The world needs to look at Britain to understand global wage growth fragility

After years of stagnation, global wage growth is finally beginning to accelerate.

It’s a big deal because seeing any kind of meaningful wage growth has felt like a phenomenon that would never happen as countries like the UK and US have seen unemployment rates tumble without salaries growing at the same rate.

However, as analysts at Nomura pointed out, global wage growth is speeding up and “nowhere has this been seen as clearly as in the UK.”

Nomura analysts say in a recent research note that economic recovery is now 10 years old and labour markets have tightened significantly and now, “thanks to a combination of cyclical and structural factors,” countries are experiencing wage inflation.

Effectively, “a combination of trade protectionism, falling working age populations and general de-globalisation trends may be raising the cost of labour and should continue to do so in coming years. Trend productivity growth should also positively influence real wage growth.” They added that economic recovery and resulting tighter labour markets and the rising consumer price inflation “look to be finally seeping into wage growth.”

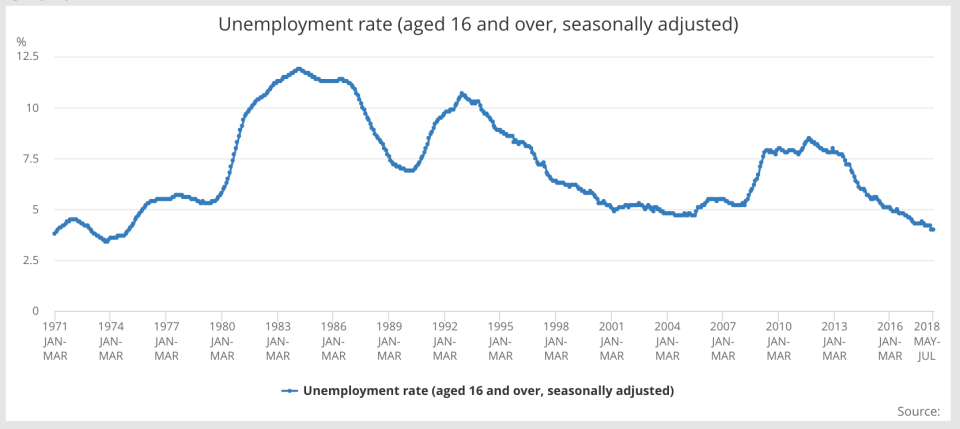

The UK is a major example of this. Unemployment rates are at their lowest level since the first-half of the 1970s at 4%.

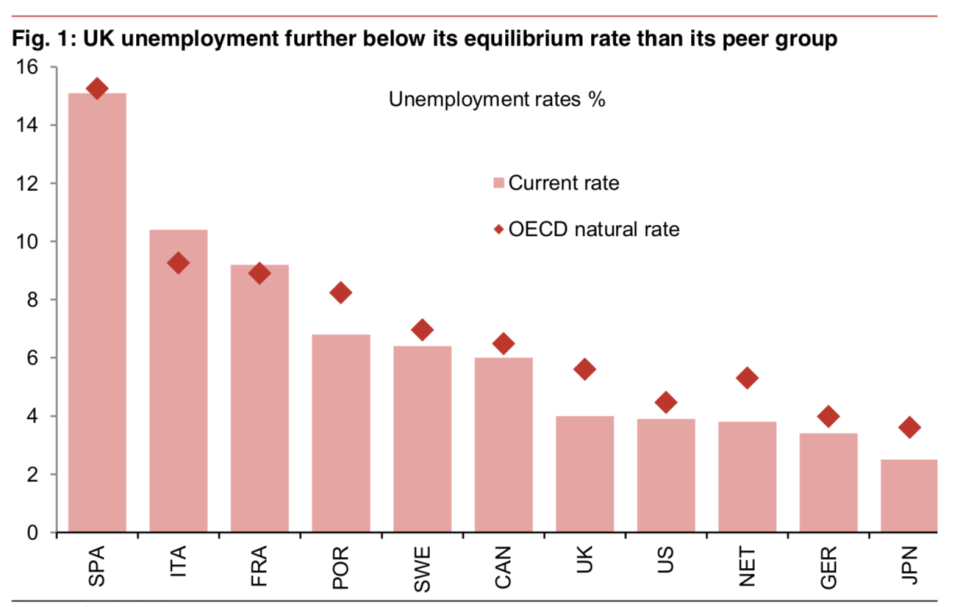

In the UK “the unemployment rate has fallen more notably below its equilibrium level and job switching has become prevalent as households have become more confident about their employment prospects,” they said.

However, the analysts warn that in the UK, reflected globally, “wage growth is recovering from a prolonged period of weakness — real wages, in level terms, are still lower than they were a decade ago.”

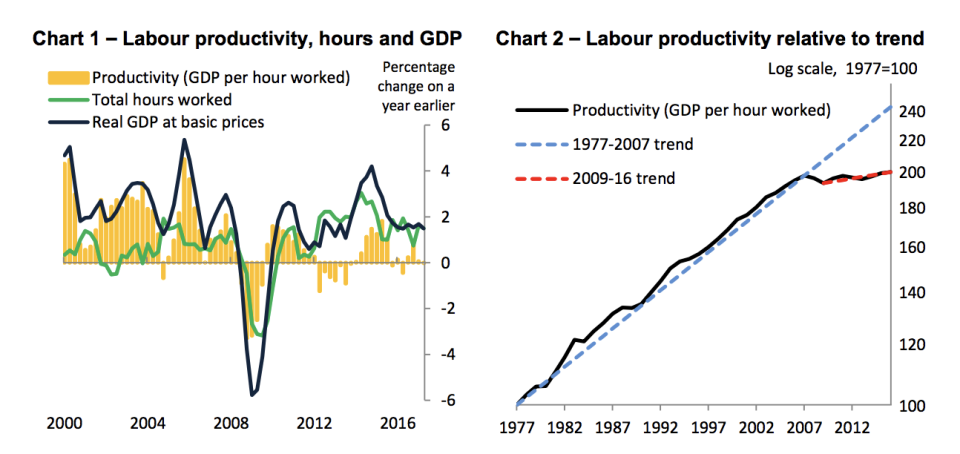

On top of that, the productivity puzzle still continues. Productivity has been measured in different ways but it’s largely viewed as the total value added of the UK economy divided by the total number of hours worked — how much an average worker in the UK economy produces each hour.

As the Bank of England has pointed out in speeches and a report, productivity has yet to recover to levels from before the credit crisis. This is despite more people than ever in the UK having a job.

It’s for this reason that Nomura analysts warn as well that meaningful wage growth could halt if slow productivity growth persists.

“Then not only would that likely constrain pay growth, but may also mean the central bank ends up raising interest rates when rates of pay growth are slower than typically was the case during past monetary tightening cycles,” they said.

“As a result, we may not need to see wage growth pick up any more than it has already in order to justify further rate policy tightening, even if rate rises end up being ‘limited’ and ‘gradual’ in the Bank of England’s own terminology.”

Global economies are still facing headwinds, including the need for greater productivity, that could alter wage growth.

On Monday (8 October), St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank president James Bullard said in a speech that the US “will likely need faster productivity growth in order to maintain current real GDP growth rates.” He added that higher labour productivity growth would raise the US potential growth rate to 3.4%.

Meanwhile, the International Monetary Fund just downgraded its forecast for global growth. It now expects the global economy to expand by 3.7% in 2018 — a 0.2 percentage point downward revision — thanks to mounting concerns of “further negative shocks.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance