Go Ahead, Call Joyce Chopra a ‘Lady Director’ One More Time

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When filmmaker Joyce Chopra was coming of age in post-World War II New York, she ran into a serious problem: She’d never seen a film directed by a woman. Even the film history books she read didn’t make mention of what Chopra herself would eventually become: a “lady director.”

After more than 50 years in the business, Chopra is reclaiming that eye-rolling moniker for her first memoir, “Lady Director, Adventures in Hollywood, Television and Beyond,” an insightful, emotional, and often quite dishy rollercoaster ride through her life and career. At 86, Chopra is as curious, clever, and damn fun to talk to as ever, all of which is reflected in her eye-opening memoir.

More from IndieWire

'Smile' Director Parker Finn Still Loves Jump Scares -- and Doesn't Care If You Don't

Anya Taylor-Joy on the 'Smorgasbord' of Genres in Dark Comedy 'The Menu'

Out November 22 from City Lights Publishers, “Lady Director” follows Chopra through her early, revelatory documentary career, the making of her Sundance winner “Smooth Talk,” the incredible disappointments that followed (like nearly being kicked off “The Lemon Sisters,” starring Diane Keaton), and her eventual move into television, where she directed films about everything from an American Girl doll to Marilyn Monroe (long before Joyce Carol Oates’ “Blonde” was adapted at Netflix).

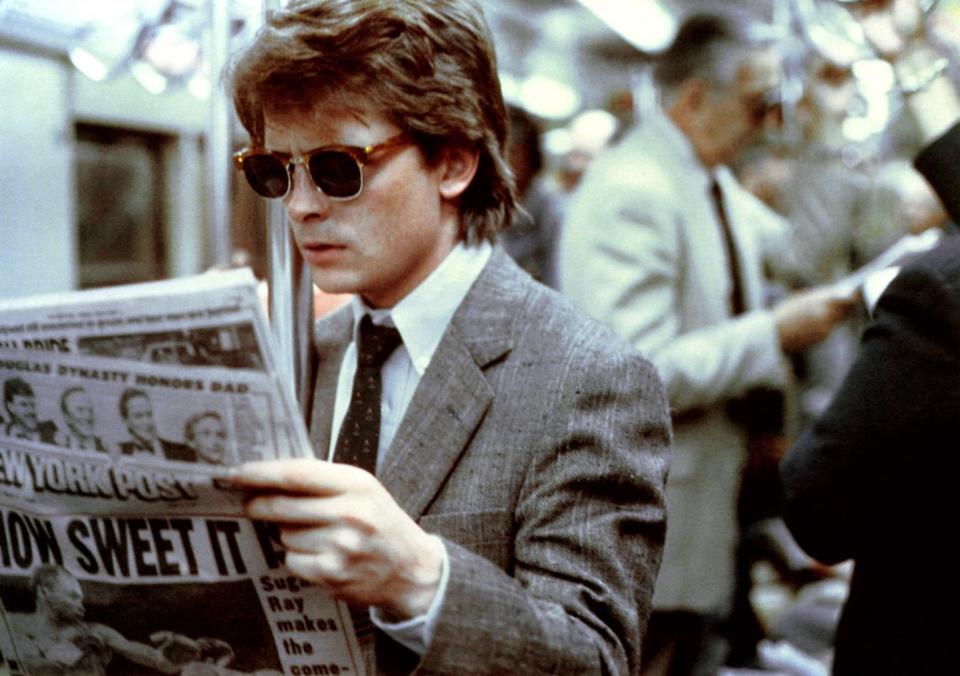

Ahead, Chopra speaks to IndieWire about the genesis of the book, how the world has changed (or maybe not) for directors who happen to be women, some of her more upsetting professional experiences, her favorite film, and what she really thinks of that new “Blonde.” Plus: an exclusive excerpt from “Lady Director” in which Chopra chronicles what happened when she was let go from directing “Bright Lights, Big City.”

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

IndieWire: When you first start writing the book, what sort of tone did you want to strike?

Joyce Chopra: I never thought about it, because I didn’t think I was writing a book. I didn’t intend to write a book, let’s put it that way. I was just going to write to keep busy during the pandemic. I wasn’t making any movies, and I just felt, “What should I do?” And my daughter said, “Well, why don’t you write a memoir?” So I was just fooling around, and I just kept adding to it.

The book had a huge amount more, and my editor took out, quite wisely, a bunch of stuff, because I could just go on. You start to talk about so-and-so, and then you tell about how they got to be where they are, and then before you know it, it’s double the length. I’m used to working on scripts and I love dialogue, so here and there I couldn’t resist saying what I remembered people saying.

The title of the memoir is obviously a little cheeky. Do people seem to get it?

I mean, so far, yes. Yes, exactly, that’s me! What would they say, a woman director? A girl director? I don’t know, but I was definitely in a category.

©International Spectrafilm/Courtesy Everett Collection

What do you think when you hear the term “female director” these days?

“Oh, God, when are you going to stop?” That’s my attitude. Yeah, just stop. Stop, enough already.

In the beginning of the book, you write about how much of your actual education and your early career aspirations were influenced by a lack of information about other female directors. Do you think that has changed in the intervening decades?

