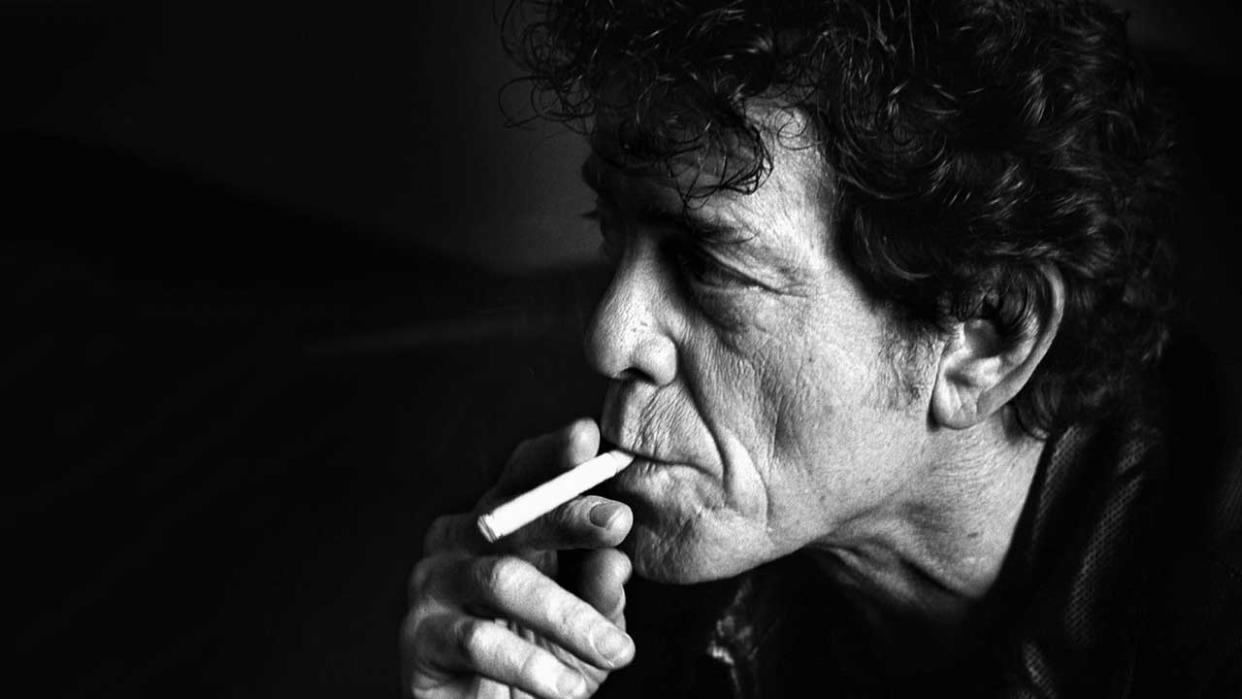

12 examples of the songwriting genius of Lou Reed that aren't Perfect Day or Walk On The Wild Side

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

With a poet's eye for detail and a knack for storytelling, Lou Reed's best songs crafted narratives that depicted the underbelly of society, its misfits and outcasts. With his Brill Building background, Reed married a natural tunesmith's grasp of melody to lyrics that tackled themes of addiction, alienation, love and urban decay.

Reed's occasional forays into the upper echelons of the pop chart might have kept the wolf from the door ("Without it, who knows, maybe I’d be digging a ditch somewhere," he said of Walk In The Wild Side), but there's plenty of evidence for his genius elsewhere. Here are just 12 examples.

I’m Waiting For The Man (The Velvet Underground & Nico, 1967)

Reed’s vérité description of copping $26 of Harlem heroin, set agains a two- chord riff and an edgy drumbeat that impels the listener to the edge like a clucking junkie. For those who heard it, the 70s started here.

Sister Ray (The Velvet Underground - White Light/White Heat, 1968)

Imagine Booker T. And The M.G.’s forced to play avant-garde jazz in the most tumultuous sub-basement of Hell for 17 and a half minutes, as Lou intones a subterranean tale of sailors, drag queens, smack dealers and death. How was this not a hit?

Sweet Jane (The Velvet Underground - Loaded, 1970)

This Dead Sea Scroll of glam confirmed Lou’s position as New York City’s poet laureate. An irresistible four-chord riff, so obvious in its perfection that you wonder how The Kinks missed it, is allied to a lyric so street-smart it’s virtually picking your pocket.

Satellite Of Love (Transformer, 1972)

The gorgeous follow-up to Walk On The Wild Side stiffed as inexplicably as its predecessor hit. Originally recorded but overlooked for the Velvets’ Loaded, its candy-coated space-age vernacular and cuckold angst was produced by Bowie for Transformer.

Sad Song (Berlin, 1973)

The exemplification of Bob Ezrin’s rarely-understated production genius, Sad Song marks the conclusion of Reed’s magnum opus. Poorly reviewed by a music press lacking in discernment and vision, Berlin’s beautiful tragedy of divided souls in a divided city endures as his defining solo masterpiece.

Kill Your Sons (Sally Can’t Dance, 1974)

Personal, vitriolic and damning, Kill Your Sons documents Reed’s confinement in Creedmore state psychiatric hospital, where he was given electroconvulsive therapy as a teenager at the behest of his parents to ‘cure’ him of bisexual tendencies. A stinging indictment.

Kicks (Coney Island Baby, 1975)

Coke-fuelled paranoia is realised in this noir vignette, at odds with Coney Island Baby’s saccharine mood. Against a loosely focused bed of cocktail-party chat, Lou’s pro/antagonist reveals himself as an American psycho who gets his “adrenaline flowing” by murdering casual pick-ups. Genuinely disturbing, rap-presaging genius.

Street Hassle (Street Hassle, 1978)

If one composition encapsulates Reed’s art, it’s this. An 11-minute piece based on a cello earworm and divided into three parts, it allies Gotham vernacular to situations reminiscent of Hubert Selby Jr.’s Last Exit To Brooklyn (hooker, drugs, death).

The Bells (The Bells, 1979)

Working with Ornette Coleman sideman Don Cherry inspired Lou to raise his game on an otherwise unremarkable album. Self-produced to otherworldly effect, The Bells builds from climax through crescendo to its payoff, as his vocal coda chills.

The Blue Mask (The Blue Mask, 1982)

If one strand endured throughout Lou’s career (from Venus In Furs to Lulu), it was his fascination with S&M, described in unflinching detail. The Blue Mask finds a newly sober Reed and co-guitarist Robert Quine scaling summits of feedback unheard since White Light/White Heat.

Strawman (New York, 1989)

No longer speaking for a disenfranchised few, politically- motivated Lou voices the concerns of a disgruntled constituency sick of inequality running rife beneath the ‘Statue of Bigotry’. Reed and Mike Rathke’s guitars ooze honeyed mercury.

Vanishing Act (The Raven, 2003)

Captured in contemplative mood (exposed by Friedrich Paravicini’s minimalist piano arrangement), Lou cogitates on the welcoming oblivion of disappearing into anonymity, before fading into a richly merciless Jane Scarpantoni string arrangement. Soul-crushingly beautiful.