What’s next for Marco Rubio?

MIAMI — The big question facing Marco Rubio is not what he does next but how he chooses to do it, based on the lessons he draws from his defeat.

Rubio, whose U.S. Senate term ends in January and whose bid for the White House splintered on the shoals of his home state Tuesday night, could run for Florida governor in 2018. He could leave politics for a time, go into business and make some money, or start a nonprofit and then run for president again in 2020. But it is hard for many to see him fading altogether from the political scene.

“It is not God’s plan that I be president in 2016, or maybe ever,” Rubio said in his concession speech here Tuesday night. His use of the word “maybe” was a clear indication that, already, 2020 is on his mind.

Assuming his time in public life is not at an end, the dilemma facing the 44-year-old, still-baby-faced politician is who he chooses to become after his bruising experience in the time of Trump.

Does he retain the hopeful, optimistic tone and message that facilitated his rise to national office in 2010? Or does he try to somehow chase the worship of celebrity and the rage in the electorate that has been exposed, and encouraged, by Republican frontrunner Donald Trump?

“I do worry that he learns the wrong lessons from this cycle, and thinks he lost because he wasn’t angry or insane enough,” said Steve Schale, a top Democratic operative in Florida who has admired Rubio’s political skills as a member of the opposition party.

“If he learns the wrong lessons, he’ll go off and do crazy, insane things for the next few years, and that won’t end well,” Schale said.

Schale’s advice could be self-serving — he’s close to one Democrat who may run for governor herself in 2018, Rep. Gwen Graham — but his recommendation for Rubio would be to not run in 2018, and to go into business instead.

“Go keep your head down and do something outside of politics,” Schale said. “In the modern world, you don’t need a political platform to succeed in politics. He’s a young and talented guy, and success in the real world would allow him to mount a comeback at almost any time.”

There is some logic to that argument. Certainly in this election, any whiff of time spent in elected office has been politically poisonous. Trump had nearly universal name ID with the electorate due to his years in reality TV and before that, from his life as a New York businessman who dabbled in the world of sports entertainment.

Marco Rubio announces the suspension of his campaign during a rally in Miami on Tuesday. (Photo: Carlo Allegri/Reuters)

Slideshow: March 15 presidential primaries >>>

Trump has made a career of courting controversy. Rubio, if he wanted, could dive headfirst into the world of celebrity. That is the route to take if the lesson of 2016 is that the best route to political success is to copy the Trump model — that all publicity is good publicity, shame is passé, and thinking through how you might govern before you rouse passions is for losers.

Of course, it’s possible Rubio already learned his lesson about attempting this, having tried to beat Trump at his own insult game in the last month, only to overstep and have it backfire.

Another interpretation of Rubio’s humiliation is that voters just decided he needed to slow down and grow up a little, or maybe more than a little. He’s been in a hurry his entire adult life, and his impatience to get to the next level of political power has led Rubio to leave friends and allies in the dust. Many of the pre-defeat obituaries on Rubio’s career during the last week suggested that he had forgotten where he came from.

“I don’t think the lesson here is that he wasn’t Donald Trump,” said Alex Castellanos, a Cuban-born Republican operative who has advised numerous presidential candidates. “The lesson for him is, one, that it wasn’t his time. And that in an uncertain moment, people wanted strength and experience.

“If he goes out into the real world and enjoys business success or becomes governor and actually runs something, that would position him for success,” said Castellanos.

Rubio was told by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and by 2008 GOP nominee Sen. John McCain to wait his turn. And Rubio mocked that advice often on the campaign trail.

“This is not a time for waiting,” Rubio said. He continued to ridicule “elites” in his concession speech Tuesday.

“There are millions of people in this country that are tired of being looked down upon. Tired of being told by these self-proclaimed elitists that they don’t know what they are talking about and they need to instead listen to the so-called smart people,” Rubio said.

“I’ve battled my whole life against the so-called elites, the people who think that, you know, I needed to wait my turn or wait in line or it wasn’t our chance or wasn’t our time. So, I understand all of these frustrations,” he said.

But the voters spoke loud and clear. Out of 32 primaries and caucuses, Rubio won only three. And a longtime associate of Rubio’s said Tuesday as the polls were closing that there are some hard truths in that fact.

“He can’t try to please everyone,” said Al Cardenas, a longtime fixture in Florida Republican politics who brought a young Rubio into his law firm in the mid-’90s.

Cardenas pointed to the 2013 immigration fight as one of the most damaging periods in Rubio’s career, not because he backed a comprehensive bill, but because he cut and ran, leaving others in the lurch. As I wrote with Andrew Romano a year ago, Rubio panicked.

“He was a proud promoter of that bill. He enlisted myself and a number of other leaders to get behind him, put their political capital on the table,” Cardenas told me over a patchy phone line late Tuesday. “And you can’t just leave by yourself and leave everybody else behind and to their own devices.

“People don’t mind going down fighting, but they do mind going down fighting without the fellow who brought them to the dance to begin with,” Cardenas said.

Going forward, Cardenas said, Rubio “needs to stand his ground on issues of importance more often, although there is a short-term price to be paid.”

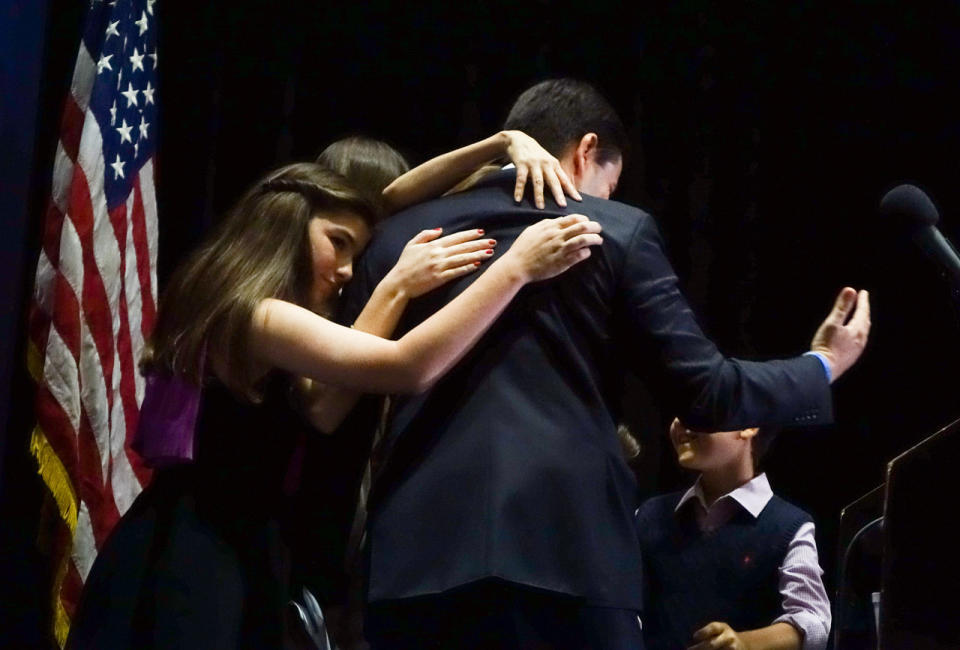

Rubio gets a hug from his family after a primary night rally Tuesday in Miami. (Photo: Angel Valentin/Getty Images)

In addition, Rubio developed a reputation over the years for giving short shrift to the hard work of legislating, another sign of his impatience. Cardenas also said this hurt Rubio’s ability to win over voters in his home state.

“He’s got to work harder at a larger group of dependable supporters on the electorate side, not just the donor base. That takes a lot of hard work, collegiality, and it takes showing up,” Cardenas said.

The challenge in all this for Rubio is that he has not settled on a political identity. He has dabbled here and flitted there, leaving voters with the impression he lacks a true center.

In his speech Tuesday, Rubio hit some of the notes that are part of his core message. At the heart of it was an attempt to give fuller voice to the frustrations of everyday Americans, but moving from that place of empathy to a place of hope.

“America is in the middle of a real political storm, a real tsunami. And, we should have seen this coming. Look, people are angry, and people are very frustrated,” he said.

“I know that we are living through this extraordinary economic transformation that is really disruptive in people’s lives. Machines are replacing them, their pay is not enough. I know it’s disruptive. But I also know this new economy has incredible opportunity,” he said.

Rubio seemed to sense that he had not worked hard enough to voice the frustrations of many American voters. Any politician who hopes to inspire anguished voters must first of all convince them that he understands them, and that he hears them.

His appeal to optimism summoned the nation’s history and heritage.

“We are the descendants of pilgrims. We are the descendants of settlers. We are the descendants of men and women that headed westward in the Great Plains not knowing what awaited them,” Rubio said. “We are the descendants of slaves who overcame that horrible institution to stake their claim in the American Dream. We are the descendants of immigrants and exiles who knew and believed that they were destined for more, and that there was only one place on Earth where that was possible.

“This is who we are, and let us fight to ensure that this is who we remain. For if we lose that about our country, we will still be rich and we will still be powerful, but we will no longer be special,” he said.

These were just the first soundings of any coherent message Rubio might attempt to reimagine.

Defeats and setbacks lead to times of reflection, and Rubio will now have plenty of time for that. He can use it to engage in political calculus and strategy. Or he can look inward, acknowledge his weaknesses as a candidate and as a person, and by so doing, begin the process of overcoming them.

At the conclusion of his speech Tuesday, Rubio said: “I will continue every single day to search for ways for me to repay some of this extraordinary debt that I owe this great country.”