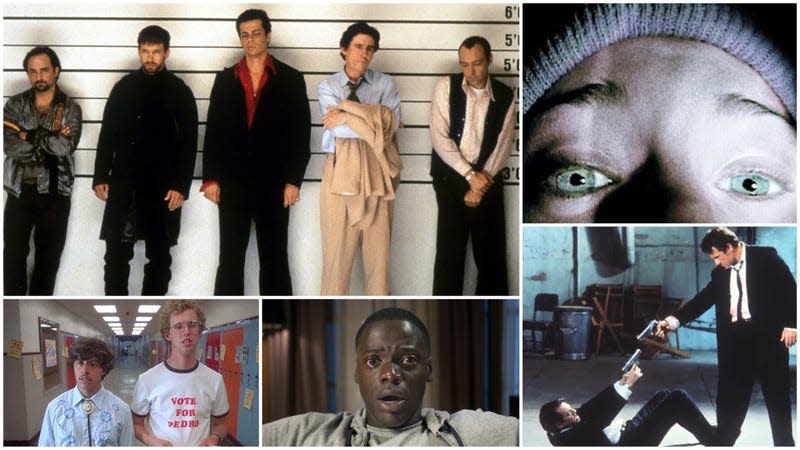

The 20 most unforgettable Sundance films ever

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

What began in 1978 as the Utah/United States Film Festival to help promote American independent cinema and boost film production in the Beehive State didn’t officially become the Sundance Film Festival until Robert Redford’s Sundance Institute officially took it over in 1985. Since then, Sundance has become one of the most influential film festivals on the planet. The festival has been introducing us to great films and great filmmakers for decades; almost two generations’ worth of our favorite films have sprung from the snow-covered but fertile ground of Park City. Here’s a chronological look at the 20 most transformative films to come out of Sundance, from 1984’s Blood Simple to 2017’s Get Out.

Blood Simple (1984)

Blood Simple helped launch the Oscar-winning careers of the Coen Brothers, who wrote, directed, and edited this film, which won the Grand Jury prize at Sundance in 1985. This gritty, slow-burn neo noir centers on Texas bartender Ray (John Getz), who gets caught in the middle of a murder plot when his boss discovers that Ray is having an affair with his wife (Frances McDormand). The Coens’ plate-spinning tension propels Blood Simple’s considerable twists and turns, helping the movie connect with both festival audiences and critics. It’s still considered one of the Coens’ greatest films. [Phil Pirello]

Sex, Lies, And Videotape (1989)

Before reality TV or social media, 26-year-old Steven Soderbergh made his feature debut with Sex, Lies, And Videotape, a movie about the fascinating notion of camera confessionals, and their unintended consequences—lessons every generation since has learned firsthand. A breakthrough movie for Andie MacDowell, and one that helped define James Spader’s onscreen persona as a vaguely unsettling type, it was just the first of many instances of Soderbergh being ahead of his time (watch 2011’s Contagion for an uncanny prediction of our current pandemic). Fueling the ’90s indie boom that also included films from directors like Kevin Smith, Quentin Tarantino, and Doug Liman, Soderbergh subsequently maintained a career that continues to vacillate between the bizarre (Schizopolis) and the big (the Ocean’s and Magic Mike franchises). Soderbergh would also go on to mainstream more independent cinematic styles with trademarks like mixed-media cinematography and audio overlaps over picture edits. [Luke Y. Thompson]

Heathers (1989)

This pitch-black comedy written by Daniel Waters and directed by Michael Lehmann is a scathing commentary on high school cliques, teen suicide and peer pressure. Winona Ryder plays Veronica Sawyer, a student who tries to fit in with a popular group of girls, all named “Heather.” But at the same time she’s attracted to the misanthropic outsider played by Christian Slater, who wants to blow up the school to bring about social change. Ryder was already a blossoming star after her roles in Lucas and Beetlejuice, but Heathers made her and Slater Gen X icons. The film debuted at the Sundance Film Festival in January 1989 and was released to the public in March of the same year. Although Heathers bombed at the box office as New World Pictures went bankrupt, the edgy coming-of-age tale won an Independent Spirit Award for Best First Feature and developed a devoted cult following on home video as the ridiculously quotable movie cemented itself in pop culture. Heathers spawned an off-Broadway musical and a TV series reboot that was too mean for today’s easily offended viewers, but, get crucial, the original is still so… “very.” [Robert B. DeSalvo]

Reservoir Dogs (1992)

Reservoir Dogs put Quentin Tarantino on the map, and Sundance helped pave the road to glory for both the blood-soaked crime saga and its bold and brash director. The first screening, though, was an utter disaster: the wrong lens was used to project the film, the house lights went up at one point, and the power went out at another point. A second screening generated serious buzz about the film and Tarantino’s potential as a filmmaker. There were walkouts at both screenings, though the ear scene pretty much guaranteed that would happen. Reservoir Dogs won exactly zero awards at Sundance, a fact that gnaws at Tarantino to this day. Nevertheless, he was thankful at the time for being invited to participate in the Sundance Film Lab, and the one-two awareness punch from Sundance and Cannes resulted in Miramax acquiring Reservoir Dogs, which cost all of $1.5 million to produce. Even though Harvey Weinstein wanted to cut the infamous torture scene, Miramax and Tarantino forged a partnership that resulted in several pretty great films. [Ian Spelling]

El Mariachi (1992)

A mariachi and a hitman, both carrying guitar cases filled with very different items, simultaneously arrive in a Mexican border town, and all hell breaks loose. That’s the basic plot of Robert Rodriguez’s action-packed, funny, suspenseful, sexy, and brilliantly shot El Mariachi, which cost just $7,000 to make. Rodriguez—who was 23 at the time—hoped to sell the finished product to the Latin American direct-to-video market, but was rejected time and again. Only then did he start to think bigger. The film miraculously found its way to Sundance in 1993, where it won the Audience Award and earned a pickup from Columbia Pictures. It grossed $2 million in the U.S. and established Rodriguez—who wrote, produced, directed, shot, and edited the movie—as a filmmaker with rare skills. El Mariachi also got dreamers dreaming; if this Rodriguez guy could hit the big time with a $7,000 movie, maybe they could, too. Of course, few others possessed Rodriguez’s raw talent—then or now. [Ian Spelling]

Four Weddings And A Funeral (1994)

Mike Newell’s Four Weddings And A Funeral launched the 1994 edition of the Sundance Film Festival. The British director was no stranger to Park City, as his Irish family movie Into The West premiered at Sundance just a year earlier. Andie MacDowell was already riding high on the success of Groundhog Day, but Hugh Grant and Rowan Atkinson enjoyed massive boosts from Four Weddings And A Funeral. Grant leapt from dependable supporting actor to leading man and Lord of the Romantic Comedy both in the U.K. and in Hollywood. Similarly, American audiences got their first real taste of funnyman Atkinson, who at the time was still best known for the very British television shows Mr. Bean and Blackadder. Four Weddings opened the door for Atkinson to make several internationally popular Bean and Johnny English features, and for him to steal scenes in The Lion King, Rat Race, and Love, Actually. [Ian Spelling]

Clerks (1994)

No matter your thoughts on the two sequels (and the short-lived animated series) spawned by Kevin Smith’s 1994 feature debut, there’s still a certain aura about the original Clerks for both longtime Smith fans and those who think he’s never done anything better. Yes, there’s still an undeniable charm in the DIY indie spirit of the whole piece, from the black-and-white photography to the single-location banter between Dante (Brian O’Halloran) and Randal (Jeff Anderson) as they go about a single day at a New Jersey convenience store. Yes, Jay (Jason Mewes) and Silent Bob (Smith himself) are fun to watch in their very first outing. Yes, the soundtrack is still packed with grungy ’90s throwback cuts. But the power of Clerks, and the reason it has endured for nearly three decades, extends beyond these moments of appeal and into something deeper. In risking it all to make his feature debut about two guys who feel stuck in their lives, Smith unearthed something primal and true in Gen-X viewers and beyond, and the result is one of the most insightful movies about slackers ever made. [Matthew Jackson]

Hoop Dreams (1994)

Born of an assignment for a half-hour PBS special, Hoop Dreams, which premiered at Sundance in 1994, put filmmaker Steve James on the map, winning the festival’s Audience Award for Best Documentary. Shot over the course of five years, the movie focuses on the lofty NBA aspirations of two Black teenagers from disadvantaged communities, William Gates and Arthur Agee, who are recruited to play basketball at a private, predominantly white prep school. Released on the heels of MTV’s groundbreaking The Real World (but, it must be noted, the film was started before that project), Hoop Dreams landed as a lived-in, deeply moving piece of cinematic portraiture, exploring the complexities of race, socioeconomic opportunity, and education in American society. Despite its length (2 hours and 50 minutes, whittled down from over 250 hours of footage), the movie was both a critical smash and an arthouse hit. Its Sundance-minted $11.8 million theatrical gross indisputably altered both the entertainment industry’s perception about the commercial viability of documentaries, as well as the public’s relationship to nonfiction films, paving the way for the future box office success of everything from Bowling For Columbine and Fahrenheit 9/11 to March Of The Penguins and Walt Disney Studios’ Disneynature label. [Brent Simon]

The Usual Suspects (1995)

“Who is Keyser Soze?” is the apparent central question in The Usual Suspects, the second feature from Bryan Singer, who went on to greater commercial success with the X-Men franchise. Working from a fiendishly clever script by Christopher McQuarrie—who himself went on to become Tom Cruise’s favorite writer/director—Singer’s film starts out with an explosion in which 27 die. A police detective questions one Verbal Kint who, with several of the dead men, had previously been rounded up for questioning about a seemingly unrelated heist. As he interrogates Kint, the latter’s story of what really went down gets more and more convoluted and baroque, with constant references to the sinister Soze, who is presented as pure evil and impossible to identify. The real central question, however, is just how much an audience can trust what’s on the screen. No film since Kurosawa’s 1950 classic Rashomon had so thoroughly exploited the old film noir concept of the “unreliable narrator.” Besides providing us with that one great catch phrase, The Usual Suspects reminded us not to take all cinema confessions at face value. [Andy Klein]

The Blair Witch Project (1999)

Utilizing one of the earliest online viral marketing campaigns before such things even had a name, Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez’s ultra-low budget The Blair Witch Project managed to convince some viewers it was real. One of the most profitable films ever, Blair Witch went on to gross $250 million worldwide, and make found-footage into a vibrant subgenre. It also arguably helped spawn the modern insistence on going into movies spoiler-free: those who saw it first believing it might be authentic tended to enjoy it more than mainstream audiences catching it months later, after multiple reviews praised its power of suggestion, happily “spoiling” the fact that you never actually see anything especially scary onscreen. The sequel went in such a different direction that the series never became a franchise juggernaut, but eight years later, Paranormal Activity would pick up that found footage ball and run with it to the finish line, and beyond. [Luke Y. Thompson]

American Psycho (2000)

What makes a cult classic? Well, American Psycho is a prime example. It’s a film that was released to no fanfare, mild excitement and tepid box office but gained in notoriety as the years went by. A devoted loud few implored others to check it out. Its reputation built on repeat viewings on VHS, streaming and in repertory theaters. It even inspired a short-lived Broadway musical. And all of this started at Sundance in January 2000. Directed by Mary Harron, who co-wrote the screenplay with Guinevere Turner and based on the novel by Bret Easton Ellis, American Psycho is a pointed and sharp satire of American consumerism and the “greed is good” culture that had its heyday in the 1980s. Its anti-hero Patrick Bateman (played by Christian Bale, who took it on after Leonardo DiCaprio passed) has become the poster boy for a certain type of scruples-free corporate go-getter, ensuring that this film’s legacy lives on. [Murtada Elfadl]

Memento (2000)

Following, Christopher Nolan’s first feature, was shot on weekends over the course of a year, but its ingenious plot and visual style drew enough attention for him to finance Memento, which was an instant sensation. The film, which made its U.S. premiere at the 2001 Sundance Film Festival, features a structure that is utterly novel: the hero suffers from a form of amnesia that allows him no more than 15 minutes of continuous experience before essentially wiping out that 15 minutes and resetting to an earlier state. To see the action as he experiences it, Nolan gives us a series of scenes presented in reverse order that are intercut with shorter scenes that progress forward. The result is one of the greatest puzzle films ever made. It’s never dull, but it takes multiple viewings to figure out exactly what the hell is going on. One would never have predicted the trajectory of Nolan’s subsequent career: After revitalizing a worn-out franchise in Batman Begins, he began making hugely expensive, successful blockbusters, only a few of which—Inception and Interstellar, in particular—dealt with the sort of challenging issues that made Memento such an indelible experience. [Andy Klein]

Garden State (2004)

In the years since its release, Garden State’s reputation has unfairly lost a bit of its luster, overwhelmed by the omnipresence of its lilting alt-rock soundtrack (cue The Shins’ “New Slang) and assailed by revisionist cultural critics mostly for what it’s decidedly not. In its tackling and assessment of depression, youthful ambivalence and delayed-onset adulthood, however, Scrubs star Zach Braff’s feature writing and directorial debut still feels on-target—and in many ways prescient, offering up a compelling snapshot of the same type of debilitating emotional dislocation that fuels so much of the daily churn of social media. Following its premiere at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival, Garden State was purchased for $5 million, double its production budget. It went on to gross over $35 million in its theatrical run, and that aforementioned soundtrack won a Grammy Award. Even if Braff (whose latest effort, A Good Person, starring Florence Pugh, releases in March) hasn’t quite blossomed into a bonafide auteur, his debut film helped plant a commercial flag for the soul-searching work of aspiring young writer-directors, and remains a smart, engaging look at quarter-life confusion. (Brent Simon)

Napoleon Dynamite (2004)

We have Sundance to thank for Napoleon Dynamite, and by extension for tater tots, quesadillas, “Vote for Pedro” shirts, ligers, side ponytails, the “Canned Heat” dance, and saying “Your mom goes to college.” One of the most ubiquitous cult hits of the 2000s, one that’s spawned endless amounts of merch, pop culture references, and Halloween costumes, Napoleon Dynamite is a true Sundance success story. In 2002, Jared Hess made a short film called Peluca for a college assignment. The film was accepted into the 2003 Sundance Film Festival where it caught the eyes of producers. Peluca was then expanded to the feature length Napoleon Dynamite, which arrived the following year to Sundance without distribution. It was snatched up by Fox Searchlight and given a very limited release, but the quirky masterpiece quickly found an audience to become one of the most quoted films of all time. Now if you’ll excuse me, “TINA. YOU FAT LARD! Come get some dinner!” [Matthew Huff]

Saw (2004)

The gory thriller that caused pundits to cry “torture porn!” and launched the career of James Wan, as well as the most convoluted franchise narrative in horror history, Saw actually borrows its central hook from the original Mad Max: in a time crunch, will a shackled victim attempt to saw through his chain, or, more efficiently, his own leg? It’s a “would you rather” dilemma so visceral that the Watchmen comics had already cribbed it previously. Using the aesthetics of industrial music videos, and a score by Charlie Clouser, director Wan and co-creator Leigh Whannell constructed a twisty, mildly preposterous narrative that, unlike its more soap opera-esque sequels, remains genuinely creepy. Keeping its mastermind and his key minion mostly in the shadows, the film focuses on figuring out clues and using self-mutilation to stay alive. Cast solely on the strength of his voice, Tobin Bell became a complicated horror icon so popular that even death couldn’t stop his return in infinite follow-up flashbacks that continue to this day. [Luke Y. Thompson]

Little Miss Sunshine (2006)

Little Miss Sunshine, about a dysfunctional but endearing family of misfits, helped widen the already considerable spotlight on the festival when it premiered at Sundance in January 2006. The film proved to be an instant hit with the Sundance crowd, as enthusiastic word of mouth reached back to Hollywood, leading to one of the biggest acquisitions in the festival’s history at that point. Fox Searchlight picked up the film for $10 million, and it went on to gross $101 million worldwide and score four Academy Award nominations. In addition to Michael Arndt’s win for Best Original Screenplay, co-star Alan Arkin also won for Best Supporting Actor. Moreover, Sunshine would raise the bar on indie darlings-turned-mainstream-crossovers and it would inspire studio execs to spend the next few years looking for projects that could replicate its success. Some movies came close (think Juno), but most only reinforced how unique and special Little Miss Sunshine really was. [Phil Pirello]

Winter’s Bone (2010)

Before Winter’s Bone premiered at Sundance in January 2010, no one knew who Jennifer Lawrence was. She had made appearances in TV shows like Medium and Cold Case and had a supporting role on The Bill Engvall Show. But it was her performance as Ree Dolly, a teenager in rural Missouri trying to protect her siblings and make ends meet, that made her an immediate star. The film’s awards journey started at Sundance where it won the grand jury prize. At the Oscars, Lawrence received a best actress nomination to go along with the film’s three other nods (best picture, best adapted screenplay and best supporting actor for John Hawkes). A year later, Lawrence was cast in The Hunger Games and the rest is history. This marks perhaps the only time that a Sundance debut launched an actual bonafide movie star with box office chops. Director Debra Granik went on to introduce another searing young talent—Thomasin McKenzie—with her 2018 film, Leave No Trace. [Murtada Elfadl]

Fruitvale Station (2013)

The major careers that this small film launched are no less than Ryan Coogler and Michael B Jordan. Based on the true story of how the Bay Area police murdered Oscar Grant, a young Black man out with friends on New Year’s 2009, Fruitvale Station premiered at Sundance in January 2013. At the time, Octavia Spencer, fresh off her Oscar for 2011’s The Help, was the biggest name in the cast. Jordan was known for his critically acclaimed performances in The Wire and Friday Night Lights, but this marked Coogler’s film debut as a director. After it premiered, Fruitvale Station was immediately pegged as a Sundance breakout destined for the mainstream and awards season, like Little Miss Sunshine (2006), Precious (2010) and later, Coda (2021). Fruitvale Station didn’t quite reach those heights but its legacy remains potent because it launched these two careers, without whom we wouldn’t have Creed (2015), Black Panther (2018) or Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2021). [Murtada Elfadl]

Whiplash (2014)

While Whiplash is not Damien Chazelle’s directorial debut (that would be his black-and-white indie musical Guy And Madeline On A Park Bench), it certainly is the film that launched him to stardom, and Sundance is the festival that launched that film. As with many features from fledgling directors, Whiplash began as a short. The 18-minute film about a drummer and his abusive conductor premiered at Sundance, where it won a jury award and gathered enough attention to garner feature-length treatment. Chazelle’s full-length masterpiece returned the following year in the opening night slot, was quickly bought by Sony Pictures Classics, and was given a year-long awards campaign culminating in three Oscars, a Best Picture nomination, and Chazelle’s first Oscar nod for the screenplay. With 2016’s La La Land, Chazelle became the youngest Best Director Oscar winner, cementing himself as one of cinema’s finest young auteurs. [Matthew Huff]

Get Out (2017)

Jordan Peele’s transition from comedy great to rising horror auteur was always going to be something everyone watched closely, but even with tremendous hype in the lead-up to its debut, the world wasn’t quite ready for what Get Out had to offer. We expected something funny, smart, and well-crafted from one-half of the Peabody-winning Key & Peele duo, but what we got went beyond those adjectives and into another realm. Premiering with a midnight screening at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival, Get Out’s story of a young Black man (Daniel Kaluuya) finding more than he bargained for at the house of his white girlfriend’s parents delivered the scares, then went further, steeping every moment in multiple meanings until it emerged as one of the most psychologically and thematically satisfying horror films in recent memory. The horror world has never been the same since, and Peele has only gotten better and more ambitious. [Matthew Jackson]