When it's Woman (D) versus Woman (R), interesting things happen

The record number of women running for office this midterm election year has led to a record number of races in which both major-party candidates are women, creating an interesting real-world experiment in political science. With nine states still to hold primaries, there are already 28 congressional contests in which voters will choose between two female candidates, compared with a previous record of 17. While still a small percentage of all races (178 House contests are between two men, and 139 are between a man and a woman), this cluster is serving as fertile ground for researchers who study the role of gender in politics.

“It certainly is a cool time to have this as your specialty,” says Mirya Holman, associate professor of political science at Tulane University, who is studying gender stereotypes in political matchups between women.

“Races with two women have been so rare until very recently that there really hasn’t been much real-world research at all,” says Tessa Ditonto, assistant professor at Iowa State University, who specializes in gender and psychology in American politics. “Nearly all the research to this point has been theoretical, and there isn’t even much of that. This is a great chance to learn what we’ve had no data for.”

While knowledge gained from these current races won’t be complete until they are run, already it seems clear that the conventional wisdom — that gender ceases to be an issue in a race between two women — is wrong. “Just because two women are running doesn’t mean gender doesn’t matter,” says Kelly Dittmar, assistant research professor at the Center for American Women and Politics, part of the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University.

She says that as recently as three years ago she was told by one researcher, “You can make the argument that the issue of gender was removed because you have two women running for governor.”

But watching women navigate this year’s races, Holman says, illustrates that “gender still matters. It just matters in different ways than in a contest where you have a woman running against a man.”

Among the preliminary takeaways from those who are paying academic attention:

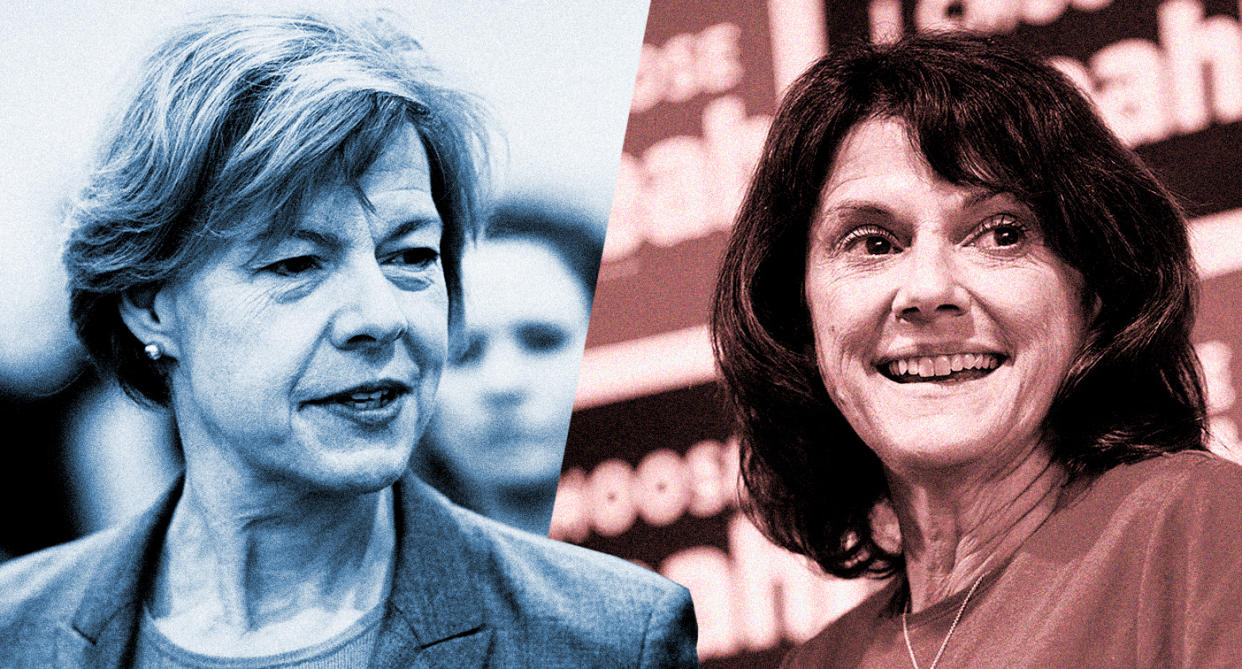

Democrats stress the presumed female trait of compassion while Republicans stress the presumed male trait of strength even when both candidates are female. In Wisconsin, for instance, Sen. Tammy Baldwin, the incumbent and the only openly lesbian senator, is running ads showing her surrounded by young children and discussing the harm done by repealing the Affordable Care Act. Her challenger, Leah Vukmir, in contrast, came out of the campaign gate with an ad showing her sitting alone at a table with a handgun in front of her, talking about the “guts” she will show standing up to threats around the world and at home.

Put another way, a woman running for office may need to establish she is just as tough as a man — but she doesn’t have to prove she is tougher than her male opponent. There is a threshold of strength that candidates have to reach for the voters to trust them. But if elections were a comparative test of strength, then you’d expect that when two women run, “toughness” would recede as an issue. That’s not what’s happening, Dittmar says. If anything, many women running against women are literally flexing their muscles more.

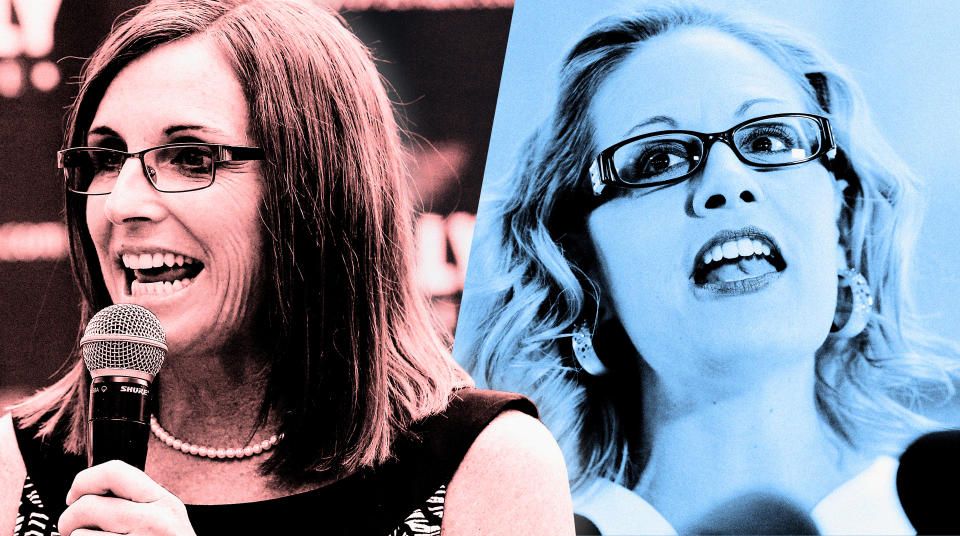

In Arizona, for instance, Martha McSally — who is leading Kelli Ward in the Republican primary for Senate and is expected to face Democrat Kyrsten Sinema should she win the primary on Tuesday — launched her campaign with an ad that resembled the movie “Top Gun,” all metallic music and quick cuts of her piloting a combat aircraft. That she underscored her point in some very female ways — “grow a pair of ovaries” is how she describes her message to many in Congress — is essentially a tweak on an established meme.

But voters perceive a woman’s “toughness” differently when the race is against another woman, so the above assumption might not hold when all the research is in. When research subjects were presented with fictional articles about fictional candidates for governor in a research study from the University of Oklahoma and the University of Washington, they preferred the one who presented as a mix of traditional masculine and feminine traits, as opposed to the one who presented as more stereotypically masculine.

In a race between two women, the Republican candidate faces a more complicated challenge. Holman notes that voters make certain assumptions about candidates based on such categories as party and gender. Republicans, in general, are assumed to be tougher and more conservative than Democrats. Men, in general, are thought to be tougher and more conservative than women. Each candidate then uses those assumptions as a foundation on which to build a winning coalition.

“For Democratic women, the challenge for them is that they have two pieces of information that cue voters to see them as more liberal — party identification and gender identification,” Holman says. “For Republican women it is the opposite. Her party label says ‘conservative’ but her gender label says that she is liberal.”

As a result, she continues, a female Democratic candidate can move to the right in the general election because her base will automatically assume, from her gender and party cues, that she still speaks for them. “Republican women, on the other hand, not only have to convince independents and Democrats that she is not too conservative, which is her party cue, but also reassure members of her own party that she’s not too liberal, which is her gender cue.” In a race between two women, she says, that gives a Democrat more room to move and maneuver.

By way of example, Holman points to the Senate race in Wisconsin. The reason Vukmir sits at a table with a handgun, Holman says, is that “she is trying to reassure her Republican base that she is conservative enough, that she knows how to navigate masculine issues, that she is ‘man enough’ for the job.” Baldwin, in turn, “can claim all the traditionally ‘Democratic’ issues plus all the issues in the middle, all while Vukmir is on the right trying to make it clear to her Republican base that she is enough of a Republican for them to vote for her in November.”

The long-standing taboo against running attack ads against a female opponent is likely dead. This has long been a fundamental truth for men who are running against women, because “there’s a concern about men looking like a bully,” Dittmar says. It is increasingly less true (see the ads by Nancy Pelosi’s Republican opponent, John Kelly, comparing the House minority leader to the Wicked Witch of the West) and, it seems, not at all true in contests between women.

True, some women candidates this season have said they’ve received advice not to go negative because it risks looking like a “catfight.” But in general, women candidates seem to feel free to attack their female opponents.

“Women are just as likely to go negative against each other as men are to go negative against men,” Dittmar says, and in this election cycle so far there has been no outcry or backlash.

In her recent book, “Navigating Gendered Terrain,” Dittmar points to the 2010 Oklahoma gubernatorial campaign, in which Mary Fallin, the Republican, was accused of fueling a whisper campaign about the sexuality of her opponent, Jari Askins, by constantly pointing out that Askins was single and childless. “I think my experience is one of the things that sets me apart as a candidate for governor. First of all, being a mother, having children, raising a family,” Fallin said in a debate.

“You know, in Oklahoma, all of our governors have been men. So none of them have been mothers,” Askins responded. “I think most of them have done a pretty good job — so I don’t think that’s a criteria.”

Fallin won that race with 60 percent of the vote and is currently completing her second term.

Looks, on the other hand, still matter. In a forthcoming paper in the Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, Ditonto and her co-author write of their study in which subjects were shown headshot photos of actual opponents in actual completed races and asked which one looked more competent and which looked more attractive. In the races where both candidates were men, the one judged more competent by the majority of research subjects was the one who had actually won. In races where both candidates were women, in contrast, the one found to be more attractive by research subjects was also the one preferred by voters.

Voters have a feeling that a certain number of women is “enough.” A separate study by Ditonto and her Iowa State co-author, David Andersen, found that the more women there were on a ballot, the more it hurt those women who were lower down on that ballot. In other words, if there was a Republican woman running for Senate or governor, it statistically decreased the odds for a Republican woman running for the House of Representatives, the state legislature or county executive.

In their study, titled “Two’s a Crowd,” the authors theorize that “this is because our stereotypes are being activated by more women running simultaneously.”

So what does that mean when the women in question are running against each other? “That’s one of the many things this year might help us figure out,” Ditonto says.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: