Campaign books that help shatter our politics

In the beginning there was Theodore White, the legendary observer of 20th century presidential campaigns, with his “Making of the President 1960.” Then there was Joe McGinniss’ brilliant account of the first iteration of modern campaign consulting, “The Selling of the President,” and Hunter S. Thompson’s dystopian companion piece, “Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72.” Many years later, Richard Ben Cramer wrote “What It Takes,” the “Ulysses” of campaign chronicles.

As I write these words, I glance up to scan these and other titles, their well-worn spines poking out from my shelves like the face of a literary Rushmore. For generations of readers, they humanized our politics even as they demystified it.

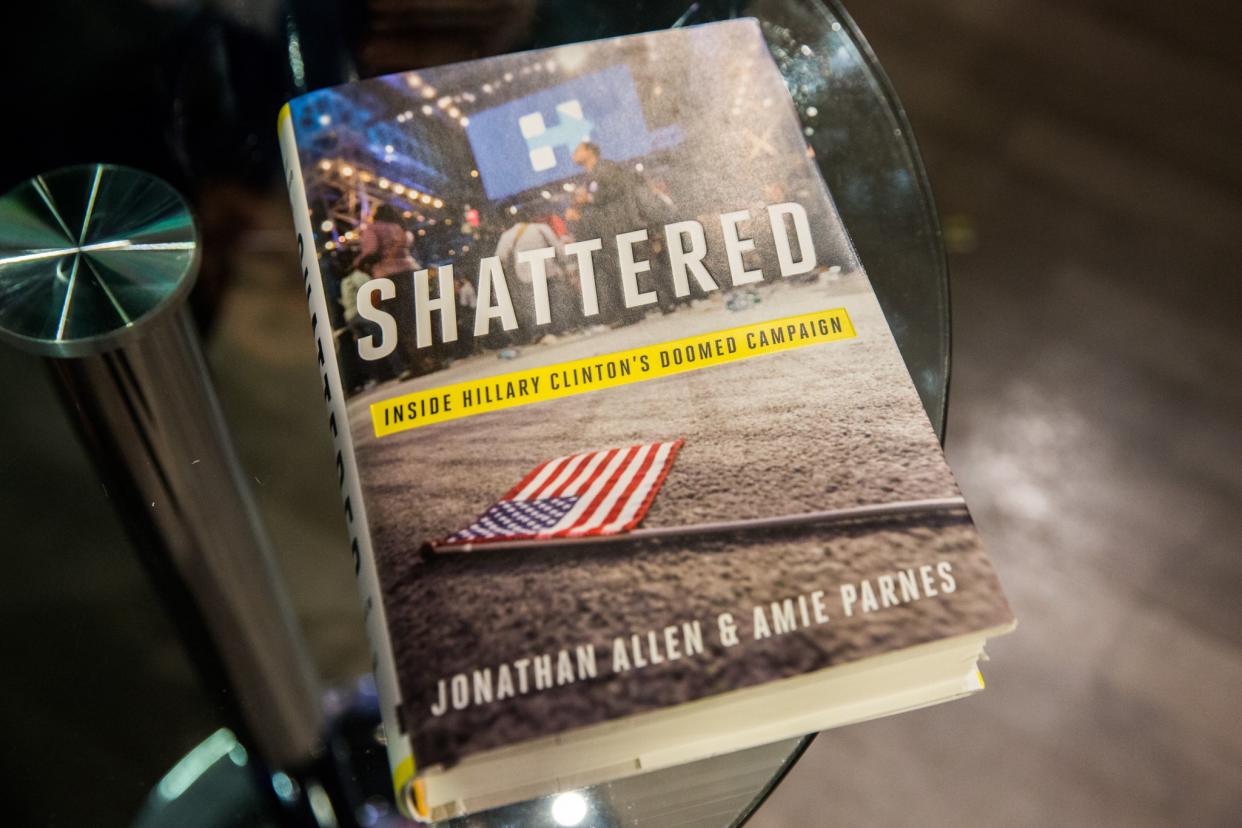

Not so much today, in the age of “Game Change” and “Double Down” and whatever the upcoming installment in the series will be called — maybe “Winning Bigly” or some other cliché that won’t outlive the moment. This week, Washington is amusing itself with “nuggets” from a book called “Shattered: Inside Hillary Clinton’s Doomed Campaign,” which managed to beat its competitors to the virtual shelves of your Kindle.

(How I despise that word: “nuggets.” Almost as much as I hate the words “juicy” and “buzzy.” If I were an unelected czar, like Jared Kushner, I’d issue an edict saying that anyone using the term “buzzy” without irony could be beaten senseless with his own keyboard, the assailant subject only to a minor fine.)

