21 Savage Is Finally Free to See the World. We Came Along for the Ride

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Smack in the center of Paris’ Trocadéro esplanade stands 21 Savage, face-to-face with the Eiffel Tower for the first time. It glows in the distance, across the Seine river, as a light rain falls and dusk settles around us. He’s flanked by four security guards, all dressed in black like Savage, whose eyes peer out of a slick ski mask and North Face hood.

Savage’s team giddily snaps pictures while he looks on, surrounded by a bustle of tourists. A salesman sets down the light-up Eiffel Tower toys he was peddling and volunteers to take group photos of Savage’s entourage, which includes Buwop (née Kenya), Savage’s right-hand woman and friend of nearly a decade, and Meezy, his manager. When Buwop wants a solo shot, the salesman gives her tips on how to pose in front of the tower like she’s pinching it from above. “Oh, he know what he doing!” Meezy says.

More from Rolling Stone

The Gerontocracy Waged War on Gen Z. Now They're Fighting Back

Beyoncé and Taylor Swift Shared Spotlights This Year - Their Legacies Are Still Incomparable

Go-Go's Guitarist Jane Wiedlin Claims Influential Rock DJ Sexually Abused Her as a Teen

At some point, as his friends enjoy the scene, Savage slips away, back into the luxury black SUV that took us here. He’s taking it in quietly, but this visit to Paris is a pivotal new chapter in one of hip-hop’s most unique stories. Savage is back to Europe for the first time since he was child; until very recently, this was impossible.

Born Shéyaa Bin Abraham-Joseph in London, and raised in Atlanta from the age of seven, Savage, 31, is American by all standards but paperwork. He lived much of his life as an undocumented immigrant; for a while, he couldn’t even drive or fly for lack of a government ID. As he made a name for himself as a street rapper with real gangster bona fides and menacing wit, he had to take cheap buses up the coast to label meetings in New York.

