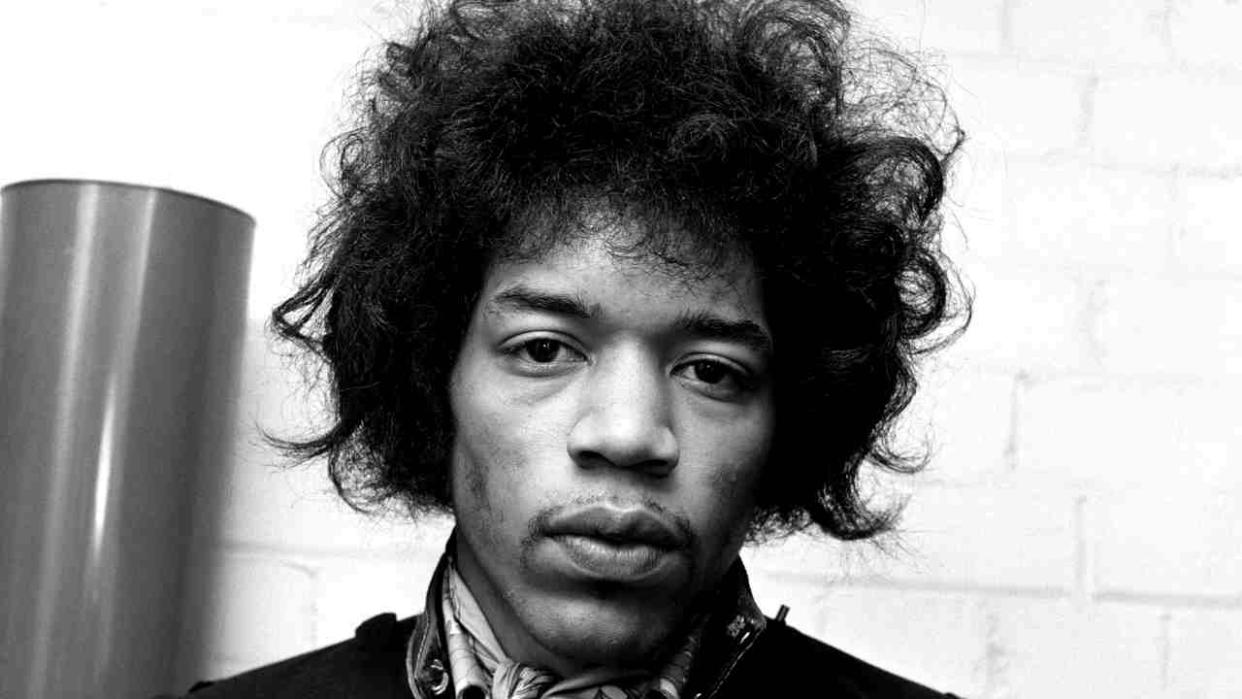

The 20 best Jimi Hendrix songs

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Jimi Hendrix’s recording career lasted just four years, but during that time he revolutionised the guitar and rock’n’roll itself. The songs he recorded with The Experience – and later, Band Of Gypsys – have long part of the DNA of rock music itself, while his incendiary performances on record and onstage have never been matched. But what’s the best Hendrix song of all time? We threw it open to a public vote – and here are the winners.

20. Star Spangled Banner

On the morning of August 18, 1969, Hendrix played Woodstock with his short-lived ensemble Gypsy Sun And Rainbows. Towards the end of his set, he dropped in a overdriven, distorted and generally fucked-up version of hallowed US national anthem The Star-Spangled Banner. Conservatives and patroits instantly claimed it was wholly inappropriate and offensive, and caused them to wretch into their own hands, while others believed it to be a noisy statement against the Vietnam War. So what’s the answer? Well, it’s said that by the time Hendrix took to the stage that morning, he’d been awake for three consecutive days. So the answer is anyone’s guess, really.

19. Hey Baby (New Rising Sun)

Hendrix chipped away at Hey Baby for more than two years – christening and retitling it at various intervals along the way – and you can hear the guitarist’s ever-changing moods in the shapeshifting song that finally appeared on his second posthumous set, 1971’s Rainbow Bridge. The intro underwhelms slightly with its dour, non-committal churn. But Hey Baby finds its groove with the reggae-ish chop that enters after the first minute, before Jimi finds his voice (“Is this microphone on?”) and the song joins the canon with the propulsive lift-off of the“Hey girl, I’d like to come along”refrain. That fourth album would have really been something…

18. If Six Was Nine

Later included on the Easy Rider soundtrack, this psychedelic blues was the 60s counterculture in excelsis, from Hendrix’s pot shots at “white collar conservatives flashing down the street” to the likely influence of LSD (“I didn’t find out until after we finished that he’d been taking acid,” confessed producer-manager Chas Chandler). A cameo from Graham Nash stomping his feet on the track bled into a free-form outro, with Hendrix tooting on a borrowed recorder. “So here’s Jimi freaking out,” engineer Eddie Kramer recalled, “and of course I stick a lot of echo on. And the guys are stomping away like mad. It sounds like galloping horses!”

The elaborate production was almost in vain, after Hendrix left the Axis: Bold As Love master tape in a taxi. Redding saved the day by supplying an early mix on an arse-rough open-reel tape, and the bassist also took credit for the outro: “When we all go into three separate time signatures, that’s basically an idea of mine, because we didn’t know what to do at that one point in the song.”

17. Manic Depression

After Chandler criticised Hendrix’s interview manner as “manic depressive”, the guitarist had his title, even if the lyric seemed more to do with thwarted love than mental health – “I wish I could caress and kiss, kiss…”. With Mitchell’s muscular jazz rolls high in the mix, Hendrix’s riff climbing upward through the verses, and his vocal flowing across the 3/4 metre, Manic Depression seemed to have no centre of gravity – and was all the better for it. That seasick vibe probably stopped its promotion to a single from Are You Experienced, but Hollywood Vampires’ 2015 cover was a reminder that the hardcore were listening.

16. Angel

Six months after his death, Hendrix lived again in March 1971, as Angel led out the first posthumous album, The Cry Of Love, and announced that the late guitarist’s catalogue would be a going concern. As you’d expect of Little Wing’s sister song (for a time the two tracks even shared a title), Angel was a peerless moment of glisten and shimmer, with a valedictory chorus that seemed purpose-made for the star’s passing (although Hendrix had actually written it about a dream that foresaw his mother’s death). With a chorus that punctured the mainstream consciousness, for many, it’s his greatest ballad.

15. Crosstown Traffic

Three tracks into Electric Ladyland, Hendrix dropped the album’s first jukebox moment and most accessible cut. For once including all three Experience members – plus Dave Mason on backing vocals – Crosstown Traffic’s rocket-heeled R&B would have thrilled under any circumstances, with Hendrix splicing chords and single-note runs within the same guitar part. But the pièce de résistance was Hendrix’s joyous doubling of the hook, tooting on a comb wrapped in cellophane for a kazoo effect. Electric Ladyland had more ambitious moments, but nothing so immediate.

14. Are You Experienced?

The Experience’s debut album might have opened up with Foxy Lady’s chart-tooled swagger, but the final straight had a bolder trick up its sleeve, with a title track that signposted the epic studio productions to come. Mitchell’s military drum tattoo was the anchor of a freeform sonic tapestry that bent to Hendrix’s will, sweeping up backwards guitars that were more raga than rock, a solo seemingly beamed in from another track, and a woozy call to arms that urged listener to ditch the denizens of their “measly little world”– far better, Jimi suggests, to “hold hands and watch the sunrise from the bottom of the sea”.

13. 1983... (A Merman I Should Turn to Be)

By spring 1968, Electric Ladyland had suffered its first casualty, with Chas Chandler quitting over Hendrix’s obsessive attention to detail and habit of inviting the flotsam of the New York club scene back to the studio. With the brakes off, 1983... (A Merman I Should Turn To Be) saw Hendrix dive deeper on a 13-minute psychedelic epict hat sprawls between the backwards flute of Traffic’s Chris Wood, seagull squawks created with microphone feedback and amphibious lyrics that spoke of escaping the “fighting nest” and “screaming pain” of dry land. It was hard to disagree with Kramer’s assessment that “when Chas left, we were off to the races”.

12. Foxy Lady

Few recorded sounds in ’67 held more anticipation than the shiver of vibrato and feedback that ignited Foxy Lady. The song, when it crashed in, caught the guitarist at his hardest, hookiest and most primal, the riff’s shrill payoff demanding attention every few seconds. But Hendrix rejected interpretations that the lyric was a brash ode to womanising, and it’s more likely the title referred to his times with on/off girlfriend Lithofayne Pridgon. “He used to call every pet we had Foxy,” Pridgon told The Guardian. “Or if I put on certain things, he’d say, ‘Wow, you look foxy in that.’”

11. Castles Made of Sand

Eddie Kramer saw this late addition to Axis: Bold As Love as “Jimi’s imagination run wild”. Certainly, that’s true of the production – the burbling backwards guitar still sounds revolutionary – but the lyric is perhaps his most grounded in reality, Hendrix tracking a disintegrating family unit that younger brother Leon claimed was their own: “That is the story of our life, about my mother and father arguing, in the first verse. I’m the little Indian boy who before he was ten played war games in the woods: that’s my verse. And then the last verse is about our mother. Jimi came home and said, ‘This is our family song’.”

10. Bold as Love

Axis: Bold As Love’s semi-title track was redolent of Little Wing in the opening measures, but the revelation came at 2:50, when Kramer unveiled the stereo phasing that he and tape operator George Chkiantz had used to treat the drums. “When Jimi first heard that,” Kramer recalled, “he fell off the couch, yelling at me: ‘Oh my god, this was in my dream!’” Rising to the occasion, for the outro Jimi played a soulful, album-best solo that climaxes with frantic tremolo picking and, according to Redding, was created on the fly: “The ending and the build-up was all spontaneous between the whole band.”

9. Red House

At first glance, Red House hardly squared with Hendrix’s iconoclast reputation. Three tracks into Are You Experienced, it set out its stall as a no-frills slow blues, following twelve-bar dogma at trudging pace, skirting plagiarism of Albert King’s Travelin’ To California. But at the two-minute mark – “That’s alright, I still got my guitar, look out now!”– Hendrix elevated the song with a solo of such unadorned beauty that it equalled anything in his bag of tricks. It was so good, noted John Lee Hooker, that it would make you “grab your mother and choke her.”

8. Voodoo Chile

It would never be as celebrated as its (almost) identically named offshoot, but amidst the rampant experimentation of Electric Ladyland, Voodoo Chile was a reminder that few could touch Hendrix on a route-one blues. Nodding hard to Muddy Waters’ Rollin’ Blues and Hoochie Coochie Man – with a stir of sci-fi to boot – the structure was secondary to the vibe, with Hendrix corralling Steve Winwood and Jack Casady at the Record Plant for a freeform 15-minute take that remains one of the quintessential wee-small-hours ’60s studio jams. “There were no chord sheets, no nothing,” recalled Winwood. “He just started playing.”

7. Machine Gun

Historically an opaque lyricist, Hendrix left no doubt of the inspiration behind the Band Of Gypsys high-water mark, dedicating it onstage at the mighty 1970 Fillmore East show to the soldiers in Vietnam (and those braving riots on home soil). Scuttling on muted strings and squalling over Buddy Miles’ rat-a-tat drumming, Machine Gun was the most visceral of protest songs, catching the dread of war. “It’s so atmospheric, it’s so moody, it’s so stoner-rock – even before stoner-rock – and virtuostic at the same time,” Metallica’s Kirk Hammett told Classic Rock. “He really brings you there, to the killing fields.”

6. The Wind Cries Mary

The gossamer lilt of the Experience’s third single, according to Hendrix’s then-girlfriend Kathy Etchingham (middle name Mary), was at odds with its volatile inspiration, the repentant guitarist writing it by way of apology after a blow-up over mashed potatoes: “He tastes them with a fork and says they’re all lumpy. That’s how the argument started.”

The January ’67 session at London’s De Lane Lea Studios moved fast, remembered Chandler (just 20 minutes to play through with Mitchell and Redding, plus overdubs), but you’d never guess it: while London shook with blues scales, Hendrix’s jazzy three-chord shift at the end of the chorus sounded impossibly sophisticated.

5. Hey Joe

Hendrix’s arrival in London in September 1966 sent shockwaves through the capital’s musical community. Like some left-handed guitar-playing James Bond, women wanted to be with him, and men – especially Eric Clapton – wanted to be him.

The culmination of this summer of madness was Hendrix’s debut single. Hey Joe was a murder ballad, previously recorded by US folkie Tim Rose. The story of a man who shoots his ‘cheatin’ ol’ lady’ and flees to Mexico was blunter than anything by supposed bad boys The Who or the Rolling Stones. But initially Hey Joe, with its gospel-style backing vocals, pottered along like a regular pop song. Then, around the 1:27 mark, Hendrix’s increasingly fervent vocals and stun-gun guitar took it somewhere new. The result was as exercise in menace and understatement; every slow-burn hard rock song of the late ’60s and beyond squeezed into three-and-a-half peerless minutes.

4. Purple Haze

With the Experience’s debut single Hey Joe, Hendrix had complained, “wasn’t us” (literally: it was a cover). Follow-up Purple Haze corrected that, with a brain-dump of Hendrix’s myriad interests, from sci-fi to sex, and possibly psychedelics (he variously explained the inspiration as a dream of walking on the sea bed, and the “daze” of chasing an unattainable woman).

That first draft, the guitarist reflected, had sprawled to “a thousand words… I had it all written out”, but Chandler, eyeing radio, helped prune Purple Haze back to a more palatable three minutes – without sacrificing a lick of what (arguably) nudges Voodoo Child as Jimi’s signature guitar moment. The opening two-note jolt (an unsettling tritone interval rightly nicknamed ‘the devil in music’) and three-chord verse might have been a basic canvas, but with his frighteningly adept lead – taken to the stars by revolutionary use of Roger Mayer’s Octavia pedal – Hendrix announced himself beyond question as the virtuoso and sonic adventurer to beat.

3. Voodoo Child (Slight Return)

The wah-wah guitar pedal was a relatively new invention when Hendrix used it to devastating effect on the unforgettable introduction of Voodoo Child (Slight Return), and while that intro is the song’s most memorable feature, Hendrix treats the entire composition as a vehicle for expression. He alternates between rhythm and lead playing at the blink of an eye, and both riffs and solos frequently pan from left to right to add to the swaying, hypnotic nature of the performance. His guitar parts are backed up by the solid, unwavering playing of bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell, who allow him the breathing space he needs to take the dynamics down and up.

Released in format somewhere between a single and an EP, Voodoo Child (Slight Return) was backed with Hey Joe and Hendrix’s immortal cover of Bob Dylan’s All Along The Watchtower – the song remains another reason for Hendrix’s reputation as a man for whom a guitar was not simply an instrument. As his devotees believe, his iconic Fender Strarocaster was a vehicle for the expression of his essential soul.

2. Little Wing

If the languid guitar flourish that opens Little Wing sounded like it was rolling impulsively off Hendrix’s fingers, the musical roots were, in truth, a little more tangled. In ’66, channelling the rhythm playing of one-time tour-mate Curtis Mayfield, the journeyman guitarist had thrown similar shapes on(My Girl) She’s A Fox, during a run with R&B duo The Icemen. That same year, after-hours loiterers on New York’s Greenwich Village circuit might have heard those glistening trills resurface as Hendrix tinkered with the guitar part, honing the piano-style voicings that were only possible because his long thumb was able to reach over the neck to fret the low bass notes.

Post-fame, the lyric came faster, in a flash of inspiration at Monterey, as Hendrix imagined the festival’s love-your-brother vibe personified into an“angel came down from heaven”(“I figured that I take everything around,” he reflected, “and put it maybe in the form of a girl”).

Even then, Little Wing could have turned out very differently. In an October 1967 session at Olympic, following on the heels of the hot-headed Wait Until Tomorrow, early passes were more rocking, but patently not the right treatment. Hendrix reconsidered, slowed the pace, and Little Wing became an ethereal masterpiece, decorated with a glockenspiel and a DIY Leslie speaker whose tremulous tone he compared to “jelly bread”. “The Leslie was a tiny, handmade thing,” said Eddie Kramer, ”with a little Meccano set to support it and a rubber band driving a motor.”

The production was perfect – but the track is defined by the cascading guitar work that later covers by Stevie Ray Vaughan and Eric Clapton valiantly chased but never quite caught. Of the Experience’s three original albums, Axis: Bold As Love might be home to Hendrix’s deeper cuts, but Little Wing remains a calling card.

1. All Along The Watchtower

It was, said Bob Dylan of All Along The Watchtower, “a small song of mine that nobody paid any attention to”. But at the end of ’67, Jimi Hendrix was repeatedly dropping the needle on this unloved corner of Dylan’s John Wesley Harding LP, hearing something deeper in than the rudimentary three-chord strum.

Hendrix was a Dylan fanatic, to the point where apocryphal tales told of him clearing the dancefloor of a New York club by insisting the DJ play Blowin’ In The Wind. But he was something more, too; the guitarist felt a deep kinship that meant he considered the two writers’ oeuvres entwined, …Watchtower being another of those Dylan compositions so on his wavelength that “I feel like I wrote them myself”.

Hendrix had been spotted around town with the John Wesley Harding vinyl under his arm, and had become fixated on the fourth track. “I remember Jimi said to me, ‘That’s the coolest song’,” Traffic’s Dave Mason told Guitar World.

By January 1968 – just a month after Dylan’s original had landed – Hendrix was ready to build his own Watchtower, albeit within the constraints of London’s Olympic Studios’ primitive four-track set-up.

He squeezed out Noel Redding, choosing to overdub the bass himself. “That pissed off Noel no end,” recalled engineer Eddie Kramer, “and off he would go to the pub.” Drummer Mitch Mitchell remained on the stool, and might have been seen to scratch his head as Hendrix taught him how to turn around the intro beat. Likewise, across the studio floor, a guesting Mason – no slouch on guitar himself – struggled with a 12-string rhythm part that Kramer noted “always buggers people’s minds up”.

The session crawled on, clocking upwards of 27 takes. At least a couple of those misfires might have been attributed to Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones, who fell through the door of Olympic, paralytically drunk, and commandeered the piano.

“Jimi could never say no to his mates, and Brian was so sweet,” groaned Kramer. “He came in and said ‘Oh, let me play’. It was take 21 and we could just hear ‘clang, clang, clang, clang’. It was all bloody horrible and out of time, and Jimi said ‘Uh, I don’t think so’. Brian was gone after two takes. He practically fell on the floor in the control room. Dear Brian…”

But the gathering reel of tape were also testament to an interpretation that was evolving at rapid pace, from a lighter and bass-free early take with Hendrix strumming acoustic, to the glowering, heavily layered studio collage of legend. That summer at New York’s Record Plant, Hendrix went down the rabbit hole again for Watchtower’s vocal and percussion, benefitting from the quantum leap of the studio’s 16-track technology. Perhaps he was never truly satisfied with All Along The Watchtower: “I think I hear it a little bit differently,” he kept saying, according to engineer Tony Bongiovi, as overdubs came and went.

But Hendrix came back out with a masterpiece. The original had hinted at impending apocalypse, with its imagery of growling wildcats, howling winds and sinister horsemen. Yet there is a limit to the foreboding that can be summoned with an acoustic and reedy harmonica. With his interpretation, Hendrix left no doubt of the intended mood. Opening with a staccato clang of guitar and drums, followed by string bends that evoked a car alarm, the sonic impression was of a world spinning off its axis into darkness, with a little of the same gathering storm of the Stones’ Gimme Shelter. Little wonder that decades later, when Tom Hanks’ character patrols the jungle hellscape of Vietnam in Forrest Gump, it’s Hendrix’s song that soundtracks the scene.

Hendrix admitted he couldn’t match Dylan for lyrics. “I could never write the kind of words he does,” he said. But nobody, then or now, could touch Jimi’s guitar playing. Supported by a production bed that takes in everything from looping to backwards tape effects, the solos that punctuate the song remain extraordinary, Hendrix slipping from wah-soaked flourishes, to haunted Hawaiian swoons, to the trilling single-note outro.

Kramer remembers Jimi using a Gibson Flying V, and studiously working out his path through the solo in advance. But more spontaneous was the way he grabbed for knives, beer bottles and, finally, a Zippo lighter for the slide work. “Well, there were a lot of devices that he used,” the engineer reflected in Total Guitar. “A Zippo was one of them, but he was known sometimes to use his rings.”

Released in September 1968 as the lead single from Electric Ladyland, All Along The Watchtower was not so much a cover as a song rewritten from the ground up. To hear it was to almost forget the existence of the original, which now seemed a mere blueprint by comparison. The song reached No.5 in the UK and No.20 in the US, making it Hendrix’s breakthrough success in his homeland. To date, it has been streamed on Spotify almost 400 million times – more than twice the total of the song in second place, Purple Haze.

As for Dylan, he was magnanimous, scarcely believing what had come from his raw materials. “It overwhelmed me, really. He had such talent, he could find things inside a song and vigorously develop them. He found things that other people wouldn’t think of finding in there. He probably improved upon it by the spaces he was using. I took licence from his version, actually, and continue to do it to this day.”