AI and the Law: It’s the ‘Wild, Wild West’ Out There

This is Part Six of a series about AI and its impact on Hollywood. Keep reading WrapPRO for upcoming stories on AI and its effects on animation and production. Level up your entertainment career and subscribe!

Did you happen to catch “Heart on My Sleeve” when it went viral in April? It was a catchy little duet, only about two minutes long, between two pop superstars, Drake and the Weeknd, and it quickly racked up 15 million streams on TikTok and another 600,000 on Spotify.

Only problem was, Drake was fake, and so was the Weeknd.

The song, which sounded real enough to fool millions of listeners, was an artificial tune created with AI by an anonymous poster calling him- or herself Ghostwriter977. And while the ditty was removed from social media before it could land on Billboard’s charts — after copyright infringement complaints by Universal Music Group, home to both Drake and the Weekend — its fleeting appearance on the internet was yet another giant red flag for the entertainment industry on how artificial intelligence could end up upending everything.

Also Read:

From Fake Drake to a Fan Frenzy: AI Can Help – Not Just Hurt – the Music Business | PRO Insight

Of course, music copyrights have always been a messy space. Did Led Zeppelin steal from Spirit? (No, according to a U.S. appeals court ruling in 2020.) Did Ed Sheeran steal from Marvin Gaye? (No, a jury ruled in Sheeran’s favor last week.) Robin Thicke, the Rolling Stones, Katy Perry, Taylor Swift, Vanilla Ice — they’ve all been embroiled in various and sundry infringement suits. In this day and age, with artists sampling each other’s work as an accepted part of the creative process, the lines between fair use — or even just inspiration — and outright theft are often blurry at best.

But AI is an altogether different beast. It’s one thing for a human musician to sample another artist’s vocal riff in order create a wholly new and transformative sound; it’s quite another for a computer to “scrape” the internet — trawling through millions of pieces of data on the web — to concoct a new song by a singer who in fact had nothing to do with its creation. Can that be called fair use? Or is total rip-off a more apt description?

And it’s not just the music world that’s wrestling with these 21st-century problems. Pretty much anything that can be copyrighted — words, photographs, paintings — is now being generated by AI. Art created by artificial intelligence is by its very nature an amalgam of bits and pieces of preexisting content — that’s how AI operates, by sucking up data from the internet, analyzing it and then reconfiguring it into so-called original works. Do the human creators of those bits and pieces retain the copyright over their contributions? Who owns a work of art if it’s wholly or even partially generated by AI? Can a computer even possess a copyright over its creations? Or are only carbon-based lifeforms afforded rights?

As of now, the answer to those questions is… nobody has a clue. Currently, Hollywood is flying blind when it comes to figuring this all out. All the industry can do at this point is watch and learn as various AI copyright cases make their way through the courts. Below, a sampling of some of those suits and what hints — if any — they offer for the future of show business.

Also Read:

ChatGPT Is Copying Human Creativity on a Huge Scale – But How Do Artists Get Paid? | PRO Insight

Thaler v. U.S. Copyright Office

In 2012, long before AI was part of our day-to-day lexicon, a computer scientist by the name of Stephen Thaler created an artwork titled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise,” generated solely by an AI software program he created called DABUS. It would have been nothing more than a pretty floral scene, perhaps shown only to Thaler’s friends and family. However, in November 2018, Thaler decided to file for copyright protection of the work with the U.S. Copyright Office. The office refused the request, stating that the work lacked “the human authorship necessary to file a copyright claim.”

That could have been the end of it, but Thaler has spent the last several years fighting the decision, arguing that the Copyright Act isn’t solely relegated to the purview of human creations. In June 2022, he filed a lawsuit against the office with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, asking that the decision be overturned. In August, the court upheld the Copyright Office’s decision. Thaler then filed a petition for review with the Supreme Court. On April 24, the court declined to hear the case.

For now, at least, that seems to settle the matter: Artwork created by AI is not copyrightable. The repercussions of that decision could turn out to be enormous. If a screenwriter uses AI to write a script, for instance, and somebody steals part or all of that script, that screenwriter may not have much recourse in court, since he or she won’t be able to copyright that work.

“You cannot sue for infringement until your work has first been registered with the Copyright Office for copyright protection,” explained intellectual property attorney Erica Van Loon at Nixon Peabody. “So the rules regarding what constitute human authorship are going to need to be looked at closely.”

Getty Images v. Stability AI

Stock image company Getty Images is currently suing Stability AI, maker of AI art-generation software, which created a tool called Stable Diffusion. Getty claims the company copied more than 12 million of its images to train Stable Diffusion to generate its own images. In its Feb. 3 lawsuit filed in Delaware, Getty Images claims the move was “a brazen infringement of Getty Images’ intellectual property on a staggering scale.”

“What they’re saying is that the algorithm the AI software is using is scraping copyrighted content, and that’s unlawful,” said Van Loon. “That’s why lawsuits are being brought against the actual software makers.”

Also Read:

Chatbots Flip the Script: For Screenwriters, AI’s Evolution Brings New Tools and New Fears

According to court documents, Getty argues, “Often, the output generated by Stable Diffusion contains a modified version of a Getty Images watermark, creating confusion as to the source of the images and falsely implying an association with Getty Images. While some of the output generated through the use of Stable Diffusion is aesthetically pleasing, other output is of much lower quality and at times ranges from the bizarre to the grotesque. Stability AI’s incorporation of Getty Images’ marks into low quality, unappealing, or offensive images dilutes those marks in further violation of federal and state trademark laws.”

Van Loon noted that Stability AI and other generative AI companies currently being sued (see below) are using the defense their work constitutes “fair use.”

“They argue that the algorithm takes a prompt from somebody and spits it out, but it’s just a fragment of all the information out there,” she said. “And they argue that doesn’t infringe on anyone’s copyrighted work.”

Should Getty win its case, then there’s a possibility that going forward generative AI companies will either have to license the content they wish to use or find themselves guilty of copyright infringement.

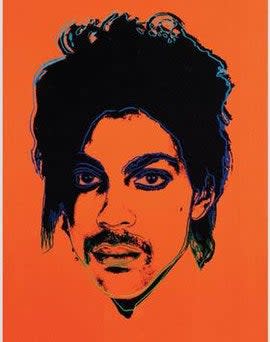

Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Lynn Goldsmith

Although not an AI case, this one, currently before the Supreme Court, dovetails neatly with the Getty Images suit, since it involves fair use and could have a major impact on AI case law.

Warhol created a series of images based on a photograph taken by Lynn Goldsmith in 1981 of the late artist Prince and copyrighted the work. The court will decide whether Warhol’s work transformed the original image enough to qualify the work as a “fair use” of the photo, thereby allowing Warhol’s successors to continue to license his work for commercial use without Goldsmith’s permission, and also deny Goldsmith any financial compensation.

As with the Getty case, Van Loon said she believes the decision will factor heavily in how generative AI is dealt with in copyright cases going forward.

Sarah Andersen, Kelly McKernan and Karla Ortiz v. Stability AI, Midjourney and DeviantArt

Cartoonist and illustrator Sarah Andersen, illustrator Kelly McKernan and visual artist Karla Ortiz filed their suit in January in San Francisco Federal Court against all three companies for arguing the generative AI tools are “21st-century collage tool[s] that remix the copyrighted works of millions of artists whose work was used as training data.”

As with the Getty case, the plaintiffs are also arguing their work has been licensed without their permission or compensation. According to court documents, the images each artist is suing over are “derived images compet[ing] in the marketplace with the original images. Until now, when a purchaser seeks a new image ‘in the style’ of a given artist, they must pay to commission or license an original image from that artist. Now, those purchasers can use the artist’s works… along with the artist’s name to generate new works in the artist’s style without compensating the artist at all.”

On April 19, the attorney representing the defendants asked that the suit be dismissed on the grounds that the plaintiffs cited no specific works of art that were used and that there is no similarity between the artists’ work and the images generated by each of the three AI companies.

The real question that the court needs to look at is whether these generative AI companies are little more than a “collage” tool. It’s an argument that may not stand up in court. Would the court rule that all three companies have abused copyright on such a massive scale? And if so, what would such a ruling do to these nascent companies? Would they be forced to go back to the drawing board and recalibrate how they operate? These are questions that can only be answered once a decision is handed down.

Kris Kashtanova v. U.S. Copyright Office

While this issue never went to court, it was an important case in terms of how the Copyright Office dealt with and is continuing to grapple with the use of generative AI.

Kris Kashtanova obtained copyright protection for their 18-page graphic novel “Zarya of the Dawn,” in September 2022. However, once Kashtanova posted on their social media that they had used a generative AI program called Midjourney for the images in their novel, the Copyright Office reviewed the case and granted only partial copyright to Kashtanova, stating Kashtanova “is the author of the Work’s text as well as the selection, coordination and arrangement of the Work’s written and visual elements,” not the images themselves.

While Kashtanova didn’t file a suit against the Copyright Office’s decision, their attorney did send a letter to the office in November 2022, arguing that full copyright should not be revoked because they “authored every aspect of the work with Midjourney serving merely as an assistive tool” and because the text and images together were Kashtanova‘s “creative selection, coordination and arrangement.”

Kashtanova hasn’t sought redress at this time. However, perhaps because of the publicity the case generated, the Copyright Office felt compelled to issue a clarifying order in March in an effort to address these rising issues. The order states that applicants who use AI in their work now have to disclose that in their copyright application.

New issues emerging

It appears that for now, the issue of copyright and AI will continue to be a game of Whac-A-Mole as new potential cases emerge. Intellectual property attorney Marc Misthal of Gottlieb, Rackman & Reisman in New York raised the potential issue of generative AI being asked to write a sequel to a particular work.

“Often a sequel will be considered a derivative of the original,” he said, “but if the AI is not working at the behest of the owner of the original work, the derivative it creates could be an infringement. In that case, if there is infringement, who is liable? The party that asked the AI to create the derivative work? The company that operates the AI? Both?”

Van Loon believes no matter what happens going forward, there cannot and will not ever be a one-size-fits-all solution for these types of cases.

“It always has to go back to a case-by-case analysis,” she said, adding that’s why it’s currently the “Wild, Wild West,” when it comes to figuring out what works are protected and what the alleged infringements may be.

This is Part Six of a series about AI and its impact on Hollywood. Keep reading WrapPRO for upcoming stories on AI and animation and production.

Read Part One: AI and the Rise of the Machines: Is Hollywood About to Be Overrun by Robots?

Read Part Two: How Hollywood’s Guilds Are Preparing for the Dangers – and Benefits – of AI

Read Part Three: This Story Was Not Written by a Robot: AI and the Future of News Media

Read Part Four: The Chatbot Stays in the Picture: How AI Could Transform Acting

Read Part Five: Chatbots Flip the Script: For Screenwriters, AI’s Evolution Brings New Tools and New Fears

Also Read:

AI and the Rise of the Machines: Is Hollywood About to Be Overrun by Robots?