We're all kinda fine with DRM now

You can't spell drama without DRM.

Digital Rights Management. The phrase alone, or just its abbreviation, DRM, once had the power to spark scathing editorials and spawn furious debates in online forums worldwide. In the 2000s, major PC video game publishers began adding software to their discs that limited the number of times these games could be installed, tracking and verifying players in new, conspicuous ways. Variations of this system persisted throughout the early 2010s, when Microsoft attempted to release the Xbox One with built-in DRM checks. The response from fans was so vicious that Microsoft abandoned its strategy and rebuilt the Xbox One without DRM just months before its launch date.

Fast forward to February 2020. NVIDIA launched GeForce Now, the first and only cloud gaming platform to operate on a "DRM-free" basis. When you buy a game via GeForce Now, you get to keep it, regardless of whether the service itself remains live -- a promise that its competitors, Google Stadia and Microsoft's xCloud, can't make.

Yet, no one seems to care.

In heated Twitter threads and editorials about the newest and most controversial gaming platforms around, the DRM-free bit of NVIDIA's news seemed to barely register with fans. A feature that would've made headlines in 2010 is often relegated to a single sentence at the base of the inverted pyramid, or not mentioned at all.

That's because, over time, we got used to DRM. Every major gaming platform today relies on DRM, with companies like Valve, Epic Games, Microsoft, Sony and Nintendo owning players' libraries in some form. In a digital-first ecosystem, it's just easier this way.

Players weren't so agreeable when it came to SecuROM, the granddaddy of DRM. Publishers started using the anti-piracy software in earnest around 2007, when physical discs and midnight GameStop release parties were all the rage. SecuROM was a flashpoint of controversy particularly in the launches of BioShock, Mass Effect and Spore, limiting the number of times these titles could be installed and forcing players to routinely connect to the internet for authentication. By 2010, Ubisoft was pushing always-on DRM for games including Assassin's Creed 2 and Splinter-Cell: Conviction, requiring players to maintain a constant internet connection, even for offline play. Ubisoft's approach to DRM routinely broke the games it was built to protect and the response from players was unanimously negative.

Players called SecuROM punitive and hostile, and wondered why they needed an internet connection to play these games offline. EA, 2K, Ubisoft and other publishers tweaked their anti-piracy systems in response to mobs of criticism. Spore publisher EA faced a class-action lawsuit over the game's SecuROM features.

Meanwhile, Valve was building out Steam. The storefront was initially designed to streamline the patch process for games like Counter-Strike, and also make it easier for Valve to implement anti-piracy and anti-cheat measures. Steam was built to be a DRM machine.

Valve made Steam a requirement in 2004 with the launch of Half-Life 2 -- anyone who wanted to play the game, even those with physical copies, had to launch the client first. Players balked at the move, but Half-Life 2 had enough hype to sustain this plan, and Steam continued to grow. As Valve added dozens and then thousands of third-party games to its store over the years, the company implemented features like offline play and Family Sharing to assuage fans that had been burned by bad DRM practices.

Valve is too big to fail.

More importantly, Steam made buying games easy. Instead of picking up discs and typing out long CD keys, Steam offered one-click access to a massive lineup of new releases and old classics. Players bought into this online-first system entirely, and today, Steam has 1 billion registered users and 90 million monthly active players. Despite determined competitors like GOG (a longstanding DRM-free gaming hub) and the Epic Games Store, it's the undisputed leader in digital distribution.

Steam still runs on DRM. Even in offline mode, players still need to connect with the Steam client to launch any of their games. As it stands, if Steam shut down today, everyone's libraries would become instantly unplayable.

Generally, users are OK with this threat -- after all, it's Valve. It's the company that made DRM palatable in the 2000s. It's the multibillion-dollar corporation led by benevolent nerd king Gabe Newell. It's the studio behind Half-Life, Portal, Dota 2, Left 4 Dead, Team Fortress 2 and Counter-Strike. Valve is too big to fail.

As someone who entered college at the height of the Great Recession, that phrase still sends shivers down my spine.

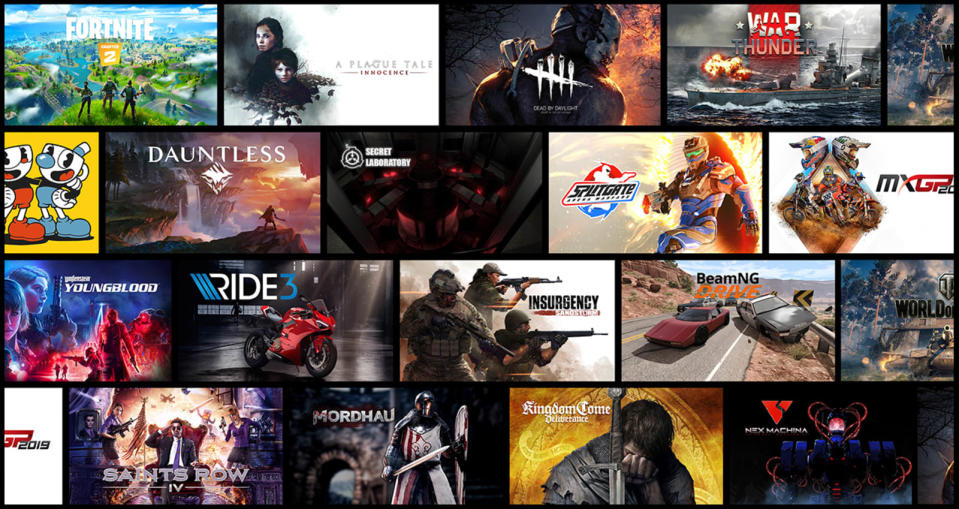

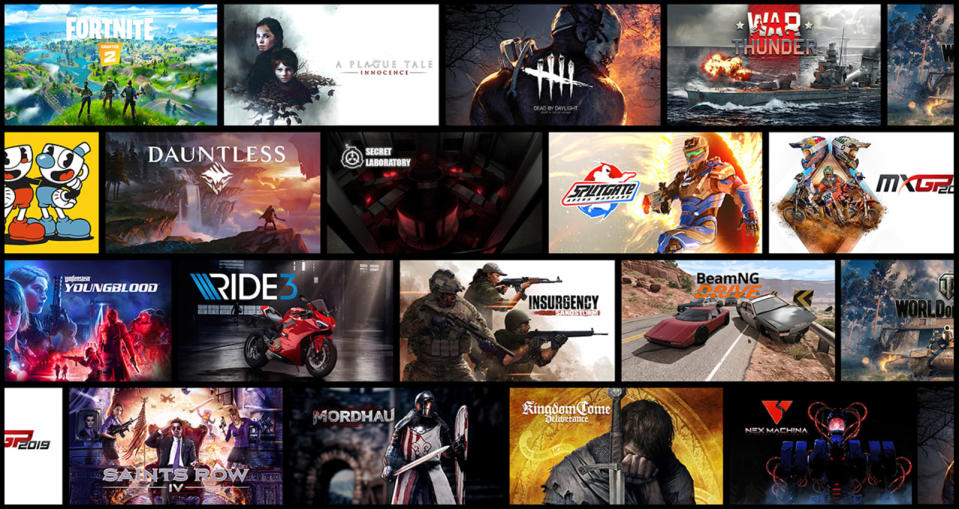

Steam offers the clearest example of how DRM quietly infiltrated modern gaming systems, though it's not the only storefront to operate in this way. Microsoft and Sony each offer subscription packages -- Xbox Game Pass and PS Now -- that allow users to purchase and play games, though these titles are only available as long as the subscription is active. The Epic Games Store doesn't have an overarching DRM policy, but many of its games, including Fortnite, require the client to launch. In cloud gaming, Google Stadia allows players to purchase any titles they want, but they're only accessible through the app, with a valid subscription and internet connection.

And then there's NVIDIA. GeForce Now is not only a game-streaming service, but it allows players to actually download games and play them locally. The store itself is DRM-free, though there is one caveat: Downloaded games end up in players' existing accounts on Steam, the Epic Games Store and other platforms. Maybe we should call this DRM-once-removed, rather than DRM-free.

Today, it's difficult to escape DRM in the gaming industry. Rising internet saturation provided the backbone for these verification systems, and players gradually accepted the terms because the trade-off was worth it. In a digital-first environment, it's much easier to click a "Buy" button than it is to haul your butt to the store. It's just that nowadays, "buy" doesn't mean what it used to.

The system is working, for now. Millions of players log into PS Now, Xbox Game Pass, Stadia, GeForce Now, Steam and the Epic Games Store every day, and their games are still there.

Well, most of their games.

$60 poorer and SOL.

Just today, Activision Blizzard unceremoniously pulled all of its titles from GeForce Now, including Call of Duty: Modern Warfare, Overwatch and World of Warcraft. Players are clearly displeased with the move, though most of the ire has been directed at Activision, rather than NVIDIA. Under NVIDIA's DRM-adjacent rules, anyone who downloaded an Activision Blizzard game before the removal should still own it, though there's no guarantee they'll have a PC capable of running it. After all, GeForce Now is a streaming service designed to make large, high-density games playable on any device. The people seeing the most benefit from GeForce Now specifically don't own a gaming rig. Anyone in this category who bought, say, Modern Warfare on NVIDIA's streaming service has suddenly found themselves $60 poorer and SOL, regardless of whether the game shows up in their personal library.

The conversation about the restrictive power of digital storefronts and DRM is on the rise again, though it's unlikely to result in industry-wide change. These discussions pop up when DRM features end up breaking a game or when a new store tries to take on Steam, but the fervor of the early 2000s has dissipated. Players rely on DRM in ways they never have before. As long as Valve, Microsoft, Sony, Epic, Google, NVIDIA and other platform holders keep their promises and manage to stay afloat, players won't have a reason to rebel against DRM in the same way again.

In other words, just give it time.