AI Music Isn’t New – Raymond Scott Invented It 60 Years Ago | PRO Insight

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Raymond Scott is a name you likely don’t know. I didn’t until recently. Yet, he’s one of the most important composers of the 20th century.

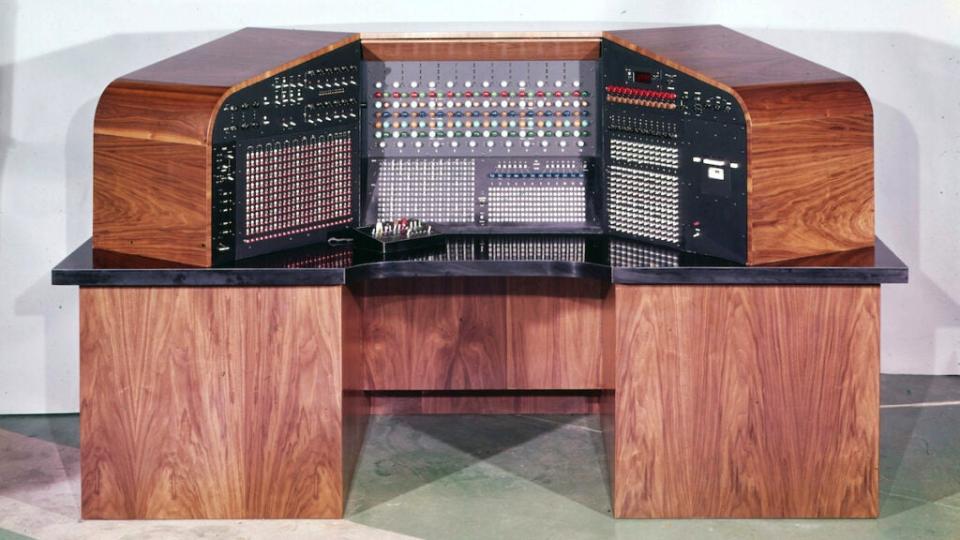

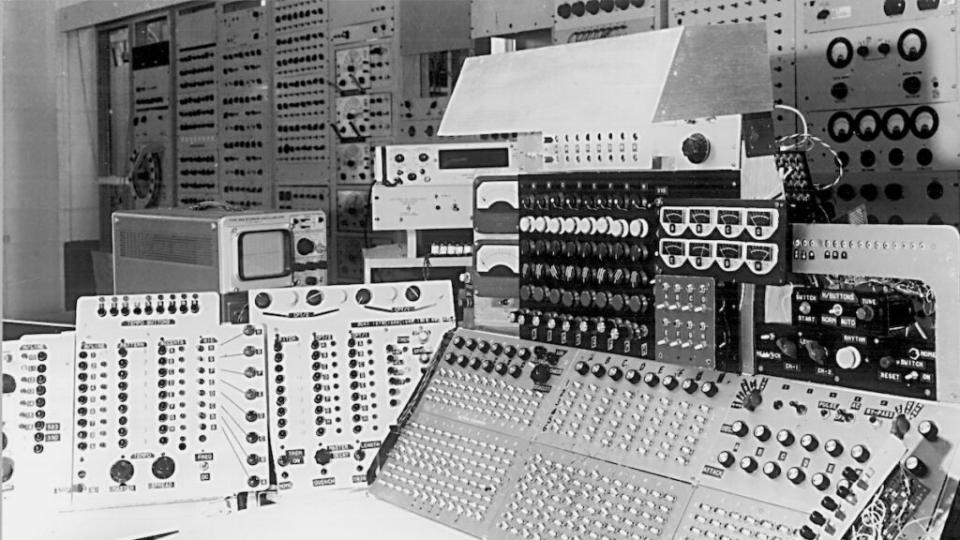

He was also a deeply entrepreneurial inventor who built elaborate machines that created some of the first electronic sounds and music. One of Scott’s machines, the Electronium, created music on its own via prompts. Sound familiar? It’s eerily similar to the generative AI technology that’s causing fervent debate today.

But Scott did this well over 60 years ago, and music legends like Motown founder Berry Gordy — a “formula man” (according to Motown’s head of operations, Guy Costa) who tried to systematize the art and business of music — courted Scott and his Electronium in the hopes of more predictably creating new hit songs.

Scott, from his youngest days and as he wrote in his Electronium patent application, was obsessed with the “artistic collaboration between man and machine.” He worked with top singers and musicians of the day and hosted his own major shows on radio and television. But his real love was electronics and the precision and exactitude they could bring to music. Whereas jazz celebrates improvisation that makes each experience utterly bespoke, Scott celebrated absolute perfection in what he called “descriptive jazz” — the goal of replicating musical performances completely without error. He built his Electronium with that perfection in mind — the lofty goal of taking human work out of the hit-making process.

Scott didn’t seek to eliminate the human element entirely. But he certainly sought to bring certainty to songwriting, which is otherwise a hit-or-miss human craft of inspiration.

And here’s the thing: His Electronium worked! Gordy was so enamored with it that he bought the machine from Scott to raise the hit rate of his hit-making factory. He named Scott director of Motown’s electronic music research and development department in the process.

Also Read:

Faced With the AI Revolution, the Entertainment Industry Can’t Pull a Napster | PRO Insight

Yet despite making a fortune over the course of his life, and being the toast of the entertainment town throughout much of it, Scott died in relative squalor and obscurity, his Electronium destined for a literal trash heap. Songs were made, although there’s no firm evidence that Motown used any of them. Something was missing — just as it was in Scott’s own life, as told in the fascinating “The Last Archive” podcast that introduced me to Scott. That something seemed to be the ingredient of humanity — the “messiness” of human creativity.

A lesson from Scott’s experiment that has keen relevance today is that there simply is something in human artistry, no matter how imperfect, that takes a creative work over the line into transcendence. In fact, it may be those very imperfect elements that ultimately connect to us all who are flawed and fallible.

AI’s precision, then — that element Gordy and Scott were chasing — may be its downfall. Master music producer and legend Rick Rubin agrees. His recently published book, “The Creative Act: A Way of Being,” tells that same story. AI can replicate. But can AI truly originate? Without knocking the potential usefulness of AI as a tool for the arts, I certainly don’t think it can, and that may be the fundamental reason why Scott’s quest foundered.

Also Read:

My Son Is Going to Film School – What’s the Point in an AI World? | PRO Insight

Scott remains a beloved figure in the music world. Tech-forward superstar group Gorillaz based its song “Man Research (Clapper)” on an Electronium-created hook, and electronic pioneers like Mark Mothersbaugh of Devo count themselves as Scott devotees.

That pull is so strong, in fact, that Mothersbaugh owns Scott’s Electronium. He purchased it from Scott’s wife shortly after the musician’s death in 1994. I asked Mothersbaugh what motivated him to buy it, and he told me that he felt an almost existential need to save it from otherwise “going into the dump.” He couldn’t let that happen to something that represented so much to him in terms of what he holds dear as “a conceptualist,” inventor and pioneer in music experimentation.

“That’s why I identify with him,” Mothersbaugh told me. “I could see the same thing happening to my archives.”

Mothersbaugh has yet to find a way to make the Electronium function again. Until then, we may never know the music-writing machine’s ultimate potential. But Mothersbaugh definitely sees parallels between Scott’s quest and the AI music debate today.

I asked Mothersbaugh whether he believes AI-generated music threatens the human act of creativity.

“I think AI will match or surpass humans eventually,” he said. “It’s not even interesting to guess. But it will be fun to see what happens. I’m not afraid of it.”

For me, I’m not so sure. I don’t fear AI. But I choose to believe that only we fallible beings carry that special ingredient of humanity necessary to make music and art truly original and transcendent. I take solace from the story of Raymond Scott and his Electronium. It may have been a flawed attempt at pushing art forward with technology. It’s also a very human one that ultimately underscores the undefinable, unprogrammable elixir that fuels true artistry and creativity.

For those of you interested in learning more, visit Peter’s firm Creative Media at creativemedia.biz and follow him on Twitter @pcsathy.

Also Read:

From Fake Drake to a Fan Frenzy: AI Can Help – Not Just Hurt – the Music Business | PRO Insight