After 5 suicides in famed pro wrestling family, Tampa woman finds peace

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

TAMPA — “Peace of mind” is tattooed on Nicole Gossett’s left rib cage and punctuated with a semicolon, which is a symbol of hope for those impacted by mental illness.

She’s the third member of her family to adopt that mantra, but the first to find it.

The others were her grandfather and father, Eddie and Mike Gossett, known in professional wrestling as Eddie and Mike Graham. They starred in and ran Florida’s promotion from the 1960s through the 1980s.

Both died by suicide.

“They were big and bold and did big things,” Nicole said. “But they were depressed.”

Mental illness runs in the Gossett bloodline, Nicole said. Five men spanning four generations, including Nicole’s brother Steven, have killed themselves.

It’s heartbreak mirrored by another famed wrestling family of that era. In Texas, the Adkissons, known as the Von Erich family, had five of six brothers die young, three by suicide. Their story will be told in the movie “The Iron Claw” starring Zac Efron, which is out on Dec. 22.

“People often connect us,” Nicole said. “It’s sad that another family has gone through such a tragedy.”

Nicole hopes “The Iron Claw” brings more attention to mental health awareness.

Awareness is why, after decades of silence, Nicole now opens up about her losses. She is featured on the Vice TV documentary “Breaking the Cycle: The Graham Dynasty,” which premiered in June and is still streaming. And she advocates for the Crisis Center of Tampa Bay, whose services include support for those with suicidal thoughts.

“Getting help is especially important during the holiday season,” Nicole said. “It’s a family time, and they’re not here.”

She focuses on the good holiday memories, like her father rolling from his chair onto the floor for a nap after the meal, or her brother giving the women a wet willy as they prepared food. “He was such a dork,” Nicole said.

Nicole also hopes her story inspires others to seek happiness after losing a loved one to suicide.

“It took a long time, but I finally realized that the best way to honor my family is to live my best life,” she said. “I want others to realize that ... and to know that we all process the loss of someone by suicide on our own terms. It comes with time, but it will come.”

Retired professional wrestler and former Hillsborough County commissioner Brian Blair, who is longtime friends with the Gossetts and Adkissons, sees the obvious similarities in the families’ tragedies, but acknowledges a deeper and positive one between Nicole and Kevin Adkisson, the surviving brother.

“I recently spent time with Kevin,” said Blair, 66. “Him and Nicole are a lot alike. They’re both very strong people. They’re both believers despite everything that they have gone through.”

Fame and fortune

From the late 1940s through the early 1980s, different areas of the country had their own regional wrestling promotions, each of which fell under the nationwide umbrella of the National Wrestling Association.

Championship Wrestling From Florida was founded in Tampa in 1949 by “Cowboy” Clarence Luttrall, but Eddie Gossett’s arrival a decade later established it as one of the top promotions in the country.

Inside the ring, his Eddie Graham character was a barrel-chested, blond-haired, blue-eyed All-American who took on other nation’s grapplers when they insulted the United States during the Cold War era. Matches with longtime Russian rival Boris Malenko (he actually was born in New Jersey) regularly sold out arenas throughout the state and garnered front page headlines in a time when the performances were believed to be legitimate competition.

Outside the ring, Eddie was equally virtuous. He raised hundreds of thousands of dollars to help found and then operate the Florida Sheriff’s Boys Ranch in Live Oak, still a residential care facility for troubled children.

Eddie, who is in the WWE Hall of Fame, became sole owner of the promotion that, due in large part to his behind-the-scenes ability to craft storylines for feuds, made stars out of grapplers like Blair, Dusty Rhodes and Jack and Jerry Brisco. Eddie would go on to become president of the National Wrestling Alliance.

Mike Gossett joined the promotion in 1972 after establishing himself as one of the top amateur high school wrestlers in the state. In 1975, the father and son won the promotion’s tag team title.

At that time, before professional football, baseball and hockey arrived in Tampa Bay, wrestling was the most popular form of live entertainment in the area and the Grahams were top celebrities.

“They were the hometown guys,” said Barry Rose, a Tarpon Springs resident who archives wrestling history and promotes conventions. “Eddie was seen as one of the toughest men in wrestling and Mike a literal chop off the block.”

