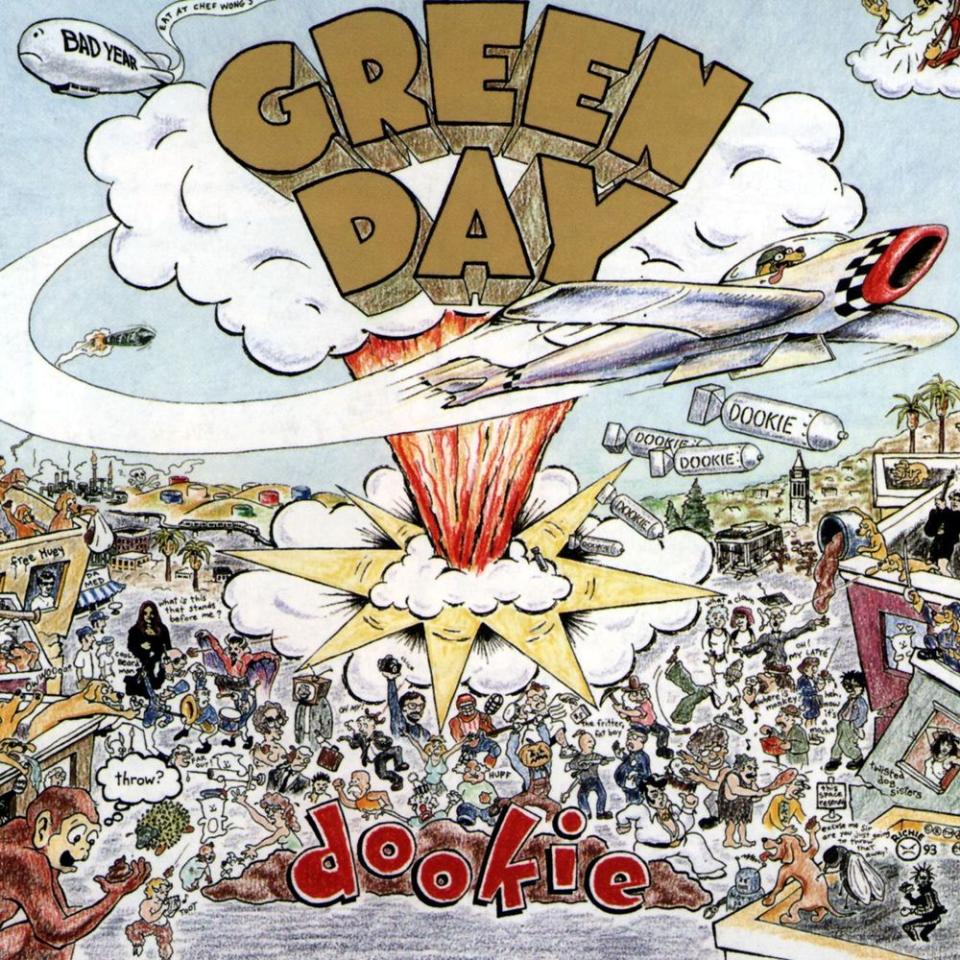

25 Years of Dookie: How Green Day's breakthrough shaped the '90s

Green Day were not a band poised to take over the mainstream. Their name is a reference to an entire day spent stoned, their breakthrough album is named after poop, and its three lead singles casually lob references to masturbation and prostitution alongside the de rigeur 1990s lyrical touchstones of mental illness and generational malaise. They were a group that deliberately avoided taking themselves seriously, and consequently, hindsight bestows Nirvana’s Nevermind with the honor of being the big cultural reshaper of the ’90s, the hair-metal killing monolith that brought underground culture to a global audience. Kurt Cobain’s death in 1994 saddled the band’s story with an inescapable aura of importance, and that’s just the way it’s been ever since.

But looking at things now, there’s a case to be made that while Green Day’s Feb. 1, 1994 breakthrough Dookie may not have toppled hair metal, 25 years on, its legacy is every bit as important as Nevermind — and maybe longer-lasting. (Just look at the cover of Vince Staples’ FM!.)

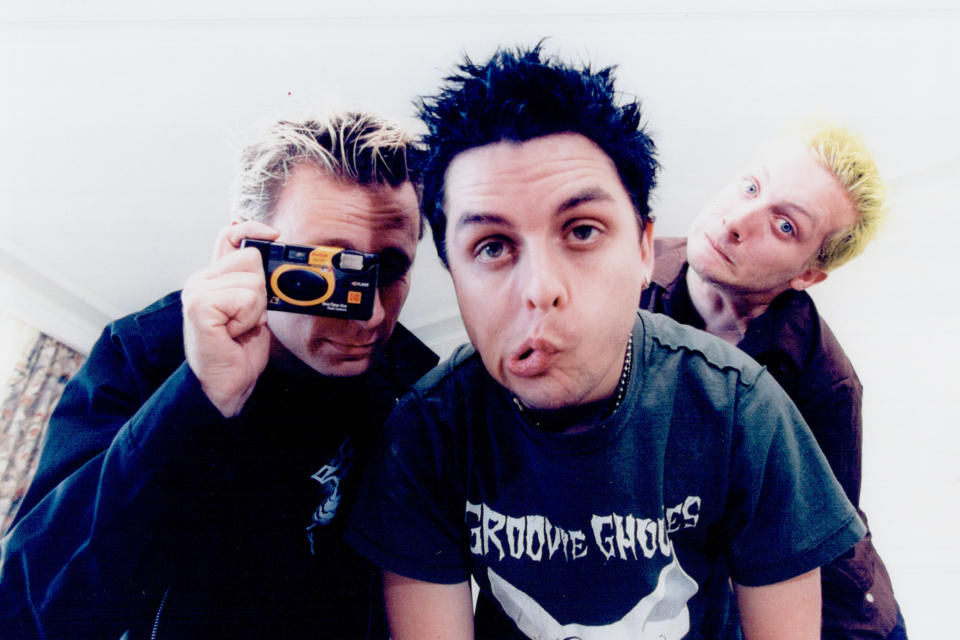

Green Day came up in the trenches of the Bay Area punk scene, slogging it out in a world centered around Berkeley’s legendary Gilman Street venue. Billie Joe Armstrong has a cowrite on Rancid’s “Radio,” off that group’s pre-breakthrough album, Let’s Go!, which illustrates just how nestled into the movement Green Day was. They kicked around a couple of releases on seminal East Bay label Lookout! Records before dropping Kerplunk, which sold a reported 10,000 copies on its first day of release and got the major labels sniffing around. (Also relevant: It’s Serena Williams’ favorite album.)

The grunge explosion resulted in hairy, largely self-serious men blasting out anthems of disenfranchisement. With the exception of Pearl Jam, who always wore their blooz-rock love on their sleeves, when you think of the era’s defining sounds, you’re generally thinking of the messy, heavy tones of Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains.

Green Day could not have been further from this sound: Armstrong’s writing references were the Replacements and Hüsker Dü, both of whom were credited with pushing songwriting and melody to the fore during the 1980s’ punk and hardcore movement. Soundgarden and Alice in Chains were riff merchants who capped that approach with towering vocals: Billie Joe Armstrong sang memorable hooks in a nasal honk (and a seemingly affected British-y accent) and trafficked largely in nimble power chord-driven progressions, not detuned slabs of sludgy guitar. “We get lumped into this bandwagon of this f—-d-up mentality,” he noted to Rolling Stone in 1995. “[But] to me, punk rock was about being silly, bringing a carpet to Gilman Street and rolling your friends up in it and spinning it in circles.”

Now, the conventional wisdom is that grunge’s hunger-dunger-dang bleat and plodding sonics eventually mutated into lazier and more derivative groups (Bush, for example) and, eventually, the nü-metal sound that would dominate the early 2000s. And this is a largely accurate read, except it ignores the concomitant stream of music that was happening at the same time, which is basically what we know today as pop punk.

The guys behind the board for Dookie, Jerry Finn and Rob Cavallo, would midwife the pop punk sound into existence. Cavallo was a music industry vet when Dookie catapulted him into the mainstream; he would stick with Green Day but go on to have a hand in multiple hits from other bands, Goo Goo Dolls’ omnipresent “Iris” among them. (Also, uh, multiple cuts from Phil Collins’ Tarzan soundtrack.) Finn went from being a largely unknown engineer to the defining pop punk sound man: The genre’s punchy guitar tones and in-your-face vocal mix was entirely due to Finn’s technical approach. He’d codify the sound with a number of albums, like Rancid’s …And Out Come the Wolves and Jawbreaker’s Dear You, before going on to forge a lasting relationship with Blink-182, becoming their George Martin figure — Mark Hoppus referred to him as the band’s “fourth member” — from 1999’s Enema of the State onwards. (He also worked with basically the entire bench of pop punk players from the mid-’90s onward, including AFI, Sum 41, Pennywise, and Alkaline Trio.)

Dookie was basically in place by the time the band arrived at the studio: “Welcome to Paradise” had already appeared on Kerplunk, and “Having a Blast” was written in 1992. Pop punk largely takes its cues from the Ramones’ no-frills tightness rather than the Clash or the Sex Pistols’ pub-rock-y swing, and Dookie is ground zero for this sound: Bassist Mike Dirnt and drummer Tre Cool churn nimbly under Armstrong’s buzzsaw guitar. Dirnt in particular took the bright, aggressive bass playing of Rancid’s Matt Freeman and streamlined it: The instantly recognizable walking bass line to “Longview” is a great example, as is his burbling part on “When I Come Around.” Given all these factors, tracking the record didn’t take long, but the band ended up rejecting the first mix of the record and re-doing it. For all the “sell-out” accusations lobbed at Green Day after the fact, in hindsight, Dookie sounds exactly like what it was: A band who’d made their bones in the indie world making a play for the mainstream. Armstrong was not shy about this: “I honestly wanted [Dookie] to be one of the biggest records of all time because I couldn’t see any middle ground,” he recalled to VH1. “There’s something about mediocrity that I don’t want anything to do with.”

Another major player in this narrative is The Offspring’s Smash. Released in April ’94 on what would become the de facto California punk imprint, Epitaph, Smash has sold 11 million-plus copies worldwide (Dookie eventually went on to sell almost double that), and while a song like “Self-Esteem” has a little more of that mid-tempo grunge swing, much of the album’s sonic template is similar to Green Day’s. The other two big OGs of Epitaph, Rancid and NOFX, were also having big 1994s: NOFX released Punk in Drublic, their most popular album, in July, landing them on the Billboard Heatseekers chart almost a month to the day after Rancid cracked the Billboard Top 200 with Let’s Go! Bad Religion would join their California brethren in September, when Stranger Than Fiction hit No. 87 on the Top 200.

So even though 1994’s popular image is shrouded in flannel and the mists of Seattle, a handful of California bands were putting out some of the best-selling alternative records of the year that also functioned as a rebuke to the doom-and-gloom sounds of grunge. Major labels quickly took notice, which leads us to 1995.

Rancid’s …And Out Come the Wolves came out in 1995, as did Jawbreaker’s major-label debut Dear You. The former was a big hit, led by radio stalwarts like “Ruby Soho” and “Time Bomb,” while the latter flopped. But Warped Tour’s first iteration launched in 1995, and Green Day’s Insomniac, a moodier follow-up to Dookie, climbed all the way to No. 2 on the Billboard 200. One of the ripple effects of this new California sound’s dominance was that record labels started taking ska revival bands seriously; “Time Bomb” was a big enough hit that suddenly any band who played guitars on the upbeat seemed like a viable commercial prospect. You may be familiar with a little album called Tragic Kingdom that we got out of this, but second- and third-tier ska bands like Reel Big Fish and Goldfinger also notched hits of varying degrees.

All of which leads us to Blink-182. The band had been kicking around since 1992, and by 1996, they’d built enough buzz to become the subject of a bidding war between RCA, Interscope, and Epitaph. Their major label debut, Dude Ranch, was recorded in late 1996 and released in June 1997; lead single “Damnit” quickly propelled them to stardom and opened the floodgates for a whole new bumper crop of pop-punk bands, like AFI, New Found Glory, Good Charlotte and so forth. So that’s basically three years from Dookie to the next biggest fad in alternative music. Green Day would obviously go on to embrace the trends they begat; they toured with Blink-182 in 2002 and seem to have contentedly settled into their elder-statesman status.

The ripple effects are still being felt: Fall Out Boy and Paramore are two of the bigger mainstream “rock” bands, and both started as far more explicitly pop-punk bands. Fall Out Boy would, when inducting Green Day into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, describe the band as their “reference point for everything.” Paramore’s Hayley Williams tweeted about seeing Green Day as late as 2012, and Australian punks-by-way-of-One Direction 5 Seconds of Summer consistently name-dropped the group when they rocketed into the mainstream in 2014. Melkbelly’s Miranda Winters just told Consequence of Sound that “I was, like, instantly obsessed with [Dookie]” when she first got it around 2000, before adding “I learned a lot from this album.”

For a record that rockets past in 40 minutes, Dookie has had a long shelf life. And for a group of snotty East Bay potheads, Green Day casts a long shadow. It may have taken us a while to come around, but we’re fully in on this basket case.