Aaron Sorkin's Silicon Valley

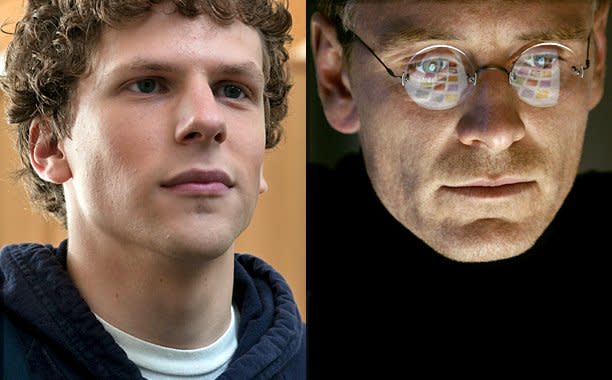

Aaron Sorkin doesn’t understand Silicon Valley. Counterargument: Who does? You can’t even dig deep for accurate depictions onscreen of the Bay Area tech industry. Besides The Social Network and Steve Jobs, the only major feature-film presentation of Silicon Valley recently was Jobs, a vanity-project biopic starring Ashton Kutcher.

That film gains resonance only when you remember that point a half-decade ago, when Kutcher was a weird nexus point between showbiz SoCal and tech biz NorCal. Kutcher was an early social media adopter who lived half his first marriage on Twitter. He invested in various tech companies, and then used Two and a Half Men to blipvert those tech companies.

So Jobs is fascinating as an advertisement for the idea of Ashton Kutcher, Entrepreneur. It’s not a movie; it’s an item on a resumé. Kutcher looks much more like Steve Jobs than Michael Fassbender, which is the only thing besides “It’s terrible” you can say about the movie. Jobs adds nothing to the world. It is hollow. In Act 2 of the new Steve Jobs, Sorkin vastly dramatizes the reveal of NeXT, Job’s post- and pre-Apple project. NeXT is a beautiful black hollow cube, a computer without an operating system, clothes without an emperor. Steve Jobs makes the truth about NeXT into a cathartic twist-reveal: Thank God, Steve Had A Plan The Whole Time.

It’s something the hagiographies don’t tend to print: The idea that part of being a “visionary” is being a self-promotional huckster narcissistic enough to self-identify as a visionary. That’s an idea underlying Startup.com, a forgotten but brilliant portrait of GovWorks, a forgotten and terrible company from the boom-bubble millennium turn. The surreality of Startup.com reads as satire, but only in the Kubrickian end-of-civilization sense: To laugh, you need to get past crying. One second, the founders are burning through sixty million investment dollars: Twice what it cost to make Steve Jobs, in 1999 dollars. The next second, they’re getting introduced by still-President Bill Clinton.

Startup.com doesn’t actually spend much time in Silicon Valley, but you can recognize it as a retroactive sibling to HBO’s Silicon Valley, which both deconstructs and burnishes all the myths about start-up life. Silicon Valley is a comedy, and occasionally a satire. It speaks truth to power, but it will also happily welcome power onscreen for a cameo. This could be a bit for authenticity — although anyone who thinks real-person cameos connote reality is the last person on Earth who never watched Entourage. It also feels like a defense mechanism: A way to hold off all those “What [whatever] doesn’t get about Silicon Valley” thinkpieces that tend to pop up whenever someone tries capturing the truth about the tech industry in some fictional form.

Which, coincidentally, is why I can’t wait for the inevitable overreaction to The Circle, next year’s adaptation of the Dave Eggers novel. The Circle takes place in a company that isn’t merely a fictionalized version of Google, Amazon, or Facebook. The Circle‘s company has consumed Google and Amazon and Facebook into a single utopian-monopolistic vision of Silicon Valley-hood. Full disclosure: I used to work for Eggers. Fuller disclosure: I haven’t read the book. But the time is never wrong to be skeptical about massive corporations. Just because there are college kids who never lived without Facebook doesn’t make Facebook a good thing. (Sixty years later, who loves the bomb?)

Of course, The Circle comes from a grander cinematic tradition of tech paranoia; its alarmism is the sober literary cousin to CSI: Cyber, our new national nightmare of predatory cloud-demons hacking your baby’s Bluetooth pacifiers. Through the late ’90s, anything “tech” onscreen vibed nefarious: An Orwellian corpo-political omnipresence hunting movie stars like Sandra Bullock and Will Smith. The lone counterexample came in 1999, when TNT delivered Pirates of Silicon Valley. Pirates is very “TV Movie” TV movie that leans hard on narration and assumes audience familiarity with a specific long-gone context where the Bill Gates death-cult of personality was the superior force versus the Steve Jobs god-cult of personality. It’s overrun with clichés, and anyone who’s not a main character talks like a New Yorker in an old superhero comic book, spouting opinionated on-the-nose dialogue. (Sample overheard dialogue from an angry-mob scene: “Microsoft is gonna ruin Apple! You can’t trust ’em!)

But the smallscreen cheapness of Pirates has aged well: It is the cheapness of blocky NES graphics and floppy discs and chunky pre-stylish computers. It’s in a hyper-specific subgenre — this and Rush, basically — where a biopic has two famous-enemy subjects who both come off as great heroes but terrible people. Pirates begins with Noah Wyle-as-Jobs talking to the screen, speaking to the audience, kind of:

Don’t want you to think of this as just a film – some process of converting electrons and magnetic impulses into shapes and figures and sounds. No. Listen to me. We’re here to make a dent in the universe. Otherwise, why even be here? We’re creating a completely new consciousness, like an artist or poet. That’s how you have to think of this. We’re rewriting the history of human thought with what we’re doing.

This is a classic bit of Jobs-inflected hucksterism, complete with that “dent in the universe” line that has become Jobs’ de facto catchphrase. The camera pulls back, and we see that Jobs is on a film set: They’re making the famous “1984” advertisement. He’s speaking to Ridley Scott, and Scott can’t be bothered. “Well, Steven,” he says, “at the moment, I’m a touch more worried about getting light on the actors.” (ASIDE: This is a throwaway line that also could be the finest critique of Ridley Scott captured on film. When you watch The Martian and the story gets boring, you can always admire how perfectly the light sweeps across the actors’ faces. END OF ASIDE.)

Pirates cuts immediately to the 1997 Macworld Expo, where an older, mildly chastened Jobs welcomes Bill Gates. Gates appears on a big screen: He is become Big Brother from “1984.” The visual symmetry is cheap, but effective. It made more sense back then, in the old Evil Empire days. Times change and history refuses to make any easy arguments: Gates spent the 2000s giving billions to the poor; Jobs spent the 2000s making billions off their labor.

——————————————————

Starting with “1984” is an easy decision, but also a profound one. “1984” is either the greatest or most overrated commercial in history. It was always fruitless to dig too deep into any of the ideas underpinning that commercial; using George Orwell to sell anything is a sin even Orwell could laugh about. And it’s especially fruitless to excavate “1984” now, as I type on an Apple computer with an Apple phone in my pocket. (Also: When did we start caring about commercials?)

But Sorkin begins Steve Jobs two days after “1984” airs during that year’s Super Bowl. It is the inciting incident: Everyone saw that ad; now, we understand, everyone will be watching this product launch. “1984” isn’t an actual product, of course. It’s just showbiz. But Sorkin’s vision of Steve Jobs is showbiz, too. Steve Jobs is about the occasional moments in a lifetime when the CEO of a technology company became an entertainer: A behind-the-scenes story that fits right alongside Sports Night and The Newsroom, Studio 60 and even maybe the CJ scenes in The West Wing. Sorkin has always been a playwright, and you can feel how much he must love the world backstage: Those madcap moments before a show when the clock ticks toward the raising of the curtain.

Sorkin’s version of Jobs gets to be the ultimate Sorkin subject. In stage terms, he’s the writer, the director, and the lead actor. He’s applying makeup in his dressing room; he’s commanding that the tech crew follow his script. Early on, we see him freak out about lighting — shades of Pirates‘ Ridley Scott. In one of the movie’s couple hundred Big Lines, Jobs compares himself to a conductor of an orchestra. Like so many things Jobs says in the movie, it’s a line that’s supposed to be praising with faint damns. (“Sure, he’s an ass,” the movie is telling us, “But also, he’s right.) Nobody ever asks the obvious question: Who the hell wants to watch a conductor for two hours?

This is the Hollywood version of Jobs, in every sense of the word. It’s almost too easy to argue against this depiction of the man. Not because it’s unflattering. Far from it. Someone might tell Fassbender’s Jobs that his daughter is more important than his work; but in the movie, Jobs gets to accept that advice, and reveal that maybe he always loved his daughter, and receive absolution, and also keep on being Steve Jobs. It portrays his sins only to sanctify them.

The bigger issue with the movie, and the issue some people had with The Social Network, is how it divorces the drama of Silicon Valley from the work of Silicon Valley. Facebook is a social network with the stated goal of connecting the whole world; in the least convincing but most sticky interpretation of The Social Network, it was launched by douchebags to get chicks. Steve Jobs fits a Greatest Hits album of Steve Jobs moments into a two-hour walk-and-talk, but this version of Steve Jobs only ever seems to talk to people about Steve Jobs.

The best scenes in the movie are all the Wozniak interactions. The stuntcasting helps here: We’re prepared for Rogen to play a goof and Fassbender to play a gallant, so it’s a kick to see that Rogen’s Wozniak is the smart passionate humanist and Fassbender’s Jobs is a hyperbolic catchphrase-spouter. And the film has the clearest idea of a point when Wozniak walks onscreen. The movie can only frame their dynamic in obvious pop culture terms — Why is Wozniak the Ringo to Jobs’ John Lennon? — but Wozniak’s dialogue is a chorus familiar to anyone who has followed Steve Jobs long enough to know why some people don’t like him. He doesn’t write code. He’s not an engineer. He’s not a designer. Wozniak was responsible for everything they didn’t steal from Xerox. So: Why does everyone call Steve Jobs a genius?

The movie never explicitly answers that question; in the end, it’s more interested in Steve Jobs as Father than Steve Jobs as Whatever Interests You About Steve Jobs. Implicitly, Steve Jobs makes the argument that Jobs was less a genius inventor than a genius showman. From anyone else, this would come off as a critique. But no one believes more passionately in the moral rightness of show business — in the ability of sportscasters, comedy writers, and Keith Olbermann to genuinely change the world — than Sorkin. Remember: This is the same guy who wrote A Few Good Men, the movie where Tom Cruise coaxes a murder confession out of Jack Nicholson using the power of oratory.

So, in Sorkin’s view, Steve Jobs was not a technological visionary. He was something much, much better: He was an entertainer. This is a hilariously reductive vision of Jobs — but it also captures something ineffable, about Silicon Valley, the culture it has created, and the weird way those of us on the outside look on admiringly. Jobs had a “reality distortion field,” the myths say: The ability to convince anyone of anything, using charisma or hyperbole or marketing.

The idea of a “reality distortion field” should be negative: It most readily euphemizes to “lying.” (Next to Jobs, the name most often linked to the phrase “reality distortion field” is Bill Clinton.) But the movie — and the culture at large — tends to marvel at the idea of a man who could bend the world, recreate it in his own image, or just generally put a him-shaped dent in the universe. Steve Jobs makes some of the obvious jokes — “Think Different” should be “Think Differently,” and why the hell is Einstein in an Apple ad? — but it never takes the step you want it to take. It marvels at Jobs’ showmanship. It doesn’t question it — and it doesn’t question what kind of culture could lionize it. It’s less interested in the man who created the iPod than the man who made those cool iPod commercials.

————————————————————

Fiction is a reality distortion field, too, and Sorkin has never let the truth stand in the way of a good story. But with The Social Network, he carved the twisted backstory of Facebook into a corrosive vision of Silicon Valley success. There are so many things about Social Network that don’t ring true. There’s the idea of Mark Zuckerberg as a social outsider who hates the old-world WASP elites but only because he so badly wants to be an old-world WASP elite. There’s the Rosebud-y extrapolation of an ex-girlfriend into the Wound that defined Zuckerberg’s whole life. There’s the moment in the movie where we know that we’re at Stanford because a coed played by Dakota Johnson wears panties with “Stanford” stamped across her butt.

Director David Fincher can’t help but make everything look much cooler than it ever could be. And even though Sorkin has always fancied himself a writer of Big Ideas, he never lets his characters postulate toward the deeper meaning of what they are doing, or why. But there’s a hip nihilism at the core of The Social Network that feels interesting specifically because it’s so disparate from most popular conceptions of Silicon Valley. By sidestepping all the possibly philosophical implications about Facebook, Sorkin reduces an almost abstract notion of Connectivity into an economic endeavor of pure brute-force capitalism. Facebook can be an idea of human interaction; in The Social Network, Facebook is lawsuits.

There’s one character in The Social Network who reminds you a lot of Fassbender’s Jobs. It’s not Zuckerberg: It’s Sean Parker, incarnated by Justin Timberlake as a salesman peddling billion-dollar snake oil. I’m not sure The Social Network‘s Parker is anymore factual than Steve Jobs’ Jobs. But that movie’s vision of Parker — unencumbered by messianic pretensions, or the urge to debunk those pretensions — feels much more three-dimensional. He’s a terrible person, but also essential to Facebook’s success; he’s a self-destructive and corrosive influence, but he’s also attractive, and fun. He’s like the Gordon Gekko of Silicon Valley. (Jobs in Steve Jobs is also like Gordon Gekko, but he’s the Wall Street 2 version where in the end he cares the most about his daughter.)

There are blessedly few recognizable Sorkin archetypes in The Social Network. Indeed, the one character in the movie who talks the most like a Sorkin hero is Rooney Mara, the mostly absent girlfriend who doesn’t think too much about Zuckerberg or his weird website. (And even she winds up joining Facebook!) You don’t get the vibe that Sorkin particularly respects any of the characters — or maybe that’s director David Fincher, who splashes cold ice water all over the usual fiery Sorkin patter. (By comparison, with Steve Jobs, fabulist Danny Boyle just pours on the lighter fluid.) For once in a Sorkin script, no one is motivated by a higher cause: It’s for women; it’s for money; it’s to be cool; it’s for revenge.

Again, this maybe doesn’t necessarily have much to do with the actuality of Silicon Valley. It sounds a bit like Hollywood, actually. And maybe that’s the smartest thing Sorkin brings to these movies: The idea that Silicon Valley and Hollywood are two sides of the same coin, two reality distortion fields separated only by geography and varying degrees of self-importance. In Sports Night, The West Wing, Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, and The Newsroom, he constantly demanded you to believe that his characters were changing the world. That kind of made sense in The West Wing and made no sense in the last couple TV shows. (Who the hell ever liked cable news?)

But the people who populate Aaron Sorkin’s TV shows would find kindred spirits in Silicon Valley, where the most inane new app comes gilded with universe-denting marketing materials. You watch Steve Jobs and you have to conclude that Sorkin admires that reality distortion field: That the whole movie is a love letter between showmen, game recognizing game. This isn’t what Steve Jobs is supposed to be about — but it is.

——————————————————

Sorkin doesn’t like the Internet: This is the easiest thing to say about Sorkin now, an argument buttressed by his work and his frequent public statements. He once told Stephen Colbert: “I do think that socializing on the Internet is to socializing what reality TV is to reality.” Like a lot of Sorkin’s writing, that’s a snappy line that is specifically designed to end an argument before anyone can ask what he actually means. Is he saying that socializing on the Internet is fake, or that it’s a more extreme version of actual socializing? His point seems to be a lack of authenticity — but he’s the guy who keeps turning complex true stories into two-hour Citizen Kane riffs.

Sorkin’s distaste for the Internet gets held up as a counterargument against him writing these movies. (How can somebody who doesn’t understand Facebook write about the creator of Facebook?) Maybe it’s just because I’m old enough now to barely understand SnapChat, but I don’t mind Sorkin’s man-from-Mars approach. He has pinpointed a wonderful idea of Silicon Valley as a society of bullshit artistry: Show business, except instead of movies and TV shows, Steve Jobs got to make a whole world.

Have you ever heard of Start-Ups: Silicon Valley? Probably not: The Bravo reality series ran for ran for eight episodes in late 2012. It was despised by anyone who bothered to watch it, and nobody really did. The show follows young entrepreneurs living in the San Francisco-to-Palo Alto corridor. In the first episode, the focal characters are white and cute, filmed shirtless in their undies. Like, sample line: “When I joined Ampush, they didn’t know that I was an NBA dancer for the Milwaukee Bucks.” Another sample line: “I better be arrested, laid, or blacked out somewhere by 2 AM.” Another sample line: “Living at the Four Seasons is like living in a bubble. And I love this bubble.” People have jobs like “videoblogger,” “lifecaster,” and “advisor for star-ups.” Actually, that’s just one person with all those jobs.

Start-Ups badly wanted to invest itself in the central universe-denting ideology of Silicon Valley. “The future of the world is in our hands,” says some dumb beautiful person, “And we’re not sitting back and letting it pass by.” We’re told geeks are the new rockstars, that there’s a spirit of “f– you disruption” underlying Silicon Valley. Someone says: “We’re the kind of generation coming up who want to really change the world.” (Finally: A generation that wants to change the world!)

Now, making fun of a reality show is like making fun of a commercial: Trying to stop the virus just spreads the virus further. In an interview with Vanity Fair, executive producer/sister-of-Mark Randi Zuckerberg said “People need to realize that this is a reality show, not a documentary,” which is an exciting new way of saying “This show is a hot pile of trendy buzzword crap.”

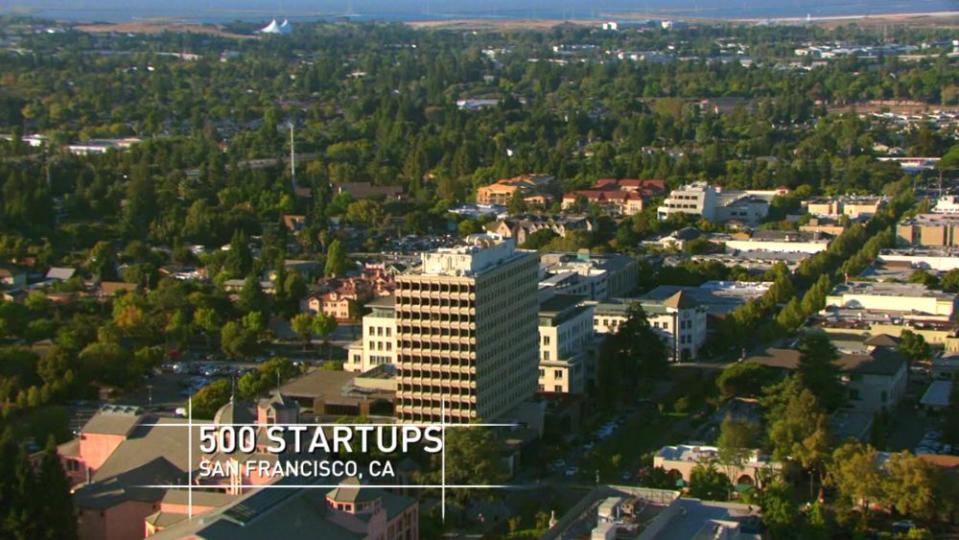

Like most reality shows, Start-Ups is only interesting on accident. But it is interesting. The show captures something about the psychoscape of Silicon Valley: The weird mixture of youthful vanity, the elevation of naivete, the central idea that it is possible to change the world and that “changing the world” should be worth a billion dollars at least. (A throwaway line: “We’re trying to solve the obesity problem in America.”) There’s a moment in the first episode when two entrepreneurs visit the Mountain Bay Plaza Building on Castro Street in Mountain View. It’s the tallest building in Mountain View and thus maybe the only recognizable building in Mountain View.

Here’s how it gets introduced onscreen:

But that geographic distortion is nothing new. San Francisco isn’t Silicon Valley, unless it is, and Silicon Valley is totally different from San Francisco, unless it isn’t. In that screenshot, way in the distance, you can see the twin tent peaks of the Shoreline Amphitheatre, which is about 35 miles south and east of the physical definition of San Francisco. One of the best shows I ever saw there was Depeche Mode back in August 2001, when Dave Gahan’s crowdwork mostly consisted of saying “How’s it going, San Francisco!” between songs.

Start-Ups takes that hazy Bay Area geography as an operating aesthetic. It’s also hilariously and offensively deracinated — there are constantly nonwhite people on the side of the frame, unmiked roommates and co-workers who seem way more interesting than the sex-idiot leads. A kind of cultural gentrification ripples through Start-Ups, a sense that Silicon Valley has become a frat party for the privileged self-righteous. It’s not Silicon Valley, but it could be the dark side of Silicon Valley.

The most interesting character in Start-Ups is the woman who lives in the Four Seasons, the Lifecaster/Vlogger/Advisor. She’s living there for free in return for doing “Social Media/Marketing” work that we never see her do. She tells us that she gets paid ten thousand dollars per branded tweet. We see her interview some people on camera for something. She tells us: “On a typical day, it takes me about two hours to get ready for work.” She is very attractive, a fact the show demands you to notice when she wears this to a toga party. She is precisely the kind of character we would get angry at Aaron Sorkin for inventing, a straw-man compilation of all the least defensible ideas about the Internet and Millennials and People Who Don’t Remember Walter Cronkite.

The lifecaster is Sarah Austin. Even just writing her name feels like an advertisement — and the most unsettling part of Start-Ups is how aware you are that everyone onscreen is selling themselves and their company, that the mere fact of them being on Bravo is more important than any stupid thing the cameras catch them doing. (The whole show is just Ashton Kutcher and his Two and a Half Men decals; the whole cast might as well wear T-shirts that say “BUY ME.”) But I keep pondering her best and dumbest scene in the premiere of Start-Ups. She’s currently in a feud with another vaguely-defined vlogger/entrepreneur/blonde human. This other person had loaned her money for a flight to South by Southwest. (What about those ten-thousand-dollar tweets?)

Once there, though, Sarah got her friend in trouble. The friend was running some kind of event — jeesh, what do these people do? — and Sarah thought she wasn’t doing a good enough job. So she emailed the friend, and all of her bosses, to complain. It’s never clear why this happened, and when challenged about it, Sarah can’t really offer an explanation. Or rather, she offers the ultimate explanation:

This is the kind of thing Sorkin’s Steve Jobs might say, if Sorkin’s Jobs didn’t always speak in verbose parable-tangents. The overwhelming narcissism and beyond-existential ambitions of Start-Ups: Silicon Valley are the core of Sorkin’s interpretation of Jobs. I’m not sure the real Steve Jobs agonized so much about being Time’s Man of the Year — but Sarah doesn’t waste a moment mentioning that she was one some magazine or other’s “30 Under 30” power list. And I’m not sure Start-Ups is an accurate portrayal of Silicon Valley. Someone, someday, will make a movie or a TV show that takes the ambitions and surreal unreality of the tech world seriously. (Early in the life cycle of Facebook, Steve Jobs told Mark Zuckerberg that the way to reconnect with his original mission statement was to travel to a specific Temple in India: Imagine what Terrence Malick could do with that information, especially if you extrapolate that somehow there was an acid trip involved.)

But Start-Ups: Silicon Valley is set in the Silicon Valley that Sorkin has conjured up in his two scripts: A place where the most admirable trait isn’t authenticity, but a breathtaking lack thereof. It’s the Silicon Valley that treats Ridley Scott’s Apple commercial as a landmark moment in Apple history — the Silicon Valley that thinks “think different” means anything. It’s Ashton Kutcher’s Silicon Valley, and the Silicon Valley that consecrated an era that gave GovWorks sixty million dollars.

Pondering Sarah, another Start-Ups cast member sums it up: “She does actually have a reality distortion field.” In Aaron Sorkin’s Silicon Valley, that’s a compliment. Maybe in the real one, too