“When 18 and Life played back and I heard Scotti play the first three notes in the solo, I got chills. I called Jon Bon Jovi and said, 'Do you ever get chills listening to your own music?'”: Snake Sabo and Scotti Hill on Skid Row's massive debut album

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Atlantic Records released Skid Row’s self-titled debut on January 24, 1989, the New Jersey band had humble hopes for the album.

“What I remember was that we were really just praying that we could sell enough records to make another record, so that we could do this for a living,” recalls guitarist and co-founder Dave “Snake” Sabo.

35 years on, it seems that prayer was answered, and then some.

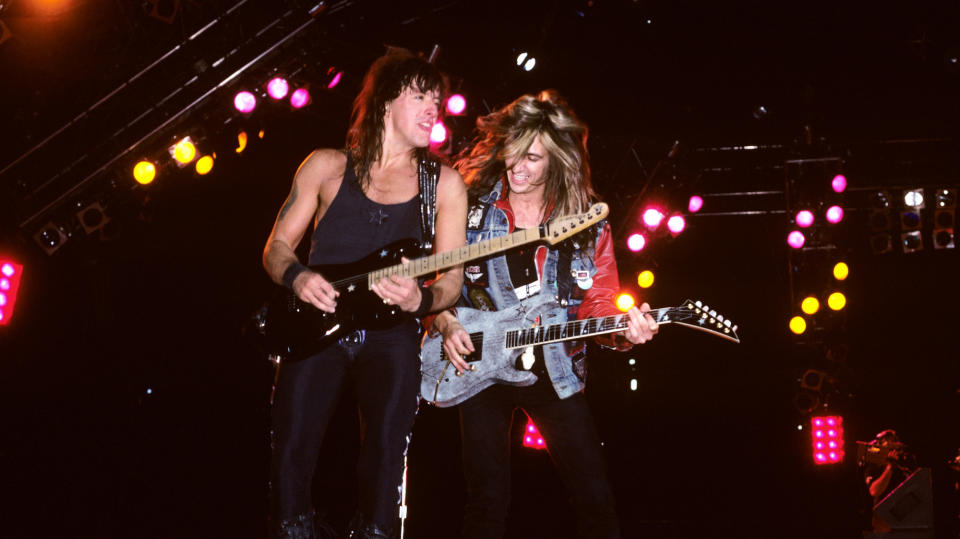

Fueled by Sabo and Scotti Hill’s heatseeking dual-guitar attack, three massive singles – Youth Gone Wild, 18 and Life, and the power ballad I Remember You – and incendiary live shows supporting the likes of Bon Jovi, Aerosmith, and Mötley Crüe, Skid Row was a multi-platinum, MTV- and radio-dominating smash.

The record established the band – Sabo, Hill, bassist and co-founder Rachel Bolan, drummer Rob Affuso, and multi-octave shrieker Sebastian Bach – as the most exciting and explosive new act on the scene, and is today considered an avowed hard-rock classic. “We were a hungry band,” Hill says of that era. “To put a Rocky spin on it, it was eye of the tiger.”

Skid Row laid the groundwork for even bigger things to come, including a chart-topping album with the even-heavier 1991 follow-up, Slave to the Grind, and globetrotting runs with everyone from Guns N’ Roses to Pantera.

Though there have been struggles along the way – a breakup in the mid ’90s, public spats with Bach, various lineup shifts – Skid Row, still anchored by Sabo, Hill, and Bolan, and also featuring drummer Rob Hammersmith and vocalist Erik Grönwall, are currently operating on a high once again, and gearing up for more live dates in support of their acclaimed 2022 effort, The Gang’s All Here. And there’s still more to come.

“We’re going to start working on new material at some point soon,” Sabo says. Assures Hill, “There's always shit in the works at soundcheck, so long as we're on tour, new music's happening.”

Until then, Sabo and Hill got together to jump on a Zoom call with Guitar World and take a look back at the record that started it all.

So it’s officially the 35th anniversary of Skid Row. Does it feel that long ago? Or is it like it was yesterday?

Dave “Snake” Sabo: “I don't know if it seems like yesterday, but I personally never thought that I would even make it to 35 years old, much less have a record that I made with my brothers 35 years ago.

“Thinking back to it is kind of like when you think back to a rerun coming on TV of I Love Lucy or something. You've seen it before, and then you remember, 'Wow – I know what happens next!' Of course, back then we didn't know what happens next. We were just so happy to be in a real studio with a real producer, far away from home.”

It was an old Playboy hotel in this weird resort area, with a couple of golf courses on it...

You tracked the album at Royal Recorders in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin.

Scotti Hill: “That’s right. And at that point, going to another state, aside from, you know, New York or Pennsylvania or maybe Connecticut, was kind of a big deal. So Wisconsin, it was like, 'Wow!'”

Sabo: “It was an old Playboy hotel in this weird resort area, with a couple of golf courses on it. Which, we've come to find out, was the reason we were really out there – so our managers could go golfing every day while we sweated and toiled in the studio! But it was actually really cool because they had a great studio there.

