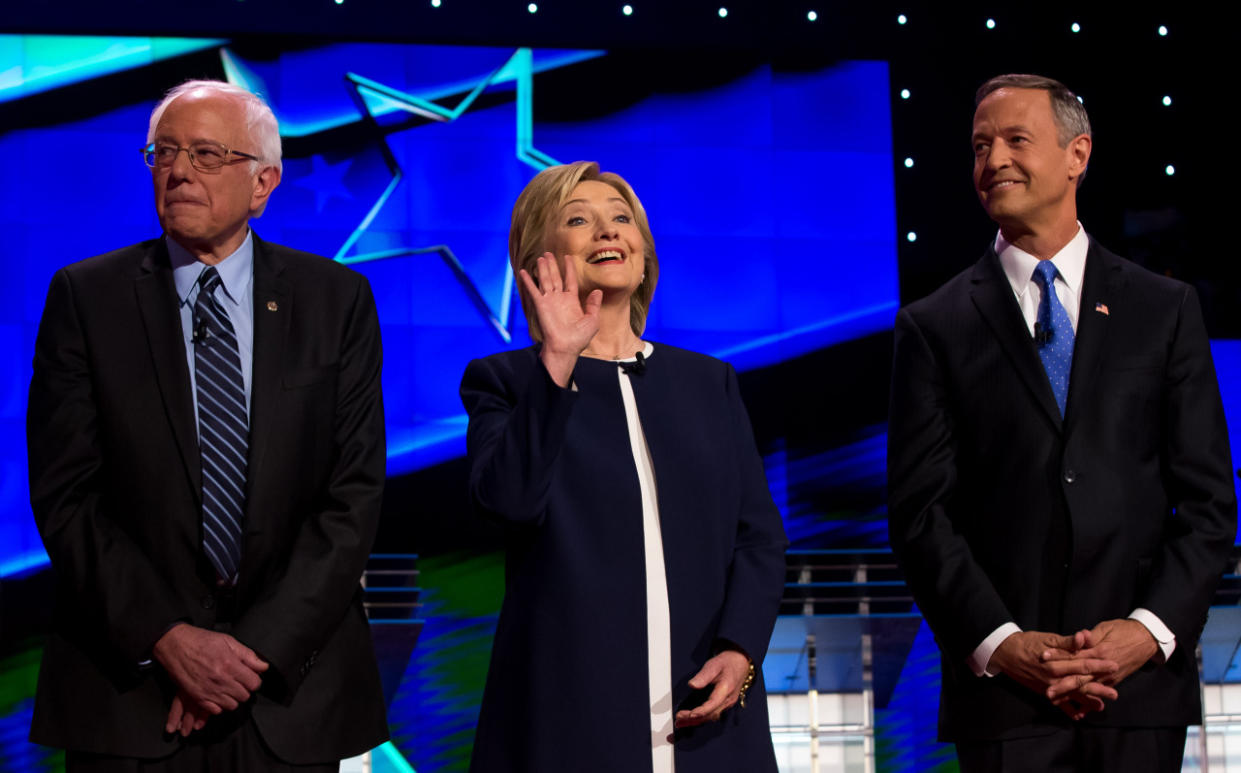

5 questions about Paris for Hillary, Bernie and O’Malley

Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton and Martin O'Malley at the 2015 CNN Democratic Presidential Debate in Las Vegas. (Photo: Erik Kabik Photography/MediaPunch)

DES MOINES, Iowa —Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders and Martin O’Malley will face off here Saturday in their second debate, their fight for the Democratic presidential nomination transformed by the devastating terrorist attacks in Paris Friday. In the wake of the deaths of 129 — and counting — the primetime showdown seems certain to focus heavily on national security, pitting the former secretary of state’s more hawkish views against the independent senator’s well-known reluctance to use force, while leaving O’Malley hunting for ways to cast himself as a plausible commander in chief.

It will also showcase the ways in which the national conversation about the so-called war on terrorism has — and has not — changed since 2004.

That year, Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry — now secretary of state — took heat from Republicans for envisioning less than total victory in the conflict President George W. Bush named “the war on terrorism.”

“We have to get back to the place we were, where terrorists are not the focus of our lives, but they’re a nuisance,” Kerry told Matt Bai in an interview published in the New York Times magazine in October 2004.

The Republican onslaught masked the fact that Bush had sketched out a similar philosophy in an interview with NBC just a few months earlier. Asked whether the United States could ever decisively win the war on terrorism, Bush replied: “I don’t think you can win it. But I think you can create conditions so that those who use terror as a tool are less acceptable in parts of the world — let’s put it that way.”

The Bush team quickly walked that comment back, insisting that the president’s strategy would yield victory. But 11 years later, it’s hard not to see that Kerry and Bush were onto something. And the national debate rages, still, over how the United States and its allies should wage what often feels like an endless war against an ever-changing enemy and cast of characters — among them al-Qaida, Boko Haram and the so-called Islamic State, which has claimed responsibility for the massacres in Paris.

Here are some questions the Democratic candidates should be prepared to answer in Des Moines:

1. How would your approach to the Islamic State differ from President Obama’s?

This is a question about policy, but it has significant political ramifications.

Hillary Clinton has already found some daylight between herself and the White House on foreign policy on Syria. She has called for no-fly zones and humanitarian corridors, options that Obama has rejected for years.

Clinton may be mindful that securing a third term for the party in the White House is historically unlikely: In recent decades, only George H. W. Bush has succeeded. Clinton has forcefully rejected the idea that she would bring about Obama’s third term — or Bill Clinton’s. But showing is more powerful than telling.

To date, her rhetoric on Obama’s domestic agenda has often sounded like “the same, but more of it.” On the bloodshed in Syria, Clinton has carefully rejected putting American ground troops in the lead of combat operations against IS (or ISIS or ISIL, as the terrorist army is also known). But she has noted that, while serving as Obama’s secretary of state, she supported arming Syrian rebels caught between IS and government forces, and he did not.

It might be tempting to say that the renewed focus on foreign policy plays to her strengths. But it’s actually extremely tricky. Sanders is sure to remind voters that Clinton voted in favor of the 2003 Iraq War while he opposed it. Without the Iraq War, there’s no Islamic State.

SLIDESHOW: Second Democratic debate >>>

The self-described democratic socialist from Vermont used that line of attack in the first debate. “I will do everything that I can to make sure that the United States does not get involved in another quagmire like we did in Iraq, the worst foreign policy blunder in the history of this country,” he said.

Sanders has supported the use of force before — the war in Afghanistan, Bill Clinton’s air war against the Serbs — and backs airstrikes against the Islamic State. In the first debate, O’Malley also supported Obama’s approach while criticizing Hillary. The former governor’s official website features a speech on national security in which he called some Americans’ wish to disengage from the world “understandable, but not responsible.”

But Obama has reshaped the terrain with his decision to base up to 50 elite U.S. troops inside Syria. Will Clinton, Sanders and O’Malley support that decision? Promise to roll it back? Or offer up a politically expedient variation on “I am keeping my options open”?

Obama acknowledged these tensions in October. “There’s a difference between running for president and being president,” he said, emphasizing that the decisions made in the White House Situation Room “require, I think, a different kind of judgment.”

2. Will you promise to be more like President George W. Bush?

Just six days after the 9/11 attacks, Bush visited the Islamic Center in Washington, D.C., and declared “ Islam is peace.” He’ll always be remembered more for ordering the invasion of Iraq than for spending an enormous amount of time and energy pleading with Americans to embrace their Muslim fellow citizens, and to not judge all of Islam by the actions of its fanatics. (I took a searching look at his rhetoric of the war on terrorism here.)

