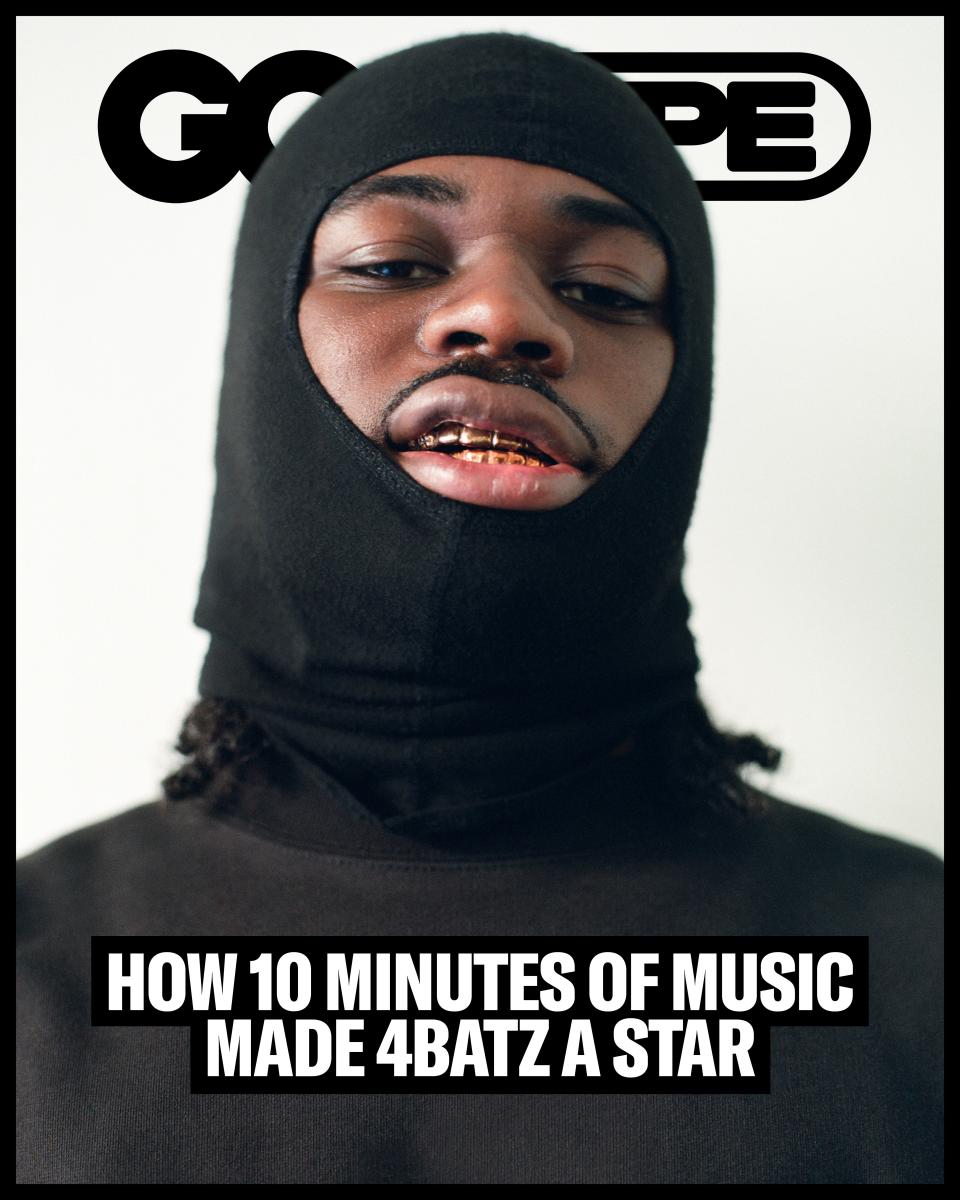

How 4batz Became Music’s Hottest New Star: ‘Ain’t Nothing Calculated’

Clothing, his own. Balaclava and grills, (throughout) his own

This story was featured in The Must Read, a newsletter in which our editors recommend one can’t-miss story every weekday. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Let’s start with his voice—his actual voice, which at press time the public still hasn’t heard. Turns out it’s a baritone, much deeper than his pitched-up vocals would suggest—but not so deep that you would be surprised to learn that he turned 20 last November.