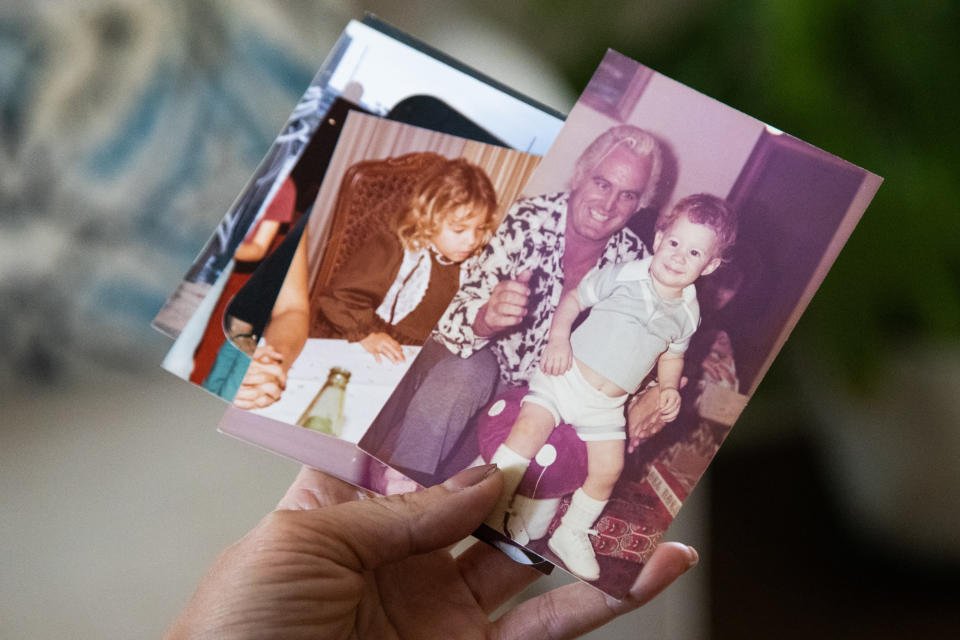

By the time Nicole, now 47, was old enough to forge memories, Eddie was retired from the ring. He still ran the company but had time to be an attentive grandfather to Nicole and her older brother, Steven.

“We lived one street from each other,” Nicole said. “So, he was always at our house. He would take us fishing and flying in his plane. He taught us to scuba dive in our pool.”

Professional wrestlers often hung by that pool, which was shaped like a four to symbolize Mike’s “figure-four leg lock” submission hold. When Andre the Giant visited for the first time, Nicole ran and hid under her bed.

“He looked terrifying but was sweet,” she said.

But Nicole and her brother were largely shielded from wrestling.

“I knew what my father did, but I had no idea how famous he and my grandfather were,” she said. “My father was always bandaged up, so I knew it hurt, but I never went to one match.”

Well, maybe one. Before an event, Nicole, 6 at the time, filmed a commercial with her dad promoting a search for missing children. She was supposed to be escorted upstairs away from the matches, but no one took her. So, Nicole remained in the arena and saw her father beat on another wrestler. When Mike noticed, he sprinted from the ring, grabbed his daughter and raced her away.

Tragedies

Eddie died by suicide in 1985. He was 55, struggled with alcohol abuse and was having financial issues due to bad investments and because much of his top talent was leaving for other promotions that were going national.

“So many people were just shocked and heartbroken,” said Rose, 60, who was living in South Florida at the time. “When your heroes start dying, it has an impact on you.”

The Florida promotion shuttered two years later.

Mike performed for other wrestling companies through 1992 and then transitioned into backstage roles.

Steven killed himself in 2010 at 37. He suffered from substance abuse addiction, Nicole said, and felt directionless.

Nicole found him dead at his house.

“My dad said it was a good thing it was me,” she said. “Because if he had found Steven, he would have killed himself right then and there.”

Mike also struggled with no longer being a celebrity, signified by a tattoo of his mother pulling open his leg to expose an empty wrestling ring with a spotlight on it.

“Without wrestling, he had emptiness,” Nicole said.

Mike, who also struggled with alcohol abuse, took his life in 2012. He was 61.

Around a year later, Nicole’s great-uncle Skip Gossett also died by suicide. They weren’t close, but Nicole said the family stated that he had been sick. She later learned that her great-grandfather, Jess Gossett, took his life before she was born.

Nicole, trying to explain the possible reasons for all of the tragedy in her family, shook her head and said, “Should there ever be a why?”

Peace of mind

After Eddie died, the family found the receipt for the last check he wrote. It was to a liquor store, and he’d scribbled for the note, “Peace of mind.” No one knows why.

Mike got his first tattoo at 40. On the side of his leg, it was a skull with flames coming out of the head and a lightning bolt going through it to symbolize how he “rode the lightning bolts of life,” Nicole said, due to his love of wrestling, boat racing and motorcycles. Below that was the phrase “Peace of mind.”

“He searched for it, but never found it,” Nicole said.

Mike would sometimes blame himself for the deaths of his father and son, lamenting that he must have been a terrible son and father for both men to kill themselves.

Nicole can relate to that.

It was only in the past two years, after more than a decade of grieving, counseling and self-reflection, Nicole said, that she realized “my family’s decisions to end their lives had nothing to do with me. It’s mental illness. I couldn’t focus on that all of the time. I had to live for my daughter. She needs a strong mom.”

But Nicole still worries that the family’s history of mental illness might not bypass her daughter or future generations.

“I am open enough about getting help that she knows she can ask and that there are resources,” Nicole said. “She doesn’t have to be ashamed and, luckily, mental health is something that people are comfortable to talk about today. ... If you need help, please get it. You can have so much in your life. But if you don’t have peace of mind, you don’t have anything.”

Need help?

If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, reach out to the 24–hour National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255; contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741; or chat with someone online at suicidepreventionlifeline.org. The Crisis Center of Tampa Bay can be reached by dialing 211 or by visiting crisiscenter.com.