It’s not a message Obama delivers quite as often, though his outreach has included dramatic steps like his 2009 speech in Cairo and smaller gestures like inviting the so-called “clock boy” to the White House.

What about his Democratic would-be successors? Given that some conservatives have used the attacks to argue against more permissive immigration policy, how will Democrats react?

3. What specific steps would you take right now to help France?

Martin O’Malley should pray that he gets this question, and he should prepare for it.

Why? Because voters still processing the horrifying images from Paris are going to be asking themselves: “Can you imagine this person as president, leading the nation in wartime?”

Frontrunning Hillary speaks the language of foreign policy fluently and has been involved in a wide array of major national security decisions, from the raid on Osama bin Laden’s lair in Pakistan to the deposing of Moammar Gadhafi in Libya. But Bernie’s reluctance to use force closely matches the mood of the Democratic Party’s base, which also backed Obama over Clinton in 2008 because of his promise to withdraw troops from Iraq and follow a less-interventionist foreign policy than Bush.

O’Malley, a former governor of Maryland, didn’t have a memorable foreign policy moment in the first debate (unless you winced when he misspoke and said Bashar Assad, Syria’s dictator, had invaded his own country). He trails far behind both of his rivals in national polls, and this debate may be his last chance to change the dynamic of the race. Even a strong, detailed, knowledgeable answer may not be enough to save his campaign, but failing to have one might end it.

4. Does Congress need to authorize the war on the Islamic State?

That’s right: I called it a war. It’s undeclared, like so many of the United States’ military campaigns in the last 70 years. But it’s unmistakably a war. You could even argue that Obama invaded Syria — placing elite troops there against the government’s will. American legislators last formally declared war in World War II, but at least they formally authorized the war in Afghanistan and the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Congress has grilled senior officials about the president’s IS strategy, and Congress pays the bills for it, but Congress has yet to take up its basic Constitutional duty to vote on authorizing the use of military force.

The reasons are complex but boil down to this: Democrats want more restrictions on the president’s war-making powers, Republicans want fewer. The White House’s grudgingly submitted authorizing legislation stalled the moment it arrived on Capitol Hill, and Obama does not seem inclined to press the issue.

The White House says it has the legal authority it needs in the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) in Afghanistan and sometimes cites the 2002 AUMF for Iraq, or the president’s constitutional powers as commander in chief.

But not all congressional Democrats buy that. What do the party’s presidential contenders think?

5. Do we need a top-to-bottom overhaul of the war on terrorism? Can we win it?

George W. Bush declared a war on terrorism not quite 12 hours after al-Qaida used hijacked airplanes as guided missiles and completely transformed the world. It’s been 14 years. The United States has tried all kinds of strategies, see-sawing between Bush’s invasion and occupation of Iraq and Obama’s withdrawal and more hands-off approach. America has outraged the world with unprecedented spying, with torture, with assassination, with the indefinite detention without trial of suspected terrorists at Guantanamo Bay.

In November 2012, Jeh Johnson — then general counsel at the Pentagon, now the secretary of Homeland Security — predicted in a speech that there would come a “tipping point” against al-Qaida, at which point the group will have been “effectively destroyed.”

Obama has vowed to “degrade and destroy” the Islamic State, while acknowledging that he will bequeath the military campaign to his successor.

In September 2014, I asked White House press secretary Josh Earnest to define “victory” over the Islamic State. “I didn’t bring my Webster’s Dictionary with me up here,” he quipped, making light of the difficulty of explaining Obama’s ultimate goal. His extended answer boiled down to keeping the pressure on the Islamic State so that it cannot launch attacks on American targets. The Paris attacks call that approach into question.

Political campaigns tend to favor chest-thumping predictions of total victory. Both Kerry and Bush were punished for injecting nuance into the discussion. But if the short-term question is about helping France and punishing the authors of the attacks, the longer-term puzzle of defining America’s national interests and deciding the best means to advance them belongs on the president’s desk.