Is Ted Cruz ineligible for the presidency?

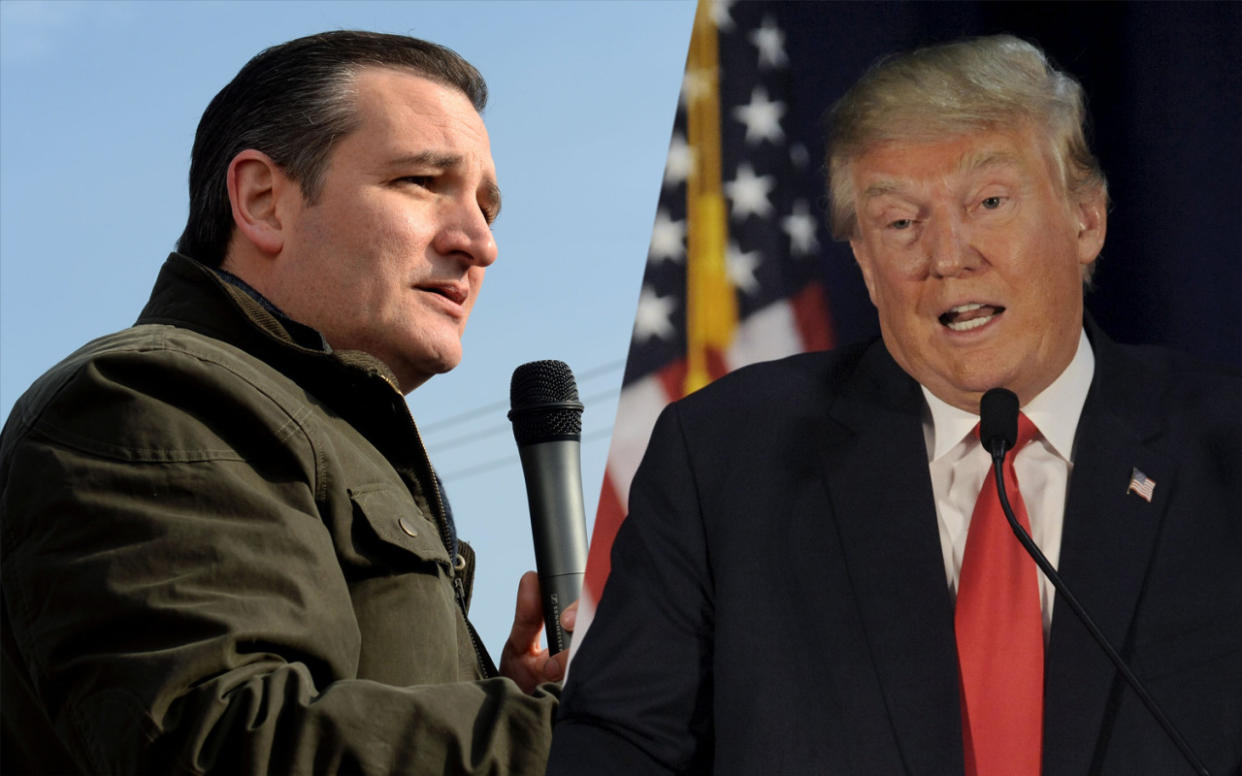

As the Iowa caucuses get closer, the fight between Republican presidential candidates Ted Cruz, R-Texas, and Donald Trump heats up. (Photo: Getty Images/Reuters)

As Ted Cruz overtook real estate mogul Donald Trump in Iowa polls earlier this month, his rival tossed a political bombshell at the Texas senator. He began questioning whether Cruz is eligible to be president at all, given that he was born in Canada.

“Republicans are going to have to ask themselves the question ‘Do we want a candidate who could be tied up in court for two years?’” Trump told the Washington Post. “That’d be a big problem.”

This attack on Cruz’s eligibility has already gained far more traction than Trump’s earlier foray into “birtherism,” questioning whether President Obama was born in the United States. Harvard law professor Larry Tribe wrote this week that it’s far from settled law whether his former student Cruz is eligible for the office he seeks and that the Supreme Court has never ruled directly on the matter. Tribe argues that by Cruz’s own conservative, originalist legal standards, he is not a “natural born citizen,” the requirement set forth in Article 2 of the Constitution.

That’s because in the late 1700s when the Founding Fathers wrote the Constitution, the notion of citizenship was mostly derived from English common law. Anyone born in a sovereign’s territory was subject to the king’s laws and protection. When the founders wrote that the president must be a “natural born citizen,” they were most likely resting on this definition. But the idea of inheriting citizenship from one’s parents no matter where one was born was already spreading. In fact, in 1790, the U.S. Congress passed a law stating that parents could pass on U.S. citizenship to their children born abroad.

Under our current laws, Cruz, who was born in Canada in 1970 to an American mother and a Cuban father, is unquestionably a U.S. citizen. What is less clear is whether he is “natural born” under Article 2 of the Constitution.

Some legal scholars believe a natural-born citizen is anyone who became a citizen at birth. Under that definition, Cruz qualifies. “I find Cruz’s political beliefs reprehensible, but I think it’s clear that he’s eligible to be president,” said Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California, Irvine, law school.

But others subscribe to the common-law definition, which would exclude Cruz. As Tribe points out, political preferences aside, more conservative justices who believe in hewing closely to the original meaning of the Constitution are likely to be tougher sells on Cruz’s eligibility than liberal jurists who see the Constitution as a living document.

The framers inserted the mysterious “natural born citizen” language into Article 2 “in an effort to prevent a British nobleman or foreign prince” from seizing control of the infant nation, write Sarah Helene Duggin and Mary Beth Collins in the Boston University Law Review. The idea was to prevent foreigners from stealing the republic’s presidency. They never defined exactly what the phrase meant, and nothing else in the Constitution gives any guidance as to how to interpret it.

The 14th Amendment, passed after the Civil War to ensure that freed black slaves became citizens, is the only part of the Constitution that addresses citizenship qualifications. It says that people born in the United States who are subject to its jurisdiction are U.S. citizens — leaving unanswered the question of whether citizens born abroad are “natural born.”

Congress and the states could clear the matter up with a constitutional amendment. Or the courts could weigh in and settle it, if someone sues over Cruz’s eligibility.

But it’s very unlikely that if Cruz were elected president in November, he would be thrown out as ineligible. The courts would most likely be reluctant to weigh in on such a divisive political issue, according to Suzanna Sherry, a constitutional law professor at Vanderbilt University. And Chemerinsky says that even if the courts did decide the issue, they would want to err on the side of giving voters their choice.

“I think the court would either decide there was no standing or decide it was a political question [and decline to intervene],” Sherry says.

It would be tough for someone to prove he had the right, or standing, to sue over Cruz’s potential ineligibility in the first place. Cruz’s vice president could make the argument, claiming that he or she should be president instead, but that sounds more like an episode of the “West Wing” than an actual possibility. Or someone who objected to following a law President Cruz had signed could try to sue, arguing that Cruz had no right to enforce laws. It’s also possible, though extremely unlikely, that a state election official could refuse to put Cruz on the ballot, forcing the senator to start legal action.

In the meantime, Cruz is attempting to ignore and belittle the attacks, saying Trump is “jumping the shark.”

“My focus is on addressing the real issues facing the American people,” Cruz told reporters in Iowa.