25 Years Later, Space Jam Still Slams with Looney Antics and Legitimate Heart

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The post 25 Years Later, Space Jam Still Slams with Looney Antics and Legitimate Heart appeared first on Consequence.

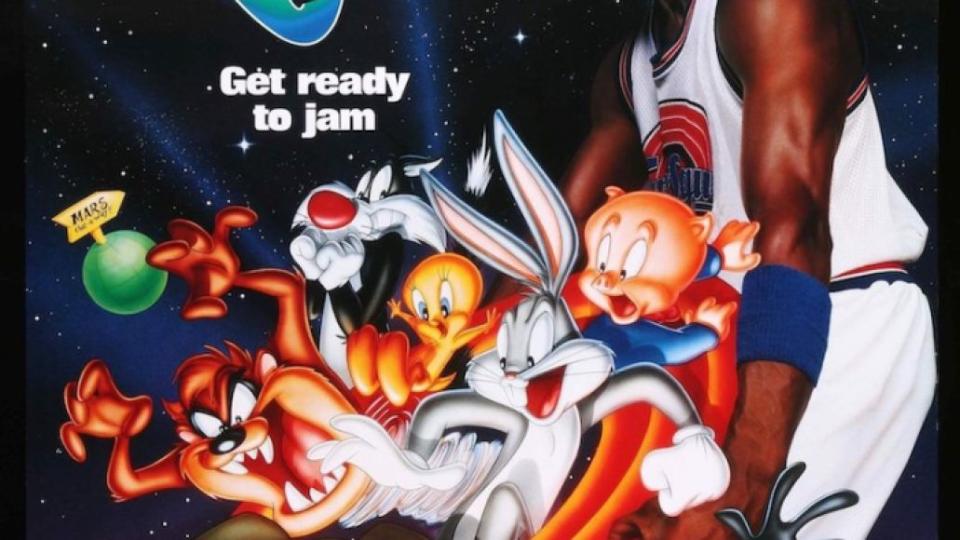

Virtually every ‘90s kid grew up with Space Jam, now celebrating its 25th anniversary (cue Feel Old? jokes). Released on November 15th, 1996, the groundbreaking movie built upon past cinematic fusions of live action and animation — from Fantasia and Mary Poppins to Pete’s Dragon and Who Framed Roger Rabbit — to charm countless children who adored basketball, cartoons, and/or trendy music.

Of course, its wide-ranging marketing and merchandising campaigns guaranteed its global domination, leading to a pervasive place in pop culture that’s stayed consistent ever since.

Inarguably, the film left an indelible mark on an entire generation of adolescent moviegoers, including myself. (I first saw it during my 5th grade Thanksgiving party, and I quickly grew to share my classmates’ collective obsession.) Twenty-five years later — and despite some overt flaws — Space Jam endures as a superb new experience for young viewers, a superb bit of nostalgia for young adults, and a superb testament to the power of imagination, technological innovation, and zeitgeist capitalization.

At the time, combining Looney Tunes and Michael Jordan might’ve seemed risky and absurd (indeed, supervising animator Bruce Woodside strongly doubted that Space Jam would truly give Bugs Bunny and friends “a successful second life in features”). Today, however, it’s easy to see how various stars aligned to make it a logical and assured project.

For one thing, the Looney Tunes were in desperate need of revitalization, as they’d basically been relegated to various syndicated TV appearances, home release compilations, and theme park tie-ins during the first half of the decade. Meanwhile, Michael Jordan had just returned to the Chicago Bulls after spending some time playing baseball — with the Chicago White Sox, Birmingham Barons, and Scottsdale Scorpions — throughout 1994.

That said, the real impetus came a couple of years earlier, when director Joe Pytka shot two very popular Nike Super Bowl commercials (“Hare Jordan” and “Aerospace Jordan”) that, as he put it, provided the then-reluctant Warner Bros. with “a nice bit of research… to understand that the Bugs character still had relevance.”

Although everyone involved knew that it would be an arduous process full of uncharted technical territory, the triumphs of those advertisements — coupled some gigantic retail capabilities and a story idea that could fruitfully combine Looney Tunes zaniness with Jordan’s real-life athletic arc — convinced the production company to bring the pair to the big screen.

Naturally, Pytka was hired (by producer Ivan Reitman, who was advised against doing the movie by Who Framed Roger Rabbit mastermind Robert Zemeckis) to make Space Jam a reality. Over the next 19 months (and with the help of “18 studios around the world,” including ones in London, California, and Canada), he and hundreds of other crew members transformed Space Jam from a mind-bogglingly ambitious prospect into a cutting-edge entertainment phenomenon.

While the plot of the movie came together fairly easily (even after Spike Lee, who also starred opposite Jordan in a Nike promo, was prohibited from participating), the casting proved to be more problematic. For instance, the part of Jordan’s publicist/handler, Stan, was initially pitched to Jason Alexander, Michael J. Fox, and Chevy Chase before it went to Alexander’s Seinfeld co-star, Wayne Knight. Similarly, Danny DeVito’s villainous Mr. Swackhammer — who manages the antagonistic Monstars — was supposed to be a live-action character portrayed by Dennis Hopper.

Luckily, Knight and DeVito give stellar performances, and the rest of Space Jam’s cast is obviously ripe with notable talent (such as Bill Murray, Larry Bird, Patrick Ewing, Charles Barkley, Muggsy Bogues, Theresa Randle, Billy West, June Foray, Frank Welker, Bob Bergen, and Bill Farmer). Famously, Mel Blanc successor Joe Alaskey auditioned, too, but eventually “backed out” after concluding that Reitman couldn’t “make up his mind” about whether or not he should join the team.

As for Jordan himself, well, he was on board from the beginning, and he continuously used his time in-between filming to mingle with people and get ready for the upcoming 1995-96 NBA season. “Every day in between shots, he would go practice. And every night, he’d usually bring in some pros in the area, or college kids, and they’d play basketball,” Warner Bros. executive Bob Daly has said. The studio actually built an indoor gym (“Jordan Dome,” as Pytka calls it) just so he could practice as often as possible, and by all accounts, Jordan exuded friendliness and professionalism throughout the shoot.

It would take a whole essay just to discuss all of Space Jam’s forward-thinking technical accomplishments, but suffice it to say that the crew’s fearlessly exhaustive work ethic permeates nearly every frame of the film. According to visual effects supervisor Ed Jones, it was among the first films to be shot on a virtual set, with Jordan playing against motion-tracked actors in a 360-degree greenscreen.

From there, and with support from renowned VFX company Cinesite, they experimented with various effects and techniques — such as chroma-keying, motion blur, miniatures, and 2D to 3D digital conversion — to bring it all to life, creating new industry standards in the process.

Animation director Bruce W. Smith surmised: “We were producing this movie during the age where digital was still meeting analog, but also taking its place. It was difficult because a lot of the stuff we were doing hadn’t been done before… It was a great time in animation.”

Admittedly, Space Jam never received much critical praise — although Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel gave it positive reviews — but that didn’t stop it from being a box office triumph. Specifically, it earned over a quarter of a billion dollars worldwide, becoming both the highest-grossing basketball film of all time and the tenth-highest-grossing film of 1996. Its numerous home releases, starting with the original VHS run back in March 1997, were also quite profitable.

Outside of that, Space Jam engendered one of the most expansive merchandising campaigns in Hollywood history. For example, the soundtrack — featuring R. Kelly, Seal, Busta Rhymes, Coolio, LL Cool J, Method Man, Monica, Techotronic, and Salt-N-Pepa, among others — was eventually certified 6x platinum. (Like the movie itself, it now serves as a beloved musical flashback to a bygone era.)

There was also an abundance of miscellaneous video games, Happy Meal tie-ins, apparel choices, action figures, plushies, posters, and even a DC Comics graphic novel. Of course, the official website — whose longevity and dedicated following is a story unto itself — must be mentioned, too.

For a time, Space Jam was everywhere, and rightfully so.

Unsurprisingly, it’s continued to infiltrate and influence popular culture ever since. Not only did it receive two successors in 2021 (crossover Teen Titans Go! See Space Jam and direct sequel Space Jam: A New Legacy) but it also spawned a pseudo-offshoot with 2003’s Looney Tunes: Back in Action. There were also a ton of new TV shows and direct-to-video movies, such as The Sylvester & Tweety Mysteries, Duck Dodgers, The Looney Tunes Show, and Looney Tunes: Rabbits Run.

More tangentially, it was referenced in a 1998 Pinky and the Brain episode (“Star Warners”), in late ‘90s MCI commercials, and elsewhere. While Space Jam: A New Legacy was less successful than its predecessor (in pretty much every way), it nonetheless sparked enough new interest in the franchise to generate considerable hope for a potential third film.

Removed from all of its immensely lucrative and sundry — if also divisive — aftershocks, Space Jam itself remains extremely likeable and laudable. Namely, the plot holds up as a simple but effective way to get Michael Jordan and his cartoon costars to unite toward a common enemy. Mr. Swackhammer and his Monstars represent a threat to all involved, so both sets of heroes have an interest in defeating them to save the Looney Tunes and restore talent to Jordan’s real-life colleagues.

The movie also does a good job of building up to their inevitable partnerships and confrontations by showcasing what all three parties (Jordan, the Looney Tunes, and the Monstars) are up to during the first act. Thus, there’s a decent amount of payoff and audience investment once the story really gets going, and the frequent intersection of fictionalized zaniness and Jordan’s actual upbringing/career result in several genuinely heartfelt moments.

On that note, all of the drawn characters are enjoyable because they’re supported by compelling performances. That’s not to say that anyone is Oscar-worthy, but every Looney Tune feels authentic yet also slightly edgier and fresher than they’d been in other mediums during that time.

As Smith explained: “We knew who the characters were going to be in the movie, but as characters they had evolved over time in the Looney Tunes world.” That growth is evident not only in their increased sense of fantastical wackiness, but also in how they embody the 1990s (such as a gag in which Daffy Duck wears some illustrative hip-hop attire).

Space Jam Vs. Space Jam: A New Legacy: A Side-By-Side Comparison

Fortunately, the live action actors fit in nicely. Naturally, Knight and Murray steal every scene they’re in, generating just enough quippy energy to be endearing without being obnoxious. The NBA stars aren’t as skilled or memorable, sure, but it’s precisely that kind of novice awkwardness that makes them appealing. The same goes for Jordan, as his consistent charisma and playfulness are enough to compensate for his lack of professional acting ability. In other words, he’s clearly having fun the entire time, so viewers are as well.

The humor of Space Jam holds up fairly well, too. Yes, a lot of it is unfashionable and/or aimed at children, but that doesn’t mean that it’s no longer charming (especially when Bugs Bunny engages audiences by letting them in on an upcoming gag).

There’s also plenty of sly adult humor scattered around, be it references to Pulp Fiction and Patton; a send-up of Freudian analysis; a self-referential bit about Jordan’s many product endorsements; or Daffy and Bugs discussing how they’re “getting screwed” by not making money off of all their merchandise. There’s even a handful of sex jokes strewn around (such as Ewing being asked if he’s “unable to perform” in “any other areas besides basketball,” and Bugs literally getting stiff when he first meets Lola Bunny).

Even the film’s most dated aspect, its CGI, is never too egregious (well, except for maybe some shots of the Monstars’ 3D spaceship). Plus, it’s easy to appreciate those flaws in hindsight because of how revolutionary they were. By and large, though, everything still looks really good, with various styles merging in ways that are, by today’s standards, modest yet attractive and clever. The movie knows its technological limitations, so there’s no risk of sensory overload (which can’t be said for the far too busy and complex Space Jam: A New Legacy). Add to that Pytka’s relentlessly fluid and inventive camerawork and you have a sufficiently cinematic and vibrant vibe that’s lost little of its luster.

By traditional standards, Space Jam is not a great movie. But, that doesn’t mean that it’s not a great moment in movie history. Indeed, its sweet narrative, state-of-the-art visuals, fun cameos, lively soundtrack, and central pairing yielded one of the biggest entertainment spectacles of the decade. For those who grew up with it — such as myself — it lingers as a vital part of childhood, and its myriad technological advancements paved the way for modern blockbusters, pop culture crossovers, and the like.

Hollywood may’ve come a long way since the mid-90s, but Space Jam will always be something special.

Space Jam is currently streaming on HBO Max.

25 Years Later, Space Jam Still Slams with Looney Antics and Legitimate Heart

Jordan Blum

Popular Posts