“What does 4batz sound like?” has been a trending search on TikTok and YouTube for months. There are also dozens of videos, think pieces and tweet threads pondering where he came from—a whole cottage industry of social media intrigue, all built around a mysterious kid with just three original songs to his name. (Throw in the Drake remix that dropped in March, and his body of officially released work tops out at just over 10 minutes.)

So who is 4batz, the mysterious, golden-grilled artist who dons a shiesty (more commonly known as a balaclava) the way Batman does a cowl, who’s seemingly materialized out of thin air with TikTok-ready songs hot enough to attract an industry-coveted Drake feature and a shout-out from Kanye? The short version: He’s a Dallas native named Neko Bennett who says he has never had a stable home, once pulled 12-hour shifts at a warehouse to avoid trouble, and became determined to “blow the fuck up” in music in order to make an ex regret dumping him. The even-shorter version: He just might be rap’s next superstar.

The masses got their first glimpse of 4batz in the video for his second single, “Date @ 8,” released last December as an installment on the YouTube channel 4 Shooters Only’s From the Block, a video series that typically features hard-hitting freestyles. In the clip, Batz steps to the mic with a fistful of dollars, braids spilling out of the bottom of his mask, a crowd of his boys around him, blowing smoke and mean-mugging for the camera—and proceeds to sing in a dulcet digitized voice about all the ways he’ll wine and dine a girl who deserves the world, in lyrics that are vague enough to apply to any relationship but also endearingly sweet, unnecessarily profane, and oddly specific (he’s spending “$500 for your fuckin’ hair, $200 for your fuckin’ nails”).

The song was already earworm-y and social-media-ready, and—at two minutes and 20 seconds—short enough to require constant replays. But the video introduced an arresting contrast and sparked many questions. Batz offered no answers, letting the video speak for him. Later that month, Timbaland reposted it and implored Drake to do a remix. In March, that actually happened; Batz further stoked his mystique by remaining quiet even after the Drake version dropped, boosting his already-skyrocketing streaming numbers even further. At press time, his monthly-listener count on Spotify sat just shy of 14 million.

The overused pejorative term industry plant describes an apocryphal type of artist whose career is lab-grown, focus-grouped, and reverse-engineered, someone anointed by nebulous Powers That Be who’ve enlisted top execs, entertainers, and tastemakers to promote them, as opposed to up-and-coming artists with real talent who get “discovered,” signed, and nurtured. 4batz, who came out of nowhere with a handful of compelling songs that quickly accrued millions of streams, was a prime target for plant allegations. Influential podcaster Joe Budden lent credence to a bleak, decidedly 2020s rumor: that 4batz’s music was wholly-AI created, the kid in the ski mask a stand-in for a literally nonexistent artist.

“I think it’s kind of cool,” 4batz tells me, regarding all the intrigue. He flashes a mischievous grin. “It’s like I’m the boogeyman. [Then] people are going to meet me and be like, Oh, this is a regular hood n-gga.”

“Regular” doesn’t quite capture it. 4batz, who grew up and still lives in Dallas, has an excitable drawl, digresses randomly in conversation, and peppers his speech with slang—every sentence ends with a colloquial “brozay,” and every other adjective is “za.” He is, in other words, too endearingly weird to be a paid actor. And his story is too specific to have been cooked up by record-label suits.

Here in a studio in North Hollywood, Batz is wearing the all-black regalia we’ve come to expect from him: black tank top, black track pants, black Balenciaga sneakers, and, of course—even though we’re indoors and it’s 74 degrees outside—the black shiesty. Does he ever move around without it? Sometimes, he says with a laugh, when he wants to travel incognito—but lately he’s been getting noticed even without the mask.

