Exclusive: Fitbit's 150 billion hours of heart data reveal secrets about health

For something as important as heart health, it’s amazing how little you probably know about yours.

Most people probably get their heart rates measured only at doctor visits. Or maybe they participate in a limited study.

But modern smartwatches and fitness bands can track your pulse continuously, day and night, for months. Imagine what you could learn if you collected all that data from tens of millions of people!

That’s exactly what Fitbit (FIT) has done. It has now logged 150 billion hours’ worth of heart-rate data. From tens of millions of people, all over the world. The result: the biggest set of heart-rate data ever collected.

Fitbit also knows these people’s ages, sexes, locations, heights, weights, activity levels, and sleep patterns. In combination with the heart data, the result is a gold mine of revelations about human health.

Back in January, Fitbit gave me an exclusive deep dive into its 6 billion nights’ worth of sleep data. All kinds of cool takeaways resulted. So I couldn’t help asking: Would they be willing to offer me a similar tour through this mountain of heart data?

They said OK. They also made a peculiar request: Would I be willing to submit a journal of the major events of my life over the last couple of years? And would my wife Nicki be willing to do the same?

We said OK.

Oh boy.

About resting heart rate

Before you freak out: Fitbit’s data is anonymized. Your name is stripped off, and your data is thrown into a huge pool with everybody else’s. (Note, too, that this data comes only from people who own Fitbits — who are affluent enough, and health-conscious enough, to make that purchase. It’s not the whole world.)

Most of what you’re about to read involves resting heart rate. That’s your heart rate when you’re still and calm. It’s an incredibly important measurement. It’s like a letter grade for your overall health.

“The cool thing about resting heart rate is that it’s a really informative metric in terms of lifestyle, health, and fitness as a whole,” says Scott McLean, Fitbit’s principal R&D scientist.

For one thing — sorry, but we have to go here — the data suggests that a high resting heart rate (RHR) is a strong predictor of early death. According to the Copenhagen Heart Study, for example, you’re twice as likely to die from heart problems if your RHR is 80, compared with someone whose RHR is below 50. And three times as likely to die if your RHR is over 90.

Studies have found a link between RHR and diabetes, too. “In China, 100,000 individuals were followed for four years,” says Hulya Emir-Farinas, Fitbit’s director of data science. “For every 10 beats per minute increase in resting heart rate, the risk of developing diabetes later in life was 23 percent higher.”

So what’s a good RHR? “The lower the better. It really is that simple,” she says.

Your RHR is probably between 60 and 100 beats a minute. If it’s outside of that range, you should see a doctor. There could be something wrong.

(The exception: If you’re a trained athlete, a normal RHR can be around 40 beats a minute. If you’re Usain Bolt, it’s 33.)

Regular exercise is good for your heart, of course. But all kinds of other factors affect it, too, including your age, sex, emotional state, stress level, diet, hydration level, and body size. Medicines, especially blood-pressure and heart meds, can affect it, too. All of this explains why RHR a good measure of your overall health.

Fitbit’s data confirms a lot of what cardiologists already know. But because the Fitbit data set is ridiculously huge, it unearthed some surprises, too.

“I was a researcher in my past life,” says McLean. “You would conduct an experiment for 20 minutes, then you’d make these huge hypotheses and conclusions about what this means for the general population. We don’t have to do that. We have a large enough data set where we can confidently make some really insightful conclusions.”

