AFI Founder George Stevens Jr.’s Memoir Spans Hollywood and Washington

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The term “Hollywood royalty” gets easily bandied about, but few entertainment figures have a stronger claim to showbiz aristocracy than George Stevens Jr., director, producer, screenwriter, playwright and founder of the American Film Institute and the Kennedy Center Honors, among other distinctions. His father, George Stevens Sr., directed some of the most enduring classics of American cinema, among them A Place in the Sun and The Greatest Story Ever Told. Three of his grandparents were thespians, including silent-film actress Alice Howell, who played opposite Charlie Chaplin. His great-grandmother was Ophelia to Edwin Booth’s Hamlet. Growing up in Toluca Lake, George Jr.’s neighbors included Bing Crosby and Al Jolson. When he fell into the pool as a child, he was saved from drowning by Johnny Weissmuller — Tarzan himself.

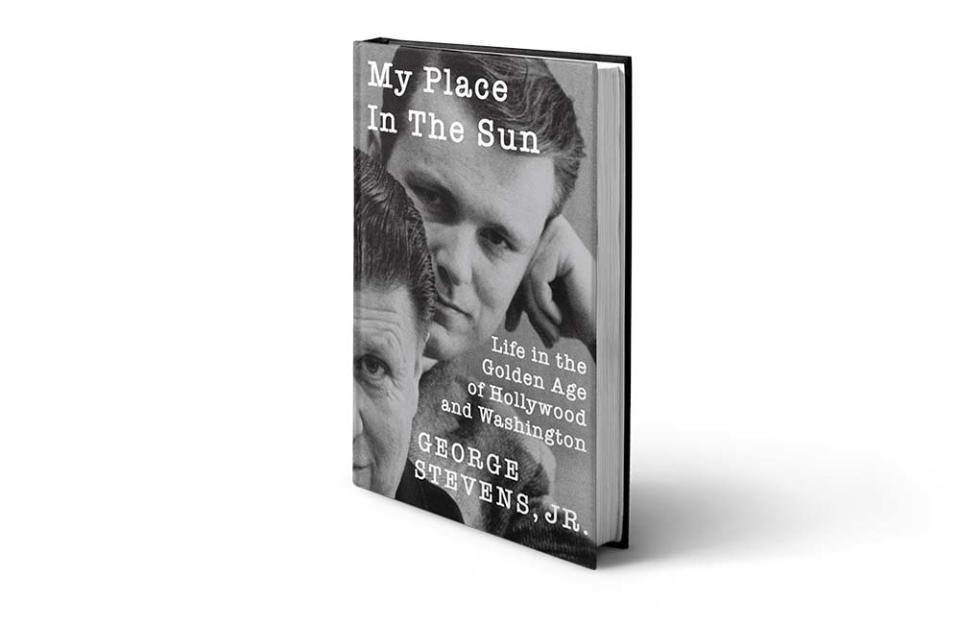

In May, the 90-year-old multihyphenate can add author to his résumé. Stevens’ memoir, My Place in the Sun: Life in the Golden Age of Hollywood and Washington ($35, University of Kentucky Press), recounts his path from Tinseltown to the nation’s capital. The book is replete with anecdotes, including the inauspicious screening for a film called Marines Let’s Go that prompted John F. Kennedy to say, “Tell Jack Warner to go fuck himself,” plus tales of encounters with everyone from Orson Welles and Katharine Hepburn to Barack Obama and Leslie Moonves.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

American Film Institute Sets New Date for AFI Awards After COVID-19 Postponement

'Dune' and 'West Side Story' Among AFI 2021 Film and TV Award Winners

American Film Institute Taps Karen Schwartzman as Senior Director, Innovative Programs

As a young man, Stevens intended to become a sportswriter, but he was lassoed into the family business when his father got him a job reading scripts and books for Paramount. One of the books he plucked out of the pile was the Old West adventure Shane, and he was regularly on the set of his father’s iconic 1953 film adaptation. By his mid-20s, Stevens was directing in his own right, helming episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents and Peter Gunn, among other TV series.

Courtesy of Subject

Stevens was on track to pursue a career in his father’s shadow. “It did occur to me that I was going to devote my life to becoming the second-best film director in my family,” says Stevens. But a 1962 encounter with Edward R. Murrow set him on a different course. The venerable broadcaster, who had left CBS to head up the U.S. Information Agency (USAI), recruited Stevens to elevate the quality of the agency’s films, which endeavored to present U.S. policy in a positive light for a global audience. Stevens moved to D.C. — where he still lives — and produced some 300 short documentaries a year, including 1964’s Oscar-winning Nine From Little Rock, about the integration of an Arkansas high school in 1957.

Beginning under the Kennedy administration, Stevens asked not only what film could do for his country, but also what his country could do for film. He played a pivotal role in getting the U.S. government to recognize and support cinema, which at the time was considered a second-class art form. “I was really surprised by how film was kept to the side,” he said. “It was not too seldom that someone would say, ‘Well, we never go to the movies.’ There was a kind of a snobbism about it. And, of course, I had reason to feel otherwise.” Stevens successfully lobbied for the inclusion of film in the National Endowment for the Arts, created in 1965, and served as founding director of the AFI, beginning the same year. He produced the Kennedy Center Honors from their inception in 1978 until the board (seeking new blood) ousted him in 2014, to the dismay of many in the industry.

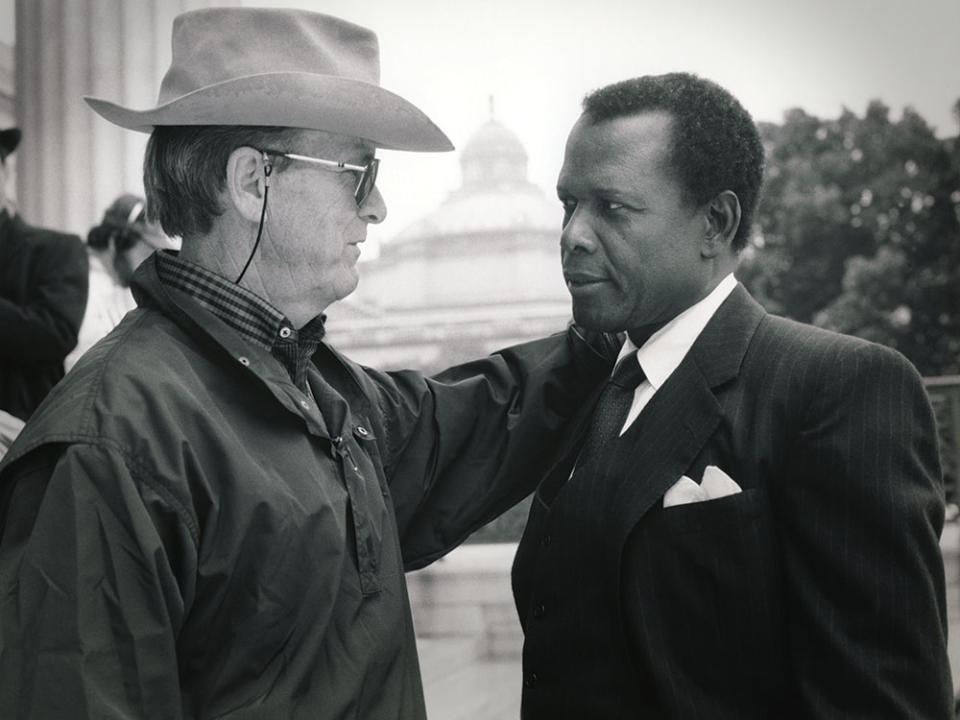

Stevens never left the family business behind entirely. He produced two Emmy-winning miniseries, 1988’s The Murder of Mary Phagan, starring Jack Lemmon, and 1991’s Separate but Equal, with Sidney Poitier. Stevens later wrote the play Thurgood — about the first African American Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall — with Poitier in mind. But when the actor confessed that he had grown too old to memorize the one-man show, Stevens took it to James Earl Jones, who performed the role at the Westport County Playhouse, and then to Laurence Fishburne, who took it to Broadway.

Given that his mother, actress Yvonne Howell, lived to 104, Stevens likely has several more chapters left to write. Recently, Stevens helped Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese bring forth a 4K restoration of his father’s magnum opus, Giant, which premiered in April at the TCM Classic Film Festival in Hollywood.

Having watched Hollywood transform over nine decades, Stevens says he still has faith in the power and longevity of movies despite prevailing headwinds: “My father was never overly admiring of the people who ran studios. And he used to say the only reason the movie business survives is because it’s indestructible.”

Courtesy of Subject

A version of this story first appeared in the May 17 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.