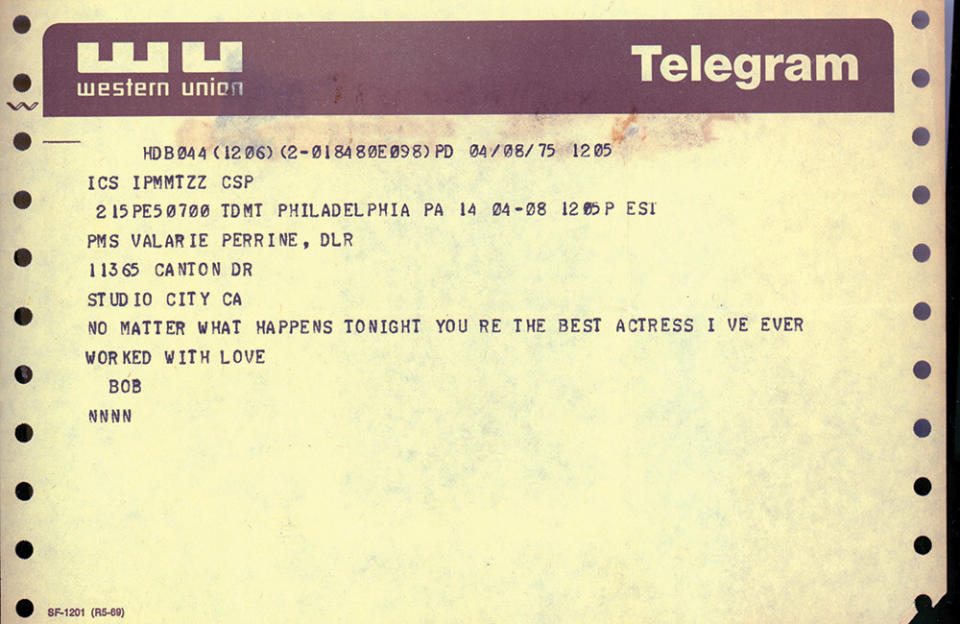

“I’m from a place called Dalton, Georgia,” Souther says in Perrine’s living room, a burgundy salon filled with mementos (like a telegram from Fosse declaring her “the best actress I’ve ever worked with”) and her movie posters (Superman and Lenny, yes, but also 1976’s W.C. Fields and Me, in which she co-starred with a “son of a bitch” Rod Steiger).

Adds Souther: “My hometown is the carpet capital of the world. The Oscars red carpet is made in Dalton.”

But Souther wasn’t interested in making red carpets — he wanted to walk on them. By his 20s, as his friends married and started having kids, he says he began to feel like he “didn’t fit in.” He was inspired to move to Los Angeles after he learned how Brad Pitt got started.

“Brad Pitt literally came out here, knew nothing about acting and was driving around strippers, and this stripper advised him to take a class with Roy London, this famous acting coach,” Souther says. “So I thought, ‘Whoa — you don’t have to go to school to study acting.’ When I found out you could do it that way, I decided to move to Hollywood.”

Like Pitt, Souther took odd jobs when he first got to town. First, he was a delivery guy for Jerry’s Famous Deli. Then he got a gig picking up fashion models from LAX and driving them around in his truck for their photo shoots.

One morning, he was asked if he’d mind driving the singer Anita O’Day, then in her 80s, to a doctor’s appointment. That led to a regular gig assisting the jazz legend. “Soon, I was driving her to Palm Springs in her 1982 gold Buick to get her hair cut,” Souther recalls. “She was a trip.”

Before he knew it, Souther says, “I made a life here. L.A.’s kind of what you make it. You make a family here because most people come out here and their family is somewhere else. Hopefully you surround yourself with good people, which I feel like I’ve been lucky to have.”

He met Perrine in the spring of 2006. She was hard not to notice: She drove a bright orange 1973 Chevrolet Suburban around their Beverly Hills neighborhood. The plates read “RATS 1,” which Souther found peculiar. But he had no idea who she was.

“She’d have her big floppy hat on and the big sunglasses — very Valerie-style,” he says. “I made up this whole backstory — that her husband must have passed away and she drives the truck to feel close to him. Boy, was I wrong.”

But there was some sentimentality involved. The truck — which still sits in her building’s garage — was a splurge after landing her first film role, playing the porn star Montana Wildhack in 1972’s Slaughterhouse-Five. It was the only car big enough to handle her dogs. As for the license plate, that was a little inside joke with herself: It was “STAR” spelled backwards.

They eventually crossed paths walking their dogs and struck up a conversation.

“She’s like, ‘What do you do?’ ” Souther recalls. “And I’m like, ‘I’m an actor. What do you do?’ She’s like, ‘I’m an actor.’ So we talked a little bit longer. And I said, ‘I’m sorry, I’m really bad with names.…’ And she rolls her eyes and says, ‘Have you ever seen Superman?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, of course.’ ‘I was Miss Teschmacher.'”

“She had that truck forever,” says Nels Van Patten (son of Dick Van Patten), who was once Perrine’s boyfriend and remains a close friend: “Even through her glamorous days, she’s never wanted to get a bigger, fancy car. Because she’s really like a cowgirl — just a girl from Arizona that became a movie star. She’s always going to keep her simple values. And I think that’s why Stacey and Valerie have hit it off — because of their simple values.”

***

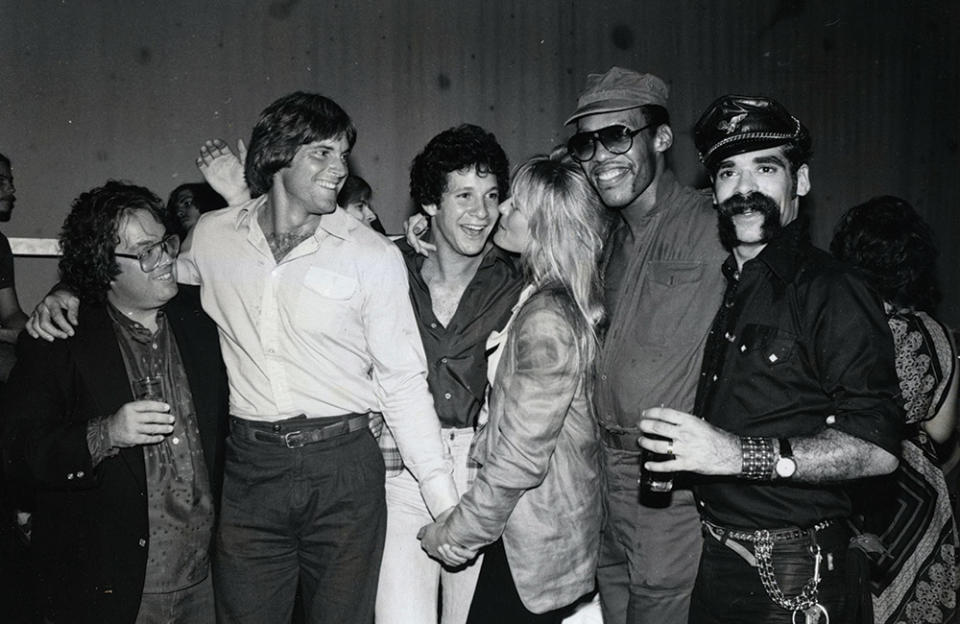

“Valerie was a lot of fun to work with,” recalls Caitlyn Jenner, 73, a newcomer to acting when cast as Perrine’s love interest, an uptight lawyer named Ron White, in 1980’s Can’t Stop the Music. “She would host glamorous parties for all of us, and she always had an army of beautiful women with her at these pool parties and lunches at her house. She was truly the hostess with the mostest and knew how to have a great time for us all.”

Perrine held those parties at her former house on Longridge Avenue in Sherman Oaks. “The minute I opened the door, I knew I had to have it,” she wrote. “Talk about flow: 6,000 square feet, with three-and-a-half acres of land, on top of a hill with a view as far as the smog would take you, at the dead end of a private road.”

Recalls Van Patten: “Rod Stewart was there, Mick Jagger. Jacqueline Bisset. You name it — anybody who was anybody in Hollywood would be at Valerie’s parties.”

“What made your parties so special?” I ask Perrine.

“Cocaine,” she replies.

The property was cared for by her majordomo, Vic, a gay Englishman who’d previously run a household for Bette Davis and who was tasked with everything from cleaning up after her dogs to laying out dress options for various social engagements.

Felipe Rose — the Village People member who dresses in Native American garb — fondly recalls spending long lunches by Perrine’s pool during the making of Can’t Stop the Music.

“One time, her mastiff was chasing Glenn [Hughes], the biker [in the band],” says Rose, now 68. “Glenn dove in the pool, and the dog dove in too. This dog was massive and he really couldn’t stay up. Glenn is yelling at us, ‘Help me! He’s drowning!’ And out of nowhere Valerie ran in and did the perfect dive right into the pool and swam him to safety. It was Amazonian.”

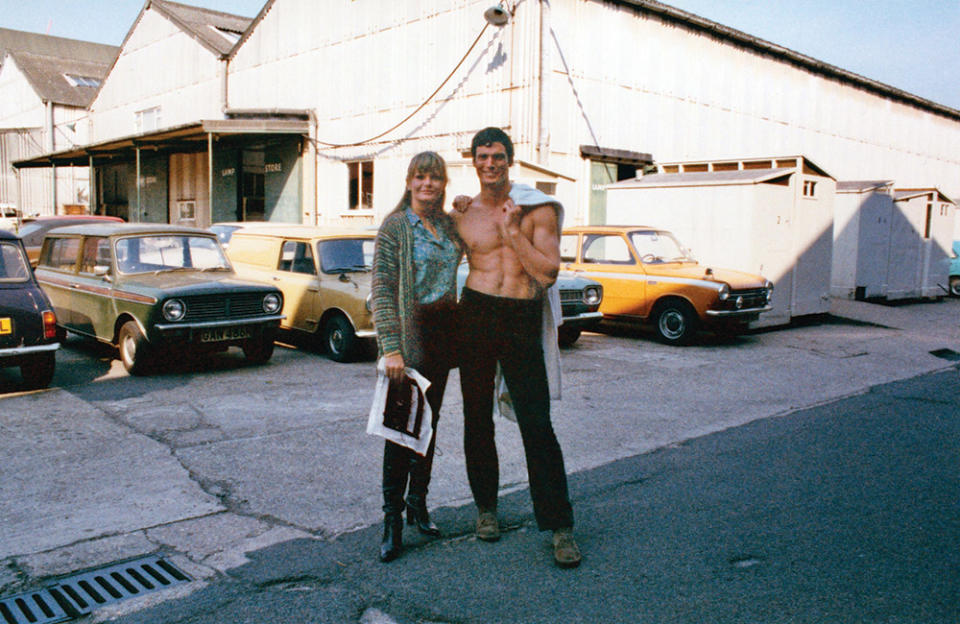

Sarah Douglas, who played the villainess Ursa in Superman and 1980’s Superman II, was a 27-year-old upstart when she shot those films back-to-back at England’s Pinewood Studios.

“Valerie was always surrounded by a flurry of wonderful activity,” Douglas recalls. “Here I was, in awe of the fact that I was working with Marlon Brando and Gene Hackman, and then in the midst of this came what I considered this enormous, glamorous Hollywood star.”

They didn’t grow close until years later, however, bonding at Superman fan appearances and the convention circuit. She stopped by to visit Perrine only weeks ago.

“She loves it,” says Douglas, 70. “She loves to see people. It’s wonderful spending time with her. She’s just got that smile and that twinkle. It’s still there.”

***

Within weeks of meeting Souther, Perrine underwent a spinal-fusion back surgery.

“I remember the doctor saying her body had the wear and tear of an NFL player,” Souther says. “She danced 12 shows a week in Vegas, in that heavy costume, up and down the stairs. She did it for nine years. It caught up with her.”

It took many months, but Perrine recovered from the surgery. Then, around 2011, the essential tremors started, first coming to her attention on a film set, when a sound engineer complained that she was trembling a coffee cup on a saucer.

“Essential tremors only come out when you’re using your arms or legs, but mainly arms,” explains her brother, who specializes in diagnosing neurological disorders. “But then she was visiting here for Christmas one year, and I looked over and with horror saw a resting tremor with her hand in her lap. That’s a Parkinsonian tremor. That was the beginning of the whole downward spiral.”

In 2014, Perrine underwent deep brain stimulation surgery, in which electrodes were placed in her brain and connected to a stimulator implanted in her chest. Souther decided to pick up a camera and document the procedure. The footage eventually made its way into a documentary short, 2019’s Valerie, which served as Souther’s filmmaking debut.

The surgery offered some relief from the tremors, but the deterioration continued. “She went from using a cane to using a walker to using a wheelchair. This was over the course of probably 2015 through 2017,” says her brother.

She now requires a hydraulic lift to get in and out of bed. About a year ago, she developed aphasia — the same condition that afflicts Bruce Willis — which affected her comprehension and speech.

But, to everyone’s surprise, it reversed, and several months ago Perrine started carrying on conversations again.

“It beats the hell out of me and it beats the hell out of her neurologist why that happened,” says her brother, who also was recently diagnosed with Parkinson’s.

“I’m sitting here with a resting tremor in the phone that I’m holding up to my ear,” he adds.

***

“Valerie had a lot of friends in Hollywood,” says Van Patten. “And then a lot of those friends, once she got sick, they didn’t come around as frequently. Stacey remained there where everybody else kind of jumped ship.”

Souther’s own parents have both died — his father in 2008, his mother in 2017. He says his devotion to Perrine hasn’t impinged on his personal life. But except for some casual dating here and there, Souther, who is straight, remains single.

“Certain girls will be like, ‘You do so much for Valerie. Like, what about you?’ And I’m like, ‘Well, she’s part of my life.’ Any girls that have stuck around long enough understand our relationship.”

“And what is that relationship?” I ask him.

“There’s no financial incentive,” he says. “She doesn’t have any money.”

That, sadly, is the case. Perrine had to sell the Sherman Oaks house after a series of bad business decisions led her to lose millions. She was overly generous to a series of younger boyfriends throughout the 1980s. She eventually moved to Europe and lived a freewheeling, free-spending lifestyle. When she finally returned to Hollywood, a new crop of ingenues had moved in — and the town had moved on.

Souther still takes random gigs from celebrities — he once drove a heart-shaped disco ball to Las Vegas in the middle of the night for David Arquette — to cover rent and has launched a GoFundMe to raise money for Perrine’s medical care.

“I mean, I don’t know how to put it,” he says. “There’s no motive for me to get anything. I just do it because I care about her and I love her. That’s the only way I know how to put it. You know?”

“Have you thought about what life would be like after she passes away?” I ask.

He pauses to consider it. His eyes well up.

“It’s going to really be painful,” he says. “But I know on the other side of that, she’s not going to be sick. Valerie is not a complainer. But she’s been going through something for over 10 years. She’s bedridden and all that. So I think of the flip side of that, and like, what I’m saying is that she’ll finally be free.”

This story first appeared in the April 26 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Eight Actors Who Have Played Willy Wonka in Films and on Broadway

Martin Scorsese’s 10 Best Movies Ranked, Including 'Killers of the Flower Moon'