In person, 4batz doesn’t play the brooding man of mystery. He has the motormouth of a hyper teenager, and he’s eager to talk about as much of his life as anyone wants to hear. This Friday, May 3, he’s pulling back the curtain even further with his first official release, a nine-track project called U Made Me a St4r*. And with it, 4batz will officially make his bid as an artist who’s here to stay.

“My whole life, I’ve been feeling like I was cursed,” Batz says. In conversation, he’s prone to casually acknowledging traumatic events that most people would work their way up to. Like how his estranged father died just as they were beginning to reconnect—on Batz’s birthday. How he’s contemplated suicide, more than once. And how he’s never had a real home: “I don't know what it's like to have a house,” he says. “I only lived in an apartment probably two times in my life. The rest of the time I was living with my uncle, my grandma, sleeping on the floor. I slept in a church for four years.” At one point, he stresses that he doesn’t come from “the hood,” but rather, “the slums.” He later adds that LA is “too cute” for him to ever lay his hat there full-time.

His stage name is a homage to his upbringing: the 4 refers to the part of Dallas he’s from, and Batz, he says, comes from his reputation for fighting and holding it down: “You know—when you bat [someone] the fuck outta here.”

Most, if not all, great music success stories have that singular origin moment. In the music he’s released so far, Batz has dropped breadcrumbs about his own story for listeners to connect with, but now he’s ready to make it plain.

“I went through a situation in my life” is how he tentatively begins his tale. It starts, as it often does, with a girl. Batz, who had never even flown in a plane before, found himself in a long-distance situation with a girl from Chicago. She came down often to visit. “Bro, shorty was such a vibe,” Batz recalls, tugging at his mask. “I was in love with her, man.”

The relationship lasted three years, and Batz entertained the idea of their moving in together; to show his dedication, he planned to take his first flight ever to go see her.

“Then she called my phone,” he says, “and she said, ‘Batz, I don't want to be with you no more. I'm just not fucking with you.’ Around that same time, literally a month before that, my pops died. So I said, ‘All right, well, if you do that, I'm going to blow the fuck up. I'm going to be on all these interviews, I'm going to be on all these blogs, I'm going to be on all these motherfucking…. I'm going to be everywhere, and I'm going to shit on you. I'm going to make you feel bad.’ My blood was boiling, bro, and I was just going in for like 10 minutes straight with my eyes closed, and by the time I stopped talking I noticed she had hung up. And then I was like, Shit, she doesn't care no more.”

The next morning, Batz woke up to see her already flaunting a new guy on Instagram. He recognized him as one of his ex’s coworkers—literally the man she’d told him not to worry about. (During the relationship, some suspicious Snapchats had inspired him to FaceTime the guy from her phone, to ask if they had a problem; the guy said they didn’t.) “He played his role like he was Michael B. Jordan. That boy need an Oscar,” Batz wisecracks ruefully.

“At this point, I'm in deep depression, I'm fucked up,” Batz recounts with a whisper. “I'm still grieving for my pops, and at that point in my life the only person that I had, period, point-blank, was her. I wasn't close to anyone else. I love my mama to death—I wasn't close to my mama. I wasn't close to my grandma. Ol’ girl”—his girlfriend—“was like my best friend. So, at that point I was thinking just about suicide, thinking about so much shit.”

This wasn’t Batz’s first time hitting rock bottom, or even contemplating ending it all. “My whole life I've been through shit,” he says. “I've been on suicide watch before. I've been on all these other programs, taking antidepressants and shit. I've been on that shit. I was at the point where I'm tired of it. I was like, I could just take myself and be gone or I can push myself harder than I ever did in my life.”

Heartbreak plus spite bred determination. Batz pivoted back to making music, which he’d neglected during his relationship, in part because his girlfriend hadn’t supported his aspirations. In a bid to firmly remove himself from the street life, Batz held down a 12-hour shift in a warehouse while installing himself on a Kanye-esque, three-songs-a-session regiment when he clocked out at night, downloading beats from YouTube and trying different things over them—all while pursuing his last remaining high school credits.

He tinkered with different styles and subgenres. “Drill music, Texas music, emotional music, hurt music, ‘Baby, why you hurting?’ music,” he says. “Doing everything in my power, just trying to get on. And that was the issue—the fact that I was trying to get on.”

These experiments, he says, weren’t solid enough to share, let alone upload to Soundcloud. Then one day, inspiration struck as he was doing what he calls his “pre-workout ritual”: looking at a picture of his ex and her new guy. “I felt like a bitch. This girl talked crazy about me to her friends, she made me feel little, she cheated on me—but I’d still get up and go fly to her."

The first bar came to him: I might just call and catch a plane. I might just come see you today. You hate I'm stuck up with my ways, but loving when I'm playing games. And then in one take, another minute’s worth of scorned-lover lyrics and unrequited yearning came pouring out. It was what we now know as his first song, “Stickerz ‘99.” The title is a metaphor for the mindset he found himself in. “When you get a sticker and you put it against the wall and you take it off, you put it back on the wall and you take it off—you do that 40 times, by the 40th time it's not going to stick on the wall,” he says. “So, basically I'm stuck to someone that don't want to be stuck to me.”

That raw vulnerability gets downplayed with the vocal pitch-shifting Batz deploys, first turned up super high so as to sound almost alien, then a chopped-and-screwed encore of the same lyrics to close the song out. Batz cites the decision to alter his vocals as typical Texas shit—DNA from DJ Screw, the late Houston legend who pioneered the art of chopping tempos and vocals down to a glacial pace for a slower, more Southern speed—but hints that some songs on U Made Me a St4r* actually feature his real, un-altered singing voice, though he won’t specify which ones.

Batz tried different, longer takes of the song, all of which he says “sounded horrible.” It was that brief first-take version that got the most positive reactions out of the close confidantes he tested his music with, like his older brother.

He took it as a sign to double down on what felt true, regardless of precedent, and to present himself in his music as who he actually was: a young man raised on Mint Condition, 112, Sade, and Anita Baker via the likes of his mother and grandmother, with an appreciation for DMX and 2Pac courtesy of his father before he passed, and an affinity for the likes of Chief Keef from his own generation. As Batz puts it: “I remember those times I was in a stolo”—a stolen car— “in Dallas, pushing that ho on the highway, and Aaliyah comes on while I'm sipping lean, or while I'm, like, clutching my gun. And I realized, Why is this [considered] yin and yang? Why has nobody put these [feelings] together? And I said, You know what? I'm that. Why can't I?"

When he finally took his maiden flight, it was to LA, to make a video for “Stickerz” with some creators who’d hit him up, offering a shoot. It’s a cool clip, but as he sits, maskless, getting his hair braided by a pretty girl or rapping mournfully on the edge of the bed, there’s nothing much there to distinguish him from the vast sea of up-and-comers uploading videos to YouTube.

Coincidentally or not, no one cared about 4batz until he put on the shiesty. This is not without precedent; the terminally online will remember RMR, the ski-masked Minneapolis rapper who went viral in winter 2020 with the video for “Rascal,” wherein he croons Rascal Flatts’ power ballad “These Days” while he and his goons flash grills and point firearms at the camera. But what RMR was doing with that juxtaposition of song and image felt more deliberate and performative. “At the end of the day,” RMR told one interviewer, “I’m doing this because people are so ignorant within their own box and they don’t want to venture outside of their reality, per se.”

4batz insists that his own blend of sound and visual presentation— a street dude singing softly about heartbreak while seemingly dressed for some light B&E— isn’t meant as a statement.

“We've been wearing ski masks since we was kids. It's not no costume, bro. It's just how I ride,” Batz says. “Ain’t nothing calculated. I did it because this is my type of shit. I'm bringing people to my world and if they like it, they like it. If they don't, I don't give a fuck. It's like a door: If you want to get in, hey, come on, we're partying in here. But if you don't, hey, stay your little dumb ass outside, then. We're chilling.”

“I think the similarity is in the imagery,” says Carl Chery, Spotify’s Creative Director and Head of Urban Music. “You have someone with a ski mask who very much presents as if they're a rapper, but they're not. But unfortunately, RMR wasn't able to follow up that moment with music that resonated. The difference with 4batz is that there's already a few songs that are working. It's not just ‘Date @ 8’ and the remix, it's ‘Stickerz’ and ‘On God’ as well.”

Chery notes that Batz’s current numbers—those 14 million Spotify listeners—are empirical proof of real, sturdy engagement. “We as a community of rap and R&B fans tend to make lazy observations,” he says. “We see the one little thread and make a comparison. That always happens for new artists. I think if 4batz is fortunate enough to be successful with this mixtape, and keeps growing his fanbase, the RMR comparisons are going to be far in the rear view mirror.”

“Listen, if you look at everyone who's had success at a very accelerated rate, whether it's Ice Spice or Travis Scott, fans are going to call everybody like that an industry plant at some point, until they don’t anymore,” says Milano, 4batz’s manager. “I look at it as a compliment. It just lets me know that he's so talented. For people to think at some point that he was AI—it's crazy, but it also speaks to how they can't even imagine that someone could really be that talented.”

The “Stickerz” video may not have broken Batz out, but it’s how he met Milano and other like-minded music-industry people who came to form the team that’s around him now. “He played his music for me [the day of the shoot], and he didn't have a team. It was just him grinding,” Milano recalls. “We just started building from there. I was giving him ideas, he's rolling ideas off me, and we were just bouncing off each other.”

Those ideas all centered on Batz’s instincts to not flood the zone with a lot of music and take any opportunity to stand out. Batz points out that he dropped “Date @ 8” and its visual in the heart of December—typically a music-industry no-no. But the no-man's-land of the holiday season left a lane wide open for him.

Batz also rejects genre labels. His new songs evoke the pubescent heartbreak of say, Immature or Tevin Campbell, with production that sounds inspired by the likes of Age Ain’t Nothin But a Number, 100% Ginuwine, Case, or early Usher, but when I ask if some of his original stabs at finding his sound were more rap oriented, he looks confused. “I'm still a rapper,” he replies, before doubling down, almost as if he’s talking himself into the idea. “I feel like I'm rapping. Yeah, I'm rhyming and shit.”

If his songs sound more like R&B, that’s just emblematic of Batz’s mission to tear down music’s rules and strictures. As Batz plays me the new mixtape, he leaps around the empty studio, his dance moves a hybrid of new jack swing yearners like Mario Winans and Keith Sweat and Travis Scott-style turnup. I’m reminded of Scott’s second album, which was peppered with love songs that at first listen seemed like they’d be incongruent alongside his bangers in concert—only for him to turn a song like “Sweet Sweet” into something crowds still had to levitate for.

“We're in this interesting stage where the lines couldn't be blurrier between hip hop and R&B,” Chery says. “[Batz] is 20—what's interesting about his generation is that they don't care about making the distinction between the two.” Chery notes Spotify’s R&B playlist RNB X was the first to embrace Batz, even placing him on the cover art for a time—where his decidedly un-R&B visage immediately drove consumption. Once the Drake remix of “Date @ 8” hit, Chery took a gamble by adding it to Rap Caviar, where his observations about Gen-Z’s disregard for genres paid off: “They don't really care about the distinction…they would appreciate a song like that right after Lil Tecca’s ‘500lbs.’”

Batz starts the tape for me from the top, with the three singles playing in succession, encouraging me to rap along with him like we’re two homies watching Funk Flex freestyles instead of dueting sing-songy lyrics about paying for nail appointments. When we finally get to the new stuff, his excitement increases: “Now, we about to get into some shit,” he warns.

Like the singles, each new track has a header (e.g., “Act 1”). There are skits explaining a truncated version of the heartbreak story he’s just told me, but they’re unnecessary; the story is already there in the music. Batz is building a mythology in real time, one he compares to “one of those old testaments or testimonies.” He mimes blowing dust off some ancient tome, like he’s in Raiders of the Lost Ark, and says, “I’m making history.” And just in case the tape’s title doesn’t make his muse clear, the cover art shows him holding a crossed-out picture of his ex.

The music on the back half of the tape answers the skeptics who found Batz’s first songs compelling but slight. The five new songs aren’t much longer, but they still feel like more complete thoughts, while also sharpening his storytelling. Lines like “There goes another vase”—as in another home ornament thrown and shattered in a toxic fight, underscoring a volatile rapport that just strengthens Batz’s belief that the relationship he’s singing about is built to last—feel significantly less edited for TikTok.

“I wonder how inspired he's been by this trend of altered vocals, because artists are now putting out music where they actually feed into the whole Tiktok craze and release sped-up versions of their songs,” Chery says, “And I think it's kind of brilliant for him to be like, ‘OK, no, the original product is gonna be me having a voice that's altered.’”

4batz’s aesthetic is the logical next step on the path forged by artists like Drake, who’s shuttled between soft pop songs and frat-bro raps, as well as the harder-edged approach of an artist like Future, who just released an album of vulnerability alongside an album of elite street-boss talk for the second time in his career. 4batz is the sensitive thug who can credibly cite both Sade and Chief Keef as inspirations, who croons about his Ruger as tenderly as he does the girl who almost ruined his life. Is it really hard to conceive of Drake connecting with this music enough to give it his stamp without being paid to do so?

When I ask about the Drake remix, Batz simply says he’s grateful a star like that is showing him love. But he isn’t one to get starstruck. Outside of Ye reaching out through his team and FaceTiming him randomly last fall—a call that Batz says “made my year”—he says that the only celebrities he’d be excited to meet would be DMX and 2Pac, his dad’s favorites. In March, when Drake’s It’s All a Blur–Big as the What? Tour hit San Antonio, Batz was invited to attend as a guest of the headliner; it was the first concert he’d ever been to. His key takeaway from the experience? “I got to make more songs.”

Drake’s OVO imprint is distributing U Made Me a St4r*, but 4batz remains unsigned. On the rumors that Batz may make his affiliation formal, Milano says, “We're always building. Those guys—40, Morgan, Drake, Future the Prince—they've extended their hand in building the relationship. It's like that with everyone in the industry who Batz has come in contact with. They really like him and they understand who he is. We're going to build relationships throughout the industry with who makes sense to build with.”

“He really is a reflection of the time,” Chery says. “He started making music like a year ago, he uses mystery and cultivates a mystique. He alters his voice. He blurs the line between two genres. I don't want to make a declaration, but he's a snapshot of today's artist.”

Batz already has grand plans for the project he’ll officially deem his debut album. So far, he’s following a path not unlike the one traced by The Weeknd—the shadowy figure with an angelic voice who slowly but surely emerged into the bright lights. Batz notes that, as Weeknd most effectively symbolizes, every artist “has their eras.”

To hear him tell it, we’re still only in the first act of the 4batz story. If a couple of viral songs have the industry mad and confused enough to label him a plant, then he’s excited to see how his peers react to this new project and whatever follows. “Wait until they hear this fucking tape,” he says animatedly. “They're going to be like, ‘I hate this n-gga.’”

When he spoke to Kanye, Batz says, “He was telling me, ‘Get used to it, because you here now. People are going to look at you like a walking ATM, but you're going to see through that. You know what I'm saying? Because you a star.’”

The day fades to dusk. Batz’s team has courtside seats to watch the Warriors play the Lakers, but he waves the opportunity off. He’s got gym two-a-days to complete, shows to rehearse, new songs to fine-tune. Real stars aren’t grown in a lab.

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

Photographed by Zhamak Fullad

Styled by Jason Rembert

Skin by Hee Soo Kwon using Dior Beauty

Originally Appeared on GQ