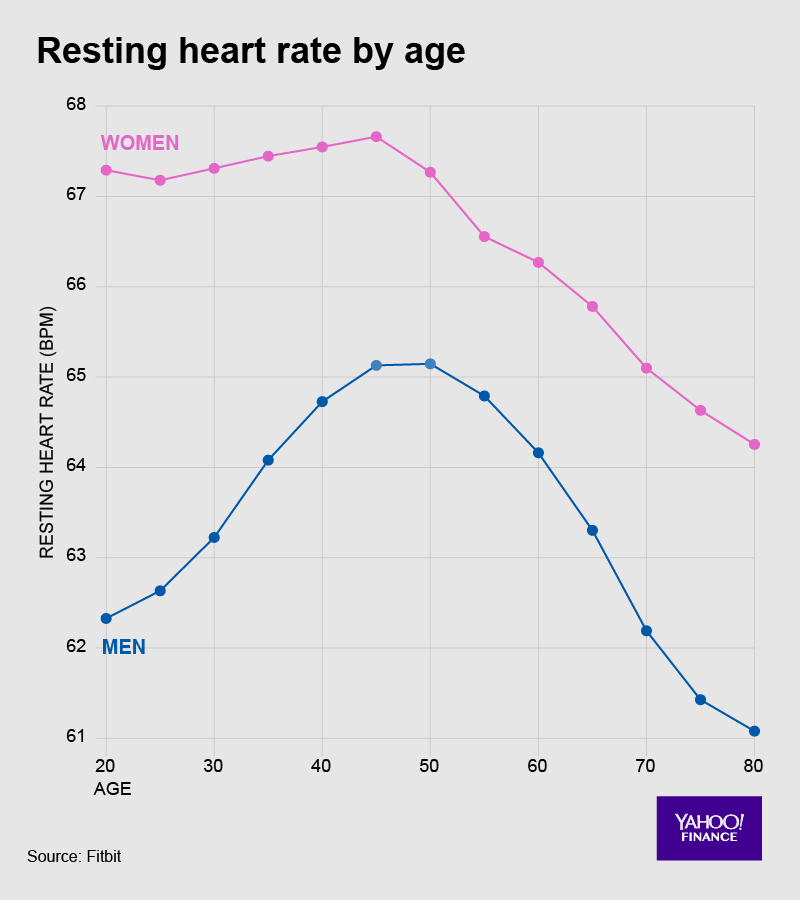

Women vs. men, young vs. old

The first observation from Fitbit’s data: Women tend to have higher resting heart rates than men.

“Because women tend to be smaller,” says Emir-Farinas, “their heart is smaller, and the heart needs to work harder to make sure that blood is circulating and it’s being provided to all vital organs.”

What’s weird, though, is that your RHR goes up as you approach middle age, and then goes down again later — and that’s something scientists hadn’t witnessed with such specificity before the Fitbit study. “This has never been reported before in the medical literature with such confidence,” says McLean.

So what’s going on? Why does your heart rate increase as you approach your late 40s?

Well, one big reason might be having kids. You get busy. You eat junkier food. You exercise less. You’re more stressed out.

And, of course, everybody’s metabolism naturally slows down — that’s why so many people gain weight around middle age. “Also, the heart itself is changing,” says McLean. “The muscle becomes weaker. Each time we contract, less blood goes into the heart.”

All of that means that that your heart has to work harder — and your RHR goes up.

OK, fine. But then why does your heart rate drop after middle age?

“We think some of the decline is attributed to the use of beta blockers and calcium channel blockers” — blood-pressure and heart-attack medicines — “because 30% of adults in the U.S. have hypertension,” says Emir-Farinas.

Otherwise, the Fitbit scientists aren’t sure what causes this effect; after all, they’ve just discovered the phenomenon. “This opens up all new possibilities to try and understand in more detail, with maybe more controlled experiments, why these things happen,” says McLean.

RHR Variation

The new data doesn’t just show our average RHR; it also shows how much our RHRs vary.

“Younger women, on average, experience a higher variation,” says Emir-Farinas. “Some of that could be explained by hormonal changes during menstruation.”

You know who else turns out to have wide swings in heart rate? Men over 50.

“It’s manopause, as my wife calls it in me,” McLean cracks. “But no, we don’t know the reason, because nobody’s really observed this before.”

BMI

Your body-mass index, or BMI, represents your height and weight. It’s your obesity level.

“As your weight increases, so does your resting heart rate — which makes sense, of course, because there’s more tissue to support, and the heart needs to work harder,” notes Emir-Farinas.

But the Fitbit data also shows an association between high RHR and low body weight.

“Yeah, there’s an optimal BMI, where the body is able to work efficiently. Either side of that, the body isn’t at an optimal state of general maintenance and efficiency. It’s having to work harder to provide the basic provisions.”

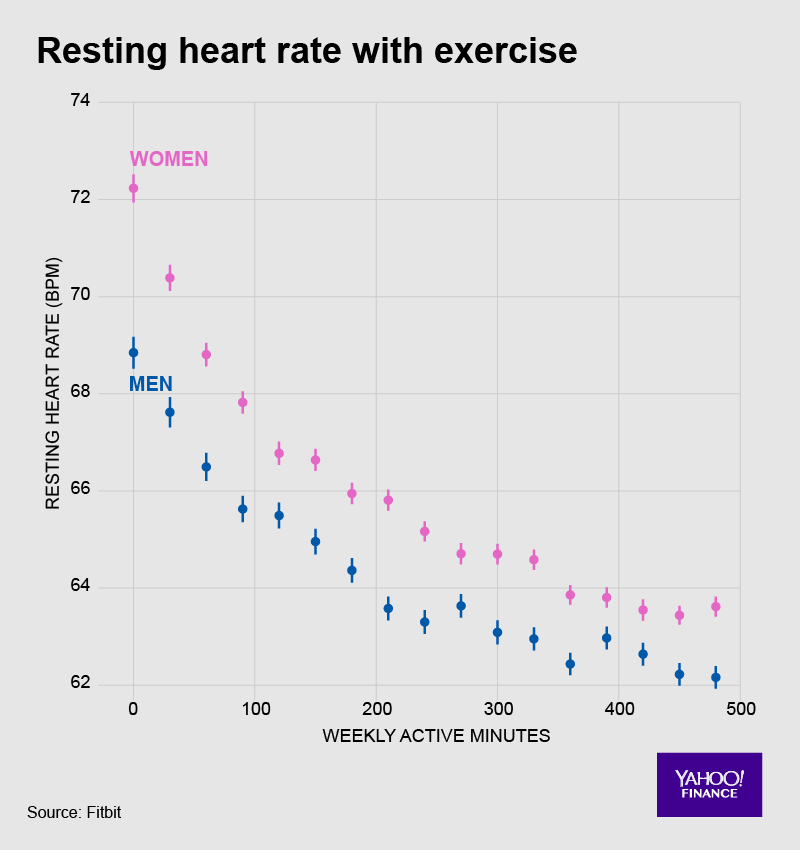

Physical Activity: Quantity

It’s not news that getting exercise is good for your heart. (The American Heart Association recommends that adults get 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous active minutes a week.)

What is surprising, though, is that the benefit tapers off after a couple hundred minutes of exercise.

“That’s good news — you don’t have to work out every minute of every day to continue to get more benefit,” says McLean. “After 200 to 300 minutes per week, you don’t see much of a change in resting heart rate or a benefit. I don’t have to do 500 minutes, I can do half that. That’s achievable.”

Physical activity: Consistency

Fitbit’s data makes it clear that it’s not just about getting a lot of exercise — it’s getting it consistently. The more consistent you are, the lower your resting heart rate.

Sitting all week and then blowing yourself out on the weekend is not a great approach. “You can’t gain cardiovascular health from a once-a-week exercise bash. Running in the morning and then sitting all day — that’s not a great approach, either,” Emir-Farinas says.

This, of course, is why smartwatches and fitness bands today all pop up reminders once an hour to get up and walk around.

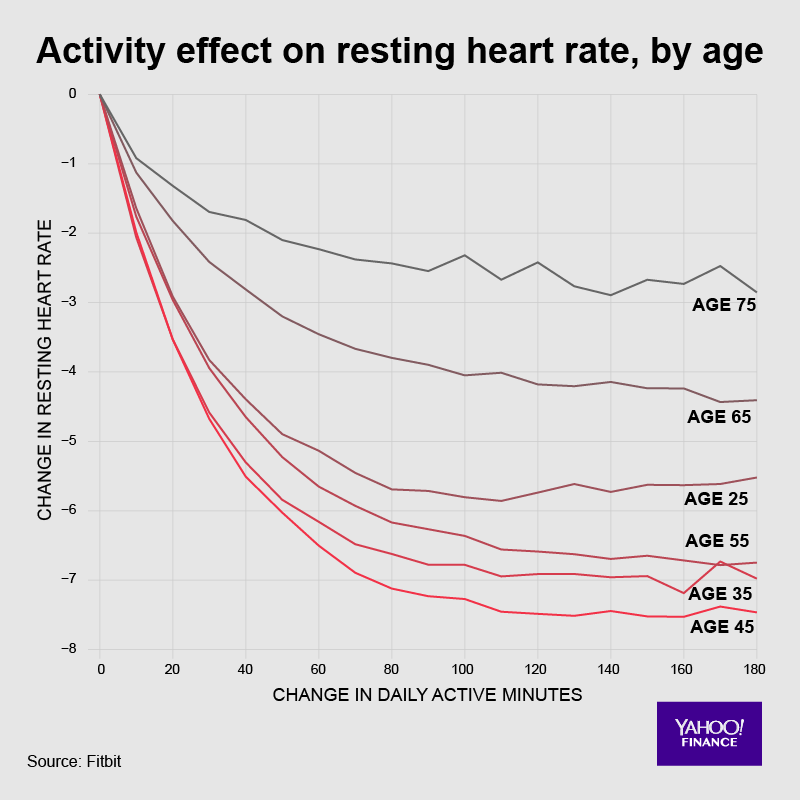

RHR and age

The next chart emphasizes that it’s possible to lower your heart rate at any age.

“As you can see, younger individuals can achieve a larger decline than older individuals,” says Emir-Farinas. “But it is possible for older people to reduce their resting heart rate, too, with sustained physical activity.”

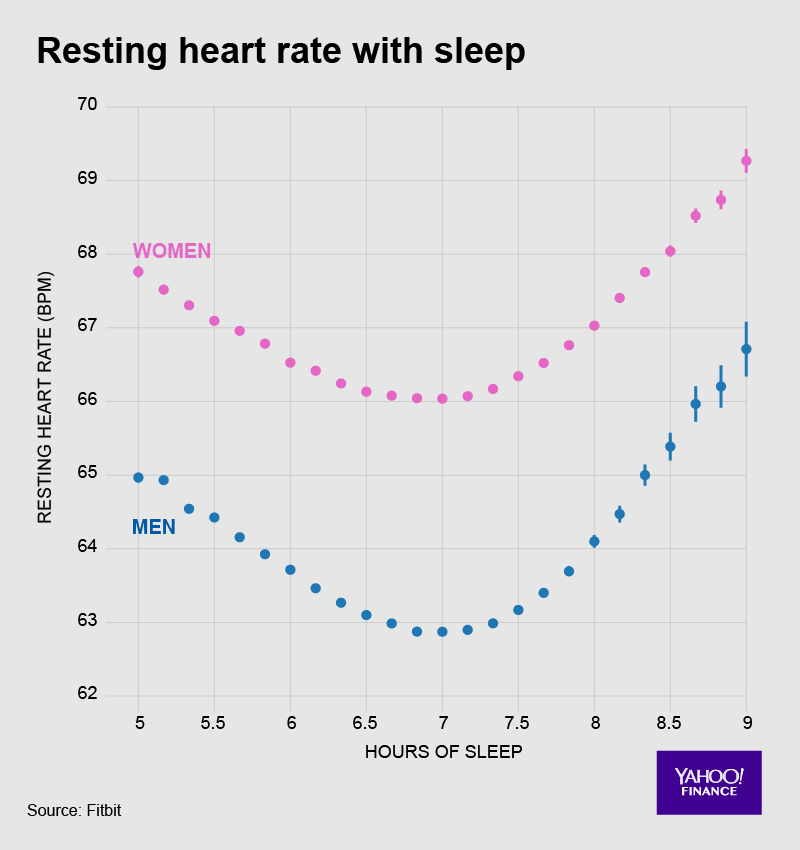

Sleep

Sleeping is good for you — but only to a point. Too much sleep might actually be bad for you.

“There is a sweet spot,” says Emir-Farinas. “It’s very clear from this plot that you have this window of optimal sleep, and it really does have an impact on your resting heart rate.”

That sweet spot is not 8 hours of sleep a night — it’s 7.25 hours. In terms of heart health, that’s the number you should be going for. “Which is good news for busy people,” says McLean.

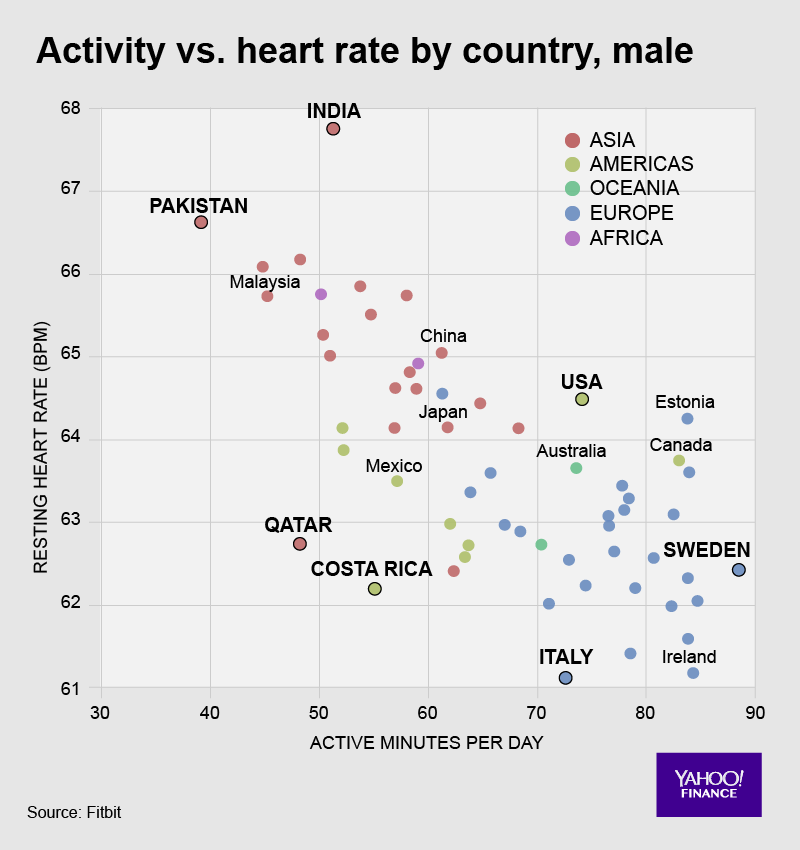

Country vs. Country

“These are my favorite charts,” says Emir-Farinas. She plotted age-adjusted data from the 55 countries with the most Fitbit wearers.

It graphs the citizens’ activity levels (horizontal axis) against their average resting heart rate (vertical).

The variation in heart rates is, to me, just crazy. Among people who get about 55 minutes of activity a day, the RHR is about 62 beats a minute in Costa Rica, but almost 70 in India! What could that mean?

“That means there’s other factors at play,” Emir-Farinas says. “It’s their nutrition, it’s their BMIs, it’s their practices, medication — and genetics, of course. That’s also a big part of it.”

In general, Europe beats the world here. “They have designed their cities so that there will be more physical activity. People have to walk more just do normal activities: going to the grocery store, going to work, they have to walk a little,” she says. (Check out Sweden, for example: almost 90 minutes of activity a day!)

They also drink a lot of wine in Europe. Just sayin’.

The scientists note that Qatar seems to be an outlier. Seventy percent of the Qatari population is obese — yet their RHR is an impressive 62. How could that be?

Emir-Farinas’s theory is that huge numbers of them are on blood-pressure and heart meds.

Congratulations to Italians, by the way, with an impressive 84 minutes a day of activity, and a nearly-dead 61 beats-a-minute RHR.

And as for Pakistan, with the worst activity level and a sky-high RHR — get with it, people!

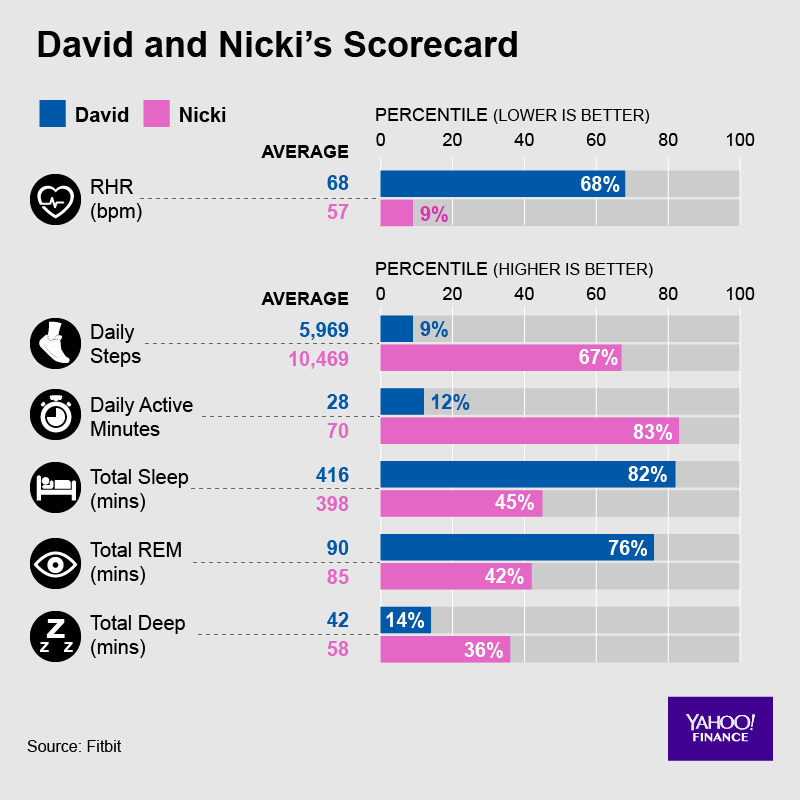

Nicki and David

My wife Nicki has run 16 marathons. The last time she ingested fat or sugar, she was probably in kindergarten. She’s going to live to be 200.

So I wasn’t entirely looking forward to the slide that compares her health to mine. (I have run 0 marathons.)

Sure enough: There she is, in the ninth percentile of resting heart-rate. Meaning that 91% of women her age have a higher heart rate.

“Her resting heart rate is very low for her age and gender group. Daily active minutes — it’s amazing, 70 minutes per day,” says Emir-Farinas.

I was horrified to discover my Daily Active Minutes stat: I’m in the 12th percentile. (In my defense, these numbers don’t include all the sedentary people who don’t wear fitness bands.)

But Emir-Farinas cheered me up: “On the other hand, your sleep is amazing. You’re smashing it with your REM duration.”