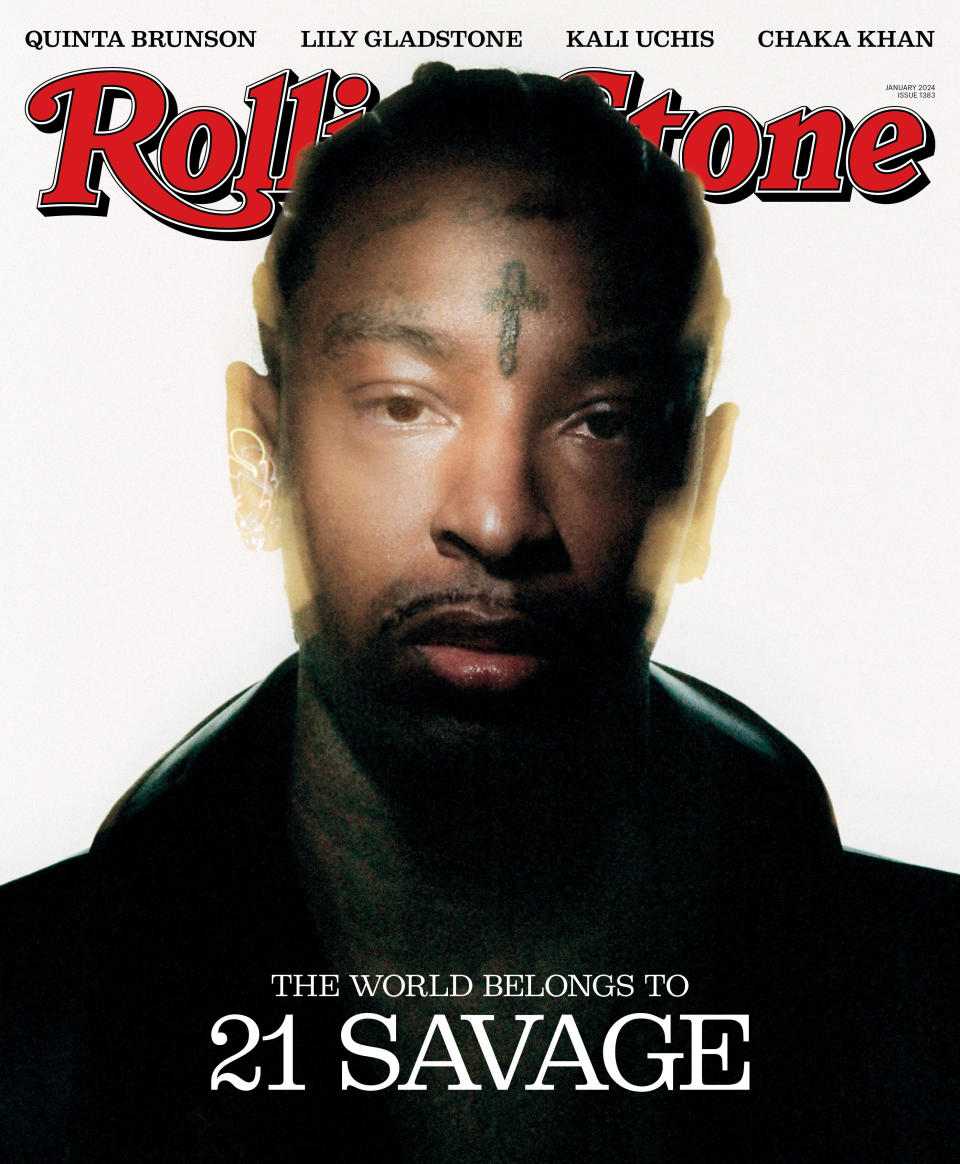

21 Savage photographed in Paris on Nov. 13, 2023, by Thibaut Grevet.

But lack of papers didn’t keep him from becoming one of the biggest names in rap. The markedly Southern, deadpan, solidly intimidating croak of 21 Savage’s voice is unmistakable. Savage used to rap in that same vein-popping squall popular in mid-2010s Atlanta hip-hop. By 2015’s Slaughter King, though, it cooled into the drawl we know today, while maintaining the kind of flippant audacity you hear on hits like Drake’s “Jimmy Cooks” (where Savage starts his verse with “Spin a block twice like it ain’t nowhere to park”). “I meant that shit more back then,” he says, laughing at his old animation.

Constantly called on by hip-hop’s finest — J. Cole, Young Thug, Future, Cardi B — Savage comes off as your favorite rapper’s favorite rapper. Drake has been a fan going back to 2016, when he crowned Savage “a young October king with all the juice right now” in an Instagram post. Thanks in part to Her Loss, his and Drake’s 2022 collaborative album, Savage was the sixth most popular artist in the country on Spotify in 2023. He’s given back, too, implementing so many community-service initiatives in Atlanta through his Leading by Example foundation that he was honored with his own day in Georgia: Dec. 21. The Young Democrats of Atlanta recently honored him with their Carry The Torch Award, recognizing “significant contributions to music, social activism, philanthropy, youth empowerment, and cultural influence.”

But his ascent was marred by shocking turbulence: Early on the morning of Super Bowl Sunday 2019, after performing at a Nike party in Atlanta, Savage was driving Meezy’s Challenger when he saw flashing blue lights and guns drawn. He was apprehended on an alleged visa violation in a targeted operation by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. “‘We got Savage,’” he recalled hearing. Savage’s lawyers contended he was singled out for his star power, as the Trump administration waged a war on immigrants of color.

Savage was jailed for nine days at what one expert called “one of the worst immigration detention centers in the U.S.” As he was arrested, he had been preparing to fly from Atlanta to Los Angeles to celebrate the sixth birthday of Kamari, the eldest of his three children. The kids were already there, waiting on him. His mom, Heather Joseph, let them know he wouldn’t be making it. Savage thinks he’ll explain the whole situation when they’re older: “When I was growing up, I didn’t know my mama problems and shit,” he says. He was jailed during the 2019 Grammys, where he was up for his first two awards — Record of the Year and Best Rap/Sung Performance for work on Post Malone’s “Rockstar,” which they had been set to perform together. He watched the awards in his room at the detention center.

Savage and his legal representatives say that after a previous visa expired, he applied for another, in 2017 — a U visa, which grants U.S. residency to crime victims who cooperate in their investigation. Four years prior, Savage survived a gruesome shooting — he took six bullets — that his friend did not, making him potentially eligible. The application was pending when he was arrested. ICE claimed that, in addition to overstaying his visa, Savage was a convicted felon, which his lawyers refuted; he only has a marijuana-possession offense to his name.

Deportation and a 10-year ban from America loomed over him. Celebrities like Kendrick Lamar, SZA, and Post Malone, as well as activists and ordinary citizens, rallied for his freedom and citizenship. “It felt good to know people was fighting for me,” Savage says. Civil rights organizations formed the #Free21Savage coalition, issuing public calls to action, rallying elected officials, and releasing a star-filled PSA. A petition for his freedom pointed to the historically underreported harassment and targeting of Black immigrants and garnered half a million signatures.

It would take years to sort through his legal situation. Finally, in October, Savage announced that he had become a permanent U.S. resident with the right to travel internationally and return. Drake himself commemorated the moment with a line on his solo album For All the Dogs: “Savage got a green card straight out of the consulate.”

The pair celebrated by taking the stage in Toronto on Oct. 7 — Savage’s first international show, and the last stop of their It’s All a Blur Tour, which Savage had played in every city (excluding Montreal and Vancouver). Savage says he had been in touch with Drake about the progress of his immigration fight: “I used to update him and shit because I wanted to do the Toronto show,” he says. But while a quick flight to a neighboring country was special, getting back to his home continent is something else entirely.

Which brings us back to Paris on this drizzly November night. Savage just arrived here to kick off a headlining tour of Europe that culminates in a London homecoming show in a couple of weeks. There are 19 of us moving around Paris together; people Savage considers family. There’s Buwop and Buck, friends who grew up near him, and Savage’s blood brother Karu, a fresh 21 years old. Then there’s 21 Lil Harold, who’s opening for Savage on the tour, and TJ, 23, who might as well be his blood brother.

“He’s just a genuinely loyal, giving person,” says Meezy of Savage, adding that it takes a lot for him to push you away once you’re close. “He’s going to try his hardest to keep his unit as tight as possible. You got to cross that man. He ain’t going to cross you.” Meezy, who has been in business with Savage since 2015, had held off on going international, only traveling to London once, on business. “I just told myself I ain’t going to travel the world until we can do it together,” he says. “‘I ain’t going to see nothin’ before my brother’-type shit.”

Later that evening, I ask Savage what was on his mind while he watched the Eiffel Tower so stoically. “Nothing really,” he says plainly. “I was just looking.” After a lifetime of only knowing it as a landmark on screens and paper, it’d be a lot to take in for most people, but I’m also reminded of something he told me days before: that he generally prefers thinking to himself to talking out loud.

“It’s like you’re free when you in your head,” he said — free of judgment, free of misinterpretation, free of consequence. That stoic exterior, though, belies a trove of curiosity, a soft heart, and a lifetime of resilience, not to mention one of rap’s more-revealing testimonies to the peril and promise of the so-called American dream.

AHEAD OF OUR TRIP to Paris, I first meet Savage at Doppler Studios, an Atlanta mainstay where luminaries like Outkast and TLC have recorded. His room looks like it could host at least 100 people, but on this Tuesday night, about 10 folks rotate in and out of it. Meezy is a constant; so is Savage’s longtime A&R Jennifer Goicoechea, who says she realized he was a superstar when, at his first solo headline show in 2016, Savage had the Atlanta venue completely blacked out, with blood-curdling screams blasting through it for his entrance.

When I walk in, Savage’s face is poking out of a ski mask. He’s wearing an olive Nike Tech fleece, with his legs kicked up on the studio’s slick, wooden center console, one white Air Force at the bottom of his gray joggers, the other foot in just a sock. He’s here finishing up his next solo album, but he’s reluctant to divulge details. “We ain’t got no mixes back yet,” he says when I ask if I can hear a bit of what he’s worked on so far. “He damn near don’t even like the fact that we be listening to it, and I’m his manager,” Meezy adds. “That’s why he said it is not mixed. It might sound small, but it’s a really big deal for him.”

The seminal producer Metro Boomin, who’s worked with Savage over the past decade, helped with the new music, even as they both had other blockbusters on their hands. “I got a studio in L.A.,” Metro says. “We would work on the verses for [Heroes & Villains, Metro’s hit album from last December], and at the same time, I feed him beats when we work on the stuff for his album, and he was working on Her Loss in the front room at that time, too.”

Savage spends a lot of time in the studio; it’s one of two places he tends to find himself. “I just go to the studio, go home,” he says. He can’t really hang at any Atlanta haunts anymore — he’s too famous for that. Does that feel limiting? “Nah, I love being at home. Home is fun to me.”

His three children have a low tolerance for their father’s fame, he says. “They hate when people try to ask me for pictures,” he tells me. “They’ll argue with each other: ‘Hurry up before they start trying to take pictures with Dad. Let’s go.’” Kamari is 10 now, and Savage has two eight-year-olds — a son, Ashaad, and a daughter, Rhian, who wants to be an actress and has already begun taking lessons. All of his kids like sports, and he loves taking them to the trampoline park. He doesn’t play or discuss his music with them, he says, and they’re not particularly interested in it, either. “My daughter would just be like, ‘Make a song about me,’” says Savage. “But other than that, nah.”

Though Savage is now free to travel the world, his people remain the center of his. “When I lost my mom, God bless her soul, he came over to my house with my brothers and sisters,” Metro says. “Even while I’m over there just crying or whatever in the other room, he over there talking to my grandma for hours. None of that has anything to do with making an album. You feel me? But all that stuff counts.”

Savage’s schedule switches up often, but lately, in addition to spending time with his kids, it involves riding motorcycles through Atlanta (Biker Boyz happens to be his favorite movie), hitting the studio in his premium work hours of 8 p.m. to 1 a.m., then playing NBA 2K. He often goads friends like Landstrip Chip, another artist in the studio with us, into playing with him before getting an impressive seven hours of rest (“Hell, yeah, I’m going to get my sleep,” Savage says proudly). He says 2K grounds and relaxes him, as does Spades. He asks me, out of the blue, if I know how to play. “No, I don’t,” I respond. “Why?”

“So he can take your money. Leave him alone!” Meezy interrupts. “You’re going to lose every match.”

At Doppler, Savage tells me that his music is “fiction as hell.” “I just think of it in my head,” he says. “Some of it be based off of real life, but a lot of it be creative stories.” All great works of fiction are rooted in reality, though. One of the triumphs of Savage’s “A Lot,” featuring J. Cole, which won them the Grammy for Best Rap Song in 2020, is the way he boils his lived experiences down to universal truths: A lot of people cause harm. A lot of people die.

Savage sold hard drugs, he told Fader in 2016. He’s robbed people, a friend of his told the magazine. Though they’d try to ensure the properties they hit were vacant before clearing them out, “sometimes we had to shoot our way out,” the friend said.

He’s also suffered deep losses — among them, three brothers. Two were biological kin, both younger than Savage, the eldest of 10 siblings. In Atlanta, his brother Quantivayus “Tayman” Joseph was killed in 2014, reportedly in a botched drug deal, inspiring the dagger tattoo on Savage’s face. In London, his brother Terrell Davis-Emmons was stabbed to death in 2020. One brother was chosen family. Known as Johnny B, he was killed on 21 Savage’s 21st birthday, Oct. 22, 2013. Savage was with him and got hit six times himself. He thought he might die, too, but managed to call 911 with just one working hand after unsuccessfully knocking on a nearby door.

He only began celebrating his birthday again recently. “I got shot on my birthday, and I got into a car accident with my mama on my other birthday,” he tells me. “So I always felt like my birthday was cursed or some shit. I just used to sit in the house on my birthday every year.” He now has an annual blowout in Atlanta — Freaknik-themed in the past, and early-2000s-themed this year.

Savage says his music is “fiction as hell. Some of it be based off of real life, but a lot of it be creative stories.”

Though violence has been a recurring motif in his life, he’s also actively denounced it. He’s talked to students in an anti-gun program, spoken out against shootings in his vicinity, and tweeted “Atlanta We Have To Do Better Put The F****** Guns Down !!!!!” in 2022 — to which people responded by implying he was being hypocritical, tweeting his lyrics, like “Shot that nigga 20 times, damn, this nigga lucky,” back at him. “A Song Is For Entertainment It’s Not An Instruction Manual On How To Live Life In Real Life I Give Away A lot Of Money And Spread Financial Literacy To My Community Stop Trying To Make Me 1 Dimensional,” he responded.

In a quiet moment in the studio, Chip says, “We got it so good over here,” after watching a clip of a rocket being launched; Savage asks if it’s from the Israel-Hamas war. I ask Savage what he thinks when he hears sentiments that we’re better off, knowing the carnage that has touched him right here in Atlanta.

He can’t quite wrap his head around what he’s heard about the war. Without naming a side, he says, “I could never be that coldhearted, though. Even the person that just greenlights that — the person who says, ‘Yeah, you got to drop a bomb on that shit’ — how could you sleep at night knowing you just dropped a bomb on 40 kids?” He’s not referring to any particular incident, and like many people, he has a surface understanding of what’s happening, though he wants to learn more. He asks about the origins of the conflict and looks up the region’s geography on his phone.

When Savage is finally ready to record at Doppler, he slips into the left-most corner of the wide booth, out of sight for most people in the room, and sits on a stool in complete darkness. He can only be heard through the headphones worn by his recording engineer, Isaiah, at the desk. Up to his second album, I Am > I Was, Savage would let the whole room hear him, but now he prefers his privacy. “I think back when it started getting more like a job, I got like that,” he says.

With Savage in the dark, I can ever so slightly make out his silhouette leaning on the chair, his waist at the edge of its seat. I can see the light on the slim, steely vape that’s almost perpetually on his person. When he’s rapping — freestyling and punching in, here, he tells me later, though sometimes he writes out lyrics — he sits on the stool and swivels himself gently, his hands ticking slightly. Otherwise, he’s still.

Goicoechea, his A&R rep, offers me her headphones to listen in. The beat is easy-listening trap, if you will. He’s working out the kind of bars of his I love over it — curt, quippy, unvarnished, and darkly funny. “I got turnt, now I’m the chosen one,” he plays with. “I ain’t have no car, I stole me one.… Where my opps at? Nigga, show me one.”

When I see Savage next, he’s done recording, and his face is bundled in his ski mask and fleece hoodie. “She can hear this song,” he instructs, much to my surprise, as Isaiah cues it up. Savage hits some catchy singsong-y melodies on it, but naturally, raps about sex, clothes, and get-back, as he is wont to do. He employs coital lore that doing the do has made his partner’s butt bigger; he brags on an expensive pair of leather jeans; he warns that the last person who got too big for their britches ended up like a certain friendly ghost. It may sound like standard rap fare, but Savage is gifted at making it leaner, meaner, and more clever.

When I tell Savage I admire his sense of humor, he asks, “If I’m serious, but you think it’s funny, am I funny?”

IN PARIS, AS WE DRIVE away from the Eiffel Tower in the SUV on stone roads dense with old buildings, Savage remarks that the city doesn’t look that different from New York — just wider streets. This, in turn, brings up memories of the tight roads in his first city — London.

His most vivid memories from there are set at his two grandmothers’ houses. His mom’s mom has passed, but his dad’s mom is still alive. The only plan Savage has set for his personal time in London is visiting family, particularly his grandmother, whom he hasn’t spoken to in a few years. Savage knows she still lives in Brixton, as he did. “I ain’t told her,” he tells me. “I’m just going to pop up.”

His father’s family immigrated to London from Saint Vincent, an island in the Caribbean between Saint Lucia and Grenada. Brixton has historically had a large Afro-Caribbean population, after a rush of immigration in the 1940s and 1950s, and saw race riots over anti-Black policing in the 1980s and 1990s before becoming more gentrified in recent years.

I got shot on my birthday, and got into an accident my other birthday. I felt like my birthday was cursed.

Savage was largely raised without his father, but he’s close to his mom, who will return to London with Savage for his show. She’s from East London, where Savage spent time as a child as well. Her family is from Dominica, another Caribbean island. “My granddaddy spoke French,” Savage tells me, “broken French.” When I ask why, Savage pulls up the ugly, exploitative history of French (and English) colonization on his phone, noting that Dominican French Creole became the common language.

His mom and an older cousin taught him a bit about their Dominican culture. “We got indigenous people there, villages and shit. She got a whole documentary on it,” he says of his cousin, whom he thinks of like an auntie. His mom’s cooking kept them close to Dominica. “It’s like Jamaican food,” he explains.

Savage says his mother moved him and his siblings to the U.S. in search of a better life. They didn’t necessarily find it, and young Shéyaa grew up amid poverty and violence. “I think it was the same shit [as London], really,” he says. Savage often raps lovingly about his mom, and I ask him when, as a child, he remembers her being proud of him. He tells me that, in the fifth grade, he won a spelling bee; he remembers acing some math competitions, too. She was always happy with him, he says, despite the difficulties.

Shéyaa found his way into illicit money around the sixth grade — selling a little weed — to pay for his own cellphone. Around the same time, at age 12, he made friends with a boy called Skiney, who was killed in 2021, he tells me. Skiney lived below him; they’d rap and make up songs.

Years later, at about 18, Savage came into big money in the streets, and he put it toward studio time. “I had hit a lick for like $80,000,” he says. “Me and my partners, we split it four ways. I already had a little money just from hustling, then had an extra $20,000, so I was just trying shit.” The name 21 Savage, he has said, represents the 2100, a Decatur gang he was affiliated with; a former propensity for theft and shooting; and the deaths that came with that life.

As Savage put more stock into rapping, he found a manager, Kei Henderson, and sent what would become his breakout song in Atlanta, “Picky,” to one of the city’s hottest club promoters at the time — Meezy, also from Atlanta’s Eastside. “He wasn’t really fucking with it,” Savage told me at the studio, with Meezy listening in. “He wasn’t really responsive like that.”

