How will AI affect the books we read? Columbia authors face fears, opportunities

Housed within a poem about death, Charles Bukowski penned a poignant description of the writing process itself:

"And remember this: the page you are looking at now, I once typed the words with care with you in mind under a yellow light with the radio on."

The details might vary, but many writers would see themselves in the spirit upholding Bukowski's words: the pouring out of their souls, their dance with readers beginning long before a final draft emerges.

As the publishing world fears, flirts with and — in a few cases — embraces the integration of artificial intelligence, or AI, questions rise up, surrounding the sort of moment Bukowski described. How does our relationship to the written word change if there is no yellow light, no radio on, no you in mind — or, at least, less of these things?

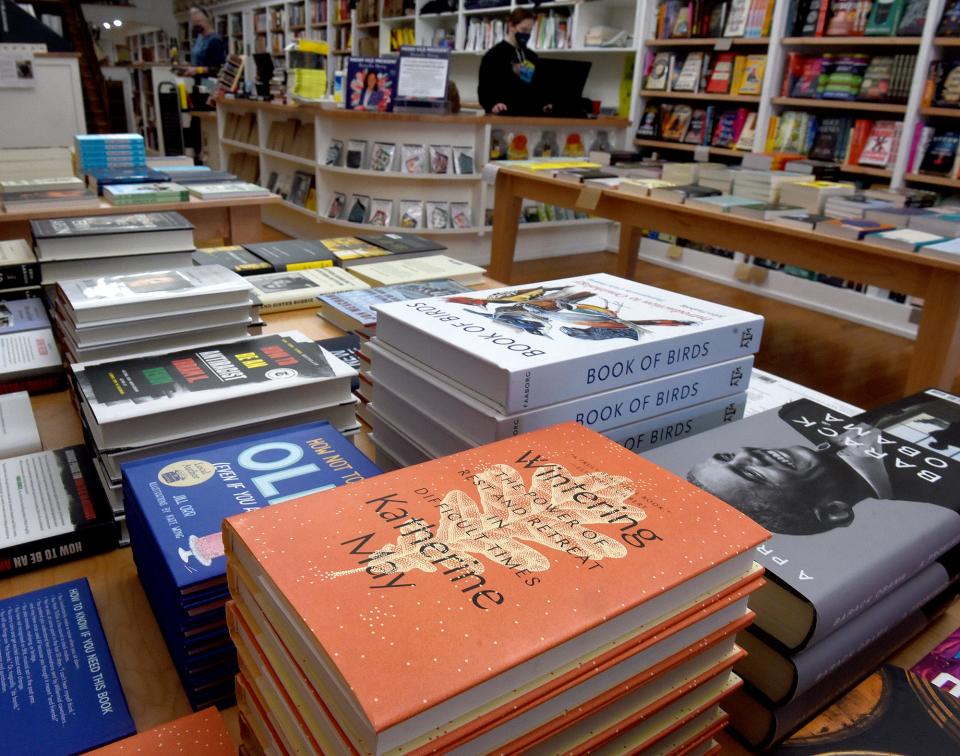

With nurturing colleges and universities, the nationally-recognized Unbound Book Festival and strong independent bookstores, Columbia is a vibrant literary community. Several authors who possess a local zip code — or once did — spoke with the Tribune about their thoughts on AI, examining the present and peering over fences at the future.

Their feelings were understandably mixed, and their sentiments aware of how literary and technological landscapes are changing, even daily.

Telling the difference between AI and manmade literature

Discourse around AI and publishing tends, for now, to divide into two loose categories or sets of questions.

First, will the use of AI open the floodgates for cheap, even counterfeit, content? And can authors use AI tools to make their process more productive, maybe even more provocative?

For the moment, Alex George remains relatively unbothered by what he knows about AI and literature. George sees the publishing process from nearly every angle as an accomplished novelist, the founder of Unbound and owner of Skylark Bookshop on Ninth Street.

George's posture relies on two notions: technology isn't yet strong enough to mislead — or lure — readers, and those readers are sharp enough to sniff out the "human spirit," or lack thereof, in a book.

AI-generated stories might be novel or even entertaining to some, George said, but some of those same readers will grow bored with AI.

More: Columbia's Skylark Bookshop named one of '150 Bookstores You Need to Visit Before You Die'

George laid out a hypothetical scenario in which a reader asks an AI tool to generate a story in the style of Stephen King featuring specific, self-selected details. Something will always feel slightly off about the results, he said.

"The reader knows it’s not Stephen King — it’s Stephen King-adjacent. No matter how good it is, you know it’s not the real thing," George said.

A day may come, George said, when AI-produced work more closely resembles words penned with human elements such as blood, sweat and tears. But he holds a conviction that readers will always sense some difference.

"No matter how good the technology gets, there’s a kind of internal bullshit detector. I’ve just gotta believe that," he said.

Fiction readers compose "a sophisticated market," Jess Bowers said in an email. The University of Missouri alum now lives in St. Louis and teaches at Maryville University. Her debut story collection, "Horse Show," hits the atmosphere April 9.

"Most of us assume that a key part of what people are looking for when they read fiction is human experience, human connection — something ineffable that AI cannot replicate," she said. "... Most readers don't want to waste their time and money on 'content' no human cared enough to spend time writing."

There have always been readers who invest literature with "mortal stakes," to use a Robert Frost phrase, and those who come to books for catharsis or emotional release, said Phong Nguyen, an MU professor and the author of novels such as "Bronze Drum."

Readers seeking the latter qualities may be able to find those in AI-produced work in the "near future," Nguyen said, which he doesn't see as an "essential problem." Readers who hold literature as a "reason to live" will face a more "interesting, dynamic experience," he said, as they consider an author's vision, the sorts of thoughts the work provokes and other compelling factors.

More: How Columbia author Phong Nguyen brings an ancient Vietnamese epic to life

Why some authors fear losing control over their work

Perhaps the greatest outrage so far among authors relates to scraping, a process in which AI models train themselves by reviewing a vast quantity of published works. Last year, writers pressured Benji Smith into shuttering his Prosecraft website, which had scraped more than 25,000 titles by more than a thousand authors, according to the Sydney Morning Herald.

Smith designed his site "to help aspiring writers improve their work by comparing aspects of their prose to the work of authors they admire," the article notes.

But authors recoiled over the lack of permission, compensation and the fear "their prose could be used to create new material that is sold for profit without their involvement or approval," journalist Nell Geraets wrote.

Several of George's novels have been scraped. The prospect doesn't thrill him, but he knows every author loses degrees of control over their work once it's in the world, he said.

This lack of control introduces worries for Sean Frazier, the Columbia-based author of such novels as "Mage Breaker" and the forthcoming "The Last Available."

"Artists have very few rights and we often have to compromise in order to get our stuff out there," Frazier said in an email. "We're merely compromising a lot more, now, and without our knowledge in many cases."

Frazier fears the proverbial slope growing muddier, more slippery beneath authors' feet. He pointed to news outlets laying off writers or outsourcing some of their work to AI for the sake of saving a few bucks.

Already, multiple parties within publishing are reacting to the specter of more AI-produced titles. Last year, retail giant Amazon adjusted its rules, limiting self-published authors to releasing — a still-surprising — three titles per day on its site.

The change came, as Frazier noted, after author Jane Friedman found AI-generated titles released dishonestly under her name.

The ability to use AI for gain with "absolutely zero effort or skill" represents "everything that's wrong with capitalism," Frazier said.

Ways authors might use — and respond — to AI

While some authors express a hesitant wait-and-see attitude toward the use of AI tools to organize or ease the creative process, others have already claimed them as a positive.

Early this year, prize-winning Japanese author Rie Kudan estimated using AI to compose around 5% of her book "The Tokyo Tower of Sympathy." AI tools allowed Kudan to express herself in ways that initially felt too private and to unlock certain elements of her creativity, she said in reports.

And a subset of the writing community expressed concern on social media last year when poet Lillian-Yvonne Bertram won a chapbook contest, in part using computer programs to generate language. Upon a closer, clearer look at Bertram's aims, the poet used these tools very deliberately, critiquing prejudices programmed into the tools themselves.

Describing her work, a Northeastern University dispatch said Bertram "examines how ubiquitous and purportedly neutral computer code helps scaffold racial bias to the systems that sustain it."

George shows no interest in using AI tools.

"I don’t want anything to get in between me and the act of creation," he said. "... When it’s hard and I work it out, that’s where the joy comes from. Why would you do anything that’s going to dilute (that)?"

Frazier agrees, despite seeing "fascinating and helpful applications" in more data-driven pursuits.

"I'm staunchly against AI being involved in any creative process if it's a job a human can accomplish," he said.

Whatever the era of AI looks like, Nguyen sees opportunities laid before writers — not to write with these technologies, but to write around them.

"I’m more interested in the writer’s response to AI than to AI itself," he said.

Every new creative tool spurs reactions, recalibrations, Nguyen said. The camera's popularity nudged artists toward more abstract imagery; motion pictures ushered fiction writers away from detailed description, toward "narrative propulsion and forward momentum," he said.

He believes AI will cause writers to discover fresh ways to set themselves apart, to demonstrate "proof of life."

"It becomes no longer about simply producing an effect," Nguyen said. "... If AI turns out to be able to write a story that can make you laugh or make you cry, it becomes beholden to the artist to go beyond those effects and try to produce something more complex, something maybe unprecedented. I can’t even anticipate what the next development in writing is going to be, because it will be a reaction to technologies that have yet to develop into their completed form."

This moment, and those to follow, will make it incumbent on writers to invent untold ways to touch what is "essentially human," provoke even more complex thoughts and feelings, and explore the previously unexplored, he added.

With AI and publishing, is the future happening now?

Frazier's most recent novel, "Mage Breaker," imagines a world in which people rely on magic to accomplish everything.

"In doing so, they've inadvertently given up a decent amount of their autonomy without realizing it," he said.

More: How Columbia's Sean Frazier handles magic's blessing, curse in new fantasy novel

Possible parallels aren't lost on him, as creators find it "increasingly difficult to remain separated from AI in a business model that pushes companies toward using it in every way they can," he said.

His concern "grows daily," he said, and leaves him with more questions than answers.

"Will there be a market for my books anymore? Will publishers want to pay me when they can enlist AI to do the same thing faster and for free? Will we all become so reliant on AI that we'll forget what actual human creativity can do?" he said.

Authors identified a few guardrails moving forward.

"It's been heartening to see the literary community band together, similar to what we saw with the Hollywood writers' strike," Bowers said. "People are aware that precedents need to be set. More and more journals are specifying 'No AI' in their submissions guidelines, and writers are fighting for agency over whether or not their intellectual property gets scraped."

In George's experience, publishers are using contract language to ensure authors aren't handing in AI-generated work. And bookstores like Skylark maintain personal relationships with presses, creating mutual investment in each other's good.

Ultimately, as technology improves, readers will face a choice. But George already sees readers making positive choices, buying from independent bookstores instead of online Goliaths for a thousand little, intangible reasons, he said.

Bookstores make it easy to make these choices, he added, by providing an experience no technology can replicate — from the smell of new books to the very human touch extended in a bookseller's recommendation.

And readers can play an active part in keeping their art human by doing something they're already good at, Bowers said — paying attention.

"Pay attention to where individual authors and publishers stand on AI usage in art and avoid those who don't echo your ethics," Bowers said. "Familiarize yourself with what AI-generated cover art looks like and call it out when you see it. Respect the immense time, focus, and craft necessary for a human being to write well. Demand human expression, not soulless AI content."

Authors and booksellers will keep trusting in, and underlining, the human element because, as Frazier said, it's what makes "art mean something."

Aarik Danielsen is the features and culture editor for the Tribune. Contact him at adanielsen@columbiatribune.com or by calling 573-815-1731. He's on Twitter/X @aarikdanielsen.

This article originally appeared on Columbia Daily Tribune: Columbia authors face fears, opportunities as AI enters the book world