The Agony and The Ecstasy of Mr. Chow

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

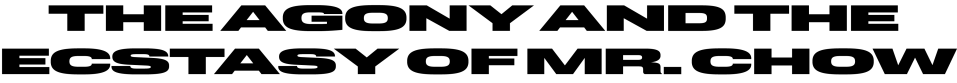

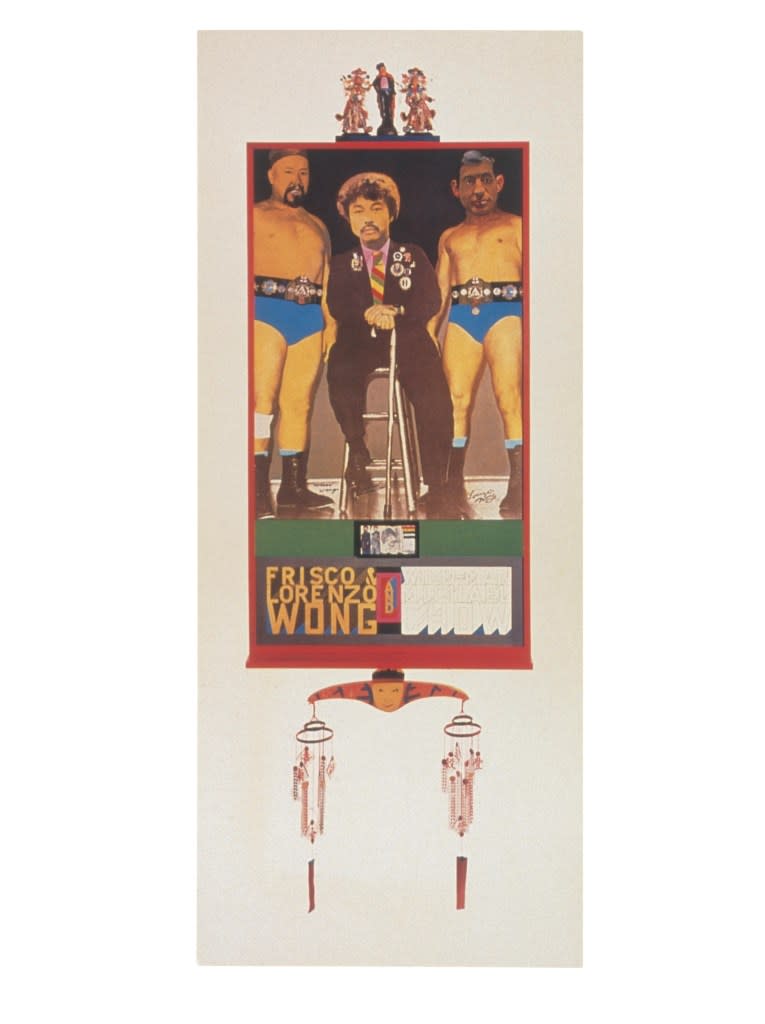

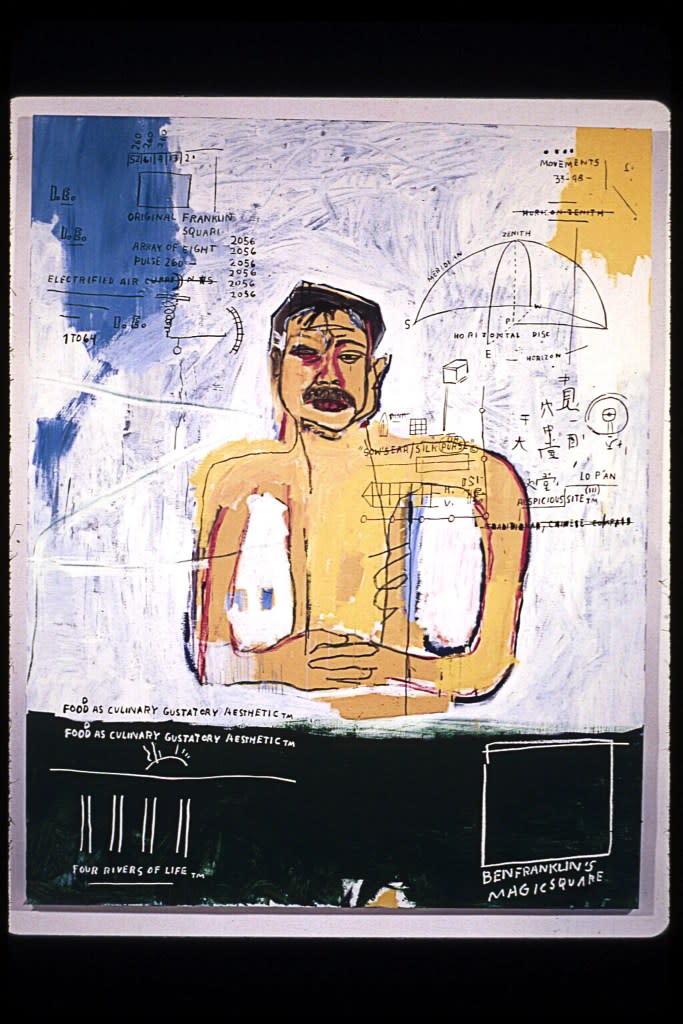

Artwork by Michael Chow

By Jeffrey Deitch

Abstract painting is like a recipe. … I’ve been dealing with recipes for 54 years, so if I can’t paint, who in the world can?”

Michael Chow

You know his name. You almost certainly know his bespectacled face. Chances are good you’ve eaten his food, maybe less so you’ve experienced his art (though he’s hellbent on changing that last part). Equal bits restaurateur, raconteur, painter and performer, Michael Chow is in some ways as famous as the rarified clientele who for decades have supped minced squab in lettuce leaves and clinked cocktails at his swinging eponymous eateries, yet in other aspects, as enigmatic as a person could be.

The recent HBO documentary aka Mr. Chow changes all that by putting the man center stage, peeling back layer after revelatory layer of his extraordinary life story, including his upbringing in pre-cultural revolutionary China, his tumultuous relocation to the West, the childhood health struggles that pre-ordained his core outlook on life, the sheer grit and moxie it took to build his dining empire and now and his dogged determination that you will, by gosh, know him as a fine artist. Here, art dealer, curator and gallerist Jeffrey Deitch sits down for a one-on-one with Michael Chow.

Jeffrey Deitch: To start, the reaction to the HBO documentary aka Mr. Chow has been so enthusiastic. I have a minor role in the film, and I’ve received dozens of calls and notes from people–artists, collectors, friends, even top people in Hollywood–saying, “This film is great.” Of course, everyone was amazed by the opening scene where you reel off the opening shots of all those great films. Sometimes when you have a movie like this, it’s all staged, but I’ve been present many times where you’ve invited people to ask you to do this and I’ve never seen you not know the answer, in precise detail.

Asthma prevented me from getting a conventional education and I became a different human being. Film was both a way to escape and my education.”

Michael Chow

Michael Chow: My mother took me to the cinema all the time. And later on, when I suffered the devastation of abandonment—albeit with a good intention—in the cinema, I escaped the pain. I would go see double features and be there for five hours. I also play poker to escape. And then there’s sleep. Together they reduce the time in life left to suffer.

When I was young, I also suffered from asthma. And those who have suffered from asthma in childhood know it is the most devastating, annoying, uncomfortable suffering in the world, because at least 50% of the time you’re sick…maybe more. And when it stops, life is so fucking wonderful. I’m a collector of everything, including great artists who suffer from asthma–Francis Bacon and Martin Scorsese to name drop a few–and I am part of that club. My asthma prevented me from getting a conventional education and I became a different human being. Film was both a way to escape and my education. I don’t read very much, I think I’ve only read three or four books in my life, so my learning was all from the movies.

You became an actor in movies in your teens. How did that come about?

My sister, Tsai Chin, was the first Chinese student to attend the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, where all the great actors trained. She got a small part in this movie, but there was a big part for a Chinese boy and that’s how I got into it. The movie was called Violent Playground and was directed by Basil Dearden. It took place in Liverpool and starred Stanley Baker and Peter Cushing. I did about 19 films. I was constantly kind of working through the years but never took it seriously. The best part I did was in the movie Hammett about Dashiell Hammett. It was directed by Wim Wenders and produced by Francis Ford Coppola.

What are your three favorite movies?

The Leopard by Luchino Visconti. Lawrence of Arabia. Elia Kazan’s America America. Another one that is very important to me is I Am Cuba by Russian director Mikhail Kalatozov. It’s incredible.

How has cinema affected your approach to life and your art?

It’s affected me tremendously. All my education is through cinema, all the great novels were adapted into movies, otherwise I wouldn’t be educated. That’s one thing. The second way it has influenced me is more in a habitual way of operating my life. I always approach my life as if it were I were scripting a scene. If I was to call you this morning at 10, I would have envisaged the scene and certain things like where I’ll be sitting, I’ll imagine the conversation and so on.

I’m very visual, so every step I take I anticipate in advance as if directing a movie. I’ve written two scripts but they never let me direct. Okay, never mind. And in my life, I control every shot, not just storyboarding. It’s beyond Hitchcock in terms of controlling the content. It’s everything—the sound, the whole scene. The restaurants are also like a movie. I want to see certain kinds of scenes take place in the restaurant so I reverse engineer it. The server has to do that, the maître d’ has to do that, they have to wear this…that kind of detail. It’s a cinematic experience. Everything is a cinematic experience, and I live my life like that.

So, like in painting, do you know how many billions of times I’ve been rejected? But I always have the saying in my mind: “He who laughs last, laughs best.” I can see the plot. I visit all the dealers to show my work. They all laugh and I am humiliated. I persevere and then go on to win the Nobel Prize for painting. The hero triumphs. It’s a cliché. I romanticize and fantasize, but my fantasy becomes real. I make it real. Every breath I take is towards that. I’m relentless.

So, the cinema, theater and the Beijing Opera are all in the background and provide the structure of how you’ve approached your restaurants, your architecture, your art. It all comes out of this performative world.

Yes, well my North Star is my father. He became famous when he was six years old and his greatness was equal to a Beethoven, a Picasso, a Toscanini—one of those giants.

In our previous talks, and in some of the writing I’ve done about you, I’ve emphasized how the movie roles, the architecture, the restaurant, the art you’re doing right now, they’re not separate things. It’s all one big statement and it’s fascinating how it’s all integrated.

Absolutely, there’s no difference. The Chinese already expressed it clearly and very well and nobody listened to it in the West–although Richard Serra did once say on Charlie Rose that architecture is not art. In Chinese, only four things are counted as art—music, poetry, sculpture and painting—because they are beyond craft. Craft seeks for profession, art seeks for expression. So, here comes the expression in Beijing Opera, and some of this was shown in the

documentary, my father’s water sleeves were of a particular length. Not just because they were the most difficult to work with, but also because they were the most beautiful. His beard was also thicker than anybody else’s, making his beard work, blowing through it without the material coming up, more difficult. So, based on that particular philosophy, that’s how I paint. To have freedom you must have form. This is a basic Chinese philosophy.

So, the cinema, theater and the Beijing Opera are all in the background and provide the structure of how you’ve approached your restaurants, your architecture, your art. It all comes out of this performative world.

Yes, well my North Star is my father. He became famous when he was six years old and his greatness was equal to a Beethoven, a Picasso, a Toscanini—one of those giants.

In our previous talks, and in some of the writing I’ve done about you, I’ve emphasized how the movie roles, the architecture, the restaurant, the art you’re doing right now, they’re not separate things. It’s all one big statement and it’s fascinating how it’s all integrated.

Absolutely, there’s no difference. The Chinese already expressed it clearly and very well and nobody listened to it in the West–although Richard Serra did once say on Charlie Rose that architecture is not art. In Chinese, only four things are counted as art—music, poetry, sculpture and painting—because they are beyond craft. Craft seeks for profession, art seeks for expression. So, here comes the expression in Beijing Opera, and some of this was shown in the documentary, my father’s water sleeves were of a particular length. Not just because they were the most difficult to work with, but also because they were the most beautiful. His beard was also thicker than anybody else’s, making his beard work, blowing through it without the material coming up, more difficult. So, based on that particular philosophy, that’s how I paint. To have freedom you must have form. This is a basic Chinese philosophy.

Let’s talk about how your process of painting has changed. When you began painting, the pieces were very ambitious and complex. It took you weeks to make one painting. Now you are more focused on the aesthetic of speed and precision.

With figurative painting, you often hear people say, “I can’t draw, so I can’t paint.” They find it very difficult. With abstract painting, people think you just go like that—throw some paint—and it’s already there. In fact, it’s the most difficult thing to do. You see, one is a technique, which has limitations. Abstract painting is like a recipe. A Rothko is a recipe. You take that kind of turpentine, you take this soda mixed with a kind of flour and marinate it for 30 minutes– it’s a fucking recipe. I’ve been dealing with recipes every night for 54 years, so if I can’t paint, who in the world can?

But there’s another element to your painting that counters the recipe, or complements it, and that’s chance.

It’s all chance, the whole fucking thing is chance. But the chance comes internally. In the Western world, you call it prayer, in the Chinese world we call it Gong Fu. What is Gong Fu? It is repetition. In that repetition you find prayer. In that repetition you find inspiration. In that repetition you find truth. In reality, it’s not really chance because if you keep on doing it, it will come to you.

You’ve built the most inspiring painter’s studio I’ve ever entered. It’s the ideal environment for inspiration, for creation. So what’s your painting practice?

In the Western world, hardly anybody paints in a horizontal position. If you paint a painting on the vertical it drips. So by working on the horizontal you eliminate 99% of possibility. Pollock did it. I never abandon anything. I keep on building. I never use brushes anymore. My tools are the hammer, stretching and burning. These tools are my father’s sleeves, my father’s beard. God made us poor so we have to use everything. And it’s also very complicated because I paint on the reverse. I drip paint 360 degrees. All my corners are mastered, all my edges are mastered. My studio is huge. My scale is universal.

I’ve always connected your painting with the artists who inspired you in your youth: Fontana, Tàpies, Fautrier. You’ve built on that, adding in your feeling for Chinese aesthetics and your familiarity with American action painting.

You just mentioned the best of the best. Before that, you have all the Cubists and Surrealists. You need to know who you’re going to follow and why you are going to follow them and not just who the market tells you to. Sometimes people take centuries to realize how great an artist was. To me, Soutine is superior to Modigliani. Yes, some of his paintings were uneven, but when Soutine is good, nothing is better than him. He can stand next to Picasso. And look at Monet. For years no one appreciated his work. It took Pollock to wake everyone up to him again.

In my life, I control every shot. It’s beyond Hitchcock. It’s everything—the sound, the whole scene. The restaurants are like a movie. I want to see certain kinds of scenes take place so I reverse engineer it.”

Michael Chow

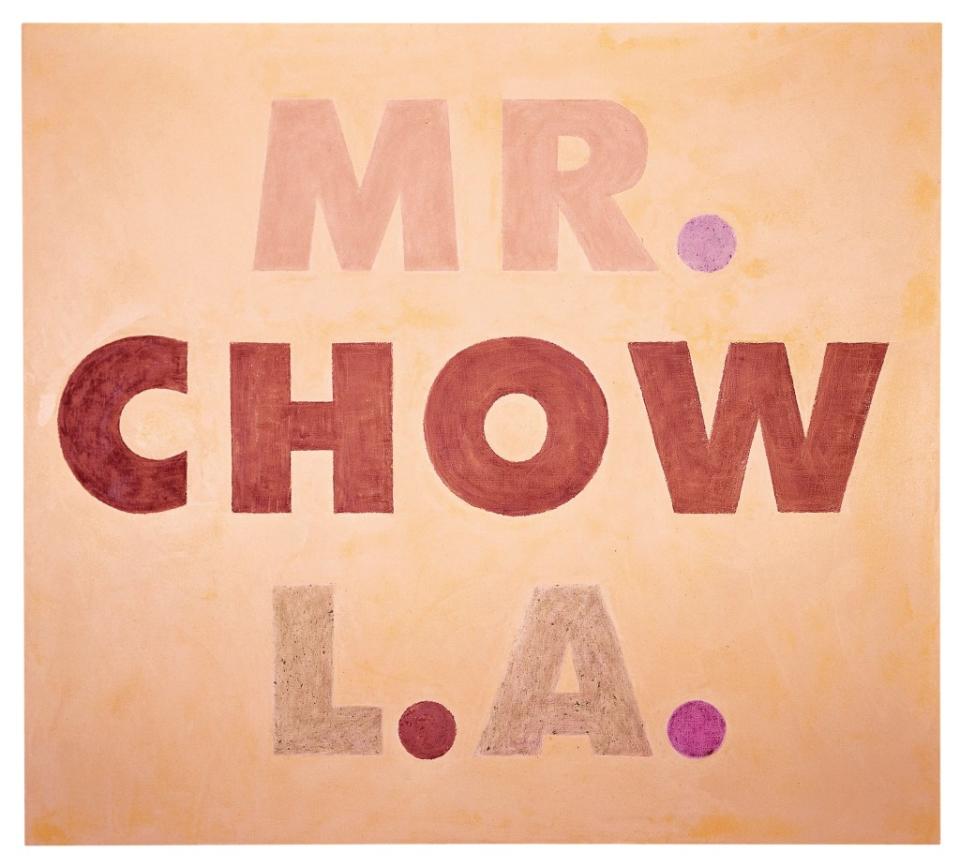

Over the years you have done three specific self-portraits, but your whole project in life is a self-portrait, from the film roles through the whole story with the restaurant to your architecture and now the painting. It’s all a reflection of what’s inside you. It’s all a big self-portrait.

My first self-portrait I did I think when I was 18. I had a temporary job as a janitor in a building in Cadogan Square in London. They put me in the basement and my job was to keep the huge furnace fire going. I was painting an oil painting on an easel, a self-portrait. The problem is I didn’t have a mirror. The only mirror was in the elevator so in the middle of the night, I pressed the button and the elevator door opened and I held it open with my feet so I could paint the self-portrait. From time to time some fucker would call the elevator so the doors would close and it would go up. So that’s the first self-portrait.

The second one I did in 1959. It’s an important year because it’s when Yves Klein did “Leap into the Void.” The sun is setting and I’m wearing all white silk and the Hasselblad is on automatic and I throw a glass of water at it.

A third one, which I did recently, is a giant painting of my penis. I was showing it to the sculptor Paul McCarthy the other day. The reason for this painting is that three years ago the phone rang and it was the doctor saying, “You have prostate cancer but it’s in a very early stage. We have to give you an injection of hormones and radiation treatment.” Before that call, my wife Vanessa had said let’s have a second child because the first child would be lonely. Well, I didn’t want to have a second at the time but then the doctor told me once you have this treatment you’re not going to have a child, it will be impossible so I looked at my wife. We made love, bang! We now have a second child. Since then I’m very conscious of my penis, so I painted this painting, which is basically a giant penis all patched up. This is a self-portrait in my opinion.

After the success of the documentaryaka Mr. Chow, do you have some plans for another film?

After the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s (death), the global celebrations of his work, the exhibitions worldwide and so on, I decided I wanted to do the same thing for my father in 2025, which will be the 50th anniversary of his death. I’m thinking of doing it in China and right now I’m in the middle of it. I have a producer and great cinematographer/director involved, and I’m even thinking of writing to Xi Jinping’s mother because in 1981 or ‘82 she invited me personally to Tiananmen Square because of her respect for my father. In my opinion, looking at China from the West, his work is connected to the best part of China and Chinese culture so I want to celebrate the 50th anniversary of his death.

When I accompanied you to Beijing several years ago for your exhibition at the most important contemporary art museum there, we went out for a few celebratory dinners. At the restaurant, the walls were covered with photographs of your father performing in the Beijing Opera, and it just showed how revered he still is in China today, so that would be a film that would be important for the Chinese audience, the international audience and essential for the Western audience.

This is what we need in this chaotic world. Art is an antidote, culture is a healer. I remember a story you told me about Richard Prince. You said Richard articulated that all art is from the past and you continue it in the future. In other words, part of the artist’s job is to be current. To be current, you have to take all the past and express it to the future to be true to your time.

JEFFREY DEITCH

Prominent art dealer, curator and advisor Jeffrey Deitch is widely recognized for his influential role in the contemporary art world. He served as the director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA), and he is known for his keen eye for emerging talent and innovative programming. Deitch gave us an in-depth Q&A with enigmatic restaurateur and painter, Michael Chow.

The post The Agony and The Ecstasy of Mr. Chow appeared first on TheWrap.