Brexit and Trump's trade war are not enough to bring about the end of globalisation

World trade has enjoyed 70 years of boom. But when Britain voted to leave the European Union with no set plan on how to do that and US president Donald Trump started following through on protectionist trade proposals, many analysts warned that this was the beginning of the end of globalisation.

However, economists Ric Deverell and Hayden Skilling from financial firm Macquarie say that even though “the Trump trade war is likely to be disruptive” and “even the most extreme threats” will unlikely cause a spike in global trade tariffs, last seen pre-1950.

“Over recent years, the concept of ‘globalisation’ has come under pressure, with the UK vote to leave the European Union, and the election of President Trump often portrayed as clear evidence that the halcyon days of global integration are over,” they say in a note to clients.

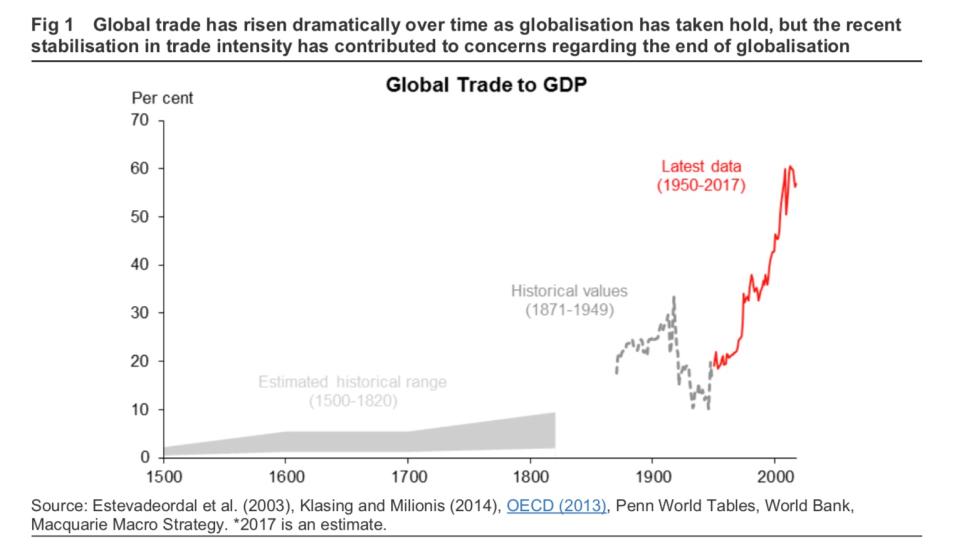

“While there is little doubt that the dramatic increase in the trade intensity of the global economy has stalled—the ratio of trade to GDP has flat-lined since the ‘Great Recession’—it is notable that we remain dramatically more integrated than at any other time in human history, with global trade in 2017 around 60% of global GDP, up from around 6% in 1820.”

‘America First’

Ever since Trump entered the White House, he has been slapping tariffs on goods from China and the EU in a bid to enact his raft of protectionist trade measures, under his political branding of “America First.”

Now the president has threatened to smack tariffs on more than $200bn worth of Chinese goods. His administration has already implemented duties on $34bn worth of imports, and there will be an additional $16bn placed on Chinese goods on 23 August. This has, of course, sparked a trade war as China, the world’s second largest economy behind the US, will not take this lying down. The country’s Ministry of Commerce has been clear that it will retaliate by imposing its own tariffs on US goods.

On top of that, Trump has tried to take on the EU, which is made up of 28 member countries until Britain leaves on 29 March 2019. After the White House administration threatened to impose a 25% tariff on European autos, a key industry for the bloc’s biggest economy Germany, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker seemed to get Trump to put a freeze on an all-out trade war.

“We agreed today, first of all, to work together toward zero tariffs, zero non-tariff barriers and zero subsidies on non-auto industrial goods,” Trump said. “We will not go against the spirit of this agreement unless either party terminates the negotiation,” he said. “So, we’re starting the negotiation right now but we know very much where it’s going.”

While this seems like a pertinent staving off of a trade war, it should be noted that this is just putting a tariff slap frenzy on pause. The risk of returning to retaliatory levies is still very much there.

Can’t live, with or without EU

Meanwhile, the world is awaiting what will happen when Britain leaves the EU.

There has not been a solid plan ever since Britain voted to leave the EU on 23 June 2016. Over the last two years, the UK government has gone back and forth on what they envisage Brexit to look like, all the while having significantly different implications to how trade between the bloc and the UK would look like.

There are only two real scenarios in the event of Brexit—a “soft Brexit” and a “hard Brexit”, also known as a no-deal Brexit.

A soft Brexit is pretty much what Britain has now except a seat at the decision-making table – unified tariffs, same free migration rules to live and work, and common laws. This is the markets preferred option as it keeps Britain within favourable trading and working conditions with the bloc. About 43% of UK exports in goods and services go to EU member states and 54% of imports to the UK come from countries in the bloc.

A hard Brexit would be like walking over a cliff-edge as there would be no deal in place when it comes to tariffs, rules on free movement, which is one of the prerequisite of being part of the EU, as well as unified regulations that allows the goods and services to seamlessly being bought and sold across EU country borders. The hit on the economy has been predicted to be vast by many and therefore would trickle down and hit the pockets of the person on the street.

But while Brexit and the increase in protectionism emanating from the US are undoubtedly huge headaches for various economies, the Macquarie economists say “they are unlikely to spark a sharp reversal of the centuries-long trend towards increasing global interconnectedness.”

“Indeed, increased global trade over time has been driven by a range of factors, most of which will remain largely unaffected by recent economic and policy developments,” they add.