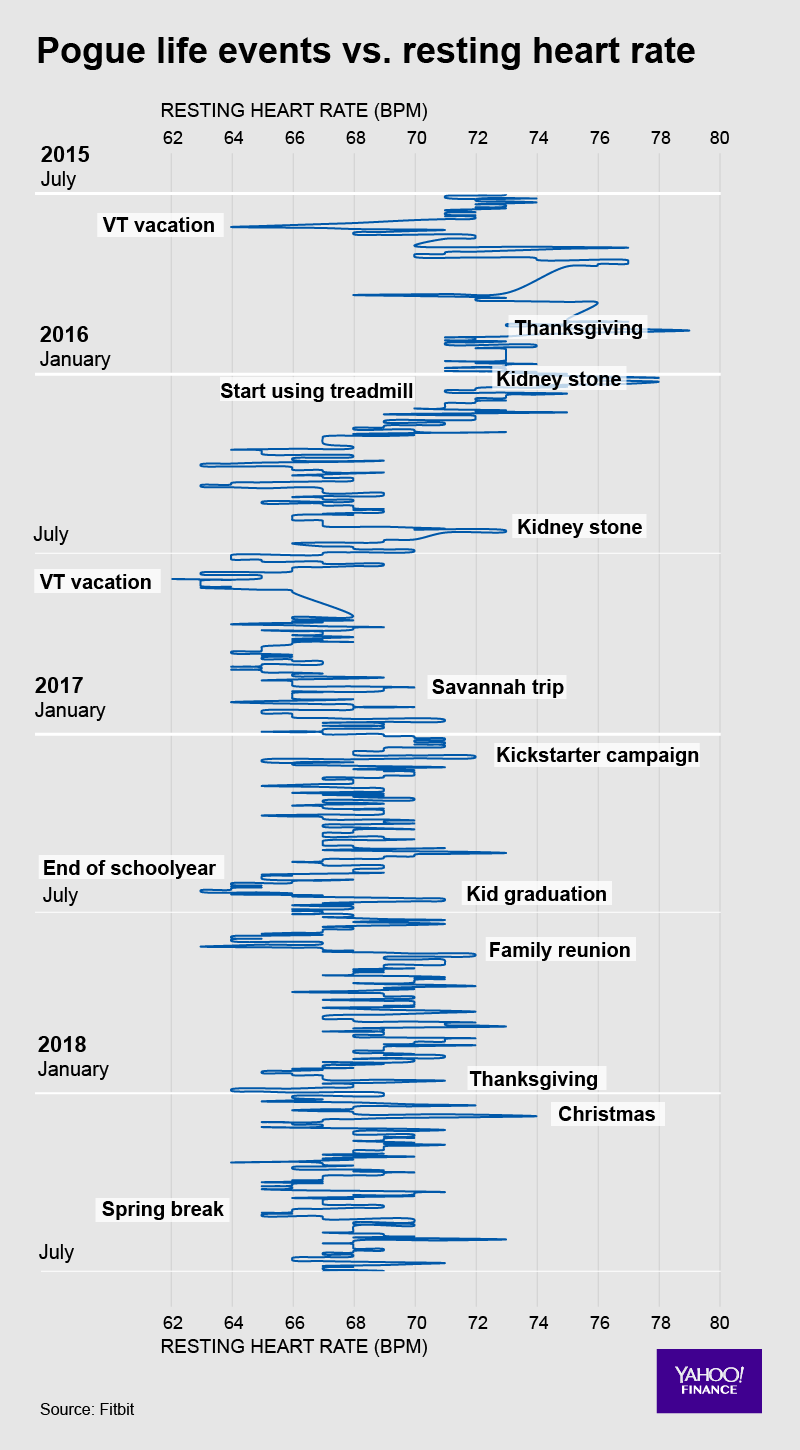

The journal study

The wildest slides, for me, were the ones where they plotted our life events against our heart-rate data. Here’s mine:

Kind of wild to see how starting to use a treadmill — the first regular cardio workouts I’ve ever really gotten — visibly lowered my entire heart-rate range.

Also, it turns out that having kidney stones is bad for you. My heart rate went through the roof both times.

I was surprised and amused, though, to see the second most stressful events on my graph: holiday get-togethers.

“You see the heart rate go up before your family reunions, and then tend to really take a long time to come back after it,” notes McLean. In other words — who knew?? — holidays with the family are not a guarantee of peace, relaxation, and joy.

“You heard that first at Fitbit,” jokes Mclean.

The takeaways

Your resting heart rate boils a whole range of health-related stats — exercise, diet, age, sleep, where you live — down to a single, reliable statistic.

“Your resting heart rate is a very easily understood and digestible metric,” says McLean. “It’s something that lets you say, ‘Wow, I see my resting heart rate — I see it changing, that means something.’ It’s so motivational. I can go, ‘Wow, these are the things that obviously worked for me and these are the things that aren’t.”

He hopes to spread the word about the resting heart rate beyond the community of hard-core athletes.

“We view everyone as an athlete,” he says. “So you can be 20, you can be 30, you can be 40, you can be 70. You’re your own athlete, and you have an opportunity to improve your health.”

David Pogue, tech columnist for Yahoo Finance, welcomes comments below. On the web, he’s davidpogue.com. On Twitter, he’s @pogue. On email, he’s poguester@yahoo.com. You can sign up to get his stuff by email, here.

More by David Pogue: