2002 rewatch: M. Night Shyamalan's Signs saw dark skies in dark times

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Every week, Entertainment Weekly is looking back at the biggest movies of the summer of 2002. As audiences struggled to understand the new post-9/11 world order, Hollywood found itself in a moment of transition, with upcoming stars and soon-to-be-forever franchises playing alongside startling new visions and fading remnants of the old normal. Join us for a rewatch of the first true summer of Hollywood's strange new millennium. Last week: Austin Powers' final horny hurrah.This week: Leah Greenblatt and Joshua Rothkopf sift through Signs. Next week: Vin Diesel goes XXX.

LEAH: Okay Josh, do you have random little water glasses set up all over the house, and a baseball bat you can reach from your laptop? Then you are ready to talk about Signs. It actually feels sort of poetic that we're celebrating this 20th anniversary right on top of the release of Jordan Peele's Nope, another alien-invasion thriller with auteur style and unanswered questions to spare.

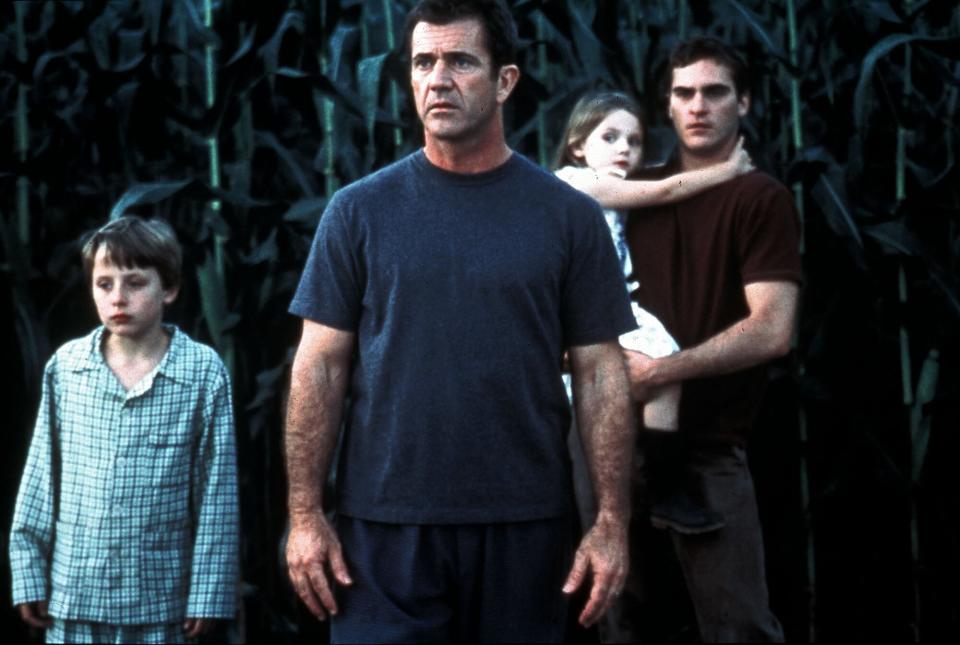

Which is not to say they're on the same page, or even quite the same planet, artistically. Signs is really pretty traditional in its setup and execution — I would even say deliberately old-fashioned, according to the whiplash-twist gospel of writer-director M. Night Shyamalan. Even the frantic, clattery orchestra of the opening theme, by nine-times-Oscar nominated composer James Newton Howard (The Fugitive, I Am Legend), makes the movie sound like it's headed for some kind of epic space adventure, or at least the kind of place Indiana Jones might need to bring his bullwhip. Instead it's just Mel Gibson in a corn field, staring at crop circles.

Mary Evans/Ronald Grant/Everett Collection

Gibson is an Episcopal priest named Graham Hess, newly widowed and also recently consciously uncoupled from his job, which means he spends a lot of the film reminding the townsfolk not to call him Reverend anymore. Those two losses, it turns out, are directly related: When his wife died in a terrible accident that the story reveals in teasing bits and pieces, so did his belief in a merciful God. Now he's raising two small children, Bo (Abigail Breslin) and Morgan (Rory Culkin) with the help of his younger brother Merrill, a washed-up minor league baseball player. (Joaquin Phoenix reportedly replaced Mark Ruffalo in the role after he had to drop out for brain surgery.)

Graham is not alright, but he's okay, until those circles show up in the fields behind the Hess's rural Pennsylvania home. He'd like to believe it's a dumb prank, just troublemakers from the next farm over. But the kids sense something else, and soon it's all over the news. It's also hiding out in those fields, as well as in his neighbor's pantry, and I have to say, I was not expecting the extraterrestrial visitors to look so… Weekly World News? I mean they're not Bat Boy, but they're almost drive-in-movie classic: slithery, gray-green, creeping in the bushes like hairless Yetis. We even get tinfoil hats! This is real Rod Serling stuff. But Josh, you tell me, were you a Shyama-man at the time? And how does all it hold up for you in 2022?

JOSHUA: My Shyama-love burned hot and brief: He'll always have The Sixth Sense, a deep film about the pain we unwittingly cause others. But as someone constitutionally unable to take superheroes seriously, I thought Unbreakable was ridiculous. Signs clarified Shyamalan further, as a defender of crazy flights of fancy (dead people! comic books! aliens!), and so he became progressively less interesting to me. So much strident insisting on things we can't see, so much somberness.

Your Nope comparison is spot-on, and it's revealing to compare those two films, just to see how Hollywood has evolved. Peele, whose screenwriting is only getting better, has made a UFO film in order to examine ideas of alien otherness on the ground as well as in the cool-blue night sky; Nope starts with a sci-fi premise only to crack it open and turn it into a metaphor for taming the natural world (and the unnatural one). Some characters are good at this, while others are just pretenders.

Shyamalan, on the other hand, just wants to go for the boo! of the jump scares. His movie is basically a reification of 1950s-style American toughness: us versus them, fighting against invaders. (Also, it's a sad thing when the only character of color is a drunk driver played by the director himself. That wouldn't happen now.)

At the time, it was impossible for me not to receive Signs as a big honking post-9/11 movie: Why do they hate us, Dad? Honestly, it still plays that way for me 20 years later, with scene after scene of characters watching city skylines on TV, waiting for the end of the world. Graham's shaken faith makes his family susceptible, and that final shot, the collar restored, reaffirms that he's living through some kind of holy war. In the era of Bush II, this made dark sense. I don't think Shyamalan has a political bone in his body, but horror movies take on the anxieties of their day. Even at the film's release, I called it "terrorized genuflecting."

I'm curious, Leah, did the movie put you back in that traumatized moment? Or does its distance make it feel more like a freestanding artifact?

LEAH: When Signs came out in theaters, I was not yet the Qualified Movie-Person Professional you see before you, so I think my main takeaway was basically, "Well, that was silly." But I'm with you 1000% on the general Shyamalan drop-off after The Sixth Sense, which I walked into cluelessly as a college student and was truly dazzled by. (Interestingly, I remember hating The Blair Witch Project, which came out that same year: good gimmick, bad acting, not scary.) I haven't revisited Sense in a long time, but at least back then, the human element of the story — besides, of course, that wild dime-drop twist — felt so threaded with melancholy and regret and a kind of emotional subtlety that Shyamalan's storytelling seemed to shed as he went along.

There is also the question of viewing Gibson through 2022 eyes, though I think he's totally solid here as the unsettled reverend. I actually Googled to see whether M. Night is religious while we were writing this, and it turns out he's not particularly — though he was raised in a Hindu home, and attended Catholic school as a kid. So it's interesting that Graham's conversion to godless nihilism and back again made the movie feel so much like one of those Left Behind morality plays: "See, nonbelievers? It's not that the Lord doesn't love you; He's just waiting to prove it to you via a terrifying and possibly humanity-ending War of the Worlds long game."

Walt Disney Co./Courtesy Everett Collection

I wonder if that general tone was influenced at all by Gibson, who is famously a devout Roman Catholic, or if in fact that's why he signed on. I'm not bringing this up to disparage anyone's personal faith, which I think is a private and beautiful thing. But it does give the movie an aura of magical thinking that doesn't exactly stand up to scrutiny. What about all the good people who didn't instinctively know that these scampering, malevolent E.T.s hate water, and thus failed to leave topped-off glassware scattered strategically in every room? Sorry suckers, you should have had your own Breslin!

Then again, all if not most Shyamalan movies tend to require some act of faith; that's how we buy James McAvoy's 23 personalities (a movie I totally enjoyed, by the way) or a beach that ages you like one of those time-lapse flower videos. I love what you said about entertainment taking on the anxiety of the times, and I wonder how differently a film like this might have landed pre-9/11, though its 2001 production window surely either preceded or straddled the actual event. Signs made over $400 million on release, so the answer in 2002 was clearly: not too shabby. Today though, it definitely feels like an artifact of the era, almost Americana kitsch. (As a side note, I enjoy that Shyamalan always has to have his Stan Lee moment when it comes to cameos, though you make a good point; surely he could have done himself better than playing a mom-killing saddie with like, four lines.)

Aside from the fact that this movie gave us a bonus Culkin and tiny, precocious Abigail pre-Little Miss Sunshine — Signs was her big-screen debut — what do you think of Joaquin? He was a couple years out from his career-defining villainy in Gladiator, and playing a very different role here, both aggressive and innocent; it's almost like a more caffeinated, less murder-y version of his turn in To Die For. Or does it even make sense to dig too much into the acting on this one?

JOSHUA: You're right: Faith is Shyamalan's organizing principle, movie after movie, but it was never weaponized as baldly as it is here. (Gibson knows something about that playbook: Signs is only two years away from his gory The Passion of the Christ.) I do find it mind-boggling that Shyamalan was apparently shooting around the time of 9/11 and production continued afterward. Perhaps the idea of reclaiming one's inner faith was a comfort at the time. It's the kind of script you can read almost anything into.

I actually love the acting in this one, in that I prefer a meek, nerdy and broken Gibson over a shouty one. He's even patient with Merritt Wever's pharmacy drama queen. There's not enough Cherry Jones here — she was born to play a cool-headed sheriff — but is there ever? It's a fail that she disappears after a while. A different kind of filmmaker, one less precious about his family-centric symbology, might have given her more of a role in repelling the invasion. That feels like money left on the table.

When I look at these kids, I only feel sad: I know they're supposed to be the children of a clergyman (and grieving), but have you ever seen a boy in so many tidy little button-downs? Breslin's Bo is spunkier in a studied Drew Barrymore mold, but Culkin's Morgan — and Haley Joel Osment in The Sixth Sense, come to think of it — are Shyamalan's type: soft-spoken, intuitive, a little boring. They don't feel like real kids, just surrogates for the filmmaker. In a film like Signs, they make the whole thing feel retrograde. Even Phoenix gets to find his higher purpose (is it the military? or "swinging away"?). Signs is the best movie of 1951.

And still, it comes from a place of confidence, before Shyamalan's steep decline. He wasn't that guy with the twist endings yet, not to my memory. He was just a gifted Spielberg disciple making a scarier, shallower Close Encounters. I hope that Peele is studying his career closely.

Read past 2002 rewatches:

2002 rewatch: All didn't glitter for Austin Powers in Goldmember

2002 rewatch: Road to Perdition brought prestige to blockbuster season. But was it any good?

Mr. Deeds launched Adam Sandler's biggest decade, for better or worse

How The Bourne Identity reinvented action for a new millennium

Insomnia was a flawed but promising daylight noir from pre-Batman Christopher Nolan

Star Wars: Episode 2—Attack of the Clones is still fascinating and confusing