On the 110th Anniversary of Titanic's Sinking, Revisit Chilling Tales of Life and Death from the PEOPLE Archives

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

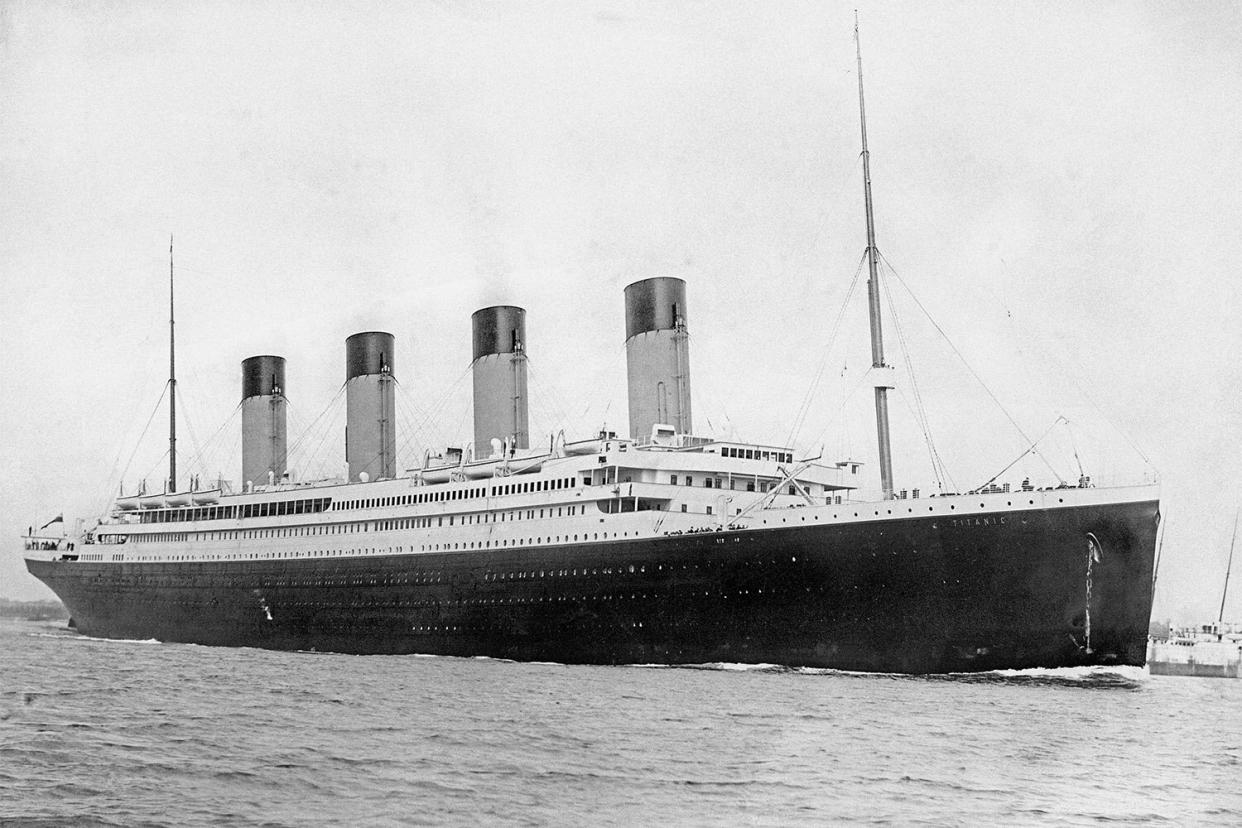

Getty Digitally restored vintage maritime history photo of the RMS Titanic departing Southampton, England

Editor's Note: It's been 110 years since an estimated 1,500 people died in the sinking of the Titanic on April 15, 1912. PEOPLE is taking a look back at the tragedy by republishing "Sunken Dreams: Tales of Life and Death from a Night to Remember," which originally appeared in the March 16, 1998 issue.

The great ship sank with a slight gulp, witnesses say. It was early morning, April 15, 1912, 700 miles east of Halifax, Canada.

RMS Titanic, on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, had sideswiped an iceberg 2 1/2 hours earlier, popping rivets and buckling the hull's iron plates deep below the waterline. Furiously, the sea rushed in, flooding one watertight compartment after another of the ship's supposedly unsinkable hull until the bow was submerged and the tail stood upright against the black sky. At 2:20 the ship slid below the surface completely.

So much for the physics. But what captured the public's attention was that night's human tragedy. Titanic set sail carrying some 2,200 people — millionaires, immigrants, 13 honeymoon couples, and an eight-man band that played to the bitter end — and lifeboats for just over half of them. In the end 712 were rescued; the rest drowned or froze in the water.

"It was the biggest ship in history, filled with celebrities of that time," says James Cameron, director of the blockbuster film Titanic, which has become the first film to gross more than $1 billion worldwide, been nominated for a record-tying 14 Oscars and propelled actors Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet into superstardom's rarefied realm. "It would be like if you took a jumbo jet filled with half the stars in Hollywood and crashed it into the Washington Monument."

Yet Titanic's sinking was not instantaneous, and in her dying moments fateful choices were made. A look at her real-life victims includes both tales of valor and too-human frailty.

Getty Molly Brown

MOLLY BROWN — Not even an iceberg could slow down this dynamo

Mrs. J.J. Brown's 1912 tour of the Old World had been a smashing success. She bought antiquities in Egypt, hobnobbed with John Jacob Astor, one of the world's richest men, and visited her daughter, Catherine Ellen, at a Paris finishing school. Even after news of a sick relative cut short her stay, Brown was lucky enough, or so she thought, to book a ticket home on the finest ship afloat: Titanic.

The steamer went down, but not the "Unsinkable" — as she came to be known — Molly Brown. Loaded into lifeboat No. 6 (capacity: 65) with 24 women and two men, Brown, in a black-velvet, two-piece suit, argued fiercely with Quartermaster Robert Hichens, who refused to return to the wreck site for fear survivors in the water would swamp the boat. To fight the bitter cold, Brown taught the other women to row and shared her sable coat.

And when Hichens dismissed a flare fired by an approaching ship as a "shooting star," Brown threatened to throw him overboard (although not, as in the 1964 movie musical bearing her name, while waving a pistol). Once in command, she ordered the women to row to safety.

RELATED: The Cast of Titanic: Where Are They Now?

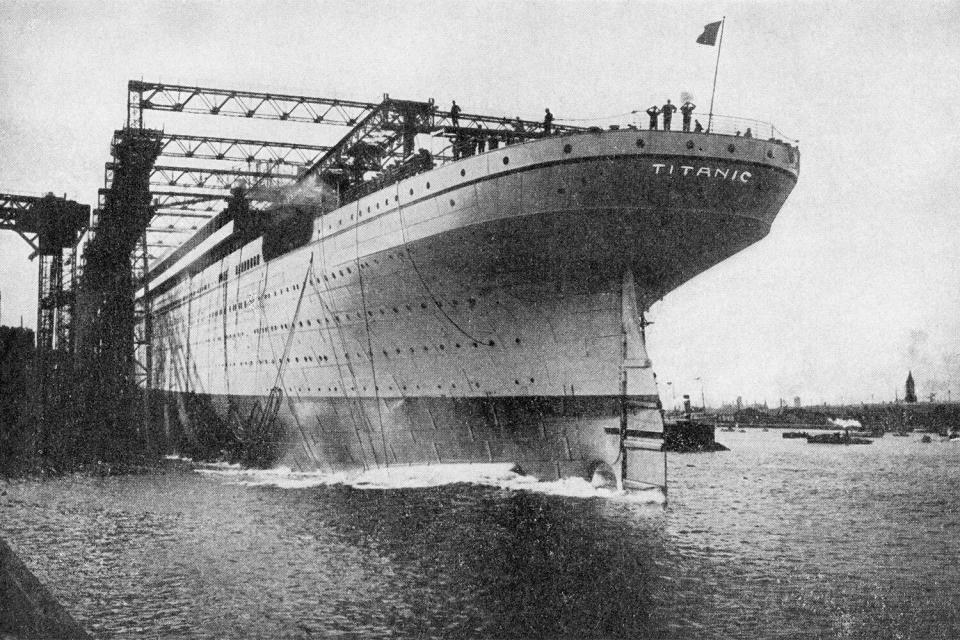

Design Pics Inc/Shutterstock The launching of the Titanic of the White Star Line at the Harland and Wolff shipyards in Belfast on May 31, 1911.

Brown had proved her mettle yet again. Born Margaret Tobin in Hannibal, Mo., in 1867, she left the poverty of her hometown behind and moved when she was 18 to the boomtown of Leadville, Colo., to find "work and a rich husband," says her great-granddaughter Muffet Brown, a Los Gatos, Calif., graphic designer.

She met prospector James Brown, 13 years her senior, at a church picnic and married him in 1886 — seven years before he struck gold at the Little Jonny Mine and began building his $5 million fortune.

Molly, though, couldn't abide being confined to their Denver mansion. She traveled, often with her son Lawrence, to Europe and mastered several languages before separating from James in 1909. After the ship sank (with 13 pairs of her shoes and a $325,000 necklace), Brown raised funds for poor survivors and fought for women's suffrage. But most of all, Brown, who died after a stroke in 1932, enjoyed her fame as the pluckiest of Edwardians. "Simple Brown luck," she said after the wreck. "We're unsinkable."

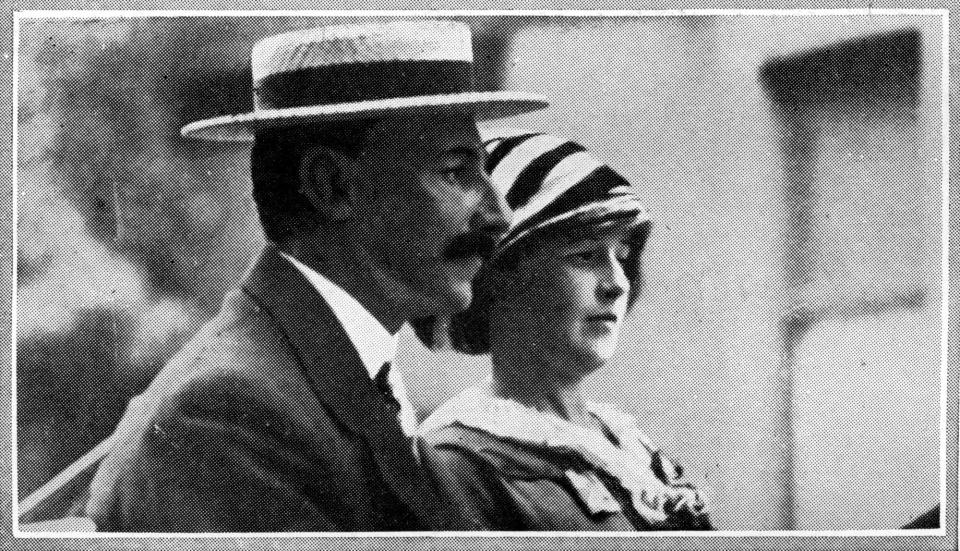

Universal Images Group/Getty John Jacob Astor and Madeleine Force

MADELEINE AND JOHN JACOB ASTOR — An American millionaire and his wife bade farewell forever

On a vessel flush with tycoons, New Yorker John Jacob Astor IV stood out as the richest. He boarded at Cherbourg with an entourage that included his wife, Madeleine, a manservant, a maid, a nurse and his Airedale, Kitty. First-class staterooms like theirs — richly paneled suites with working fireplaces and separate quarters for servants — cost as much as $4,000 for the voyage, equivalent to a staggering $50,000 today.

But there was more to Astor than the $87 million fortune he made through real estate and his family's fur-trading empire. After graduating from Harvard, he patented such inventions as a turbine engine, a bicycle brake, and a "vibratory disintegrator" used to produce gas from peat moss. He wrote a science-fiction novel about life on Saturn and Jupiter and financed his own army battalion during the Spanish-American War. His first marriage, to Ava Willing of Philadelphia, lasted 10 years and produced two children.

But his second marriage, to Madeleine Force in 1911, caused a scandal. She was 18 at the time, and he was 46. To escape wagging tongues, the couple took an extended honeymoon in Europe and Egypt (where they joined his friend Molly Brown). By the time they boarded Titanic, Madeleine was five months pregnant. "They wanted the baby born in America," says historian Don Lynch.

RELATED: The Titanic: Looking Back at the Ship's Tragic History

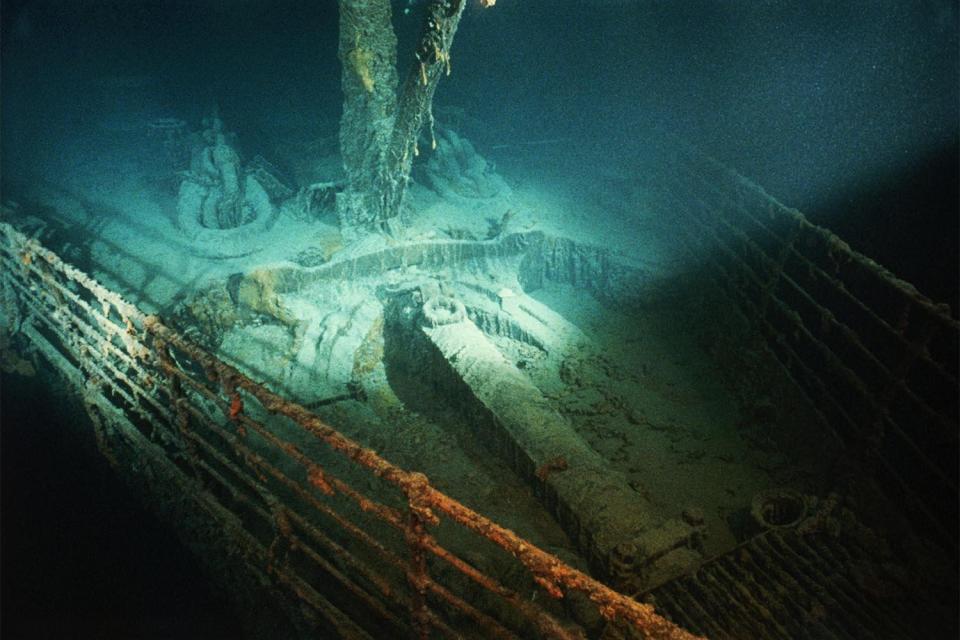

Getty A spare anchor sits in its well on the forepeak of the shipwrecked Titanic.

Astor mentioned his wife's "delicate condition" when asking an an officer if he could take one of several empty seats in her lifeboat, but the officer refused. Astor took it like a gentleman. He lit a cigarette and tossed his gloves to his wife. Several days later his partly crushed, soot-stained body was found floating in the Atlantic with $2,500 in a pocket. Experts believe Astor may have been hit by a falling smokestack.

In the years that followed, Mrs. Astor, who was twice remarried and died in 1940, rarely spoke of the tragedy, except to recall her final memory: Kitty, on deck, pacing frantically. On Aug. 14, 1912, she named her newborn son, a future playboy, John Jacob Astor V.

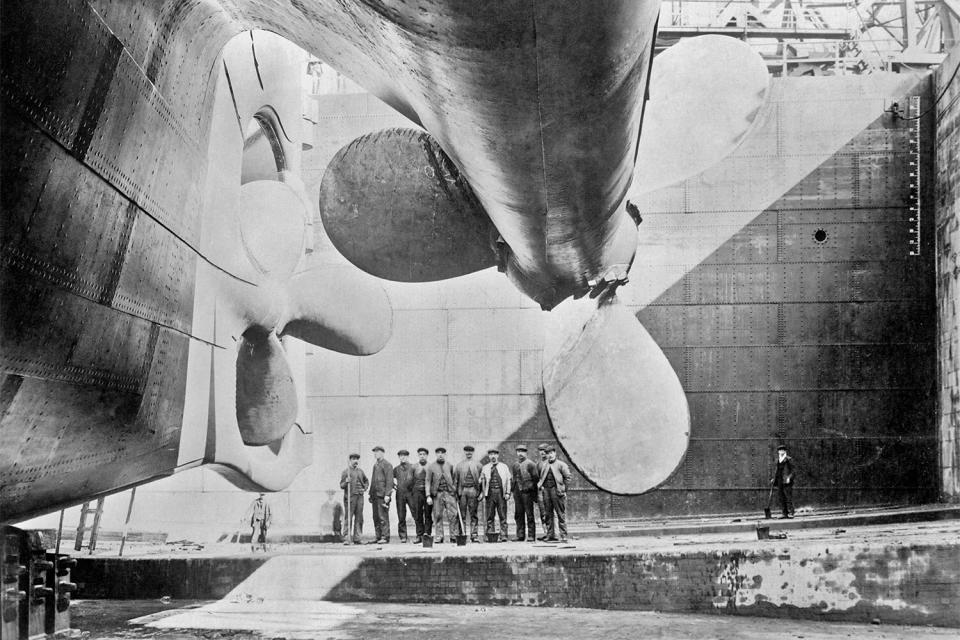

Getty This vintage photo shows the RMS Titanic's propellers as the ship sat in a dry dock.

DOUGLAS SPEDDENA — A life cut short for a boy with a bear

For 7-year-old Douglas Spedden, life was one big, if sometimes lonely, adventure. His parents — Frederick, who had inherited a banking fortune, and Daisy, a shipping heiress — spent much of the year traveling to exotic locales with their only child. But nothing could have prepared Douglas for what lay ahead as he boarded Titanic with his parents, a maid, his nanny and his best friend, a stuffed white bear named Polar.

An hour after Titanic struck the iceberg, the entire party escaped the ship in lifeboat No. 3. Clutching Polar, Douglas slept as Titanic went down. By the time he woke, the rising sun illuminated the icebergs around them. "Look at the beautiful North Pole," the boy cried, "with no Santa Claus on it!"

Back home in Tuxedo Park, N.Y., the family tried to put the disaster behind them. "The daily incidents, which once seemed of such importance," Daisy wrote in her diary, "dwindled into mere trivialities." Yet another tragedy awaited. In 1915, Douglas died in a car accident near the family's summer house in Maine.

Daisy and Frederick both died in old age, just a few years apart — but that's not where their story ends. Several years ago a distant relative discovered a storybook Daisy had written for Douglas in 1913, recounting the Titanic voyage through the eyes of a little boy's toy. Since it was published in 1994, Polar the Titanic Bear has sold 250,000 copies, ensuring that the story oflittle Douglas Spedden — like the tale of Titanic itself — will live on.

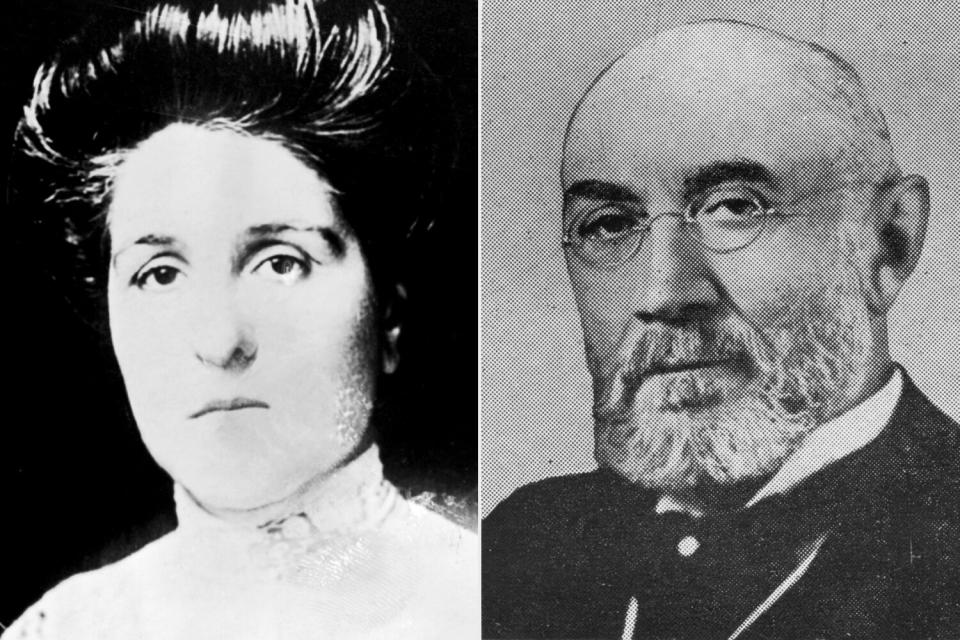

Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive/Getty; Universal Images Group/Getty Ida Straus and Isidor Straus

ISIDOR AND IDA STRAUS — Inseparable in life, then in death

Ida Straus refused at least two opportunities to escape the sinking Titanic, choosing instead to die with her husband of 41 years, a well-known philanthropist who owned Macy's department store. News that the couple had shared their fate came as no surprise to their six children and many friends. "When they were apart, they wrote to each other every day," says Joan Adler, director of the Straus Historical Society. "She called him 'my darling papa.' He called her 'my darling momma.'" For years they had even celebrated their different birthdays on the same day.

As the Titanic went down, Ida, 63, resisted the pleas of officers to climb into a lifeboat, insisting instead that her maid take her place and handing the young woman her fur coat ("I won't need this anymore," she said). She was finally cajoled into boarding the second-to-last lifeboat, only to clamber out again as Isidor, 67, stepped away. Last seen clasped in an embrace, Ida and Isidor are memorialized in a Bronx cemetery with a monument inscribed, "Many waters cannot quench love, neither can the floods drown it."

SIR COSMO AND LADY DUFF GORDON — A lady's careless words came back to haunt her

As the Titanic slipped beneath the North Atlantic, London-born Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon, a dress designer with chic shops in London and New York City, turned to her secretary aboard lifeboat No. 1 and said, "There is your beautiful nightdress gone."

Lucy's ill-timed comment, uttered over the screams of 1,500 victims stranded in the water, started a fateful chain of events. "Two of the sailors said, 'It's all right for you — you can get more clothes, but we have lost everything,'" reports Sir Andrew Duff Gordon, Lucy's great-nephew. Her sympathetic husband, Sir Cosmo, who had been given the nod to get into the lifeboat with his wife, later gave each of the seamen 5 [pounds]($360 today) to replace their belongings — a gesture that inadvertently sealed the couple's fate.

RELATED: Here Are All the Celebrities Obsessed with Titanic

Back in London, gossipy members of society accused Duff Gordon of bribing the crew to row the two-thirds-empty craft from the scene without helping victims in the water. In May 1912, a British inquest cleared Duff Gordon of the charge. But the damage to the couple's reputation was permanent. Shunned in some circles, the Duff Gordons, who were unable to have children, drifted apart, though they never divorced. Cosmo died in 1931. Lucy's business thrived for a time but went bankrupt before her death in 1935. For them at least, says Lucy's biographer Meredith Etherington-Smith, "it was almost worse to survive than to go down."

Topical Press Agency/Getty Benjamin Guggenheim

BENJAMIN GUGGENHEIM — A playboy determined to die with panache

After being informed that the ship would go down, Guggenheim — industrialist, father of three and noted playboy — calmly returned to his stateroom with his valet and donned his dinner suit. "We've dressed in our best and are prepared to go down like gentlemen," Guggenheim, then 47, told a steward after refusing a life jacket. "Tell my wife in New York I did my best in doing my duty."

The sixth of seven sons sired by Swiss immigrant andiron-smelting baron Meyer Guggenheim, Benjamin had boarded Titanic in Cherbourg with his latest in a long line of mistresses, French singer Leontine Aubart. Having been assured that she and her maid were safely aboard a lifeboat, Guggenheim and the valet reconvened on deck, where legend — and Hollywood — have them sipping brandy and smoking cigars as the ship sank.

As the rescue ship Carpathia sailed into New York harbor, three of Guggenheim's nephews rushed to the dock with his wife, Florette, who was fortunately out of earshot when an officer introduced a young blonde woman stepping off the ship as "Mrs. Benjamin Guggenheim." The real Mrs. Guggenheim was used to long periods without her husband, who spent months abroad, living lavishly and, as it turned out, squandering an estimated $8 million on bad investments. His noble death may have been a credit to his superrich family, but Guggenheim left his three children only $450,000 each, prompting daughter Peggy to later complain that she "felt like a poor relation."

George Rinhart/Corbis/Getty J. Bruce Ismay

J. BRUCE ISMAY — History would hold him responsible

"People want someone to blame," notes Michael Manser, whose great-uncle, chairman of the company that owned Titanic, has filled that role in most accounts of the liner's last hours. No one will ever know whether Ismay, who sketched the first plans for Titanic on a dinner-party napkin, told Captain Smith to rev up the engines to arrive in New York early for publicity's sake — as does the movie's Ismay. What's certain is that the chairman, then 49, escaped in one of the last lifeboats, leaving behind a shipload of passengers, his butler, his secretary and his reputation.

"There were no more passengers on the deck," he insisted later. Rescued by Carpathia, Ismay spent the rest of the trip in seclusion. While he was not formally found culpable, he was savaged by the papers ("J. Brute Ismay," taunted one) and, some say, ostracized in London society. In 1913, Ismay stepped down as chairman of the White Star shipping line once owned by his father and later retired with his American wife, Julia Florence, to western Ireland, where he died of a stroke in 1937. Manser maintains Ismay acted honorably on Titanic and was anything but reclusive afterward. Still, he realizes that foremost people Ismay remains a scapegoat. "It's nice," he says dryly, "to have a baddie in the films."

Ullstein Bild/Getty E.J. Smith

CAPTAIN E.J. SMITH — Titanic's enduring enigma

Four months before the sinking, Smith was toasted by wealthy New Yorkers at a dinner in his honor. Known as "the millionaire's captain," he was one of the most experienced and charming shipmasters on the Atlantic run. So why did Smith steer his fully loaded ship at high speed through a field of icebergs in the middle of night? The captain took the answer with him to the bottom of the Atlantic, but nothing in his past suggests a reckless streak.

Edward John Smith was born in landlocked Staffordshire, England, in 1850 and went to sea in his teens as a "boy" on a sailing ship bound around the globe and captained by his half-brother Joseph. As a captain, he joined the WhiteStar Line in 1880 and eventually skippered the maiden voyages of many of the line's newest steamers, including Titanic's sister ship, Olympic. Once, while Smith was at the helm, the Olympic mysteriously struck an object while crossing the Atlantic and had to be taken to a Belfast shipyard for repairs to a propeller.

Smith, married with one daughter, was contemplating retirement after the Titanic crossing. But given what happened, says a distant relative, Pat Lacey, 75, "it's a jolly good job he went down with her instead."

RELATED VIDEO: Titanic Revisited for the First Time in 14 Years

DOROTHY GIBSON — The silent-film star dressed for disaster

For a moment, it looked as if one of the lifeboats would follow Titanic to the bottom. Water gushed through a hole in the bottom until, in the words of Gibson, a 28-year-old silent-screen actress from Hoboken, N.J., who was aboard with her mother, Pauline, "this was remedied by volunteer contributions from the lingerie of the women and the garments of the men."

In 1914 she married Jules Brulatour, the wealthy New York film distributor with whom she had been having a long-term affair and who had called her back from her European vacation just days before she boarded Titanic. The unhappy union ended in divorce two years later. Gibson, "a very vivacious sort," according to historian Don Lynch, died of a heart attack in Paris in 1946. Many remembered the actress for her starring turn in Saved from the Titanic, a silent film made one month after Gibson was rescued. Her costume: the very dress she had worn the night of the disaster.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Frederick Fleet

FREDERICK FLEET — A lookout lived to meet a tragic end

It was in the last half hour of his watch on April 14, 1912, that Seaman Fleet, 25, in the crow's nest 50 feet above the Titanic's deck but with no binoculars (inexplicably, they had been misplaced in Southampton), spied a massive iceberg no more than 500 yards away.

In desperation, Fleet phoned the bridge. "Iceberg, right ahead!" he cried. As he braced for the worst, the ship began to turn, narrowly avoiding a head-on collision. The gentle impact, which sheared a little ice onto the deck, led Fleet to assume, as he later told a U.S. inquiry, that they had survived "a narrow shave." Some two hours later, as the ship sank, Fleet rowed a lifeboat of women to safety.

Fleet worked at sea until 1936 and in his final years sold newspapers ("just to while away the time," he said) in his home of Southampton, where he spent most nights drinking beer alone at the local workingmen's club.

"He seemed a sad, lonely man," says Titanic historian Brian Ticehurst. "His wife, Eva, was the only person he related to." Shortly after her death in 1965, Eva's brother, whose house the couple had shared, asked Fleet, 76, to move on. "The next morning," says Ticehurst, "the brother-in-law pulled open the curtains," and found Frederick had died of suicide.

RELATED: Warning Signs to Look for If You Are Concerned Someone Is Suicidal

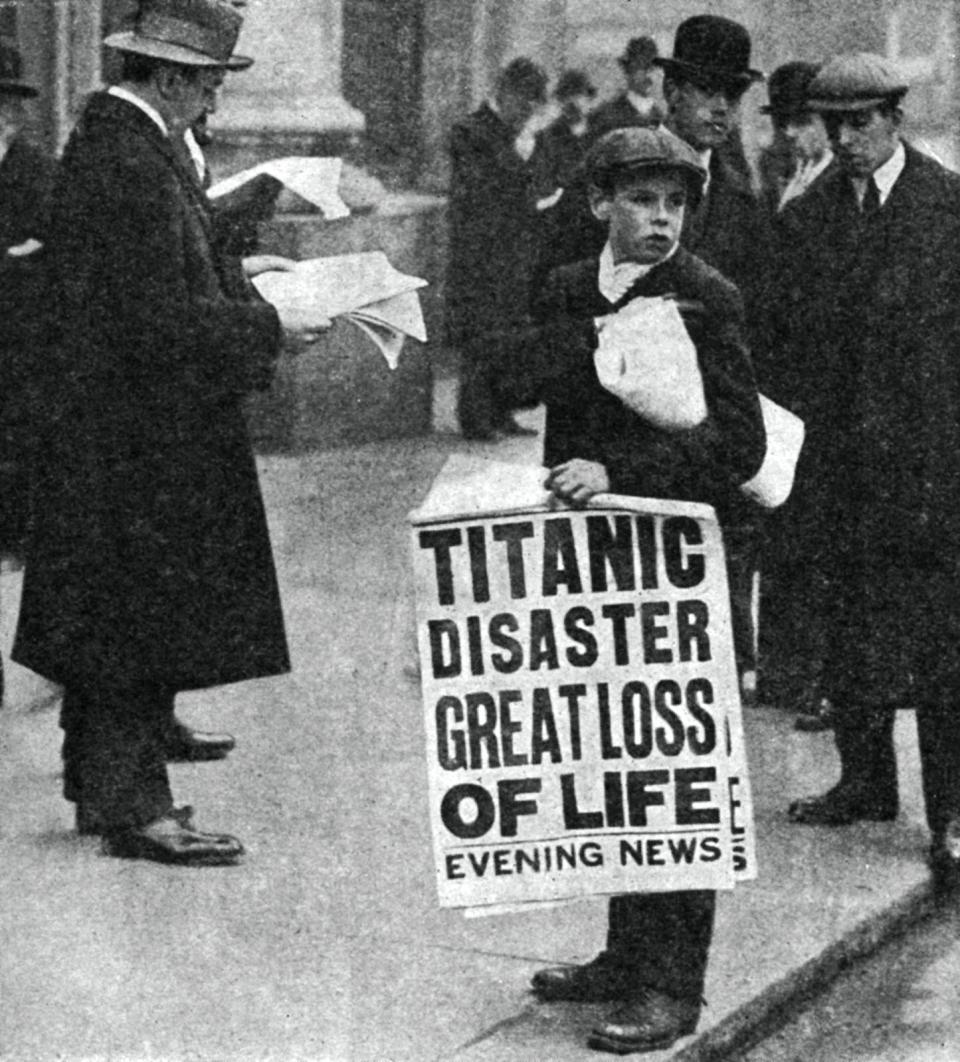

Print Collector/Getty A newspaper boy spreads news of the Titanic tragedy in April 1912

WALLACE HARTLEY — As the waters rose, the violinist made sure the music never stopped

There was music. On that much witnesses of the fateful might agree. An eight-man band led by violinist Wallace Hartley continued performing as chaos reigned. What they were playing, especially just before Titanic slipped beneath the surface, is a source of long-running debate. Favorite styles of the time were certainly on the evening's program: rags, waltzes and church hymns. But both romantics and the popular press of the day preferred to believe that the last dirge was "Nearer, My God, to Thee." In past voyages, Hartley reportedly confided to bandmates that if the ship sank he would play either "Nearer, My God, to Thee" or "O God, Our Help in Ages Past."

As a devout Methodist, his selection was hardly surprising. Hartley was born in Colne, England, in 1878, the son of an insurance salesman. He took up the violin in school and found steady work playing on ships, making some 70 voyages on luxurious ocean liners. Ironically, he tried to skip the Titanic crossing. Recently engaged to Maria Robinson, a girl from Boston Spa, north of London, Hartley was loath to leave. But he thought playing on the greatest ship of the day would give him good contacts for future work. "He was thinking of giving it up, but with the Titanic, he was persuaded to come back," says Darran Ward, a Colne historian working on a book about Hartley.

His courageous, and final, performance did not go unheralded. "He was immediately labeled a hero," says Ward. The people of Colne erected a 10-foot bust in Hartley's honor, and 40,000 mourners attended his funeral. "In the best Edwardian tradition, he put duty before self," says actor Jonathan Evans-Jones, who played Hartley in the film. "Then again," he adds wryly, "he did stand very little chance of getting into those boats."

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), text "STRENGTH" to the Crisis Text Line at 741-741 or go to suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

WRITTEN BY Patrick Rogers, Anne-Marie O'Neill and Sophfronia Scott Gregory

REPORTED BY Simon Perry, Bryan Alexander, Johnny Dodd and Julie Jordan