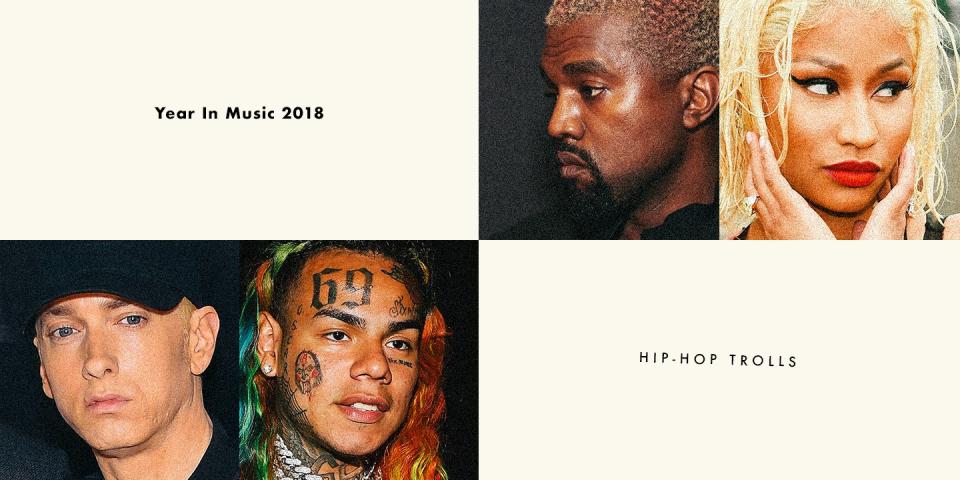

How 2018 Marked a New Era of Trolling in Hip-Hop

Amid an array of legal troubles, including an indictment on federal racketeering and firearms charges last month, Brooklyn rapper 6ix9ine became one of the music industry’s biggest success stories this year: He scored his first Top 5 hit, hundreds of millions of streams, collaborations with Nicki Minaj and Kanye West. Key to his rise was his dark mastery of garnering attention online.

Trolling is such a lifestyle for 6ix9ine that he has a routine. Watch him on camera enough times and a pattern emerges. First, a videographer presses record. Second, 6ix9ine announces his location. Next comes the taunt. “I got 15 burgers here, giving back to [the] community, ’cause you know these other Chicago rappers don’t give back,” he crowed on Instagram after walking out of a Windy City diner in June. The clips conclude with cash hitting the ground, ascending into the air, or being sorted. 6ix9ine’s rainbow plaits are a red herring; variety isn’t his signature.

Anyone who’s ever watched a Smack DVD, browsed WorldStarHipHop, or scrolled through Vine knows how hackneyed 6ix9ine’s flexing is. In the past, his antics likely would have sunken to the depths of the content ocean only to be occasionally salvaged for a meme or joke. But because he’s so reviled, his willingness to relentlessly finesse that hate—to troll—gives him a constant edge.

6ix9ine feeds almost exclusively on his notoriety, and it has been his strategy since his arrival. Before he was goading rappers, he was uploading noxious videos of underaged sex acts, actions that led him to plead guilty to using a child in a sexual performance in 2015. Since then, as his records have charted, he’s celebrated his continued visibility as if it were a goal in itself. He’s far from the first rapper with a Billboard obsession, but he might be the first rapper to have no other motivation. 6ix9ine’s persona is essentially a Vine loop of DJ Khaled saying “They don’t want you to win,” but with rainbow emojis.

And he wasn’t the only rap star to bank on agitation above all else throughout 2018. From Kanye’s “free thinking” to Nicki Minaj’s Queen Radio to king troll Eminem’s gaslighting of hip-hop writ large, trolling is becoming the go-to strategy for getting noticed. In pursuit of a constant, captive audience, rappers are tweaking their personas and their music to keep the curtain drawn indefinitely. This shift feels like both an adaptation to the streaming era and an indictment of it.

Trolling is a rap tradition. In the late ’90s, Eminem mocked white Americans’ contempt for rap by making the most puerile music he could think of—“Hi kids, do you like violence?”—and went on to become the biggest rapper in history. 50 Cent’s debut single “How to Rob” pestered New York media into overreacting; everyone who responded gave 50 far more legitimacy than the song could have alone. Soulja Boy countered Ice-T’s grizzled grandstanding (“Soulja Boy... single handedly killed hip-hop”) with insolent web humor (“You were born before the internet was created. How the fuck did you even find me?”). Peevishly smirking into his webcam, Soulja spoke as if he were being beamed in from a dimension in which Ice-T didn’t exist.

What’s shared in all these cases is a commitment to exploiting the gap between what is normal (competition, audacity, humor) and what is tolerated (bullying, derision, disruption). This is what trolls do: find cracks in standards and conventions and wedge them wider. For rappers, trolling is a natural extension of the skills needed in battle (wit, cunning, showmanship) and in the often crowded music marketplace (style, personality, narrative). Thus, on-air, on screen, on wax, and now online, rappers have always found canny ways to bend norms to their advantage—for the lulz, for the clout, and for the bag.

But where past trolling might have petered out as the next album took priority or a beef became unprofitable, today’s trolling is a lifestyle. Bhad Bhabie, for instance, is a troll by design. The viral “Dr. Phil” appearance that introduced her to the world is the horizon of her artistic ideas. All she’s expected to do is maintain the bewildered gaze that originally made her famous. Her music exists to be gawked at and despised, a dynamic that plays out in bizarre perpetuity as she then gawks at the gawkers by reacting to the reaction videos filmed in response to her music. It’s a joyless, monetized loop: She jeers, she’s mocked, she jeers again. It’s like she’s signed a 360-deal with infamy, the coziest Faustian bargain metadata can buy.

Younger rappers aren’t the only trolls. Kanye West has spent the year glibly serving the most half-baked ideas of his career. Convinced that provocation is a hallmark of creativity, he’s settled into a pattern of vexing spitballing that he calls “free thinking.” His thoughts largely consist of nonsensical riffs on design, freedom, and dead billionaires. At best, he sounds like he’s freestyling a TED Talk; at worst, he sounds like he’s freestyling a worldview. Either way, the spotlight never leaves him, and Kanye seems to be emboldened by that fixation. In the past few months he’s served as creative director for Pornhub’s award show, performed on “SNL,” visited the White House to rant about the MAGA hat, and railed against Drake and Travis Scott on Twitter. By any metric other than attention, these ventures have been pointless and unsuccessful. Kanye appears to have neither advanced his goals nor had any goals to begin with. His “SNL” performance was supposed to coincide with the release of his next album—but that album wasn’t even complete. He still got the headlines though.

The music that has emerged from Kanye’s morass has been just as circular. June’s ye and Kids See Ghosts essentially detailed his anguish and hope as he’s fallen from grace since becoming a right wing reactionary. Neither record grapples with his direct role in orchestrating that decline. In late October, when he abruptly “distanced” himself from politics after a year of provocation, there was no clear rhyme or reason why he had embraced them in the first place.

Scholar Whitney Phillips, an authority on web trolls, has described trolls as agents of “cultural digestion,” meaning they gnaw on culture and reproduce it in a corrupted form. Her research examines how those corrupted forms retain traces of the original “meal.” In this sense, Kanye’s trolling is a product of both his own predilections and the inherent asymmetry of the attention economy. There’s never been a time when Kanye’s Twitter presence was ignored, and this year he realized that even a lack of new or polished music wouldn't change that. As other celebrities confronted Kanye about his antics and were slowly folded into the spectacle, it became clear who held the reins. On Twitter, trolls always eat free.

AFP_19Y3Y2

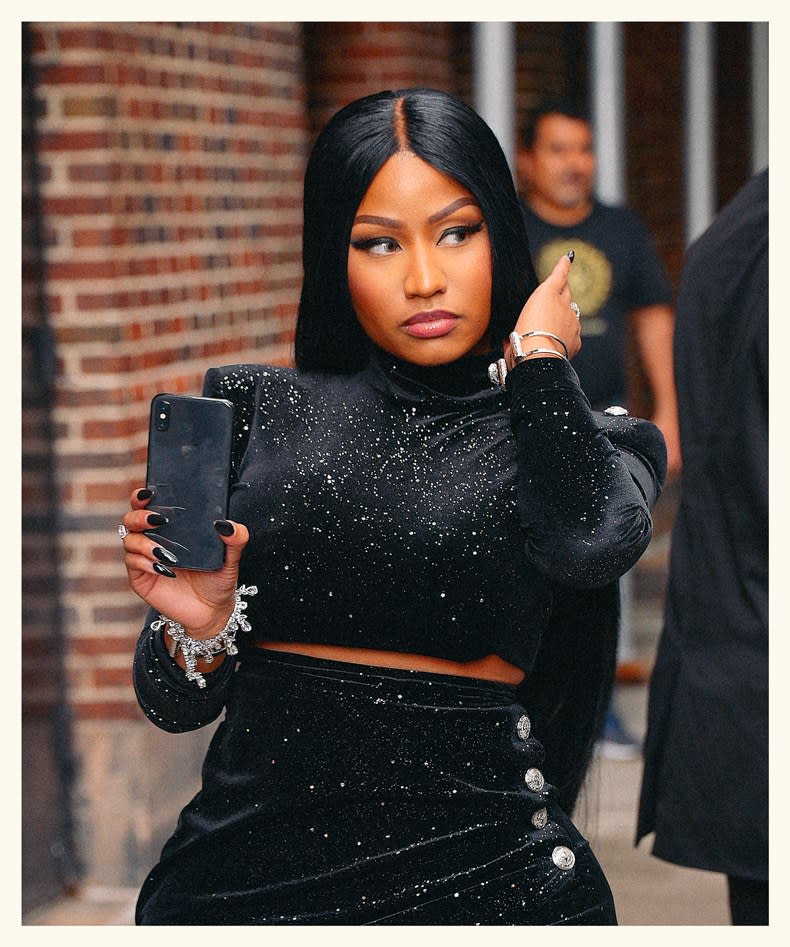

Radio is another space that's conducive to trolling, and Nicki Minaj’s Apple Music program Queen Radio has embraced that power wholeheartedly. In theory, the show exists to highlight the more relaxed and playful side of Nicki that’s obscured in her music and online presence. To that effect, she brings other musicians onto the show and asks them about their lives and upcoming releases, and she takes calls from her fans, the Barbz. At other times, Queen Radio is just a vehicle for Nicki to cannily launch pile-ons from her easy chair. Channeling the New York-based morning radio show “The Breakfast Club” and doling out awards like “cocksucker of the day,” or “dick rider of the year” (which, full disclosure, was exclusively awarded to Pitchfork), she riles up the Barbz with industry chatter and theatrical irritation then sits back as they descend on the “winners” with memes, jokes, and harassment. She’s essentially turned trolling into an industrial process. Or, more specifically, she’s taken the trolling that’s native to commercial radio and set up her own storefront—Queen Radio is boutique trolling.

And it works. Queen Radio clips and talking points hit the web quickly, prompting a flurry of reactions, disputes, sharing, and analysis that Nicki nibbles on in subsequent episodes. If standard trolling means shitposting into the void, Queen Radio is like the nitrogen cycle: Every little bit of energy is repurposed. The show is a shining example of what music journalist David Turner has identified as the “music as service” effect. “As the industry has monetized fan dynamics,” he writes, “moving toward participation as product, the perceived value of music has changed: it’s less about the artist, or even the artist's relationship to their fans, than ‘engagement’ itself.” Queen Radio is a greenhouse of engagement, well-insulated and temperature-controlled. All controversy is good; the best controversy is sustainable.

775077405RK017_Celebrity_Si

No rap artist has recently benefited more from bottling his own gas than Eminem. As his powers have dramatically dwindled, he’s made a cottage industry of his own flexing. Without a monoculture to rail against, he raps in uninspired knots, gracelessly working trending topics into his songs—Trump, the election, The State of Rap—to pantomime currency and edge. His recent music has the excitement of a birthday clown improvising balloon art.

Though his albums still top the charts, he’s responded to critics with outsized ire. “Fall,” his omnidirectional volley of insults, and the centerpiece of his 2018 album Kamikaze, received a tepid response from his targets, many of whom didn’t even tweet in response. The targets who did respond came out on top. Joe Budden’s podcast, for instance, was rewarded with one of its most streamed episodes. Similarly, Machine Gun Kelly, a proud member of the Eminem diaspora, hit back with a breezy reply that became a Top 20 hit. Eminem retaliated with the fiery “Killshot,” but he seemed to miss that the scope was aimed at his own foot. The same attention economy that inflated his bland jabs made a spectacle of his ineptitude. A few weeks after the dust settled, he took out an ad that celebrated his record sales by quoting all the publications that panned him. It was essentially an elaborate version of Nicki’s “awards”—and it was just as unfunny.

It’s easy to conclude that older rappers are aping the do-it-for-the-clout abandon of their younger counterparts. For Nicki and Kanye in particular, two artists that have previously expressed pride in the elder status, there’s certainly something youthful about their recent embrace of trolling. But considering how other figures in their age bracket, like Lord Jamar of Brand Nubian, Ebro of Hot 97, and RiFF RAFF, constantly float across YouTube trolling just as hard, the impulse transcends age. (Also, among their peers, Bhad Bhabie and 6ix9ine are anomalies. Outside of obligatory flexing and jet setting, the online lives of other young rappers mostly seem to be dedicated to playing “Fortnite,” sliding into DMs, and goofing off in the studio.)

The common denominator among rap’s trolls is airtight branding. Bhad Bhabie’s practiced sass, Nicki’s queendom, and Kanye’s Genius™ aren’t just personas or poises; they’re skinsuits, full integration of the public and the private. Trolls practice total devotion to the art. The mechanics of streaming reward consistency above all, and the smash-and-grab visibility afforded by trolling makes it easier to capture attention indefinitely. For normal folks, that kind of sustained attention is unthinkable—think about how often you ignore those “while you’re here…” messages attached to viral content—but for celebs, those moments happen every day, making trolling a cheap way to harvest that engagement.

Is all this trolling sustainable? It’s hard to say. The average meme rapper lifespan suggests not: Rich Chigga and 22 Savage, for instance, have already moved on to more fulfilling ventures as Rich Brian and FunnyMike. They seem much happier. Similarly, joke rapper Ugly God has recently teased a more mellow direction. Full integration of public and private life is draining; the skinsuit is tight. More importantly, meme makers and trolls reside on different ends of cultural flows. Creating memes is productive. Trolling is consumptive and reactionary; it’s designed to capture or redirect attention. And that’s its staying power. As long as there’s attention to reap, it’s hard to imagine rappers ever putting down the sickle.

If rappers ever do start easing up on the trolling, it will likely be a product of part-time trolls having all the fun. Vince Staples, for instance, began the year with a facetious GoFundMe campaign soliciting money for his retirement from music. It ended up being a promotional stunt for his caustic single “Get the Fuck Off My Dick.” I think of that snarky marketing every time I hear the song—and only then. Vince’s reputation isn’t affected.

The trolling of noise rapper JPEGMAFIA, a self-described “left wing Hades,” is also tactical. The antics on his timeline—chatter about video games, acidic political jokes, anime references—are clearly extensions of his ideas on his superb album Veteran, as well as his personality. But they don’t define him. His music is morose and contemplative just as often as it’s goading. Of course, there’s no way to know how Vince and JPEG would navigate social media if they had larger (or smaller) audiences, but for now at least, there’s always an out—for us and for them.

Ultimately, this year in trolling feels like an opportunity to think about the long-term effects of music being valued by how it circulates. It’s increasingly clear that, like radio and video in the past, streaming can be no less vulnerable to guile and craftiness. As Phillips observed as she studied trolls on various websites and forums, “platforms have a profound effect on how communities form and what community members are able to accomplish while online.” Trolls’ ability to streak across timelines and monopolize time is worth remembering as streaming services and social media companies consolidate power. This year we deemed them trolls. Next year we might be calling them influencers.