“Don’t let him act like he was just a rapper following his dream, man,” says Meezy, on light defense. “To me, he wasn’t a rapper. He was just a nigga who made a hard song from the street.” Soon, though, Meezy became a fan, then co-manager, and in 2019, Savage’s sole manager.

Savage’s shift out of the streets was gradual. “I never really stopped doing my thing until the music just took off,” he says. “It consumed my time, so I didn’t have time to do nothing else. I was getting booked. I seen it working. Once I seen it started working, I started just putting more of my all into it.”

Savage met Metro Boomin around 2013. “Before we got close, I’d just be like, ‘Hey, that’s just the nigga that smoke cigarettes and look mean all the time and don’t talk,’” Metro says. “He ain’t ever seemed that approachable of a person. I mean, he’s still like that pretty much.” (Metro does say that Savage has softened some with age, success, and parenthood.)

In 2014, Savage approached Metro with a request. “He was like, ‘Yo, I’m going to start fuckin’ with this rap shit. You send me a couple of beats or something.’” One of them became “Drip,” on Savage’s first mixtape. It was the start of a very productive friendship. “I always loved making dark and ominous beats,” says Metro. “So it was like a match made in heaven, with how cold and eerie the beats I was giving him, on top of how he would rap, the shit he was saying, how crazy it would be. There was still beauty in the beginning of him not being a professional rapper or just knowing everything about rap. That’s what made him so different and unique.”

They decided to make a collaborative tape. Metro remembers the two of them in a shitty Austin studio during South by Southwest, cranking out Savage Mode fan favorites “Bad Guy,” “Mad High,” and “Ocean Drive” in one sitting. They chipped away at Savage Mode for two years before it was released in 2016, setting Savage on the path to stardom.

Seven years and billions of streams later, Savage is at the pinnacle of his career, though not exactly obsessed with the spoils of stardom. The 2024 Grammy nominations were announced while we were in Paris, with Savage racking up a career-high five nods, including Best Rap Album for Her Loss. Three days after the nominations were revealed, Meezy tells me he and Savage hadn’t discussed them yet.

THE SUV HEADS to Arthur Kar’s L’art de L’Automobile, an exclusive club for luxury-car enthusiasts. When I ask who, exactly, Kar is, Savage tells me “he’s the man in Paris,” calling back to Kar’s guest voice-over on “On BS,” a Her Loss song where Kar flexes against fashion week and flaunts his fast whips. Turns out Kar is also a fashion head and friends with Drake; Savage met him on the It’s All a Blur Tour.

On the way over, Savage watches videos on social media. At one point, Drake’s “Calling for You,” on which Savage is featured, blares from his phone, soundtracking a clip about clothes.

Savage shows Buck and Buwop a meme he finds on Instagram about the pack of orange combs with which many Black folks are familiar, then asks us if we know the real name of an R&B classic that he plays aloud. 21 Savage is a soul connoisseur; there’s even an Instagram account dedicated to compiling clips of him singing to himself: songs like “Hrs & Hrs,” by Muni Long, and “Promise,” by Ciara.

The song Savage quizzes us on is Ginuwine’s “Differences.” Buwop hits the ad-libs, but is stuck on the name. So is Meezy. After playing Name That Tune, Savage sings along to a cover of Joe’s “I Wanna Know.”

Savage got out of the streets gradually: “I never really stopped doing my thing until the music took off.”

Buwop wonders aloud why men in R&B don’t serenade women like they used to. “Y’all bitches some hoes now,” Savage retorts with reflexes of a stand-up comic. “Nobody singing to y’all. Everybody sell pussy. Ain’t nobody to sing for.” We all laugh — me mostly due to his quick delivery and light tone, though attitudes like this can be concerning. Every woman is obviously not a sex worker, but sex work doesn’t make one unworthy of love. As ordinary women sexually empower themselves, women in rap succeed while flipping hip-hop’s misogynist script, and as everything from dating etiquette to reproductive rights becomes a battleground, the gender wars have gotten the messiest they’ve been in my lifetime.

Savage has his own questionable outlooks on gender. When I ask him what his friendship with Drake is like, he says, “I feel like describing male friendships is zesty as hell.” That there could even be something feminine or gay (as “zesty” can read as derogatory slang) about articulating the details of a male friendship speaks to the stigmas, taboos, and expectations that isolate men and stifle their expression. I say as much to Savage.

“There are these unneeded parameters around men and the way we expect them to express love or care or friendship,” I propose.

