Why a bigger Powerball jackpot is actually the worst time to buy a ticket

The Powerball lottery jackpot is swelling to $750 million and people are lining up to buy tickets before Wednesday night’s drawing.

Is that a good idea? Math says no.

Crunching historical lottery data reveals that buying a lottery ticket when the jackpot is at newsworthy amounts is not a smart move, partly due to an often-overlooked factor: the odds of having to split the jackpot.

Gamblers and mathematicians look at ‘expected value’

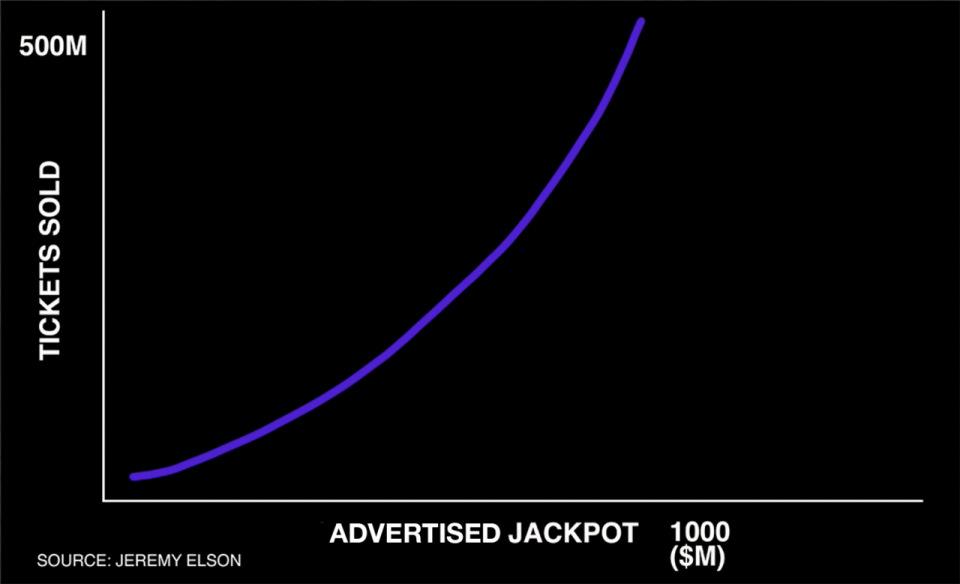

When the jackpot grows to a noteworthy size, ticket sales tend to increase exponentially — a phenomenon well documented by computer scientist Jeremy Elson. As more and more people buy tickets, the probability of seeing the jackpot split among multiple winners also grows. And that can have a huge factor on the overall expected value of any given lottery ticket.

When gamblers and statisticians weigh whether or not a bet is worth the gamble, they look at what’s called expected value. In a simple bet, it’s usually calculated by multiplying the probability of winning a bet by the payout. For example, the expected value of a $1 payout on a heads-up coin flip would be calculated as .50 times $1, or 50 cents.

So a rational gambler would be willing to bet up to 50 cents for a gamble with those parameters. Gambling more than 50 cents would be a losing proposition, over time.

Of course, when it comes to the lottery, the odds of winning are a lot worse than a coin flip. The probability of winning a Powerball jackpot is roughly 1 in 292 million, compared with about 1 in 303 million for Mega Millions. That probability is constant no matter how many tickets are sold, as are the adjustments that need to be made to account for taxes and converting the advertised annuity jackpot to a lump-sum dollar amount.

‘Must-play’ events are everything but that

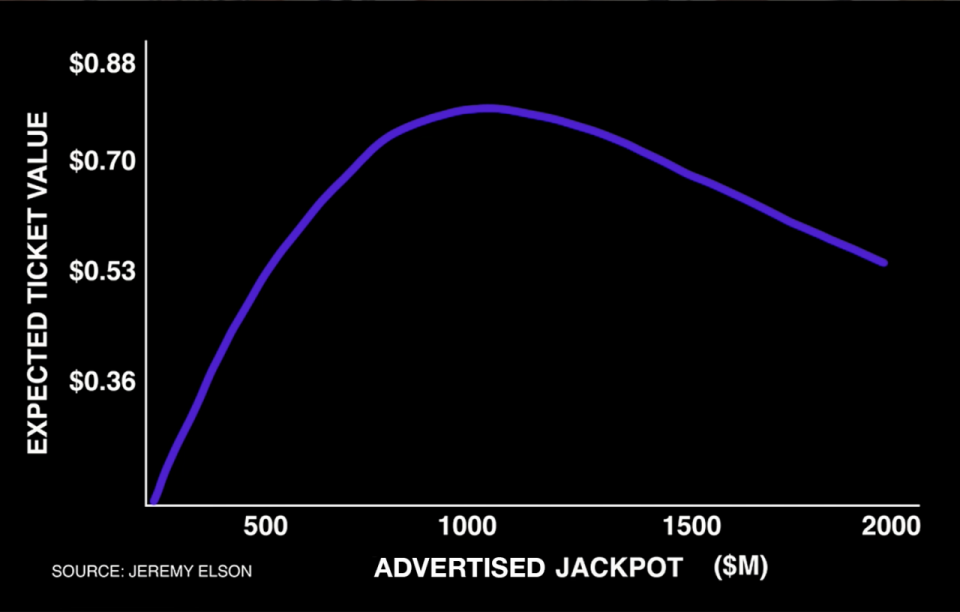

And the fact that the probability of splitting a jackpot hinges on how many tickets are sold means that the expected value of a lottery ticket tends to decline as jackpots approach record amounts.

In fact, according to Elson, the expected value for lottery tickets tend to peak when jackpots hit large amounts — just not so large that they become “must-play” events.

That being said, people generally don’t buy a lottery ticket based on expected values, seeing as the $2 cost of a lottery ticket is almost always more than the expected value (the house basically always wins). But that does beg the question: Why, then, are millions of people buying tickets?

Behavioral economists generally echo the establishment work from researchers Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who originally pointed out that humans have a tendency to overestimate low-probability events, such as the roughly 1 in 300 million odds of hitting a lottery jackpot.

Zack Guzman is the host of YFi PM as well as a senior writer and on-air reporter covering entrepreneurship, startups, and breaking news at Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter @zGuz.

Read more:

Blue Moon's creator launched a cannabis beer that sold out in 4 hours

Exclusive: Canopy Growth to invest up to $500 million in hemp production in U.S. states