“Michael Wagener went out there to check it out, and he was like, 'This is perfect.' And it was also situated near Alpine Valley Music Theatre, and a lot of the artists that would play there during the summer would stay at the hotel. So it was an opportunity for us to meet these artists who were touring on a big scale and had had a great amount of success. It was very inspiring.”

Michael Wagener had a long resumé at that time, having worked with everyone from Dokken and Accept to Metallica, Mötley Crüe, and White Lion. How did he get involved in the project?

Hill: “We used to go to record stores and look at the backs of albums. And Snake – maybe you remember this? One day we went to the store and we're pulling records out of the rack and looking to see who the producer was. We pulled out a Stryper record [1985’s Soldiers Under Command] and it said, 'Produced by Michael Wagener'. And that’s how his name came into the conversation.”

Right from the get-go, you established yourselves as a great guitar tandem, with each player bringing a ton of personality and character to the music, and contributing equally to the rhythms and leads. How did you work together?

Sabo: “Well, I remember when Scotti first joined he said to us, 'I just wanna be in the band. I'll just play rhythm guitar.' And we kind of all looked at each other, like, 'You're crazy, dude! How could a guy as talented as you just play rhythm guitar?' And that's the truth. Because he’s amazing. And we've never had issues with ego as far as competing against one another. Of course, we attempt to outdo each other, but there’s just a tremendous amount of respect for one another and wanting to push each other to another level.

“It's not necessarily demonstrated verbally – it’s demonstrated through when you're jamming and you're doing pre-production, and all of a sudden you'll hear something that the other guy does and you go, 'Holy shit!' And, more importantly, it’s always in service of the bigger picture. It’s always about the song, not the solo. I went through periods where all I cared about was how fast I could play. And then Scotti joined the band and I see him doing these beautiful legato runs with this crazy vibrato…”

Hill: “…I believe the technical term is 'legato shit'. [laughs]

Sabo: [laughs] “Right. But it was really eye-opening. It's kind of like the universe goes, 'All right, dude, you’ve got a lot to learn. Here's someone that's going to show you something.'”

Hill: “Snake and I always worked together as a team, and we just bounced shit back and forth. A lot of what we did – and still do – is, when we're not one big train going down the middle, it’s more of a point-counterpoint thing. Snake actually pointed that out to me one day. He put on Last Child, by Aerosmith, and he said, 'Listen to what they're doing back and forth.' And we started throwing that kind of stuff into our playing.

“I also remember doing pre-production on that first record and having one of his cabinets over by me and vice versa, so we could hear what the other guy was doing. Because, I mean, you could go a 40-year career and not know what’s going on over on the other side of the mix, you know? [laughs]”

I remember hearing the song played back in the studio, and when it got to the solo and Scotti plays those first three notes, I got chills

Do you have a favorite guitar moment from the other guy on that first record?

Hill: “Sweet Little Sister. I love that solo of Snake’s. It's like, 'Wow! What was that?' It starts out with, like, a Chuck Berry riff and then rips through some fast notes at the end. It's traditional and aggressive and it flies right by. It's really cool.”

Sabo: “I have two with Scotti. One is actually both of us, and that’s Youth Gone Wild. That song became an anthem for us, and it was our story. It summarized the band. And the solos we play are really an extension not only of ourselves as individuals, but the song and the story as well. But my real favorite solo of Scotti's, and this might be obvious, is 18 and Life, because it's just absolutely iconic. 35 years later, it's the most played solo of Skid Row’s of by other guitar players online. It's so hummable and so melodic.

“I remember hearing the song played back in the studio, and when it got to the solo and Scotti plays those first three notes, I got chills. I remember I called up Jon Bon Jovi and said, 'Hey dude, can I ask you a stupid question?' I go, 'Do you ever get chills listening to your own music?' Because I felt guilty. [laughs] I felt like, 'You don't deserve this.'”

What gear were you using in the studio?

Hill: “My main guitars were my blue Jackson and my red Spector Les Paul Jr.-style model with the Floyd Rose. There's also a Strat on there for a couple of little spots. But pretty much it was just those two guitars for me.

“As far as amps, we used a combination of a bunch of stuff. Mainly, this ADA [Hill holds up an A/DA MP-1 preamp]. Not one like this – this one, exactly. I bought it from Michael Wagener when he closed his studio. It’s the one that Vito [Bratta] played through, the one that Nuno [Bettencourt] played through. Then we had some Marshalls that we brought in – we brought everything we owned – and we also used some of Michael's stuff, like a McIntosh power amp.”

Sabo: “Michael also had a Groove Tubes power amp that we used for some lower end. And we used a modified Marshall for some of the lower end as well. I also had my Ibanez Tube Screamer and my MXR six-band EQ. And I used a Roland JC-120 Jazz Chorus for 18 and Life and things like that.”

Snake, what were your main guitars?

Sabo: “I had a black ‘71 Les Paul Custom with a Floyd Rose on it that I used quite a bit, and a pink Kramer with a humbucker and two single coils. I also had a single-cutaway Les Paul Jr. that I played on a couple of things – the solo for Here I Am and some rhythm stuff in other songs. For acoustics I played Ovation six- and 12-strings, and of course I had my Kramer 'Snake' guitar.”

Kramer reissued that guitar as the Snake Sabo Baretta a few years back. Do you and Kramer have anything else in the works?

Sabo: “We do. We’re going to do two new guitars, with different configurations and different fretboards and fret wires, different radiuses, things of that nature. For a while we were moving forward really quick, and then the band started touring like crazy. But I talked to the folks over there over the Christmas holiday and we’re going to pick it back up and get it going for this year.”

Scotti, I’ve noticed from following you on Instagram that you’ve been getting into the gear game as well, by building your own guitar pedals.

Hill: “I have. It actually started with a kit that I got during COVID, I think it was one of those StewMac kits. I did a bunch of those and then I was like, 'Eh, it's kind of paint-by-numbers.' So I started looking up schematics.

“I figured out the Fuzz Face, which is a very basic circuit – it's got maybe 12 components inside of it, and it's very customizable. So I built some Fuzz Face pedals, and then I built a Rangemaster and a Distortion+. I got one of those MXR Distortion+ pedals in ‘79 – I still have the receipt in the box [laughs], I was like, 'I'm gonna see if I can make one just like that'. And it sounds pretty close.

Everybody around us was going, 'Look what's happening to you guys!' And we were like, 'What’s happening?'

“Now, I’ve made 10 of them. I'm also building a buffer for my live rig, because I have a lot of cable running out to my tuner. So it's just something I started doing that has turned into a hobby. And I detail the inside of the enclosures and make them look cool and more like pieces of art. But I'm not reinventing anything, I'm just copying schematics.”

What have you been doing with the pedals?

Hill: “Well, I started by giving 'em away. And then people were contacting me online and saying, 'I wanna buy one'. I'm like, 'All right, if you wanna gimme money, I'll take your money. Sure!' [laughs] But it takes a lot of time to make them. I'm doing everything by myself – sourcing the parts, drilling the enclosures, making the circuit boards. It’s fun, but it’s time consuming.”

Getting back to the record, do you remember the first time you really felt like things were taking off for the band?

Hill: “I mean, we went on tour with Bon Jovi three days before the album came out, so we were moving so quickly and covering so much ground that it was really hard to see. Everybody around us was going, 'Look what's happening to you guys!' And we were like, 'What’s happening?'

“You’re kind of aware, because you see how the crowds are reacting as the tour goes on. But we were in our own little road bubble. It almost seemed like it was happening to somebody else, in a way. Like you’re watching it from the outside.”

Sabo: “One thing I do remember was playing a club in Fort Lauderdale called Summers on the Beach – this was, like, February of ’89 – and seeing the Youth Gone Wild video on the Top 15 countdown or whatever on some show.

“That was an incredible experience, because we were in the club getting ready to do soundcheck, and there happened to be a TV hanging from the ceiling, and… there we were. It was like, 'Wait a second. How can that be? If I'm right here in the middle of Summers on the Beach, how can I also be on the TV?' [laughs] It was very surreal, but in the best way possible.

“So like Scotti said, to an outsider, it would probably seem like we were in a tornado, but we were very confined. We had 12 people on a 40-foot bus, standing and sleeping on top of each other. And we still didn't have a pot to piss in. We weren't making hardly anything for the shows, and we were living in one-bedroom apartments. My kitchen still had a slope where, if you put a marble on the table it rolled off the other side.”

Hill: “I remember right before we went on tour, I had a red Honda that broke down on Route 36… and I just left it there. [laughs] I didn't get another car until we came home, 16 months later.”

Sabo: “But we couldn't have cared less about any of that. We were playing music for a living.”

Obviously, Skid Row have gone through some ups and downs over the ensuing decades. But when you look back on those early days during the first album cycle, what sticks out to you the most?

Sabo: “I think for me, personally, the greatest part of it was standing on the edge of the stage, basking in the sound of that audience appreciating what you just did and saying, 'You know what? We did this together. For better or worse, at the end of the show, at the end of the day, we all did it together'. That was always the most gratifying feeling.”

Hill: “We were five guys, but we were a band. We were a gang. As time crept on, there were some things that were difficult. But those early days were really exciting, innocent times.”

Sabo: “That was part of the magic of that whole first run. You know, Scotti used the word innocent, and innocence is always lost. But when it's in its purest form it’s so special, and you wish you could keep it forever. Of course, life just doesn't work that way. But when it works like it did for us, it's really something to behold.

“So, no matter how many records we’ve sold or people we’ve played for, we always were very humbled by our success and never took it for granted or felt that it was owed to us in any way. Even to this day, Rachel, Scotti, and myself are always like, 'Holy crap! Can you believe this?'”

Skid Row are set to tour North America in February and March. For tickets and more info, visit the band's website.