Read-option star QB Reggie Collier missed NFL stardom, but at peace after conquering addiction

"You knew you were seeing something special and if you think about it, you were seeing something you hadn't seen before." – Southern Mississippi play-by-play announcer John Cox.

HATTIESBURG, Miss. – Thirty-five years. That's how long the old radio man has been hooked to that headset watching football players run across the Eagle at midfield. He's been to all the citadels of the South – Tuscaloosa, Tallahassee, Auburn's Jordan Hare – and for four autumns he chronicled a quarterback named Favre, who heaved passes from impossible angles.

But never, never, John Cox is saying, had he ever seen anything like the player who crouched behind center late in the 1979 season, grabbed a snap and then tore off for the next three and a half seasons.

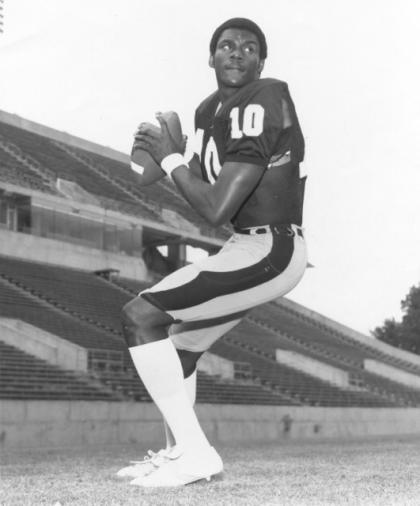

Reggie Collier didn't run as much as he galloped. His legs seemed to take 5 yards with each stride. When he threw, the ball whistled downfield. A world of stiff, standing quarterbacks or shifty little option runners had not trained Cox's eyes for something like this. It was as if the game was being reinvented before him.

"Just woooosh and he was gone to the end zone," Cox says.

[Related: Ed Reed reflects contradictions in NFL's head injury issues ]

Long before this Super Bowl and Colin Kaepernick, there was Reggie Collier. What hope did teams have when Southern Miss coach Bobby Collins rolled out the double-read option with a 6-foot-4, 215-pound giant who ran the 40-yard dash in 4.4 seconds? He'd freeze the defensive tackle, fake the end and before anyone realized it he was streaming for the end zone.

Like in 1981 when he ran for six touchdowns for more than 50 yards. Or how that year they went to Florida State, where he ran for 150 yards in a 58-14 victory against the Seminoles. Imagine that. Southern Miss beating Florida State by 44 points?

By the end of the year Collier was the first player in college football to run for 1,000 yards and pass for 1,000 yards.

"The whole posse was chasing him as he ran down the field," remembers Chuck Cook, his college teammate who is now the Buffalo Bills' scouting director.

"You didn't say one 'wow,' you said three 'wows,' " says Sirius Radio NFL analyst Gil Brandt who would later draft Collier for the Dallas Cowboys.

He seemed destined to change football forever. Only he didn't. In a large part because football wasn't willing to change. He threw 22 passes in the NFL and by the middle of the 1987 season he was done.

"I think he was ahead of his time, I really do," Cook says.

"He was Michael Vick long before Michael Vick," says Cox.

About 104 miles northeast of New Orleans and this Super Bowl of Kaepernick, Reggie Collier walks toward the field at M.M. Roberts Stadium on Wednesday afternoon. He's 51 now and his chest has filled, his body no longer the lithe weapon it was when he ran in front of these stands. "He's more like an offensive lineman now," his good friend and former teammate Sammy Winder says laughing over the phone. Collier accepts the insult with a chuckle. Better to be a little big than dead.

It has not been an easy life being ahead of his time. When the NFL didn't see him as the quarterback he saw himself, he found comfort in the bottle and drugs. The player raised on the Mississippi coast by a strict religious grandfather who thought football to be "of the world," found himself chasing women. For nearly two decades his life spiraled down, lost in the haze of the next high.

Then about 12 years ago he got himself into a facility in Houston. They helped him there. Spent nearly a year in that place and came out clear. Returned to Southern Miss and finished his degree in athletic administration. He might be proudest of that. He got married and worked for the school for a few years until the man who runs Southern Mississippi's garbage empire, Waste Pro, hired him as a division manager. Waste Pro just won the contract to pick up all Forrest County's trash. The new deal starts next week. A lot is going on back at the office with routes to finalize and drivers to train. Life is busy these days.

[

Yahoo! Sports Radio: Arian Foster compares heartaches of playoff losses]

Collier has been watching football in this season of the running-passing quarterback. How could he not? When he sees Kaepernick, he's seeing himself 30 years before. He loves these coaches now, men like San Francisco's Jim Harbaugh, who took a chance on Kaepernick and Washington's Mike Shanahan with Robert Griffin III and Pete Carroll who thought Russell Wilson was the best quarterback for the Seahawks. They're the ones with the imagination. They get it.

"You have to give these coaches credit," he says.

Then he smiles and shakes his head.

"It is what it is," he says.

He says this a lot. He says he can't go back and change life. He says there's no point. Better to look at the future.

What would have happened if Collins hadn't left to coach SMU before Collier's senior year in 1982? When he and offensive coordinator Whitey Jordan took off for Texas and Jim Carmody took over and scrapped the double-read, making it a single read, Southern Miss struggled. Teams came up with new ways to keep Collier from getting outside, spreading defensive ends wide. Nothing was as good as the year before.

But chances are it didn't matter. The NFL wasn't going to change right away for Reggie Collier. The few teams he talked to told him they wanted him to be a wide receiver or defensive back. Nobody was talking quarterback. And really, that's all he wanted to do.

He signed with the Birmingham Stallions of the USFL because they let him play quarterback, then blew out his knee three games in. Separated from the team, alone for the first time and missing his mother Brenda, who was beating a substance abuse problem, the drinking and drugs started for Collier. He tumbled through football, a fall that included a season with the Washington Federals and a year bouncing between receiver and quarterback with the Dallas Cowboys, who had held his rights after picking him in the sixth round of the 1983 draft.

Brandt remembers Collier as "raw," but "a very, very talented athletic-type quarterback."

"He could throw 50 yards with a flick of his wrist," Brandt says.

The Cowboys bought Collier a house near their practice facility with the idea he could work on his skills. But Collier never practiced hard enough. By then the drinking and drugs had taken hold. When the Cowboys finally tried Collier at quarterback, Brandt remembers him coming to the sideline after two series and telling coach Tom Landry he was tired and needed to catch his breath.

"I had never seen anything like that," Brandt says.

Nobody called him after the 1987 strike. Collier tried arena football but didn't stick. By that point he didn't stick with much of anything. He drifted around Mississippi, he went up to New York and lived in Harlem for several years. When asked what he did for most of that time, Collier laughs.

"I got high," he says.

Then he pauses.

"Let me explain," he says. "You put your most important things in life. What are they? God and family, job, finances and maybe getting high once in a while is at the bottom of the list. That would be a normal person. All right, in the mind of an addict the alcohol and the drugs slowly creep up that list to the point to where, all right, your belief in God is questioned because you wonder why God put you in this situation. Why is this like this? Your job, you will eventually lose your job because of alcohol and drugs. Your family, you will eventually lose your family. Your finances will eventually go away. So at the end of the day what do you have left? The alcohol and the drugs."

Collier stops and shakes his head.

There's something his mother used to say and he remembers it now. "If you keep going to the barbershop sooner or later you're going to get a haircut." He'd try to get away from the drugs but eventually he found his way back to old friends, old haunts. Soon he was getting high again.

It used to destroy him that Brenda saw him like this. She was always his support. After she and Collier's father divorced, Brenda's parents took Collier in and she was never far. When her father, the Bishop Robert Nance, refused to let him play sports, she sent him to live with his father.

Without Brenda there would never have been football. And without football he had ruined everything. One of his greatest regrets is that she died while he was still deep in his addiction.

"She saw what I was going through and she would do anything she could to help me," Collier says. "It ultimately falls on the shoulders of the person. I can sit here and tell you if I were to see you indulging in alcohol or drugs or whatever the case may be – if I can sit here and tell you it really doesn't do any good until you make the decision to change your life. She was telling me but I wasn't hearing. So … "

He stops.

Then he begins to cry.

If Collier has to pick one person who saved him it would be Dirk Minniefield, the former Kentucky basketball star. They met through mutual friends. And as the 1990s came to an end, Minniefield, who had substance abuse issues of his own, called the most. They talked a lot, Collier and Minniefield. They had similar burdens. Collier felt like a failure for the career that never happened just as Minniefield did in a listless handful of seasons in the NBA.

Collier had tried a few rehab facilities but they never worked. Four weeks later he was always out and hunting for drugs again. Minniefield knew of a place in Houston similar to the one run by former basketball star John Lucas, who helped him handle his own addiction. He wanted Collier to go. There were former athletes who worked there. They would understand him. So Collier went.

He wound up staying nine months.

"I had to deal with a whole lot of stuff dating back to guilt issues, being able to accept certain things, being able to accept the fact that you are an addict," Collier says. "That was kind of hard for me to accept some of those things, even dating back to stuff with my parents.

"We as athletes have been taught from Day 1, whatever is in front of you I'm going to beat it. I'm going to beat you, I'm going to conquer you. Whatever the situation is I'm going to beat it. I always feel, 'I can do it by myself, I don't need your help.' For years I would say that to myself. … I came to the realization that I need to put my pride in my pocket and be able to say, 'I need some help. I need help.' "

But this was what Minniefield had been trying to tell him; what a lot of people had been trying to tell him. He had tried to beat the NFL alone, tried to run around its system by playing in the USFL as a quarterback instead of being a receiver in the NFL. Minniefield could feel the anger in Collier. So much shame mixed with rage over the football career that never was.

It was hard to get Collier to talk about his past. He kept things close, burying his frustration. Minniefield told him he had to release that. He had to talk about the past. He had to understand why football didn't work out. Only then would life work.

[Related: Ex-Giant calls Ray Lewis a 'caricature']

"A lot of the frustration from football led to his troubles," Minniefield says over the phone. "You have all this frustration and depression you go through as a professional athlete and you have to go through that privately and publicly. You think about how many players you have seen who have changed their positions successfully – it's not many. And it's usually not because they were highly successful at that position they were playing."

Minniefield believes Collier lost his confidence when the pros weren't interested in a quarterback like him. "When that happens," he says, "you look for other outlets."

Then Minniefield, who is now a drug counselor for the NBA, thinks for a moment. Something more he wants to say, something that he thinks will explain everything.

"Reggie is a legend, just everybody forgot," he says. "He had forgotten too. I had to remind him."

If there is one thing Collier wants to make clear it is that he does not blame the NFL for his failed career. Not if he is honest with himself. He knows all the times he didn't lift weights, run or work as hard on preparing for games. He did enough personal damage with the drinking and drugs. He knows a big reason the NFL didn't call after the strike was because he had developed a reputation as someone who didn't work hard and was difficult to coach.

"But it is what it is," he says. "You can look at my situation and the situation in the whole league. There were only three black quarterbacks who were playing at the time when I was there. Those guys were playing, I was in back of them. You look at the stuff Doug [Williams] went through in Washington. The guy was a proven quarterback. Warren Moon. With Randall Cunningham I'm pretty sure that if he wouldn't have been with Buddy Ryan – he had a different kind of thinking as a coach – who knows what would have happened."

Collier is sitting in a room behind the football field. A steady rain has been falling. For a moment he is quiet. He wonders why no one asked Steve Young to change positions. Sure the San Francisco 49ers threw a lot but Young was known as a runner just like he was. Nobody was telling Steve Young he had to be a defensive back or wide receiver.

"You don't want to say in this day and age that race doesn't have a lot to do with it but when you look at it the numbers speak for themselves," he says.

"People are not going to say it because it's not the politically correct thing to say, but look at the numbers. Who makes these determinations that a kid can't do this and he's not being given the opportunity to do this."

Collier stops. Complaining is not productive. So much is good in his life now with the big Waste Pro contract and his marriage. He is close again to his daughter, who had fallen out of his life. A few years ago Southern Miss retired his No. 10 jersey. He can see the sign on the side of the stadium stands if he looks over his shoulder. On the first floor, outside the team locker room, they have his old jersey in a ceremonial locker right beside that of Brett Favre.

He smiles.

In many ways Minniefield was right.

He is a legend. And, yes, he finally does know it.

Other popular Super Bowl content on Yahoo! Sports:

• How the Super Bowl got its Roman numerals

• U2's powerful NFL halftime shows almost never happened

• The U's super team well represented in New Orleans

• Chris Culliver issues statement after anti-gay remarks