What 100+ pages found in Philly say about Jonathan Dickinson's perilous trek in Florida

Scholars have published a new, expanded narrative of the ordeal of a 17th-century merchant with a big South Florida connection. His name: Jonathan Dickinson.

His journal details his October 1696 planned voyage from Jamaica to Philadelphia, cut short by a shipwreck off present-day Hobe Sound — thus the state park named for him — and followed by a treacherous two-month trek to North Florida.

The journal provided the only comprehensive first-hand description of peoples who inhabited Florida for centuries, before they were wiped out — mostly, scholars assert, from European disease.

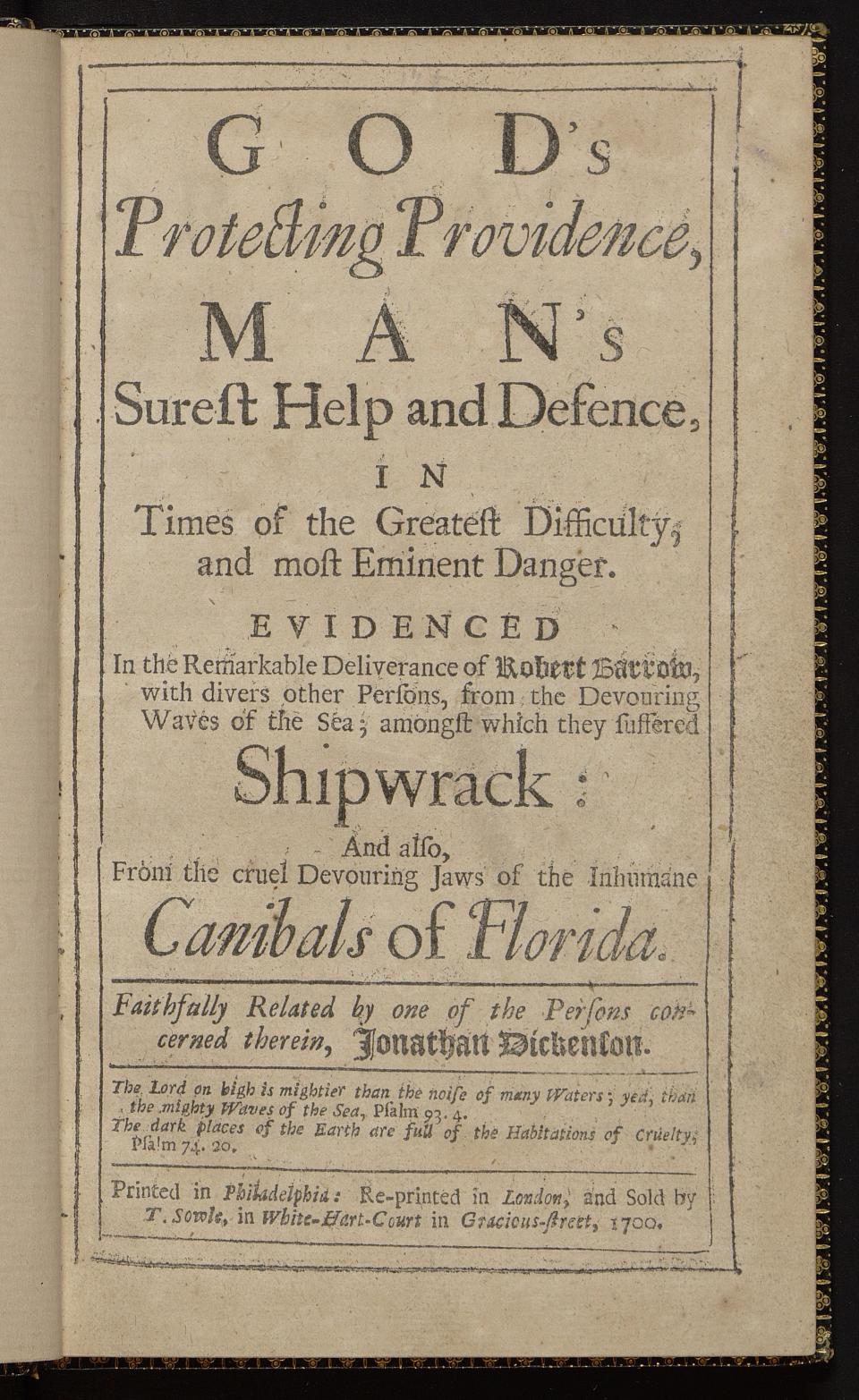

But, as the subtitle, "God’s Protecting Providence," suggests, Dickinson's Quaker editors in Philadelphia were more focused on his divine rescue.

'New material' found in 2008 in Philadelphia

A recent discovery “leaves no doubt that Dickinson’s original account was drastically cut, rearranged, and rewritten before it was approved for Quaker consumption,” the Florida Historical Society said in a summary of the new volume it has published.

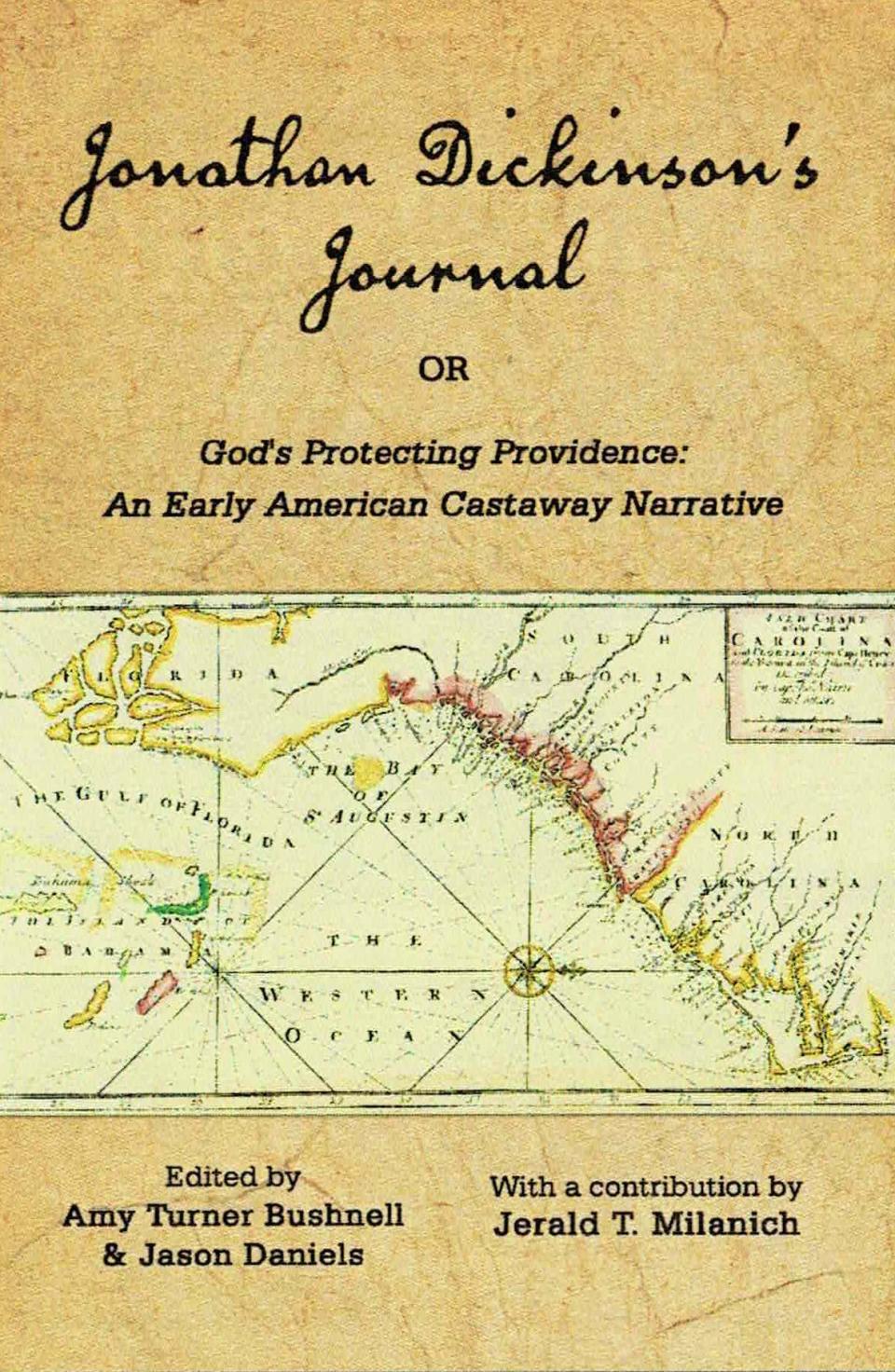

That book, titled "Jonathan Dickinson’s Journal or God’s Protecting Providence: An Early American Castaway Narrative" was produced by former Indian River Community College professor Jason Daniels and Amy Turner Bushnell, a researcher associated with Brown University in Rhode Island. It’s a combined volume of the original journal and a 111-page manuscript Daniels stumbled across around 2008 in Philadelphia.

The first edition, from 1699, would be reprinted 16 times in English and three times each in Dutch and German. Bookstores and outlets continue to sell a 1985 abridged version of a 1945 scholarly publication.

"We thought: It's been 70 years. It might be time to revisit this,” Daniels, now teaching in California, said this summer.

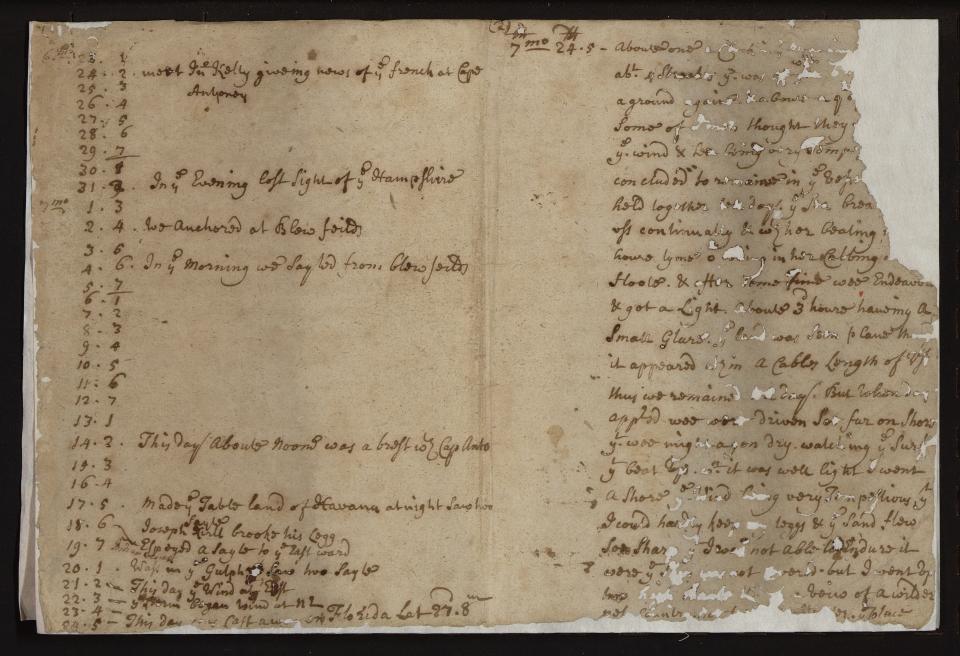

Daniels had found the manuscript while researching Dickinson's holdings at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Its title: "Journal of the Travels of several persons their sufferings-being cast away in the gulph among Cannabals of Florida."

The 1699 publication’s full title is a lot longer: "Jonathan Dickenson, God’s Protecting Providence, Man’s Surest Help and Defence in Times of the Greatest Difficulty, and most Eminent Danger. Evidenced in the Remarkable Deliverance of divers Persons, from the Devouring Waves of the Sea; amongst which they Suffered Shipwrack: And also, From the cruel Devouring Jawes of the Inhumane Canibals of Florida. Faithfully Related by one of the Persons concerned therein, Jonathan Dickenson."

It details a grueling and perilous 230-mile journey by boat and on foot through the open ocean, beaches, jungles, and swamps before the group arrived in St. Augustine. It also covers the ensuing sea voyages to South Carolina and then to Philadelphia.

Dickinson delivers more details on the Ais, Hobe and Jeaga people

The newly discovered manuscript, Daniels said, is as long as the original, but it covers just the part from Jamaica to St. Augustine, and so has a lot more detail about the early peoples.

"Almost everything we know about the Ais, and Hobe, and Jeaga, comes from Dickinson's narrative, and with this new manuscript, we have a little more information than we had,” Daniels said. That includes Dickinson’s commentary on family and marriage traditions, possessions, and ceremonies.

At the time, Europe had gone all-in on the image it had created of native North Americans as “bloodthirsty pagan cannibals,” Daniels wrote in 2013 in the Florida Historical Quarterly. He said Dickinson ”glossed over the kindness of Native Americans in the published account in order to highlight his dire circumstances and the glory of God’s deliverance.”

Dickinson had described the first locals he encountered as naked except for straw coverings, their long hair fastened in back with carved bones. They had held knives to the castaways — Dickinson, along with his wife, infant son, two associates, 10 slaves and nine sailors. The chief eventually allowed the party to leave.

The Jeaga “ordered the party to unlock their chests, trunks, and boxes,” Amy Turner Bushnell wrote in 2013 for the magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities. “The chief took the money; the warriors divided the clothes, including some that the party was wearing.“

Facing deadly threats, sleeping burrowed into the sand

The Jeaga hosts warned that people to the north would kill the castaways on sight. At night, the group built fires and burrowed into sand to escape the torment of sand flies and mosquitos.

They ran into members of the Santaluces group, armed with bows. Their clothes were torn from them and they were pelted with rocks and fists. They were forced to lie amid garbage and scorpions and spiders. But after an hour, they were given local clothing and a meal and allowed to leave.

At the next settlement, that of the Ais, the chief bathed the sunburned feet of Dickinson’s wife and offered to take the group to St. Augustine. Later, he brought to them a squad of Spanish soldiers, who the group persuaded to take them to the next town. Their only rations for the two-week trek: a bagful of berries.

Amid cold, five members of the group died of exposure in a single day. They finally staggered into the colonial capital, where they received food, clothing, and lodging, then boarded a ship for Charleston, South Carolina, and then another to Philadelphia, their original destination. They arrived in April 1697 — some seven months after they’d left Jamaica.

“I hope,” Dickinson concludes, “that I with all those of us that have been spared hitherto, shall never be forgetful nor unmindful of the low estate we were brought into; but that we may double our diligence in service there, lord God, is the breathing and earnest desire of my soul. Amen.”

More information

"Jonathan Dickinson’s Journal or God’s Protecting Providence: An Early American Castaway Narrative," Florida Historical Society Press: myfloridahistory.org/fhspress

Jonathan Dickinson State Park: 16450 SE Federal Hwy., Hobe Sound 33455. Open 8 a.m. to sunset, year-round. 772-546-2771. floridastateparks.org

Retired Palm Beach Post staff writer Eliot Kleinberg produced the "Post Time" and "Florida Time" history columns. He also is published by Florida Historical Society Press.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Dickinson journals provide fodder for new account of his Florida trek