I don’t know the authors of “Shattered,” Jonathan Allen and Amie Parnes, but they seem like capable and energetic reporters. There’s no lack of industry in the breezy book they apparently wrote in less time than it takes me to finish reading one.

No, my problem is with the entire genre of contemporary campaign books, which don’t illuminate the soullessness of our political culture so much as they reflect it.

You can’t really treat presidential politics as a form of shallow entertainment and then claim to be shocked when a shallow entertainer wins the presidency.

I get why today’s political writers would want to emulate the books a lot of us grew up reading, the ones that made covering campaigns seem noble and glamorous. I get why book publishers will still lay out sizable advances for them, since politics has never been an easier sell than it is now among the subset of passionate readers who follow Politico in the same way that some of us refresh ESPN 20 times a day.

But you can’t actually write the books that a McGinniss or a Cramer wrote now, even if you have half their talent. That’s because, to quote “Hamilton,” those guys were in the room where it happened. They were witnesses to history, at a time when history hadn’t yet conspired to lock them out.

I once worked for a magazine called Newsweek (go ask your parents), which every four years, at monumental expense, sent a reporter to embed himself or herself in every major presidential campaign, solely for the purpose of publishing a comprehensive, behind-the-scenes book when it was over. More often than not, those reporters built real trust and saw things the rest of us couldn’t have.

There’s no trust anymore — largely, as I’ve written at great length, because our industry almost overnight became more predatory and less thoughtful. And so today’s campaign chroniclers are left to “reconstruct” events after the fact, eagerly inviting operatives to share endless anecdotes that burnish their own images while tearing down everyone else.

All of which seems to edify the new breed of campaign reporter, who finds nothing so newsworthy as the arcane tactics and rivalries that have attended every campaign since ancient Greece. You know: nuggets.

So here’s what you’ll learn, apparently, from reading “Shattered.” A lot of people thought the campaign manager wasn’t good at his job. An accomplished speechwriter joined the campaign, but then he grew irritated and quit. Bill Clinton says things that aren’t always in good taste.

Also, the candidate mismanaged aspects of her campaign, and she got frustrated a lot, and sometimes yelled. She didn’t love being criticized, either.

Well, OK. I’m not saying there aren’t some aspects of a compelling narrative there, which is the same way I feel when I turn on the TV and “The Voice” is on. But toward what end, exactly? What light does it cast on the things that actually matter?

Books like this one may not create the manifest dysfunction in our politics and our political journalism, but they certainly don’t help, either.

They make our most serious politicians even more remote and unreachable, opening the door wider for self-interested dilettantes. What person of gravity wants to spend time with reporters who seem only to be fixated on the atmospherics and personality clashes of a campaign, when any word spoken in candor is likely to become a “nugget,” void of context or compassion?

And the hoopla around these books sends a signal to ordinary Americans that we in the media don’t care about the same things they care about. Maybe we don’t.

If you read through the publicity surrounding “Shattered,” it’s hard not to conclude that we’re endlessly and breathlessly obsessed with who decided to spend the ad dollars in which market, and with how the campaign was organized on a flow chart, and with whether the candidate polled as likable or not. (Hint: not really.)

Lord knows I’ve written my share over the years about the tradecraft that underlies campaigns. I wrote around 16,000 words in the New York Times Magazine about Ohio’s turnout operations in 2004, back when “ground game” was still more of a football term than a political one.

But I’d like to think I never confused all the tactical stuff with the deeper questions that make campaigns matter, like how you find an answer for global markets, or how you manage a wildfire of technological change.

The best campaign books of an earlier era captured the political moment in a way that reflected the upheaval happening everywhere else in the culture. Today’s imitators somehow manage to do the reverse; they grab a screenshot of political minutiae that seems to exist in isolation, as if it were totally disconnected from deeper trends in the society.

More than any of this, though, the problem with the “Shattered” genre is that it treats politics, principally, as celebrity-driven drama. These books are the Us Weeklys of political history, rich with characters and intrigue and climactic moments, perfectly calibrated for bidding wars over the made-for-TV movie options, but barren of any deeper insight or meaning.

And the bottom line is this: We in political journalism can’t very well go around decrying the triumph of entertainment over substance without taking responsibility for our role in making it plausible. We can’t scoff at the reality TV takeover of our campaigns while celebrating coverage that reads like nothing so much as the recap of a season finale.

We’re at a pivotal moment in journalism, when we’re being asked to defend our values and our relevance and our depth. It’s a moment for which the Washington Post has offered up a grim new slogan: “Democracy dies in darkness.”

It can die in a hail of nuggets, too.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: