Academy Museum Celebrates Sergei Parajanov’s Centenary With Screening Of Armenian Director’s ‘The Color Of Pomegranates’ Plus Restored Documentary About Him

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

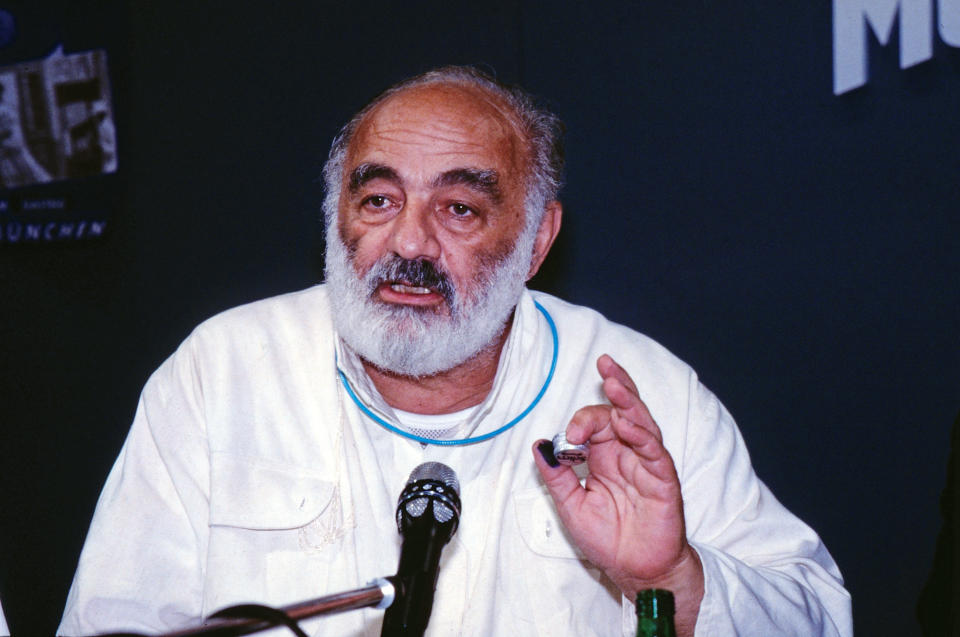

UPDATED with minor clarifications from Martiros Vartanov. The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures is shining a spotlight on one of the most revered filmmakers in cinema history.

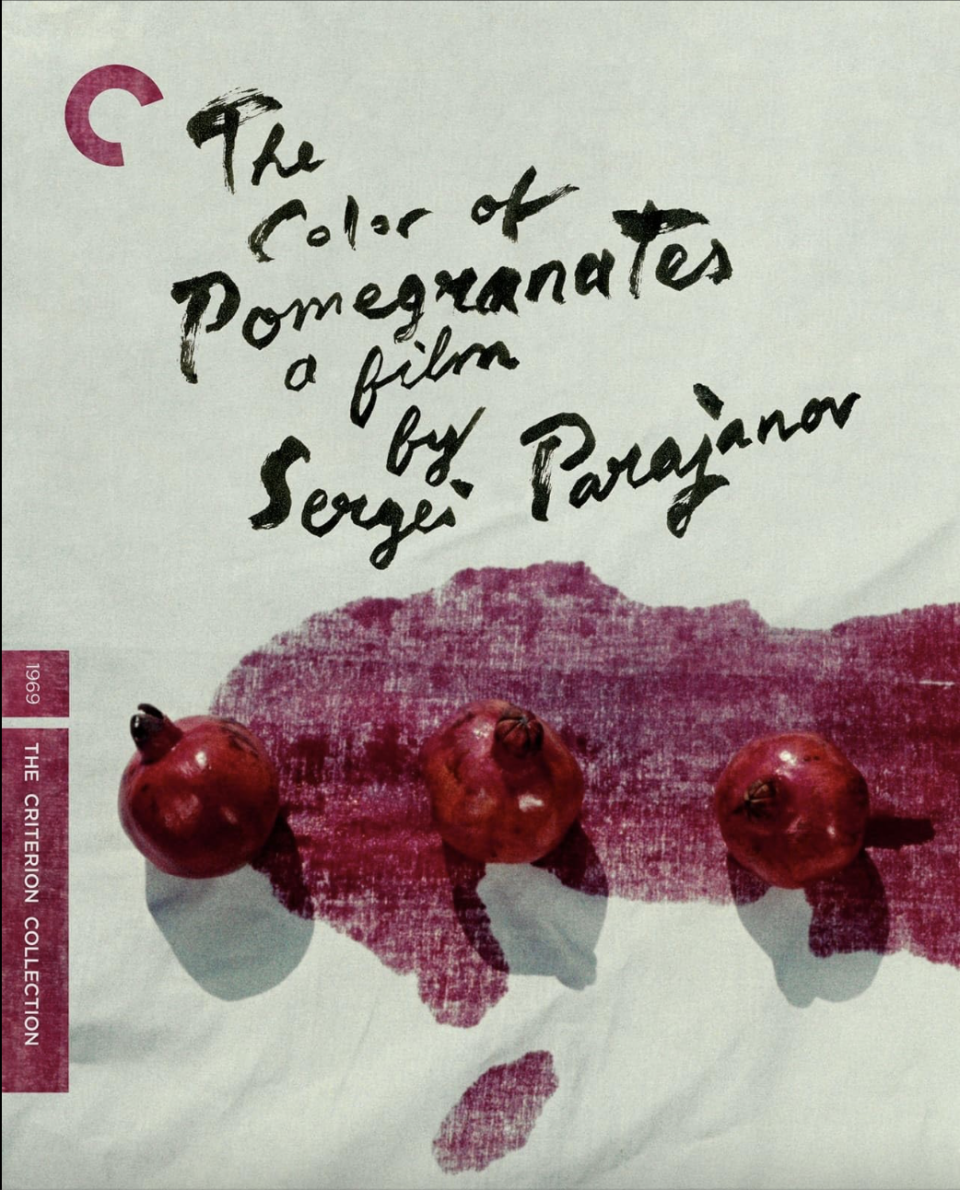

On Friday evening the museum in Los Angeles will screen a restored version of visionary Armenian filmmaker and poet Sergei Parajanov’s 1969 classic The Color of Pomegranates, marking the 100th anniversary of his birth. In addition, the museum is premiering the newly restored Parajanov: The Last Spring, a documentary about Parajanov directed by Soviet-born filmmaker and cinematographer Mikhail Vartanov.

More from Deadline

Michael Cieply: The Academy's Annual Survey Leaves You Wondering - What Does Hollywood Really Think?

Michael Cieply: Why Official Oscar Night Fun Doesn't Come Cheap

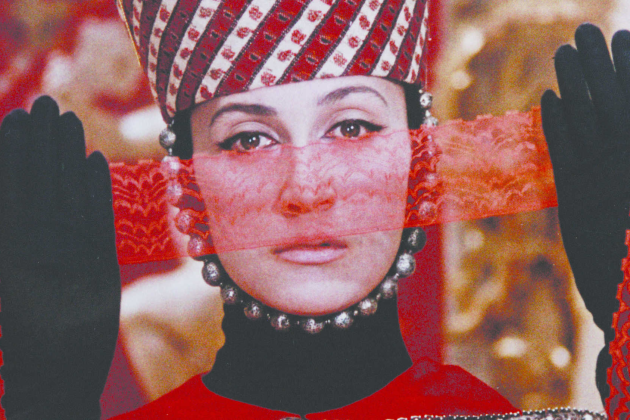

The Color of Pomegranates, a visually metamorphic and hybrid narrative, follows the life of the great 18th century Armenian poet and musician, Sayat Nova. Oscillating between stillness and movement – Pomegranates is a mesmerizing wide-canvas painting on film and has been hailed as one of the greatest movies of all time in various polls conducted by Movieline, Time Out, and the British Film Institute’s magazine, Sight and Sound.

Vartanov’s documentary Parajanov: The Last Spring (1992), is a touching farewell tribute to his close friend and artistic collaborator. Filmed during the collapse of the Soviet Union, when Armenia was in a state of war and devoid of infrastructure and resources, Vartanov edited the film under candlelight. He incorporates stunning, wordless montages and documents Parajanov’s final days, preserving the original camera negative of Parajanov’s unfinished autobiographical film, The Confession.

Parajanov and Vartanov were both politically outspoken and controversial figures during the Soviet regime of the 1970s. Parajanov was imprisoned by Soviet authorities in Ukraine, and Vartanov was blacklisted for his film The Color of Armenian Land (1969). The dual maestros’ artistry has been celebrated by some of modern cinema’s great filmmakers including Federico Fellini, Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Jean Luc Goddard, and Jim Jarmusch.

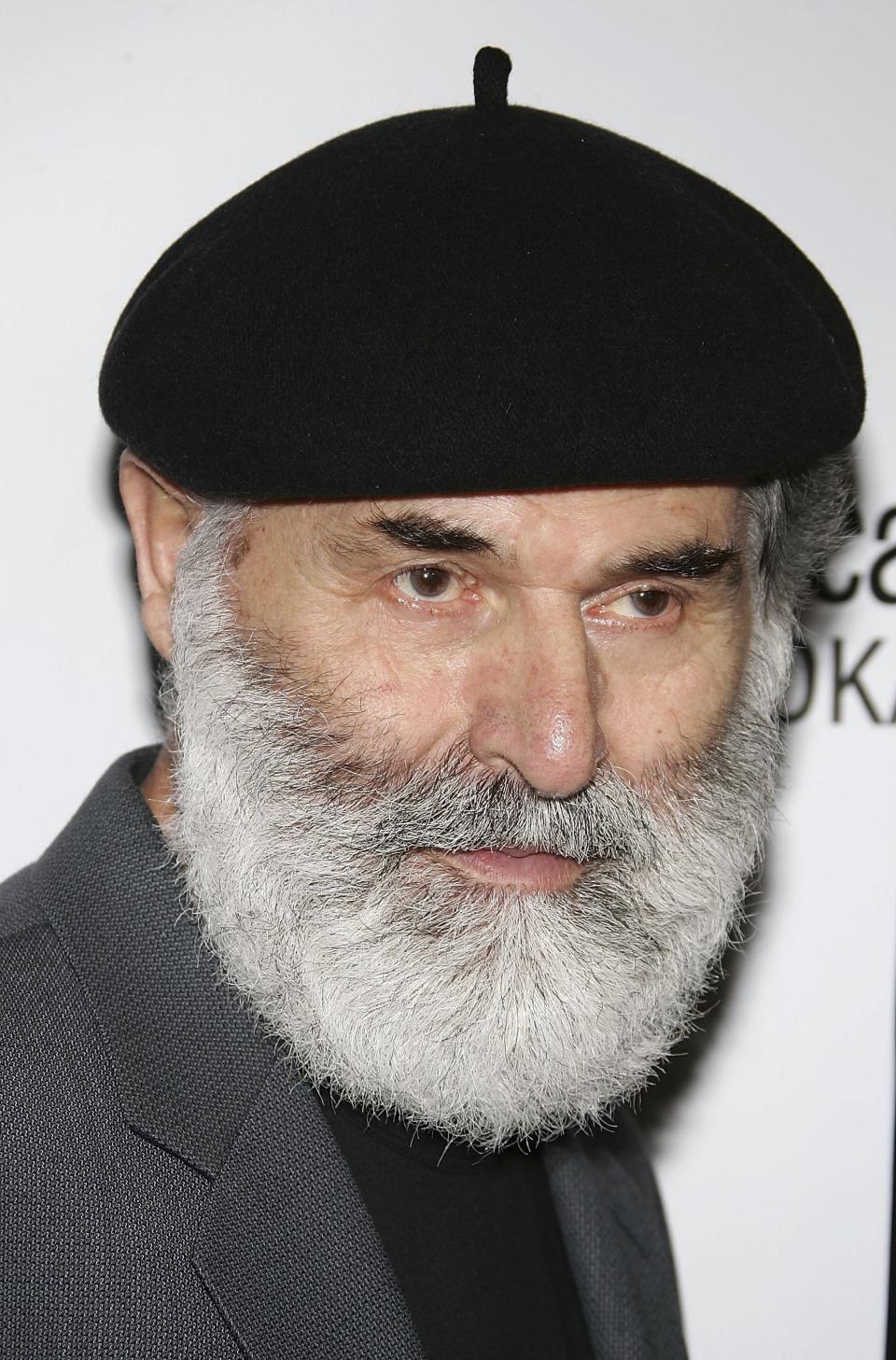

Martiros M. Vartanov, founder of the Parajanov-Vartanov Institute and the son of Mikhail Vartanov, worked with Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation on the restoration of The Color of Pomegranates, and with the UCLA Film and Television Archive on the restoration of Parajanov: The Last Spring, with support from Francis Ford Coppola and Grammy-winning rock band System of a Down.

DEADLINE: The restoration work of Sergei Parajanov’s The Color of Pomegranates is extremely detailed, further enhancing the film’s visual mastery. What are the elements of the film that make it unique and important to preserve?

Martiros Vartanov: From the historical point of view, it’s very important [to preserve films] because there are millions of films and some were highlighted as very important works. And just like paintings at great museums, they have to be preserved for history. In The Color of Pomegranates, as my father Mikhail Vartanov said, Parajanov invented a revolutionary film language, which was ahead of its time. And I think we’re now just catching up to how ahead of its time it was because of its influence. It’s continuing to spread, inspiring amazing musicians and artists –Madonna, Lady Gaga, and many others. We all know that it’s a physical medium, and [film] deteriorates, so it has to be properly preserved, then has to be restored. It’s very difficult now to show the film in the original format, which is 35 mm. That’s why it’s great that organizations like The Academy and many others preserve the facilities to project the films in the original forms. When I had the honor of presenting Martin Scorsese with the Parajanov-Vartanov Institute Award in New York for the restoration of The Color Pomegranates, after it premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, I told him, “Thank you so much, because I’ve been watching this film since childhood so many times, but I feels like I’ve seen it for the first time.”

DEADLINE: What makes the documentary Parajanov: The Last Spring, made by your father, Mikhail Vartanov, groundbreaking and why is it still remembered and treasured today?

MV: Parajanov: The Last Spring is very important because it was created during the collapse of the Soviet Union when Armenia was at war. This film, which is about an hour long, has only about 10 minutes of voiceover. So typically, when you think of a documentary — at least these days, you’re used to watching documentaries on television where everything is shown and explained – this film will seem to you like almost a non-documentary. It’s from a different world. And I think critics who have seen this film have appreciated it… The L.A. Times wrote that “it’s exquisitely interweaved to evoke the very soul of the genius.” It’s true because most of the film shows you and does not tell you what’s going on. And it takes, as they often say, more active participation in the process of watching. Martin Scorsese wrote wonderful words about it. Jim Jarmusch said that “Mikhail Vartanov’s fascinating document, Parajanov: The Last Spring is an important and alluring film for all those who love the form of cinema.” Tonino Guerra, who is the legendary screenwriter of [Federico] Fellini and [Michelangelo] Antonioni masterpieces, said, “the film excited and filled me with strength.” And so it’s hard to say why, but I am extremely moved when great masters like Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Jim Jarmusch say wonderful words about it.

DEADLINE: What did the restoration process entail on The Color of Pomegranates and Parajanov: The Last Spring?

MV: I was involved in both of these restorations, and it was a very interesting, fascinating process. The Color of Pomegranates, one of the most important things is that the original negative of the film was recut by the Soviet censors, and that original negative is preserved in Russia, whereas only a copy of the original Armenian [version] is preserved in Armenia. And so it was important for the lab, L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna, Italy, to reconstruct the original Armenian version from the negative that was in Russia and copy of a dupe negative that was in Armenia. The original negative was scanned in Russia as well as the dupe negative was flown to Italy to be scanned. They reconstructed the film in that way. And of course, because some of the scenes are only available in the Armenian part of the film from a dupe negative, it was a lot of hard work to try and get them to match and look as good as they possibly can. And with Parajanov: The Last Spring, [the film was made] under unimaginable conditions. We had an hour daily quota of electricity and water, no gas, no heat, no phones, and no transportation. This is how the film was created under these crazy conditions. For example, when you are developing and printing the film, you [need] the right temperature for the water, for the chemicals. And all of that was not available. And so it was just printed in the best way they could manage under insanely difficult conditions. So we had to be very careful. When we’re restoring with the UCLA Film and Television archive to get everything right, we tried to bring back to life those things that were basically sort of erased. Both of these films were scanned and restored in 4K. Ultimately, I think the goal is to present them in the best possible way through modern technology… I’m very happy that [these films] will now have a new life.

Deadline: For what alleged crime was Sergei Parajanov imprisoned during the Soviet era?

MV: I’m glad you asked it because there are sometimes misconceptions about this. Without a doubt, Parajanov was imprisoned for his outspoken criticism of the Soviet regime, particularly after the speech he gave in Minsk, Belarus (Belarussia) in the 1970s. But also because the success of his Ukrainian masterpiece, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, had prompted some nationalistic movements in Ukraine because Russia was suppressing all the national movements in all the republics, [and] in Ukraine also. So what they understood is that he was a very free person in a very unfree society, and that he was very influential. People were learning from him, being influenced by him. So they imprisoned him on a long list of charges, including homosexuality, trafficking in religious icons, and a whole list of other things because they needed to ensure that they could put him away. In fact, in Parajanov: The Last Spring, my father tells how just towards the end of his five-year prison term, they tried to fabricate another case to add another five years, not to let him out. It was thanks to [author and socialite] Lilya Brik who asked French poet Louis Aragon to petition for Parajanov’s release, during a meeting that Aragon had with Soviet leader Brezhnev. It was this particular intervention that finally was the reason why they let him out.

Deadline: The Color of Pomegranates highlights the life of Armenian poet and musician Sayat Nova. Can you tell us more about him and why the Soviet sensors changed the title from Sayat Nova to The Color of Pomegranates?

MV: [The Color of Pomegranates] is loosely about Sayat Nova. He was an inspirational figure for Parajanov. I think I remember he inscribed on the screenplay of Sayat Nova and said, “I am Sayat Nova” — something along those lines. Sayat Nova wrote in several languages and was a beloved figure in the region. And it’s very similar to how Parajanov is, because he also created masterpieces for Armenia, Georgia, Ukraine. But what happened was the Soviets basically needed a film for the anniversary of Sayat Nova. Obviously, they expected a film that conformed to the socialist realism – the sanctioned style there. They got something completely different. So they removed many references to Sayat Nova. In fact, at the end of the film, you can see one of the actors saying the words “Sayat Nova,” but you don’t hear the words because they were cut from the film.

Deadline: Your father, Mikhail Vartanov, had a close friendship with Sergei Parajanov. Why was the relationship between them so important?

MV: It’s very interesting and fascinating, moving stuff. When Parajanov was in prison in [Soviet-controlled] Ukraine, my father was one of the only friends who wasn’t afraid to correspond with him. They wrote many letters to each other. In a letter my dad wrote to him, he said, “I know you have come into this world to counterbalance mediocrity and swinishness, and when I think of you there in prison, I don’t want to live.” And Parajanov responded to him and said, “My dear friend, perhaps you’re the only friend who compels me to live.” So this exchange shows you what their friendship was like. He [Parajanov] was only allowed two letters per month… It shows you how close and important their relationship was.

Deadline: What does it mean for you to have both films screen at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures?

MV: It’s the birth centennial of Parajanov, so I’m very grateful to The Academy and UCLA for presenting this. It’s very meaningful for me because when The Color of Pomegranates was restored, The Academy invited me to present the film, and it was the U.S. premiere. Then to come back and present the world premiere of Parajanov: The Last Spring is very meaningful. And now they’re showing together. This union of these two filmmakers is part of my life… It’s very moving and important. But the fact that it’s the Academy Museum, I’m really delighted and grateful to everyone there and UCLA.

Best of Deadline

Hollywood & Media Deaths In 2024: Photo Gallery & Obituaries

2024-25 Awards Season Calendar - Dates For Oscars, Tonys, Guilds, BAFTAs, Spirits & More

2024 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.