“It’s needed,” says Savage. “That’s what separates men from women.” He tries to explain that gender norms are useful; emotional outbursts, he says, as an example, should be reserved for women, while men should approach conflict with “logic.”

“Like in the argument, a man’s supposed to think more about what he say,” he says. “I feel like a woman is supposed to cry, like, ‘Fuck this shit.’”

Buwop agrees. “The man and the girl can’t be emotional,” she says. “You have to give the girl room to be emotional.”

Their point is that these gender roles create balance, but I say that both people in a relationship can work to achieve balance in themselves to bring balance to the unit.

“I get what you’re saying, but I don’t agree with it,” says Savage before a correction: “Well, I agree with most of what you’re saying. I just feel like the man supposed to be one way and the woman supposed to be one way.” He acknowledges that we could have this debate all day, but leaves it there.

“The only weak spot I think I got is women,” he told J. Cole in a viral clip. “I think the toughest niggas is the softest niggas with women.” In 2017, he dismissed online critics who took aim at him for supporting his then-girlfriend Amber Rose’s SlutWalk, an annual protest she held against gender inequality and sexual violence. He held a sign that said “I’m a hoe, too,” and defended it when the wisecracks inevitably came.

There are love songs throughout his discography — some on heartbreak, like “ball w/o u,” but several rather reverent, like “FaceTime,” “Special,” “out for the night,” even “Spin Bout U,” with Drake. But his music can also be salted with a dash of the objectification commonplace in hip-hop — as fans, women learn to swallow it — and as successful as Her Loss has been, the album faced critiques of cruelty, especially leveled because it’s where Drake had most virulently tossed aside his own lover-boy image to taunt, degrade, and vilify women. Savage has been asked about the album’s most jarring moment, on “Circo Loco,” when Drake rapped, “This bitch lie ’bout getting shots, but she still a stallion.” It seemed to obviously reference Megan Thee Stallion’s shooting at the hands of Tory Lanez.

He’s said he generally encouraged Drake’s candor on the album, but talking to Complex — which named him the best rapper of 2022 — he got more specific: “I don’t feel like that was his intention [to diss Megan],” Savage said. “Remember when I said I was telling him to not hold back, people tried to twist that to make it seem like I was talking about that situation. That bar was more of, like, a joke bar than him trying to say something about her. But I don’t really like speaking on people’s situations because life be real.”

THE DRIVER MANEUVERS the SUV through a nondescript garage door and down a slope, at the bottom of which Kar meets us. Three of the four levels in the building he occupies start on the 10th floor, so the 19 of us take a winding walk upward until we reach his assortment of Porsches, Ferraris, and Mercedes-Benzes. Kar and Meezy make loose plans for a music-video collaboration between Savage and L’art, but this meeting feels more like play than work. Savage and his massive crew almost look like schoolkids on the field trip of the year, gingerly exploring the scores of vehicles across the grounds.

An amusing motif in Savage’s music is the 12-car garage he’s rapped about, so I ask Savage how big his garage really is as he checks out a model of KITT, the black Pontiac Trans Am from Knight Rider. (He has the same kind of car in red, though his is a 1979, about a decade older than this one.) After a moment of consideration, Savage says his garage can probably fit 10 cars.

“That nigga got way more than 10,” inserts Meezy. “I don’t even know how many he got.”

“So where do you keep the rest of them?” I ask.

“Everywhere,” Savage says.

“And he not even joking,” Meezy adds. “Just different areas that he trusts. I bought him a car for his birthday — it’s still at the studio.”

Savage spots Kar’s two rare motorcycles across the room. The first is a Ducatti Panigale V4 S Corse, a limited luxury bike running around $30,000. Savage has a Panigale V2 back home, a slightly newer version. The other is a Ducati 998, a working model of a bike from The Matrix Reloaded. Savage mounts the Panigale, revving the engine loudly. “I like that,” he says, satisfied, after cutting it off.

THE NEXT TIME I see 21 Savage, he’s thrilling a sold-out crowd at Paris’ Zénith Arena. His show begins with a white cloth backdrop across the stage. The air swells and ripples the fabric as headlines on Savage’s ICE arrest fill it; next, footage of European flags and streetscapes takes over. “This is our city,” says Savage, a disembodied narrator, not yet onstage. From the moment he emerges, two spotlights tail him and the background morphs into the Stars and Stripes, waving slowly.

The crowd erupts when Savage emerges, rapping the first words of “Runnin’,” from Savage Mode II. As the set goes on, a story unfolds. A stage-length screen behind Savage shows vignettes of the life of a young Black boy who, at different points, rinses blood from his hands, runs through the streets in a frantic blur, and looks lost in the dark. The boy looks nothing like Savage, but endures the kind of struggle, danger, and violence we know he has. It isn’t all bleak; there are lively graphics interspersed, like a meter measuring the freakiness of the crowd during “10 Freaky Girls.”

Yet, as we come in and out of the boy’s POV, the audience is confronted by a pitbull; later, a wall of nightmarish eyes. Throughout the show, a CGI home goes from trap-house commotion — the flash of police lights reflected from the windows and the clamor of disarray filling the air — to an idyllic suburban house, with birds chirping, thriving rose bushes, and an American flag draped from it.

For the tour, Savage hired creative director Ben Wolin, alongside show director Matt Bauerschmidt and creative consultant Danny Seth. Wolin says Savage will explore the motif of the American dream over the next year, though they realize some of the themes apply the world over. They decided to use Savage’s global moment to tell a universal story of the dark underbelly of dream-chasing and the turbulent path to a peaceful life. “We pulled a lot of references from Savage himself,” says Wolin.

Paris is elated to spend the evening with him. There’s camaraderie and ease, with barely any security workers visible. As the night ends, he thanks the audience for being his first stop around the world.

LONDON IS THE LAST STOP, for now. There, Savage makes a slightly different entrance: This time, he’s revealed to be behind the white curtain after it plummets to the floor. “London, make some motherfucking noooooooise!” he commands before offering a much cooler “I’m back, bitch.” He two-steps to “Who Told You,” by British rapper J Hus, who pops up to perform the song. Savage later plays the ultimate hype man to London’s latest rap sensation, Central Cee. Then, hearkening back to his Caribbean roots, he hits a smiley sway when dancehall star Popcaan pops out, too.

One of the first things Savage did when he touched down in London was, in fact, visit his grandmother, who was still in the same council estate that he remembered. “She was shocked,” he tells me. “She started crying.” He visited twice, the second time bringing his kids, who took warmly to the great-grandma they’d only ever known from phone calls. He found time to shoot a music video in Brixton as well. He says the area looked exactly as he remembered it.

Savage’s mom, Heather, joined him on the trip. They took the kids to Windsor Castle, and dabbled in magic at a tour of the Warner Bros. studios where the Harry Potter films were made. In his own moment of play, Savage was spotlighted on the sidelines of London’s Arsenal Football Club, where he beamed and waved the custom jersey he was presented with.

His kids told him they had fun and can’t wait to go back. Neither can he, and he says it won’t be long.

“What did it feel like?” I ask him over Zoom a few days after the London concert, while he’s settling down at home in Atlanta. “It probably was my most, what’s the word…?” he says, pausing for a beat. “Passionate show.”

Savage thinks he and the audience shared something special. “I want to thank each and every one of y’all for buying a ticket to come see me,” he had told them before the night ended, also announcing he had an album on the way. “I went through a lot of bullshit to make it on this stage tonight with y’all.”

Photography direction by EMMA REEVES. Produced by DIVISION: GWENDOLINE VICTORIA, Head of Fashion Films and Content; ANNE-SOPHIE DUJON, Senior Project Manager; RÉDA MADJID, Project Manager; MATEO MURGA, Line Producer. Hair by YANN TURCHI for BRYANT ARTISTS. Makeup by LINDZY. Styling by FATIMA B. for MASTERMIND MGMT. Tailor: GUILLEM RODRIGUEZ. Set Design by FELIX GESNOUIN for TOTAL WORLD. BTS Videographer MARIA KRYVOBROK. BTS Editor SASHA FOX. Lighting Director: HARRY HAWKES. Photographic assistance by KINU KAMURA and ROMAIN JOUVIE. Digital Technician: THOMAS PORTEVIN. DIVISION production assistance: KENZA HASSAN and EMMANUELLA TETTEH. Styling assistance by ROUGI. Set design assistance by PALOMA LARATTE and GUSTAVE BIRCHLER. Unit Manager: DEJAN TRAJKOV. Production assistance by JULIEN FERNANDES.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ settings: { plugins: { pmcAtlasMG: { iabPlcmt: 1, } } }, playerId: "4d2e11b7-633a-417a-962e-4b7e105b5998", mediaId: "5e6ec1d7-0fba-40dc-9e35-14e51ba57dd6", }).render("connatix_contextual_player_5e6ec1d7-0fba-40dc-9e35-14e51ba57dd6_1"); });

Best of Rolling Stone