In 2022, Hollywood played itself to excess — but to what end?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Why is Hollywood so obsessed with itself?

It's a fitting question for 2022, which saw the release of several projects that turned their gaze inward. They ranged from luminous (Ethan Hawke's six-part documentary The Last Movie Stars) to polarizing (Babylon) to self-mythologizing (The Fabelmans) to downright solipsistic (Blonde).

It's not as if Hollywood's need to interrogate itself is anything new. The impulse is so frequent, one could argue it verges on narcissism. Nearly as long as there have been movies, there have been movies about movies (see: several iterations of A Star Is Born, 1932's What Price Hollywood, Sunset Boulevard, The Bad and the Beautiful, The Player, and more).

Scott Garfield/Paramount; HBO MAX; Netflix

But in 2022, the navel-gazing reached new levels of meta pastiche. Perhaps during the COVID lockdown, creators had more time than ever to think about themselves, myth-making and the cost of fame. Hollywood has always been more about legend than reality, more reel than the real. It's the home for those who live by A Streetcar Named Desire's Blanche DuBois' credo of not wanting realism, but magic.

Though stories about the entertainment industry are a reliable presence, the exact forms they take continue to surprise. One of pop culture's most enduring figures, Elvis Presley, received a 2022 biopic, but Elvis was barely interested in his period as a movie star, glossing over his 31 feature films with a brief montage (a blip in the nearly three-hour runtime). Presley's own razzle-dazzle musical persona was a far greater performance than anything a studio ever tasked him with.

Warner Bros. Pictures Austin Butler in 'Elvis'

But what about the 2022 projects that did confront Hollywood and moviemaking with more than a passing interest? Though they all fixate on different aspects of Hollywood history, they are works obsessed with deconstructing their subjects, exposing the "truth" behind the myth, only to create a new legend in the process.

Some of them were purposeful (and those projects tended to be the most successful). Double profile The Last Movie Stars tells the story of Golden Age icons Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward, and their legendary marriage, using their own words and those of friends, collaborators and confidantes. With access to previously lost transcripts, director Hawke and the Newman family offered audiences an unprecedented view of their lives.

Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward, circa 1965

But Hawke didn't settle for a traditional documentary with talking heads and slow zooms into black-and-white photographs. He recruited modern actors to play Newman, Woodward and their contemporaries by reading their transcripts, an act which inscribes a mythology onto the project without even trying. Hawke also included long Zoom conversations with his friends and colleagues, digging deep into the acting process, fame, and what propels a person to be an artist. He tries to answer these questions for himself through the lens of Newman and Woodward's life, thereby telling their story and using it as a map to try to get at what it means to lead a nobly artistic life.

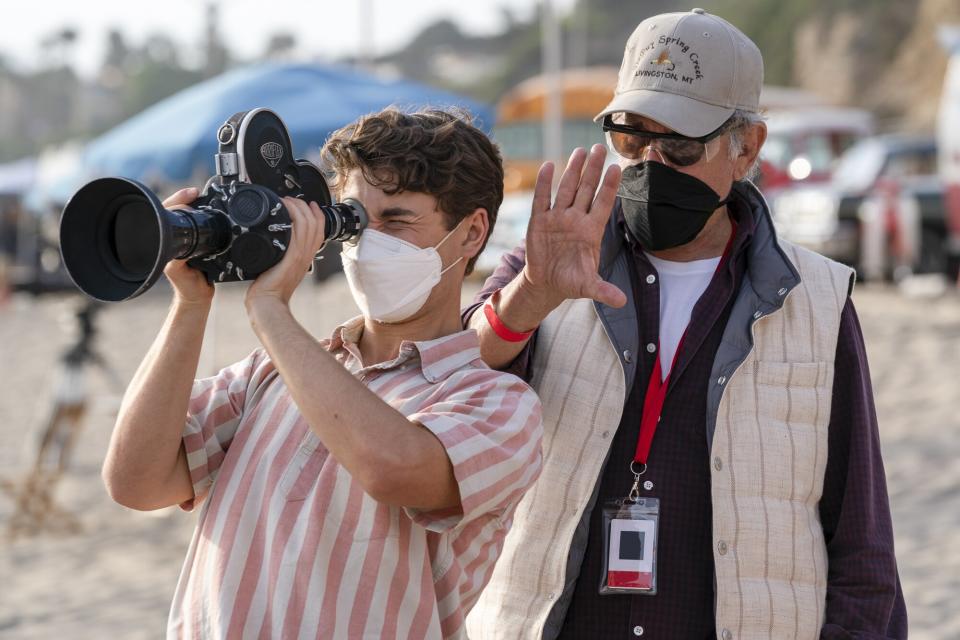

It's a similar subject that sits at the heart of Steven Spielberg's The Fabelmans, a movie which isn't about Hollywood in the strictest sense. Hailed as Spielberg's most personal film, it delves into the adolescence of Sammy Fabelman (Gabriel LaBelle), a stand-in for the young director. We see the ways in which film touches his life, how his obsessions with it become both all-consuming and a valuable lens through which to understand his family.

Merie Weismiller Wallace/Universal Pictures and Amblin Entertainment

Spielberg has always had a touch of fairy-tale wonder about him, and The Fabelmans casts that spell over his own family, as evidenced in the film's fictional surname, invoking the idea of a fable, a form of storytelling that uses the trappings of myth and the fantastical to convey a deeper truth or lesson. The Fabelmans toes a delicate line, treating the adults in the film with a rich humanity that is also striking in its clear-eyedness. All the while, it spins a yarn about the ways in which films grab hold of us, shake us up, and become our modern-day myths.

Spielberg (working with co-screenwriter Tony Kushner) exposes the crucible of love, resentment, and frustrated creativity that gave birth to his artistic self, while mythologizing it at the same time.

Babylon and Blonde want to pull back the curtain on a more lurid version of Hollywood history (whatever amount of actual history there is to be found). Both present a debauched industry that runs on drugs, sex, and excess.

Babylon is, unlike Blonde, visually compelling and expertly composed, with breathtaking sequences that serve as a powerful reminder that the movies are first and foremost a visual medium. It's a tragic portrait of Hollywood in a moment of transition, and a chilling nod to the precipice we stand on at this very moment, economic models in question.

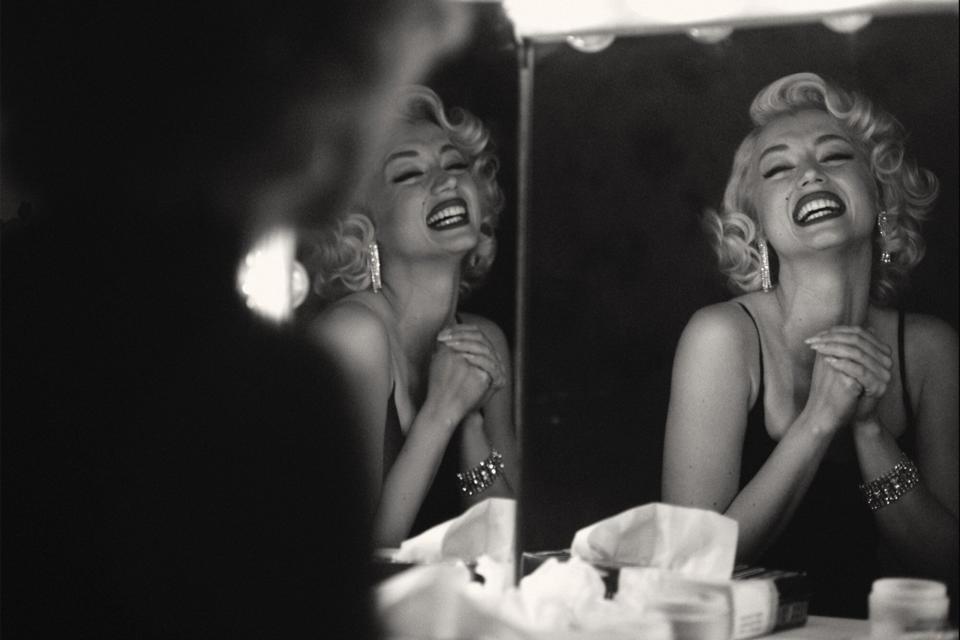

Netflix Ana de Armas as Marilyn Monroe in 'Blonde'

Blonde is far more cruel and ill-intentioned in its approach, selling audiences a narrative about the abuse Marilyn Monroe (Ana de Armas) endured by doing her the indignity of exploiting her further. It wants us to understand that Marilyn Monroe is a myth and Norma Jeane Baker is a human being, but in the end, it dehumanizes both sides of the same woman, trading on hearsay and gossip throughout without ever approaching any level of the intelligent commentary it thinks it possesses.

In contrast, Babylon is a cacophony of themes and stories, but it's more interested in pouring Kenneth Anger's Hollywood Babylon tales in a cocktail shaker and seeing what comes out. Some of the stories that emerge are marvelous — the contributions of women directors to silents; the grueling and dangerous work of the early sound era — but its parts are greater than the whole.

Babylon bombards us with narratives, visual gags, bodily fluids, and Justin Hurwitz's stirring speakeasy-worthy score. In its final sequence, it pays homage to the power of cinema via Singin' in the Rain and heaps of other film footage in a dizzying montage. The relationship between movies and the audience is held in reverence, even if nothing else is.

Scott Garfield/Paramount Pictures Nellie LaRoy (Margot Robbie) is carried aloft during a big-scale Hollywood production in 'Babylon.'

But Babylon can't really decide if it wants to critique or celebrate the dream factory. Does it hold Hollywood in reverence or in contempt? Director Damien Chazelle has argued that he hopes to indict the system while championing the art form, but I don't know if the movie itself even truly knows what it wants. Like the silents themselves, Babylon's images are more powerful than anything it has to say.

No matter what form the critique or celebration takes, there's still one major question: Why, in 2022, when there are more screens of varying shapes and sizes vying for our attention than ever, are storytellers still so consumed with Hollywood as a concept?

Perhaps the answer lies in the massive upheaval the industry is currently facing, as the streaming bubble bursts, historic studios are plagued by destructive CEOs who privilege "content" and the bottom line over art, and we're all left wondering what will still be standing when the smoke clears?

Revelatory or repugnant, these projects all have one thing in common — the central figures of their stories didn't do it for the money. Maybe they did it for something as grubby as the fame, which is arguably a twisted hunger on a grander scale. But above all, they did it because they had to. Something grabbed a hold of them and tore until they yielded to the power of cinema, as institution, industry, and art form.

In a moment where the very concept of cinema and Hollywood lacks cohesion, perhaps all filmmakers can do is hold up a glass as it shatters, and hope that the cracks in the reflection show us something we couldn't see before.

Babylon and The Fabelmans are now in theaters. Blonde is available for streaming on Netflix; Elvis and The Last Movie Stars are both on HBO Max.

Related content: