The gatekeepers of a new Cuba

A house in Havana displays the flags of the United States and Cuba. (Photo: Orlando Barria/EPA)

Just moments before Air Force One touched down in Havana, a heavy rain arrived as well, dampening what was already a curiously subdued city.

Havana is normally an exuberant place. The day before, Cubans could be seen scrubbing their homes, painting storefronts and singing what is probably the country’s best-known song, “Guantanamera,” barely able to contain their excitement at the rapprochement between neighbors estranged for 57 years. Work crews were everywhere in the city, laying fresh asphalt on the potholed streets of Old Havana. One crew, manning a sputtering, apparently Soviet-built contraption for painting fresh white lines on the streets, burst into cheers as they passed the National Theater where President Obama will address the nation on Tuesday morning. Looking at the scrubbed and prepped streets, the new asphalt and trash-free gutters, one elderly woman noted, “Obama is the best mayor Havana ever had. He should come back every three months.”

But by the time Obama arrived on Sunday, the festive atmosphere was gone. Police inspectors visited guest houses popular with foreigners, urging the owners to be on the lookout for suspicious behavior, including anyone “inquiring about the economic situation, leaders or military objectives.” A rumor — one that proved to be false — spread among Cubans that much of the city would be shut down, keeping many people at home. Muscular men in guayabera shirts did appear in the afternoon at intersections near the ancient Cathedral Square in Old Havana, directing away traffic and pedestrians, leaving this boisterous core of Cuba’s tourism economy oddly empty as the fated hour approached.

A Cuban mother and son watch the TV broadcast of the arrival of the U.S. president and first lady at the José Martí airport on Sunday. (Photo: Desmond Boylan/AP)

Slideshow: Obama’s historic visit to Cuba >>>

The landing of Air Force One preempted all Cuban television shows, and Obama’s first appearance at the door of the plane raised a cheer that spilled out from living rooms into the streets. At dusk, in pouring rain that blotted out buildings across Havana Bay, the president visited the cobblestone square in front of Cuba’s landmark cathedral. Just minutes later, the tall figures of Michelle and Barack could be seen over the heads of their security at the adjacent Plaza de Armas, where they ducked back into a limousine, presumably as soaked as the small band of Cubans standing silently on the rain-lashed waterfront.

But the heavy rain and security dampened more than enthusiasm. The president faces sky-high expectations from both Cubans and Americans, expectations that will be difficult to meet. To do so, Obama and his American supporters will have to close the daunting gap between the hoped-for and the possible. They’ll need to know the gatekeepers of a new Cuban reality. Here are four people likely to shape the Cuban-American relationship for years to come.

Antonio Castro, son of Fidel Castro and vice president of the International Baseball Federation, in 2013, speaking about the Olympics that will be held in Buenos Aires. (Photo: Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images)

Antonio Castro, one of Fidel Castro’s five sons, is a doctor whose name seldom appears in Cuban media, but his title of physician for Cuba’s national baseball team masks his far more important role as an arbiter of what new policies would be acceptable to his father. He controls the baseball diplomacy, greenlighting the first exhibition game between the countries in 16 years, scheduled for Tuesday afternoon. He puts the imprimatur of the Castro name on negotiations over a legal route for Cuban ballplayers to reach the U.S., and for Major League Baseball to play, train and recruit in Cuba. (He is said to favor allowing ball players to move freely between the two nations, with a heavy tax on their MLB salaries.) Belying his title of team doctor, Tony Castro normally spends the entirety of important ballgames in the Cuban dugout and on his cellphone — leading to rumors that he is conveying play-by-play instructions from someone more powerful. Expect to see him Tuesday night, phone clamped to his ear, during the showdown between Cuba’s national squad and the Tampa Bay Rays.

Rosá Maria Payá, daughter of late Cuban dissident Oswaldo Paya, in 2013. (Photo: Ivan Franco/EPA)

Rosá Maria Payá, a charismatic young dissident, will be Obama’s primary contact with Cuban opposition figures. Daughter of the regime’s most dogged opponent, she believes (despite a lack of convincing evidence) that her father was murdered by the Castros in a staged car crash. Bitterly opposed to giving the dictator brothers any American help, she is likely to serve as a moral brake on American policy, and will be given a platform by Obama himself in a Tuesday meeting just before he leaves the island. Her “Cuba Decide” project aims to push both the Cuban and American governments to let ordinary islanders choose their future, rather than the unelected Castros. The White House has suggested that American companies coming to Cuba should offer high standards on labor practices and the right to unionize — demands that Payá may be in position to influence as a flag bearer among Cuban opposition figures.

Rodrigo Malmierca Diaz, Cuban minister of foreign trade and foreign investment. (Photo: Carlos Villalba/EPA)

The tall, glum-looking Rodrigo Malmierca Díaz is often seen standing only one or two steps from Raúl Castro, reflecting his vital portfolio as Cuba’s long-serving minister of foreign trade and foreign investment. His title links Cuba’s economic future to the tourist industry, the island’s largest source of foreign exchange by far. All hotel deals, cruise ship landings and other American investments must pass through his office for approval. Formerly the head of Gaviota, the Cuban military’s vast tourism company, he is said to favor deals with just a few high-profile American brands, including Starwood Hotels, American Airlines and Marriott. U.S. investment on the island will depend on his cautious embrace of a few American “test cases” on the island.

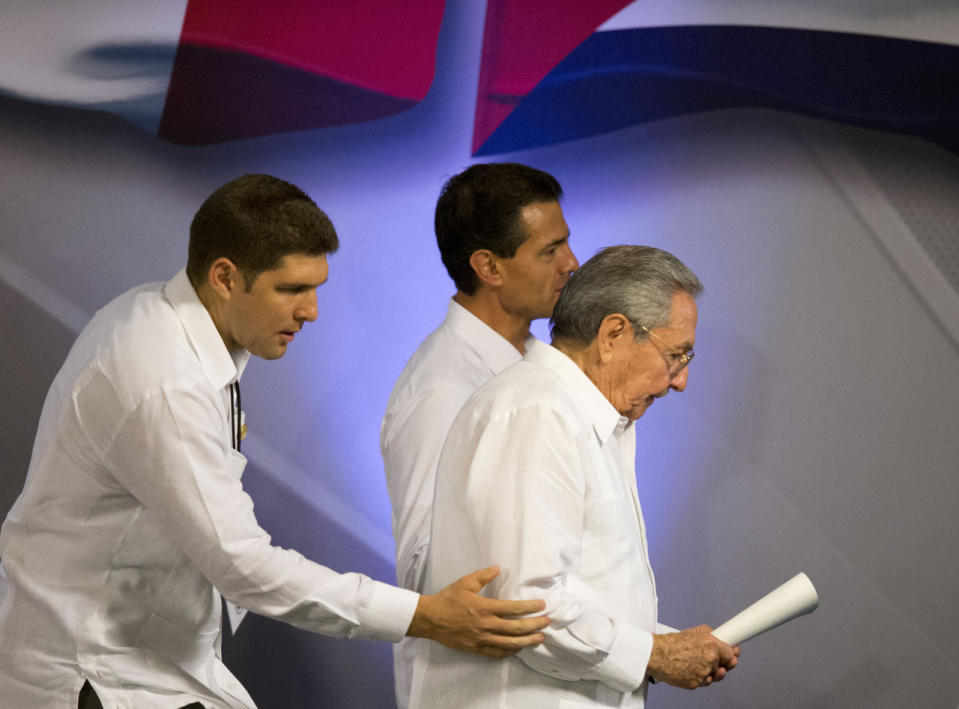

Raúl Rodriguez Castro, left, the personal assistant and grandson of Raúl Castro, reaches to guide his grandfather as he walks with Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto. (Photo: Rebecca Blackwell/AP)

Raúl Rodriguez Castro — known as “el Cangrejo,” or the Crab — is Raúl Castro’s grandson. Nominally a chief bodyguard for his grandfather, the bullet-headed Rodriguez Castro is a tough known for expelling critics from the country and edging awkwardly into photographs of his grandfather while they visit Paris or the U.N. — a sign of his ambition to be the revolution’s next-gen leader. His father, Luis Alberto Rodríguez López-Callejas, is a general who married into the ruling clan and controls the Cuban military’s business deals — an enormous and lucrative portfolio of hotels, bus companies, restaurants and even an airline. The Crab is the family insider most likely to get rich on new American business deals.