Legendary Facebook backer nails the existential issue facing social media

As a veteran tech investor and early social media adopter, Roger McNamee is uniquely positioned to explain why Facebook and Google are so successful — as well as how “we are drowning in evidence that there are costs that society may not be able to afford.”

McNamee’s new essay in Washington Monthly, “How to Fix Facebook — Before It Fixes Us,” deftly details social media’s profound impacts on Brexit, the 2016 U.S. election, the news media and, ultimately, all users.

By explaining how social media has been “exploited by a hostile power to drive people apart, undermine democracy, and create misery,” McNamee is attempting to “trigger a national conversation about the role of internet platform monopolies in our society, economy, and politics.”

‘Being used in ways that the founders did not intend’

In 2006, McNamee persuaded 22-year-old Mark Zuckerberg not to sell Facebook to Yahoo for $1 billion.

“I was convinced that Mark had created a game-changing platform that would eventually be bigger than Google was at the time,” McNamee writes. “Facebook wasn’t the first social network, but it was the first to combine true identity with scalable technology.”

McNamee became a Facebook power user by creating a page to market his band in 2007 and building it into one of the highest-engaging fan pages on the ever-changing platform.

“My familiarity with building organic engagement put me in a position to notice that something strange was going on in February 2016,” he writes. “The Democratic primary was getting underway in New Hampshire, and I started to notice a flood of viciously misogynistic anti-Clinton memes originating from Facebook groups supporting Bernie Sanders.

“I knew how to build engagement organically on Facebook. This was not organic. It appeared to be well organized, with an advertising budget. But surely the Sanders campaign wasn’t stupid enough to be pushing the memes themselves. I didn’t know what was going on, but I worried that Facebook was being used in ways that the founders did not intend.”

McNamee studied the phenomenon in the run-up to the June 2016 Brexit vote, a situation where “one side’s message was perfect for the algorithms and the other’s wasn’t,” he writes. “The ‘Leave’ campaign made an absurd promise — there would be savings from leaving the European Union that would fund a big improvement in the National Health System — while also exploiting xenophobia by casting Brexit as the best way to protect English culture and jobs from immigrants. It was too-good-to-be-true nonsense mixed with fearmongering.”

And then came Russia’s multipronged influence operation on the U.S. general election, which involved leveraging Facebook to great effect.

‘Why pay a newspaper?’

McNamee details how smartphones “turned media into a battle to hold users’ attention as long as possible. And it left Facebook and Google with a prohibitive advantage over traditional media.”

He rhetorically asks, “Why pay a newspaper in the hopes of catching the attention of a certain portion of its audience, when you can pay Facebook to reach exactly those people and no one else?”

In addition to battling declining ad revenues, the American press found itself competing in a free-for-all information landscape. When WikiLeaks took its trove of hacked Democratic emails and published them in a searchable online database, outlets covered the fresh material. The U.S. intelligence community said Kremlin-backed hackers stole those emails, meaning the press indirectly became an unwitting tool of Russian election-meddling after WikiLeaks laundered them into the public sphere.

The starkest example occurred in October 2016, during the run-up to the U.S. election, as WikiLeaks strategically leaked Clinton campaign chair John Podesta’s stolen emails.

Content based on the curated emails — created by mainstream news outlets as well as agenda-driven pages arising out of thin air — rocketed around Facebook, which had become the world’s most prolific provider of news. (From July 2015 until June 2017, Facebook consistently drove more traffic to publishers than Google.)

The Podesta leaks and the resulting coverage made WikiLeaks a top topic on Facebook and Instagram. The impact was particularly striking among older men, a demographic that votes at a rate around 70 percent. After the election, Washington Post reporter Dave Weigel noted the mainstream media’s role.

Tough for the press to admit, but in 10 years we’ll generally agree that it got played by foreign agents who wanted to sabotage Clinton.

— Dave Weigel (@daveweigel) November 14, 2016

Beyond amplifying any misjudgments by the press, social media also provides a seemingly endless platform for fake information published by anyone. Some of those fake posts go viral, suggesting that many people passed on the false content without properly vetting it (or not caring that it’s fake).

“40,100 retweets of a quote tweet of a news article link that doesn’t exist, from an account with 80 followers,” the popular information security account @SwiftOnSecurity said about on one such post. “Consider how much of the world narrative you [ingest] and accept from passing glance alone.”

40,100 retweets of a quote tweet of a news article link that doesn’t exist, from an account with 80 followers.

Consider how much of the world narrative you injest and accept from passing glance alone. pic.twitter.com/wDeVewirVC— . (@SwiftOnSecurity) January 8, 2018

@SwiftOnSecurity continued: “Consider how often the asymmetry of human timescale and effort needed to individually evaluate information is exploited against you. … 106,000 ‘likes’ of an article that does not exist.”

‘Only the people we want to see it, see it’

It wasn’t only the Russian government that leveraged Facebook during the U.S. election. The Trump campaign executed a massive paid media strategy that involved paying nearly $6 million to Cambridge Analytica, a micro-targeting firm created by enigmatic billionaire Robert Mercer, and spent roughly $70 million on Facebook. And unlike Hillary Clinton’s campaign, the Trump team eagerly embraced the opportunity to work alongside embeds from Facebook, Twitter, and Google to optimize engagement.

After Trump’s victory, Cambridge Analytica claimed to be “instrumental in identifying supporters, persuading undecided voters, and driving turnout to the polls.” The Trump campaign attempted to distance itself from the firm after reports that Cambridge Analytica’s CEO had reached out to WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in an attempt to obtain hacked emails from Clinton’s private server (though it’s unclear whether the WikiLeaks founder possessed them).

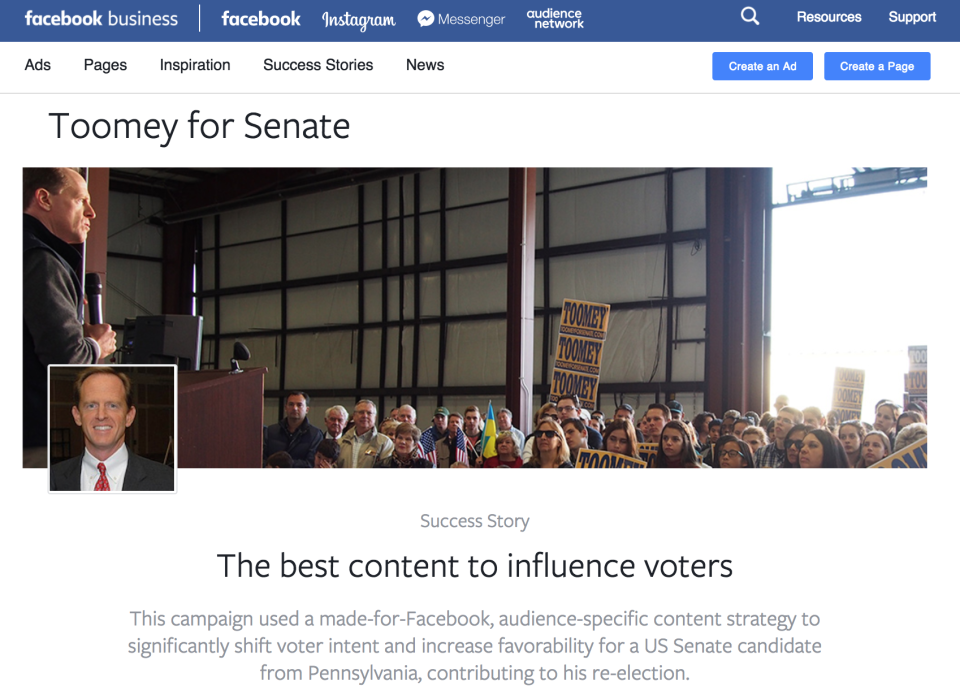

Social media ad platforms changed the game for political campaigns seeking to deliver messages to specific groups of voters. Facebook has even published success stories of how U.S. politicians swayed the vote using its ad platform.

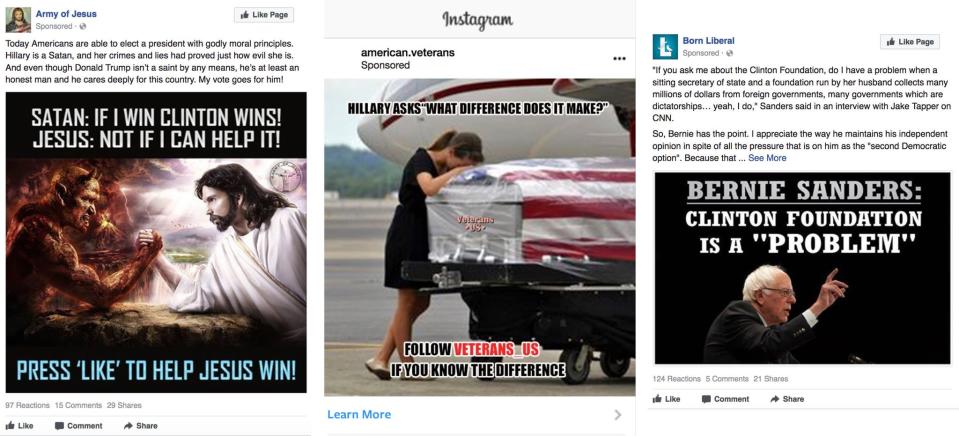

Creating effective ad campaigns on Facebook has become something of a dark art. At one point, the Trump campaign created an anti-Clinton animation based on a 1996 remark she made about some African-American gang members being “super-predators.” The primary goal was to depress Clinton’s vote total by delivering the content to certain African-American voters through Facebook’s advertising system of nonpublic “dark” posts.

Brad Parscale, the digital media director for Trump 2016, told Bloomberg Businessweek that dark posts allowed for a situation where “only the people we want to see it, see it.”

‘Trolls and bots impersonating Americans’

In July 2017, McNamee and former Google design ethicist Tristan Harris met with two members of Congress. They explained to the lawmakers how Russia had attempted to use social media to influence the American electorate.

“We theorized that the Russians had identified a set of users susceptible to its message, used Facebook’s advertising tools to identify users with similar profiles, and used ads to persuade those people to join groups dedicated to controversial issues,” McNamee writes. “Facebook’s algorithms would have favored Trump’s crude message and the anti-Clinton conspiracy theories that thrilled his supporters, with the likely consequence that Trump and his backers paid less than Clinton for Facebook advertising per person reached.”

Social media researcher Jonathan Albright defined the effect as “cultural hacking,” telling the New York Times that the Russians “are using systems that were already set up by these platforms to increase engagement. They’re feeding outrage — and it’s easy to do, because outrage and emotion is how people share.”

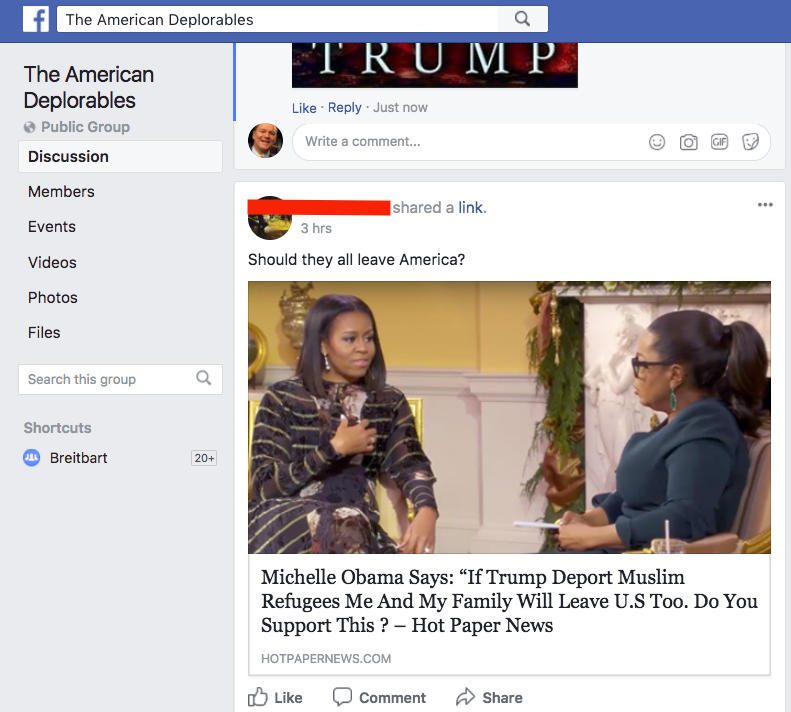

McNamee further notes that “once users were in groups, the Russians could have used fake American troll accounts and computerized ‘bots’ to share incendiary messages and organize events. Trolls and bots impersonating Americans would have created the illusion of greater support for radical ideas than actually existed. Real users ‘like’ posts shared by trolls and bots and share them on their own news feeds, so that small investments in advertising and memes posted to Facebook groups would reach tens of millions of people.”

Up to 126 million users on Facebook alone

One Kremlin-linked troll farm, the Internet Research Agency, published 80,000 posts and spent about $100,000 on 3,000 ads to deliver divisive content to an estimated 29 million Facebook users between January 2015 and August 2017. Overall, Albright’s research suggested, Facebook posts by 470 pages publicly linked to Russia’s effort were shared hundreds of millions (and potentially billions) of times.

Whether the Russian influence operation on Facebook had an effect on American voting choices is still up for debate. What’s clear, however, is that a U.S. adversary successfully manipulated the platform in an attempt to pollute the minds of many voting-eligible Americans.

Some Russian-backed pages even attempted to organize dozens of politically charged events, a few of which were attended by Americans. In May 2016, Russian trolls managed to create dueling anti-Islam and pro-Islam protests at a religious center in Houston.

Evidence of Russian meddling on Facebook. (Image: U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee)

“The objective of influence is to create behavior change,” former FBI agent Clint Watts told the Daily Beast. “The simplest behavior is to have someone disseminate propaganda that Russia created and seeded. The second part of behavior influence is when you can get people to physically do something.”

In the end, the Times reported, the biggest social media companies estimated that “Russian agents intending to sow discord among American citizens disseminated inflammatory posts that reached 126 million users on Facebook [and another 20 million on Instagram], published more than 131,000 messages on Twitter and uploaded over 1,000 videos to Google’s YouTube service.”

‘They will be manipulated again’

McNamee concludes that “Facebook, Google, Twitter, and other platforms were manipulated by the Russians to shift outcomes in Brexit and the U.S. presidential election, and unless major changes are made, they will be manipulated again.”

His suggestions for action include social media companies directly reaching out to users exposed to Kremlin-generated content (using a tactic taken from deprogramming cult members); congressional testimony by the CEOs of Facebook, Google, Twitter; aggressively banning digital bots that impersonate humans; increased transparency from platforms; prevention of commercial exploitation of consumer data; and further regulations related to antitrust law being applied to Facebook and Google.

McNamee acknowledges that societal problems arising from social media are daunting but says “that’s no excuse for inaction. There’s far too much at stake.”

Read the entire 6,700-word essay at Washington Monthly >

This post has been updated.