10 Mind-Blowing Miles Davis Collaborations

The post 10 Mind-Blowing Miles Davis Collaborations appeared first on Consequence of Sound.

The Opus: Bitches Brew premieres March 19th, and you can subscribe now. To prepare for the new season, stream a legacy edition of Mile Davis’ Bitches Brew via all major streaming services. You can also enter to win the massive 43-CD The Genius of Miles Davis box set, which includes the four-disc The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions.

Spotify | Google Play | Stitcher | Radio Public |

RSS

Follow on Facebook | Podchaser

In addition to being one of the most important musicians of the 20th century, Miles Davis was a fountain of great quotes. Like Winston Churchill or Muhammad Ali, Davis had a lightning-quick wit that lent itself to hilarious boasts and withering put-downs alike. In more ways than one, he was gifted at blowing his own horn. As he memorably told off one naysayer at a White House dinner: “I changed music five or six times.”

Of course, he didn’t do it alone. In the studio and on the stage, Davis played with dozens, if not hundreds, of seasoned musicians, some of whom could even be regarded as artistic equals: Charlie Parker, the bebop trailblazer with whom Davis played some of his earliest professional gigs, and John Coltrane, whose rippling sheets of sound pushed jazz into the avant-garde, come to mind. But even if the vast majority of the trumpeter’s sidemen didn’t leave as deep an impact on jazz as Davis did, they certainly left an impact on Davis, who was constantly absorbing new sounds and influences throughout his five-decade career.

There’s never a bad time to celebrate Davis’ achievements, but in recognition of the 50th anniversary of Bitches Brew — one of the five or six times Davis changed music — we’ve assembled a decet of the man’s most interesting collaborators. In addition to a few words about each musician and their relationship to Davis, we’re recommending one of their albums for you to check out. (We left Parker and Coltrane off the list because you should already be familiar with their work. If you’re not, start with Charlie Parker With Strings and A Love Supreme.) From the birth of the cool to the warm, electric grooves of fusion, to tell the story of Miles Davis is to tell the story of jazz. Here are 10 of the artists who helped him write it.

–Jacob Nierenberg

Contributing Writer

Chick Corea

As the son of a Dixieland trumpeter, it’s fair to say that pianist Armando Anthony “Chick” Corea was born with jazz in his blood. Unsurprisingly, he began playing piano (and drums) as a child, studying with revered concert pianist Salvatore Sullo before performing in several ensembles while at Columbia University and Juilliard. From there, he’d create many studio albums with many accomplished performers, from his 1968 solo debut, Tones for Joan’s Bones, to last year’s Antidote alongside The Spanish Heart Band. That said, Corea is likely best known for being the founder and leader of jazz fusion pioneer Return to Forever, with whom he released several illustrious albums between 1972 and 1977. Of course, those works — and pretty much everything else he was doing around that time — may never have happened if he hadn’t played with Davis first.

Corea started playing with Davis (whose influence he’d later call “constant” and “a touchstone”) in 1968, when he replaced Herbie Hancock during the recording sessions for Filles de Kilimanjaro. Afterward, he’d play on several more Davis standards, such as In a Silent Way, Bitches Brew (with future Return to Forever drummer Lenny White), and On the Corner, in addition to several major live records. Be it his grounded counterpoints on “Frelon Brun”, his dissonant accentuations on “Yesternow”, or his smoothly complex playing on “Sanctuary” (alongside another jazz fusion progenitor, Weather Report co-founder Joe Zawinul), Corea always showed wisdom, patience, and selflessness when he worked with Davis. It’s no wonder he became one of the most championed pianists to ever play with him.

Essential Chick Corea Album: There are many to choose from, but it’s hard to beat Return to Forever’s seminal third release, 1973’s Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy. It’s considered a pinnacle album of the style, and for good reason: the title track alone is a tour-de-force of mesmerizing rhythmical intricacy and punchy guitar and piano riffs; “Captain Señor Mouse” finds Corea fascinatingly changing his tempo and timbres fairly often; and “The Game Maker” closes it off with a masterful frenzy from start to finish. You really can’t go wrong with it. –-Jordan Blum

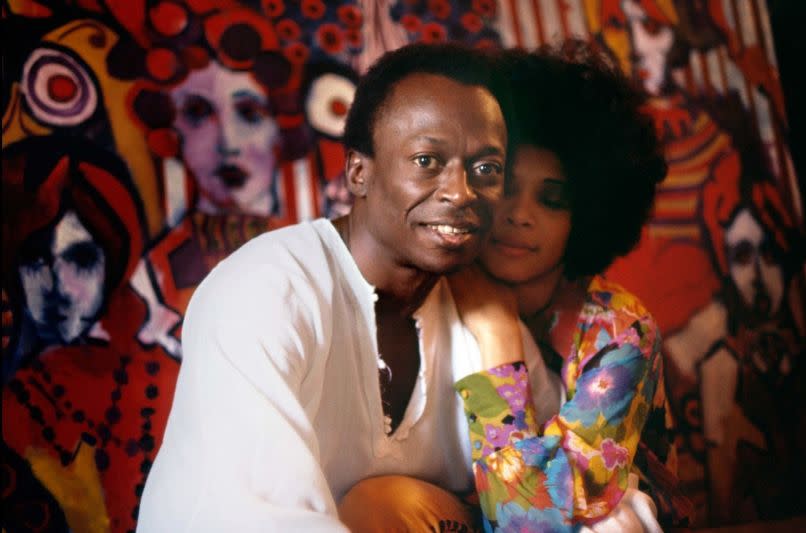

Betty Davis

Miles Davis and Betty Davis

Betty Davis (née Mabry) never recorded a note of music with her husband, but she stands as one of his most important collaborators. Nineteen years Miles’ junior, Betty introduced him to a new generation of Black musical geniuses, including Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone. Though their marriage lasted just one year (they remained close until his death), Miles’ exposure to the sounds of rock and funk rewired his musical circuitry for good; Nefertiti, the final album Miles completed before he and Betty began their relationship, would also be the final album he recorded entirely on acoustic instruments. Like Bob Dylan before him, Miles went electric, leaving a traditionalist’s ideas of jazz behind and creating music that smashed the boundaries between it and other genres to bits.

In a more just world, Betty would be known not just as Miles’ muse, but as her own musician. Betty released three albums in three years in the 1970s, getting down with the likes of Herbie Hancock and Carlos Santana, the latter of whom referred to her as “the first Madonna, but Madonna was like Donny Osmond by comparison.” Indeed, Betty’s style and overt sexuality were years ahead of their time — too many years ahead for the radio, who blacklisted Betty under pressure from religious groups and even the NAACP. (Even Miles, years after their divorce, referred to his ex-wife as “too young and wild” in his 1990 autobiography.) Betty retired from the music industry in 1979, but her albums were reissued by Light in the Attic Records in the 2000s, reasserting her as a feminine funk visionary who could have been as big as Janet Jackson or Janelle Monáe.

Essential Betty Davis Album: All three of Betty’s original albums — and a long-lost fourth, recorded in 1976 but shelved until 2009 — are worth checking out, but the best entry point is her self-titled debut. The free-spirited opener “If I’m in Luck I Might Get Picked Up” was Betty’s biggest hit, reaching the No. 66 spot on the Billboard R&B chart. Recorded with the help of members of Santana and Sly & The Family Stone, Betty Davis is nasty in all the best ways, offering kiss-offs (“Anti Love Song”) as well as come-ons (“Game Is My Middle Name”). Listen, and wonder what might have been. –Jacob Nierenberg

Gil Evans

“My best friend is Gil Evans,” Davis once said of the Canadian-American pianist and arranger. The two met in 1948, prior to recording songs that would be released nine years later on Birth of the Cool. At that same time, Davis was getting tired of recording and touring with his Quintet and wanted to try something else and decided to reteam with Evans. The resulting albums — Miles Ahead, Porgy and Bess, and Sketches of Spain — are among Davis’ most acclaimed, synthesizing jazz and classical. The bossa nova-inflected Quiet Nights (unfinished and underrated) was their final album together, but not their final collaboration, as Evans contributed arrangements to Filles de Kilimanjaro and Star People.

Beyond his arrangements for other artists (which include Charlie Parker, Johnny Mathis, and Astrud Gilberto), Evans recorded more than 40 albums, both live and in the studio, over 30 years. Like Davis, he had a musical epiphany upon listening to Jimi Hendrix, and his subsequent albums saw him exploring the sounds of jazz fusion. Evans stayed busy right up until his death in 1988, performing weekly shows at the Sweet Basil jazz club in New York City for nearly five years and collaborating with Sting and Maria Schneider (who would go on to become an acclaimed bandleader in her own right) in 1987.

Essential Gil Evans Album: Evans had hoped to record with Hendrix, but the guitarist died in 1970, before any collaboration could take place. Four years later, Evans paid tribute to Hendrix with an album of covers of his songs. The appropriately titled The Gil Evans Orchestra Plays the Music of Jimi Hendrix reinterprets beloved singles (“Foxy Lady”, “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)”) and deep cuts (“Castles Made of Sand”, “1983… (A Merman I Should Turn to Be)”) alike, to splendid effect. Even if you’ve heard these songs dozens of times, it’s a thrill to hear what Evans does with them. –Jacob Nierenberg

Herbie Hancock

Another one of Davis’ most well-known pianists (in addition to being an accomplished bandleader and actor), Herbie Hancock was labeled a child prodigy for his ability to play classical pieces by greats like Mozart. Although he looked to jazz titans Chris Anderson, Coleman Hawkins and Donald Byrd for influence and instruction, Hancock also developed his skills by listening to a lot of recorded instrumentalists and vocal groups, such as the Hi-Lo’s. His first solo album, Takin’ Off, caught the attention of Davis, who asked him to join his Second Great Quintet — which also included bassist Ron Carter, saxophonist Wayne Shorter, and drummer Tony Williams — in May 1963.

As part of that troupe, Hancock played electric keyboards and acoustic piano. He helped Davis finish Seven Steps to Heaven and make E.S.P., Sorcerer, and Nefertiti quite bold and beloved. Although he was replaced by Corea in 1968 (during the Filles de Kilimanjaro sessions), he nonetheless appeared on future LPs like In a Silent Way, On the Corner and A Tribute to Jack Johnson. His dynamic intensity throughout “Right Off” is a personal favorite, and he remained good-natured and appreciative of Davis’ impact on his career, to the point that he subsequently paid homage to Davis on records like A Tribute to Miles and Directions in Music: Live in Massey Hall.

Essential Herbie Hancock Album: Perhaps it’s the cliché choice, but 1973’s Head Hunters is rightly seen as a pivotal example of jazz funk. (In fact, it was featured in Rolling Stone’s 2003 list of the “500 Greatest Albums of All Time.”) It starts with the lengthiest and more important composition, “Chameleon,” a welcoming yet otherworldly voyage of twangy tones, smooth vibes, and organic evolutions. Obviously, that’s not to devalue the sax and woodwind delights of “Watermelon Man” (which originally appeared on Takin’ Off), the cinematic turmoil of “Sly”, or the relatively mellow and symphonic “Vein Melter”. Combined, they make Head Hunters incredibly diverse and infectious. –Jordan Blum

Teo Macero

Attilio Joseph “Teo” Macero just might be the most important name on this list, even if you don’t recognize it. As a producer for Columbia Records, Macero mixed and engineered countless classics. You’ve almost certainly heard something he had a hand in making: the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s Time Out, Thelonious Monk’s Monk’s Dream, Charles Mingus’ Mingus Ah Um, even Simon & Garfunkel’s soundtrack to The Graduate. On a list of the most important producers ever, he’d be up there with Phil Spector and George Martin.

Macero, then, was the Martin to Davis’ Beatles, helping the musician recreate the sounds in his head in the studio. With relatively few exceptions, Macero produced nearly everything Davis recorded between 1958 and 1983, leaving his sonic thumbprint on more than 30 of Davis’ albums. Nowhere was Macero’s work behind the boards more essential than during Davis’ jazz fusion period: by painstakingly editing, looping, and splicing together tapes from multiple studio sessions, Macero was able to produce lengthy pieces like “In a Silent Way / It’s About That Time”, “Pharaoh’s Dance” and “Right Off” — side-long epics that weren’t composed as much as constructed. (You can read about all the tricks Macero used to make Bitches Brew here, courtesy of Paul Tingen.) Macero’s production on records like In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew wasn’t just groundbreaking; it’s impossible to imagine how these albums would have sounded, let alone been made, without him. Brian Eno himself — another of the most important producers ever — once praised Macero’s work as “revolutionary.” Coming from the man who made Another Green World and Ambient 4: On Land, that’s high praise.

Essential Teo Macero Album: Again, Macero is better known for the albums he produced than anything he recorded under his own name. The highlight of his discography is 1957’s Teo, a lovely half-hour of cool jazz in which Macero joins forces with the Prestige Jazz Quartet. In addition to Macero’s expressive saxophone, it’s a great showcase for the Quartet’s leader, vibraphonist Teddy Charles. If you’re fond of Davis’ early albums on Columbia (‘Round About Midnight through Kind of Blue), you’ll dig this. –Jacob Nierenberg

John McLaughlin

John McLaughlin is most admired as the guitarist and leader of arguably the top jazz fusion ensemble of the 1970s and 1980s, Mahavishnu Orchestra, which he founded with another Davis alumnus, drummer Billy Cobham. After studying violin and piano as a child, he tapped into different styles of guitar-playing (such as flamenco, blues, and classical — both Indian and Western) as a teenager. McLaughlin spent most of the 1960s as a session player and collaborator with legends like bassist Jack Bruce, drummer Ginger Baker, and guitarist Alexis Korner. In 1969, he joined The Tony Williams Lifetime, a jazz fusion group led by Davis’ then-drummer. Naturally, that connection helped him get on Davis’ radar.

Luckily, he was just in time to appear on formative works like In a Silent Way, Bitches Brew, A Tribute to Jack Johnson, Live-Evil, and On the Corner. Following a decade-long break, McLaughlin entered the picture again on You’re Under Arrest and Aura. Pretty much everything he played was exceptional, with Bitches Brew’s “John McLaughlin” being a clear indication of his tastefully emotive bravura. In contrast, “Ms. Morrisine” is laid-back and selfless, whereas “Violet” is piercing and seductive. Clearly, McLaughlin always knew exactly what Davis’ vision called for.

Essential John McLaughlin Album: His debut sequence, Extrapolation, definitely has some gems (the title track, “Binky’s Beam,” “This Is for Us to Share”), but it’s Mahavishnu Orchestra’s initial statement, 1971’s The Inner Mounting Flame, that reigns supreme. For one thing, the downright hypnotic “The Dance of Maya” is a staple of the group, not to mention a must-learn classic for all burgeoning guitarists in the genre. There’s also the irresistible main motif and fiery playing (of all involved) within opener “Meeting of the Spirits,” as well as the touching piano and violin interplay within the gorgeously contemplative “A Lotus on Irish Streams.” It’s a thoroughly phenomenal recording. –Jordan Blum

Marcus Miller

After a six-year hiatus, Davis returned to the studio with a new band in 1980. Among the cast of characters who appeared on his 1981 comeback album, The Man With the Horn, was bassist and multi-instrumentalist Marcus Miller, then a member of the Saturday Night Live band. (He turned 21 two weeks into the album’s recording.) Miller would play on five more of Davis’ records in the 1980s, co-producing and writing most of the music on two of them: the chilly, synthetic Tutu and the organic, funky Amandla.

Miller has had an absurdly prolific career, scoring more than two dozen films and playing on more than 500 recordings by the likes of Donald Fagen, Aretha Franklin, and Luther Vandross, to name a few; more recently, he appeared on our favorite album of the 2010s. He’s won two Grammys and was deemed Most Valuable Player three years in a row by the Recording Academy (which led to his retirement from eligibility). On top of all that, he hosts a semiweekly radio show, Miller Time With Marcus Miller, on Sirius XM.

Essential Marcus Miller Album: One of Miller’s Grammy wins came from M2, released in 2001. The album features a murderers’ row of collaborators, from legendary R&B vocalists Chaka Khan and Raphael Saadiq to fellow Davis sidemen Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter. Miller’s band offers spirited renditions of Talking Heads and Charles Mingus, but it’s originals like “Power” and “Nikki’s Groove” that really burn down the house. –Jacob Nierenberg

Sonny Rollins

Despite being neither the free jazz innovator that John Coltrane was nor the jazz fusion pioneer that Wayne Shorter was, Sonny Rollins was one of the most technically brilliant saxophonists to play alongside Davis, which is to say he’s among the greatest jazz musicians ever. Such was Rollins’ dedication to mastering his craft that, at the height of his fame, he put his career on hold; wanting to push his musical abilities to their limits, Rollins spent two and a half years practicing along the Williamsburg Bridge for up to 16 hours a day. (His comeback album, fittingly, was named The Bridge.) He’d probably still be touring today if respiratory issues hadn’t forced him to retire in 2012 …at the age of 81.

Rollins’ time with Davis was brief, but important. He played with Davis on a number of recordings from the early 1950s, many of which were released on 10-inch LPs on Prestige Records; three of the four songs on 1954’s Miles Davis With Sonny Rollins were written by him. (Since people don’t listen to 10-inch LPs anymore, you can hear the album’s songs on Bags’ Groove.) Rollins was actually Davis’ first pick to be saxophonist when the trumpeter formed the Miles Davis Quintet in 1955, but he left a few months later to focus on breaking his heroin addiction. At his drummer’s recommendation, Davis replaced Rollins with another talented saxophonist who was yet to make a name for himself: John Coltrane.

Essential Sonny Rollins Album: They didn’t call Rollins the “Saxophone Colossus” for nothing. His album of the same name, released in 1956 (or 1957), is unanimously hailed as a masterpiece, with songs like the calypso-inspired “St. Thomas” and the brisk “Strode Rode” establishing the then-26-year-old as a major jazz artist. Saxophone Colossus ends on its highest note—closer “Blue 7” is a dazzling showcase of Rollins’ improvisational mastery, with solos so mesmerizing that jazz historian Gunther Schuller analyzed them at length in a 1958 article. –Jacob Nierenberg

Wayne Shorter

Considering that he was born in the early 1930s, it’s no shock that Weather Report co-founder Wayne Shorter rose to prominence earlier than many of the other people on this list. His older brother, Alan, was a revered jazz trumpeter (and onetime saxophonist), and it wasn’t long before Waynewas working with miscellaneous musicians as he studied music education at New York University and served in the US Army. His big break came in 1959, when he joined — and later directed — Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers on the tenor sax; five years later, he joined Davis’ Second Great Quintet.

In Len Lyons’ book The Great Jazz Pianists, Herbie Hancock praised Shorter as “the master writer to me, in that group” and “one of the few people who brought music to Miles that didn’t get changed.” Likewise, Davis, in his autobiography, called Shorter “a real composer” who “brought in a kind of curiosity about working with musical rules.” Shorter remained with Davis until 1970, leaving his mark on classics like Filles de Kilimanjaro (his final album before switching to the soprano sax), In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew. Just one listen of his soulful flourishes on “Paraphernalia” (which he wrote) or his soothingly suspenseful back-and-forth momentum with Davis on “Spanish Key”, and you’ll know why he was perfect for the job.

Essential Wayne Shorter Album: Roots & Herbs by Art Blakey & the Jazz Messengers is crucial, as is Shorter’s own Schizophrenia and his work on Joni Mitchell’s Mingus. Nevertheless — and predictably, given my biases — Weather Report’s Heavy Weather is the superlative pick. Bass maestro Jaco Pastorius makes quite an impression on his sophomore appearance with the group, displaying invaluable presence on “A Remark You Made” and “Palladium”. Everyone else shines throughout, too, of course, with Shorter really showing off on his own richly calming “Harlequin” and Pastorius’ lively closer, “Havona”. Jazz fusion may have been past its prime by then, but Heavy Weather is still a peak illustration of it. –Jordan Blum

Tony Williams

As a teen, the late drummer Tony Williams studied with influential instructor and drummer Alan Dawson and played with saxophonists Sam Rivers and Jackie McLean. Surprisingly (but deservedly), that’s pretty much all it took for the Chicago native to join Davis’ Second Great Quintet when he was only 17 years old, making him one of the youngest musicians to ever enter the Davis camp. After his tenure, he formed jazz fusion darling The Tony Williams Lifetime alongside guitarist John McLaughlin and organist Larry Young. Williams also reunited with a few other prior Davis mainstays — Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, and Ron Carter — to form the short-lived V.S.O.P. in the late 1970s.

Williams’ first studio sequence with Davis was 1963’s Seven Steps to Heaven. He subsequently appeared on monumental offerings like E.S.P., Miles Smiles, Nefertiti, and Miles in the Sky. In Davis’ autobiography, the trumpeter claimed that “the center that the group’s sound revolved around” was Williams, and he’s totally right. For instance, Williams’ tight percussion keeps his “Hand Jive” focused; his seemingly messy syncopation makes “Masqualero” rather tense; and his adaptable techniques turn Shorter’s “Footprints” (first recorded for the saxophonist’s Adam’s Apple) into a spicier and trickier beast.

Essential Tony Williams Album: I’m Old Fashioned by saxophonist Sadao Watanabe with The Great Jazz Trio certainly ranks highly, as does the lone Trio of Doom album that took almost 30 years to come out. Yet, it’s Believe It by The New Tony Williams Lifetime that gets the prize here. After the dissolution of the former ensemble, Williams recruited bassist Tony Newton, keyboardist Alan Pasqua, and guitarist Allan Holdsworth to keep the exhilarating jazz fusion and funk going. With outstanding tracks like the Stevie Wonder-esque “Snake Oil”, and the virtuosic vibrancy of “Red Alert”, they absolutely do. —Jordan Blum

10 Mind-Blowing Miles Davis Collaborations

Matt Melis

Popular Posts