Oh, certainly it’s changed. It’s changed only in the last three or four years though, it’s as recent as that. When I was hired to direct my first episodic television in 2002, there were hardly any women directing episodic television. If you look at it in just the last few years, the percentage is something like 40 percent, it’s amazing. It’s since the #MeToo movement, definitely.

I know how things are going with features [because] I get the Directors Guild bulletins. This week, there are 13 films being screened at the Directors Guild building in New York and L.A., and of the 13, four are by women. That’s a huge improvement.

Lately, there’s been much more talk about who can or should direct a certain kind of project, like should only women be directing “women’s stories.” What do you make of that?

I don’t even know what a woman’s story is, does it mean that the woman is the lead? I would put it more that it’s a woman’s point of view, and that goes back to the heart of, how do you set up a shot? I mean, whose scene is it? Everything in “Smooth Talk” is from Connie’s [Laura Dern] point of view. There are men who are as capable of doing wonderful films about women and have made dozens of them. And I know how to film action sequences, I had to do them in a lot of those TV movies.

My husband [Tom Cole] and I wrote “Smooth Talk,” and in his obit, Laura Dern wrote something [about working with him] like, “I couldn’t believe I was sitting with this 50-year-old MIT professor explaining to me what a young teenage girl is feeling — and he was right.”

©United Artists/Courtesy Everett Collection

The chapter about your experience with “Bright Lights, Big City” was very upsetting even to read, because you’re so emotionally honest and open about how it felt for you at the time.

I’m glad if I was able to convey that. [I was] gutted, it was devastating, it was. For two years after, I couldn’t talk about it without, literally, my hands trembling. What made it worse is that my husband was also fired from the same thing, and so we were cold comfort for each other. It was awful.

How did writing that section of the book feel?

Oh, it was hard. Yeah, it was hard. Also, it was hard to convey what it was. So I stuck as much to my version of the facts, and it’s always who’s writing the history. Sydney Pollack, who fired me, is dead, but if he were alive, I would really love to know what he would say, or whether he would challenge what I wrote. Probably would.

There are other people in the book who you write about, not always in sunny terms, who are still alive. Did you speak to any of them before you decided to publish?

Diane Keaton? I haven’t, I was thinking of writing to her. I don’t know, I really don’t know. The person I really feel terrible about is Michael J. Fox. We were very friendly during [“Bright Lights, Big City”], it was not just a month of shooting, but it was prep [time too]. He’s a very dear person, and I felt so badly that I couldn’t tell him what was going on. I’m thinking of sending him the book, and then I thought, “Well, why do you want to do that? Because you want to write his view of you?” And I thought, “I should just let it alone.”

I wonder if Diane will… well, what could she say? That’s what happened [on “The Lemon Sisters”].

Can you believe that this guy [co-producer Joe Kelly] calls me into his office and says that Diane wouldn’t do it herself? We were so friendly, and then suddenly this guy says, “Diane would like you to quit,” because then they wouldn’t have to pay me. If they fired me, they would’ve owed me my whole salary. They couldn’t afford to do that.

©Miramax/Courtesy Everett Collection

But as you wrote in the book, you still had to show up to the meetings to prove you’re doing as much as you can.

I was so desperate to get my name off of that film that it overrode, to put it mildly, hesitation. And then there’s [producer] Harvey Weinstein [in the meetings] saying literally, “Go away, no one wants you here.” Who’s ever said that to you? As I write, “How did I get to this point in life that somebody would say that to me?”

After “The Lemon Sisters,” you enjoyed quite a bit of success in making TV movies. People are always debating film versus TV but do you see a divide between them anymore? Did you at the time you were making TV movies?

The TV movies that I made weren’t movie movies, as far as I was concerned. I tried as best I could, but they’re not the same. At least not for network television. I’ll tell you my favorite movie, though: “Molly: An American Girl on the Homefront.”

I had no idea what my agent was talking about [when it was offered], but they wanted a live-action version of the American Girl stories, and I loved being back with teenage girls. It was the last TV film I did, and we had enough money for me to have time to do it. Not a lot of time, but more time than the usual TV movie. But I just had such a good time doing that, I think it was because I was back in my childhood, in the ’40s.

Courtesy Everett Collection

Recently, your 2001 miniseries “Blonde” has been back in the news because of Andrew Dominik’s Netflix version, which also adapted the Joyce Carol Oates novel. How do you reflect on your version?

I was so happy with that because when it was first released, it got a few good reviews, but let’s say, in the big papers like The New York Times, they trashed it.

I have my theory about that, which I’ll pass on to you: I don’t think anybody should do any films about Marilyn Monroe, because everybody personally owns her. So no matter how good mine might have been, we still had people who said, “Oh, that’s not the real Marilyn.” But it’s not supposed to be the real Marilyn.

What did you think of Andrew Dominik’s “Blonde”?

I found it boring, because she just cries from one scene to the other, over and over again. Anyway, enough of that.

Read an exclusive excerpt from Joyce Chopra’s “Lady Director: Adventures in Hollywood, Television and Beyond” on the next page.

Best of IndieWire

New Movies: Release Calendar for November 18, Plus Where to Watch the Latest Films

51 Directors' Favorite Horror Movies: Bong Joon Ho, Quentin Tarantino, Guillermo del Toro, and More

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.