With Kavanaugh confirmed, a bloc of conservative justices may set the Supreme Court's agenda

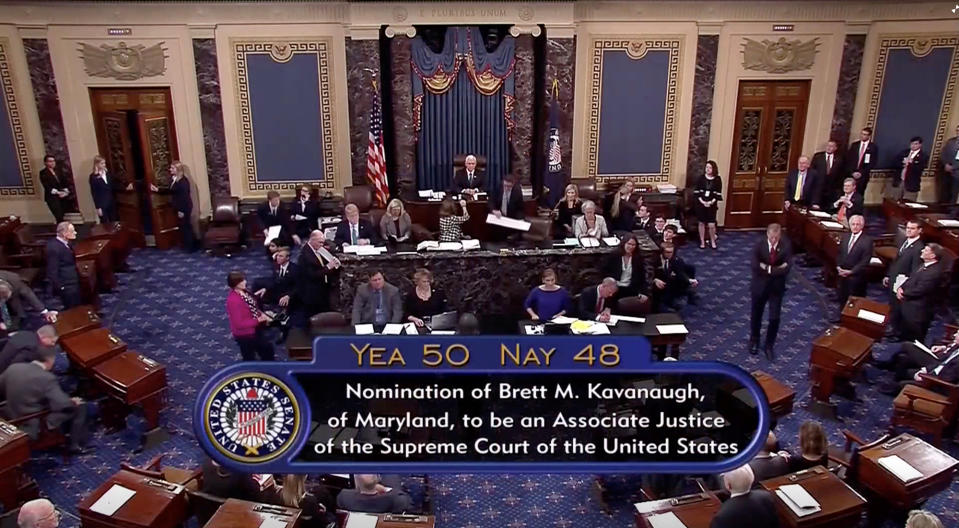

On Saturday afternoon, as women bellowed objections from the Senate galleries and other protesters chanted slogans and listened to speeches in front of the Supreme Court, senators confirmed Brett M. Kavanaugh to a lifetime appointment to the United States Supreme Court by a vote of 50-48.

Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, the lone Republican opposed to Kavanaugh’s confirmation, voted present as a courtesy to Sen. Steve Daines, R-Mont., who favored Kavanaugh but was away from the Senate for his daughter’s wedding. Kavanaugh is the second Supreme Court justice appointed by President Trump. The vote at the end of a relatively untroubled Saturday of mild protests and senatorial speeches marked an anticlimax for a political drama that has riveted the nation for weeks and may have a few surprises yet to come.

Kavanaugh will take over Justice Anthony Kennedy’s swing seat as soon as Tuesday morning. Observers will be watching to see if the court’s five-justice majority sets out on a radical project to refashion American law in accordance with the conservative movement’s desires, or whether one of those five justices takes on the role of checking those ambitions and steering the Court on a more moderate path.

If any of the court’s conservatives step into the swing voter role, observers almost unanimously agree it will likely be Chief Justice Roberts. Roberts, however, has been a fairly reliable conservative vote during his 13 years on the bench, tending to break with Republicans only rarely, in cases where the Court’s legitimacy is at stake — such as the bitter partisan battle over the Affordable Care Act. The question of the years to come is whether that tendency will expand on account of the court’s new realities.

Unlike Justice Kennedy, Kavanaugh has a reputation as a hardline conservative partisan. Many of the Senators voting against Kavanaugh’s confirmation cited the partisan sentiments expressed in his opening statement at last Thursday’s hearing to consider Christine Blasey Ford’s allegations that Kavanaugh sexually assaulted her at a high school party in early 1980s. In that prepared statement, Kavanaugh blamed Democrats for allowing Ford’s allegations to come to light and appeared to promise revenge against them if he were confirmed to the bench.

Early in his career, Kavanaugh served in roles more partisan than a typical nominee to the court. In addition to more traditional clerkships and a stint at the Solicitor General’s Office, Kavanaugh worked as a prosecutor in Kenneth Starr’s investigation of President Bill Clinton, making a reputation for himself as one of the most aggressive prosecutors in a famously unsparing operation pursuing the Monica Lewinsky scandal. He also got involved in the recount fight on George W. Bush’s side in the disputed 2000 presidential election. Kavanaugh went on to serve in the Bush White House, first in the counsel’s office and then as staff secretary, managing judicial nominations and other hot-button issues in the fraught years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. This work remained shrouded in some mystery even on the day of his confirmation vote.

President Bush nominated Kavanaugh for a seat on the D.C. Circuit in 2003, but Democratic senators who accused him of being too partisan stalled his confirmation for three years.

“Some might call Mr. Kavanaugh the Zelig of young Republican lawyers,” Sen. Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., said at his initial confirmation hearing in 2004. “He has managed to find himself at the center of so many high-profile, controversial issues in his short career, from the notorious Starr Report to the Florida recount, to this president’s secrecy and privilege claims, to post-9/11 legislative battles, including the victims compensation fund, to controversial judicial nominations.”

Because of his partisan track record prior to his time on the bench, his 12 years of uniformly conservative decisions at the D.C. Circuit, and the conservative leanings of the four other Republican-appointed justices, Kavanaugh’s ascension to the Supreme Court has been widely expected to mark the end of a dynamic that has helped to determine the court’s decisions for roughly 47 years. While justices appointed by Republican presidents have for many decades constituted the majority of the Court, several of those Justices, including Anthony M. Kennedy and Sandra Day O’Connor, did not hold to a doctrinaire Republican ideology and were considered swing votes.

Kennedy, who is retiring and whose seat Kavanaugh is taking, originally appointed by President Ronald Reagan, was widely considered the court’s last remaining swing vote. While Kennedy reliably voted with the conservatives on many issues, he habitually broke with them on issues of individual rights, voting in a sometimes uneasy alliance with the liberal justices on social issues like marriage equality and reproductive rights. Kennedy is the author of Obergefell v. Hodges, the court’s landmark decision establishing a right to same-sex marriage. Kennedy himself replaced Justice Lewis F. Powell, also a Republican-appointed swing justice.

At Justice Powell’s retirement, President Reagan had sought to move the court to the right by appointing a firebrand conservative judge from the D.C. Circuit, Robert Bork. The failure of Bork’s nomination paved the way for the more heterodox Anthony Kennedy.

Kavanaugh himself did little to dispel expectations that he would follow a conservative line in his confirmation hearings. He signaled in a number of ways that he intends to chip away at access to abortion. He took a hard line on guns. He refused to provide any comfort that he would uphold the law against denying health insurance coverage on account of preexisting conditions. He outlined and expansive vision of executive power that would limit the ability of other branches of government to constrain or investigate the president and his associates.

With Kavanaugh stepping in for Kennedy, the court appears likely to have five reliably conservative votes on most issues. The person who is likely to determine whether this majority will embark on a broad reevaluation of the Court’s decisions or hew to its swing-vote dominated recent past is Chief Justice John Roberts. In his 13 years on the bench, the chief justice has not fit the mold of a Kennedy or Powell, but he is the most centrist of the five. Observers predict that Kavanaugh’s confirmation will lead to a large volume of so-called test cases reaching the court; test cases are lawsuits identified and advanced through the appellate courts by activists (conservative activists, in this case) because they feature an issue on which the activists want the law to change. A similar dynamic may play out with litigation around the Mueller investigation, with interested parties like Andrew Miller, the Roger Stone associate who is resisting a grand jury subpoena, appealing cases to the Supreme Court to see if the justices will apply a broader vision of executive power than they have in the past.

The votes of only four justices are necessary to grant a case the opportunity to be heard by the Justices, so Kavanaugh and his three highly conservative colleagues, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Clarence Thomas, have the power to put a test case on the Supreme Court’s agenda. Once a test case is before the court, Roberts will have to decide whether to reshape the law according to the conservatives’ desires or to transition into the role of a swing justice, something he has occasionally done to uphold parts of the Affordable Care Act. Soon, Roberts may have to decide whether he will play a similar role on questions of executive power, setting up a direct confrontation with the president, particularly if the questions concern the special counsel investigation into Trump’s possible ties to Russian interference in the 2016 election.

Kavanaugh’s raucous confirmation process became, in some ways, a microcosm of Trump’s presidency. The policy implications were largely secondary to a dizzying array of controversies piled up faster than the body politic could digest. Trouble started from the first day, with Kavanaugh’s widely lampooned praise of President Trump. “No president has ever consulted more widely, or talked with more people from more backgrounds, to seek input about a Supreme Court nomination,” the freshly minted nominee told the president in the East Room of the White House.

From there, the issues multiplied. Washington Post reporters looking into Kavanaugh’s large, fluctuating credit card debt reported that the White House had attributed it to a seemingly improbable tale about baseball tickets (a White House official would later say this initial report was misleading).

Republicans and Democrats on Capitol Hill began to fight about the release of documents from Kavanaugh’s time in the White House, with Republicans settling on a highly restricted and accelerated document production that may have left some lurking time bombs in the government’s files.

When hearings kicked off, the controversies continued. Kavanaugh refused to shake the hand of a man whose daughter had been murdered in the Parkland shootings in Florida. He appeared to trip up over questions from Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., about whether he’d discussed the special counsel’s Russia investigation with anyone from the president’s law firm. And documents initially marked confidential showed that he’d played a more significant role in a Senate hacking scandal and the confirmation of certain controversial judicial nominees than he had let on in past sworn testimony to the Senate.

Finally, after the initial hearings concluded, Christine Blasey Ford and Deborah Ramirez came forward to accuse Kavanaugh of sexual assault, and a third woman accused Kavanaugh of crude behavior in a lurid sworn affidavit. Ford’s allegations led to an extraordinary additional hearing before the Senate judiciary committee and a controversial supplemental FBI investigation.

But in the end, none of the controversies, not even the blockbuster sexual misconduct allegations that came to light at the end of the confirmation process, could halt Kavanaugh’s momentum and the determination of the Senate’s Republican majority to put him on the bench for life and start an uncertain new chapter in the court’s history.

Although the vote was anticlimactic, a few thousand protesters gathered outside the Capitol building and — a few hours before the final vote — crossed police lines to rally on the steps of the U.S. Senate, prompting mass arrests.

The protest rally then moved to the steps of the Supreme Court, just a few hundred yards away, where members of the Senate addressed the crowd.

“This is not defeat. This is the beginning of a revolution in this country,” said Sen. Ed Markey, D-Mass.. He added moments later that he was calling for “a revolution at the ballot box.”

Inside the chamber, protests continued during the vote to confirm Kavanaugh. Vice President Mike Pence presided over the Senate, providing the insurance of an extra Republican vote if needed, and he warned spectators in the gallery not to interrupt.

But as soon as the vote was called, about a dozen protesters — most of them women — stood and voiced their opposition. “I am a patriot. I do not consent,” one woman yelled. She screamed loudly as she was taken by Capitol police out of the chamber and down the hall.

Protesters interrupted the vote several more times, specifically targeting lawmakers who had cast the deciding votes in favor of Kavanaugh after struggling with whether they should do so.

“You’re a coward, Flake,” one young man yelled at Sen. Jeff Flake, R-Ariz., who a week ago, bucked his own party to call for a one-week delay to allow for an FBI investigation into Ford’s allegations of sexual assault.

When Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., voted in favor of the nomination, a young woman stood and yelled out, “I am a survivor of sexual assault. How dare you try to save your own seat?”

There was another outburst when Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, voted aye. Collins was essentially the deciding vote for Kavanaugh.

Pence issued a few warnings to the gallery, the last coming just before the Senate clerk announced the final vote of 50-48. When Pence announced that Kavanaugh’s nomination had been officially confirmed and approved by the Senate, a top aide to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., pumped his fist and walked out the door.

And another round of protests erupted in the gallery. “This is a stain on American history. Do you understand that?” a woman stood and yelled before being apprehended by police.

Outside the Capitol, protesters yelled “Shame!” at Pence’s motorcade as he departed.

More Yahoo News stories on the Supreme Court:

‘Things happened in the 80s’: Women Trump fans explain their faith in Brett Kavanaugh

Brett Kavanaugh’s ex-boss: There’s no basis to demand his recusal from Mueller cases

Confusion, chaos hit Capitol Hill in wake of FBI report on Kavanaugh

Yahoo News explains: Who is allowed to see the Kavanaugh FBI report?

Lawsuits point to large trove of unreleased Kavanaugh White House documents