Feds offer little guidance to Islamic State recruits too young to prosecute

(Photo illustration: RJ Sangosti/The Denver Post via Getty Images; AP; AP)

Aasha, 17, looked up from her hands and saw the faces of six of her closest friends staring back at her. They awkwardly sat in a circle in a small counselor’s office in their high school.

“Why would you do something so stupid?” one of Aasha’s friends, Badra, finally asked.

“We just wanted to go over there to study,” Aasha replied.

“There’s a library right here,” Badra said. “You can study all you want.”

The girls grew up together in a dusty suburb of Denver called Aurora, attending the same mosque with their families on Parker Road. They were like sisters, sharing secrets, complaining about their strict immigrant parents and talking about boys since they were in elementary school.

Intense high school friendships end for all kinds of reasons — boys, social ambition, different schedules. But what this circle faced was far more dramatic — and more hurtful. They were torn apart by the Islamic State, whose recruiters quietly seduced three girls in their group online without any of the others even noticing. Now, the six girls faced down their former friend and weren’t sure they had ever really known her.

Just a week before this conclave at the counselor’s office, Aasha, her 15-year-old sister, Mariam, and her 16-year-old friend Leyla vanished without so much as a goodbye to their family or friends. (Yahoo News has changed the girls’ names to protect their identities because they were minors when they attempted to travel to Syria. Badra’s name has also been changed to protect her identity.) They skipped school one Friday, took a cab to the airport and boarded the first flight on their lengthy itinerary to the Middle East.

The girls were on their way to Syria to join the most feared terrorist organization in the world. They had been communicating with IS recruiters and sympathizers for months using secret online identities, and their views became more radical by the day. The girls were taken in by their new vague ideology. They believed Syria would be a utopian place of freedom and safety for them and their religion, instead of a brutal caliphate known for forcing women and girls into sexual slavery and beheading or burning alive its ideological opponents.

Now they were in the counselor’s office instead of the caliphate, facing a set of very teenage problems that they had hoped to escape by joining an adult group of foreign fighters. Their friends were angry that they had ditched them and had kept them in the dark about their plans. When the girls first were reported missing, their friends assumed they had been kidnapped — IS never even crossed their minds. It wasn’t until one of them noticed that Mariam had sent a Snapchat that looked like it was taken at the Denver airport’s Baskin-Robbins that they began to piece it together.

The girls were caught in Frankfurt, Germany, a day later, as they were changing planes to go to Turkey. Because they were all under 18, they were returned to their parents and not charged with any crime, according to two former FBI agents in Colorado who are familiar with the investigation. Their parents were given stern warnings to monitor and limit the girls’ Internet use.

A passenger walks through a terminal at Frankfurt airport. (Photo: Ralph Orlowski/Reuters)

Just a couple of months in age made the difference between treating these teens as hardened terrorists facing serious prison time and wayward girls in need of more guidance from their parents. Only one town over, in Arvada, 19-year-old Shannon Conley was given a four-year federal prison sentence for attempting to travel to Syria to marry a fighter she met online. Their cases are not identical: Conley had expressed a desire to actually fight with IS, while the three girls appeared to have a more nebulous plan to provide support to the group. But there’s little doubt that the teens would have faced charges for their actions had they been of age.

The legal threshold for prosecuting juveniles in federal court is high, and it is discouraged by the Justice Department leadership. That presents prosecutors with a conundrum, given IS’s cunning ability to recruit teens. At least two minors have been charged federally with attempting to aid the group, but these cases are the exception. Some juveniles who have taken steps to join up have been sent back to their communities with a tough lecture — but little guidance — from federal law enforcement.

This feature of the federal system presents an enormous challenge — rehabilitating aspiring fighters and reintegrating them into the community — to families, schools and religious leaders who are wholly unprepared for the task. The United Kingdom, Pakistan and other countries provide government-funded “de-radicalization” programs, but nothing of the sort exists in the U.S. Instead, the problem is effectively dumped in the laps of parents, teachers, clerics and friends.

How Aurora and other communities around the country reintegrate children who have been lured by IS is a question with critical national security implications. The stakes are high. If these kids do not find a new path, they could try to travel to Syria again, or, worse, attempt attacks on U.S. soil.

“If you’re not going to incarcerate them, then you have to provide that off ramp to them to get them de-radicalized,” said Rep. Michael McCaul, R-Texas, chairman of the House Committee on Homeland Security, which released a report last month chastising the federal government for failing to develop adequate alternatives to prosecution in these cases.

Shannon Conley’s yearbook photo, left; Conley during U.S. Army Explorer training, right. (Photos: handout; Facebook)

***

The case of Aasha, her sister Mariam and her friend Leyla illuminates how skillfully IS preys on the young, targeting the vulnerabilities of high school kids who struggle with self-esteem, fitting in with their peers, the tribulations of adolescent dating and other social anxieties. The children of immigrants, often caught between dueling cultures, can be especially susceptible to charismatic recruiters as they search for firm identities.

All three girls were trying on new personalities on myriad social media sites, and looking for affirmation from older, seemingly glamorous people who were already in Syria. None of the girls have spoken publicly since the incident, and they and their parents did not respond to requests for interviews. But the girls’ now-deleted social media profiles and the observations of their friends provide a window into their transformation from regular teens to aspiring jihadis.

Aasha’s friends describe her as one of the boldest girls they knew, always up for a dare and trying to make the other girls laugh. “[Aasha] was crazy,” Badra says.

As a young teen, Aasha raved about her friends and family on the social media site Ask.fm. “I can’t live without my family and friends,” she said in answer to a question. “I love them all they are amazing,” she said of her friends in another post. Her hobbies were “playing tennis, swimming and being with my family and friends.”

Like many teens, she went through big changes in high school. Her search for identity led her to an even more orthodox embrace of her religious roots. In her sophomore year, Aasha began dressing far more conservatively, trading out her jeans and T-shirts for a full abaya that covered everything but her head, feet and hands. She appeared to lose some of her old sense of fun, her friends said. On her Ask.fm account, she wrote that she wouldn’t go to prom because she believed it was “haram” — forbidden by Islam. She said her biggest fear in life was “displeasing my creator” and showed a fascination with an afterlife in paradise, called Jannah. “It makes my day,” she wrote of Jannah.

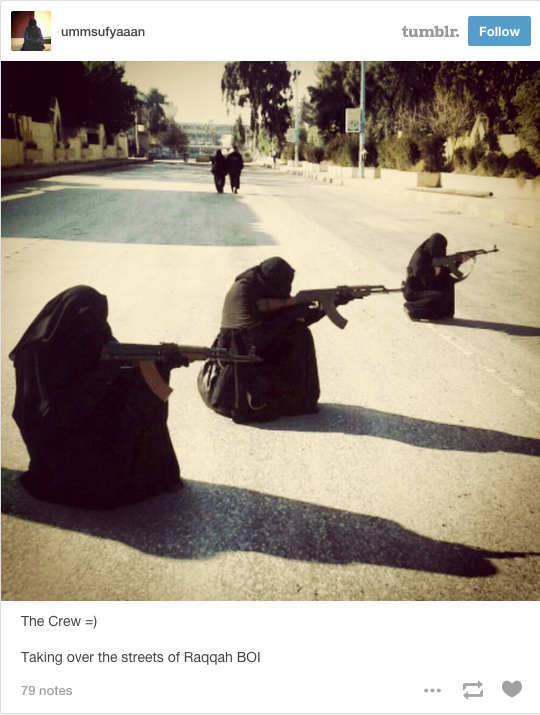

Screengrab of a Tumblr post of Umm Sufyaan, a woman who claims to belong to the Islamic State and was in contact with at least one of the Denver girls. (Photo: Umm Sufyaan via Tumblr)

Aasha also began spending more time with her friend Leyla. Leyla had always been more serious and more devout than the rest of the group, though she, too, had grown more fervid in her beliefs sophomore year. Leyla, whose family is Sudanese, showed up in Denver from Nebraska in eighth grade. “She used to be a regular teenager; she used to wear jeans,” Badra said. “She was just regular, like one of us.”

But then she began to close off and reject her former friends. Leyla told Badra she couldn’t hang out with her anymore because she plucked her eyebrows. She abruptly dropped another friend because she was Christian. In the middle of English class during her sophomore year, she told her teacher he was a “kafir” — an infidel. He just laughed it off.

Leyla’s parents desperately tried to get her to lighten up — to wear nail polish for a family wedding, to go out more and be with her friends, to dress less religiously. But she refused, complaining about them on her secret Twitter account, where she was able to experiment with her new, more radical identity. (“Unsupportive parents are such a roadblock,” she tweeted the July before she left, adding that they wouldn’t let her be as devout as she wanted to be.)

Mariam, Aasha’s little sister, seemed more interested in romance than the finer points of religious doctrine. On her Facebook account, she shared photos, dreaming of a Muslim husband who would help her reach paradise when she was just in eighth grade — a version of the knight in shining armor fantasy many girls share. But closer to their attempted journey, Mariam wrote that she had realized her old friends were no longer her “true friends” because they did not support her religious pursuits.

Female IS recruiters often paint a rosy picture of marriage in the caliphate as a tactic to lure young girls to Syria. It’s a strategy that would have hit home for these three girls, according to their friends.

“They’re all very obsessed with the reality of marriage,” Badra said. “They’re really in love with that. I guess they just grew up with the mentality that you can’t really leave your parents and have fun until you get a husband.”

Whatever tipped them over the edge, the girls appeared to have made the decision by last summer. The two older girls began working at Walmart to save up extra money, and Aasha asked several friends if anyone could give her a ride to a pawnshop to help her hock jewelry. One September day in the library, Aasha approached her friends and told them how much they meant to her. “I love you,” she said. “You guys know you are my closest friends ever since we were little.” Her friends looked up at her, confused, and told her they loved her too.

In just a couple of weeks, she would be gone.

***

Though Aasha, Leyla and Mariam will not be prosecuted for trying to join IS because they are minors, the FBI officially classifies their case as still open, and the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Colorado will not comment on them.

The FBI impressed upon the girls’ parents that they were lucky their kids were not either dead in Syria or facing serious prison time. “They were very supportive, and very willing and eager to set some restrictions on these young ladies and act as parents,” said a former FBI agent involved in the case.

The reality is the authorities treat these kids as garden-variety juvenile delinquents: Send them home and let Mom and Dad guide them back to idyllic American lives.

But the process of reintegrating children who want to join a foreign fighter group is complex and varies by case. “It’s unrealistic to expect the same parents who weren’t able to stop or prevent initial radicalization to somehow now be able to police their daughters’ behavior of going down the same pathway,” said John Horgan, an expert on terrorism and political violence at Georgia State University.

Other countries recognize this. Yousef Bartho Assidiq, who runs an organization called JustUnity that attempts to dissuade Norwegian youths from joining IS, says his first task is to find out why the young person was interested in joining the group in the first place. This can vary from finding love, to a desperate need to belong, to wanting an escape life’s problems. He then works with the teen to craft an alternative vision for their life, addressing their problems one by one. This can take months.

Screengrab of a still of Mohammed Hamzah Khan, a 19-year-old Bolingbrook, Chicago, man accused of trying to head overseas to fight for the Islamic State. His two siblings, both minors, were not charged. (Photo: ABC 7 Chicago)

“They need someone to work with them,” Assidiq said. “Parents at this time also need guidance and counseling.”

But this kind of support isn’t being offered to teens here, despite IS’s increasing allure and the complicated nature of rehabilitating teens who are swayed by the group. IS-related prosecutions ramped up in the U.S. from one case per month in 2014 to seven per month in the first half of 2015 . But there are young people who are never prosecuted, such as the 16-year-old brother and 17-year-old sister of Mohammed Hamza Khan, 19, who were caught at the airport on their way to Syria. The Justice Department doesn’t say how many times it has exercised prosecutorial discretion in this way. “I think people would be surprised at how often this is happening,” the FBI agent said.

Part of this hands-off approach is a result of how hard it is to try minors in federal court. Tim Heaphy, a former U.S. attorney in Virginia, only tried one juvenile during his five-year tenure — a 15-year-old who set fire to a black church. “Trying juveniles in court is very hard to do,” Heaphy said. Attorneys must prove to the judge that there’s no lower court the defendant can be tried in and that the seriousness of the crime merits the strong hand of the federal system. Even if the judge agrees, a prosecutor would then face a potentially skeptical jury uninterested in locking up a teenager who was convinced by online recruiters to join IS.

“There’s a sense that we just can’t go around locking up a whole bunch of teenagers that are not of age,” said Karen Greenberg, the director of Fordham’s Center on National Security. “There are a lot of kids they are choosing not to prosecute.” Greenberg believes giving these kids — most of whom have no prior records — a second chance is a good thing.

In Denver, law enforcement’s more hands-off approach earned the FBI and Justice Department goodwill and trust from the Muslim community, a fortunate consequence of the difficulty of prosecuting minors.

“The community did appreciate the effort of [the authorities] to bring them back safe and not charge them,” said Hafedh Ferjani, president of the Denver Islamic Society.

The Justice Department understands that the parents of kids who are vulnerable to falling under the sway of extremists need support. Since the girls tried to leave last year, the local U.S. Attorney’s Office and the FBI have given presentations to parents and kids about how to avoid being targeted online by IS supporters. Marc Raimondi, spokesman for the National Security Division of the Justice Department, said “prevention and deterrence” of violent extremism is a top priority for the department. Last year, the Obama administration tapped several districts to experiment with programs that deter at-risk youth from wanting to join extremist groups. None of the programs, however, are designed to handle kids who already attempted to join IS.

A Homeland Security Committee report released last month on combating foreign fighter travel chided the Obama administration for failing to develop cohesive alternatives to prosecution — called “off ramps” — for aspiring foreign fighters. Law enforcement can either lock someone up or let them go — a binary choice that doesn’t address the root cause of why someone wanted to join IS in the first place.

Only one de-radicalization experiment has ever been tried in the U.S., on an 18-year-old in Minnesota. He was allowed to live in a halfway house and given civics and religion lessons while awaiting prosecution, but was sent back to prison after a knife was found in his room. “Authorities have made some attempts to pursue alternatives to prosecution, but they do not appear to be based on any overarching guidance or best-practices,” the lawmakers said in their report. “So far, these efforts to pursue ‘off-ramps’ have been ad hoc and lack a systematic framework.” Rep. McCaul, who chairs the committee, pointed to the example of drug courts, which allow judges to sentence drug offenders to treatment instead of jail. “There’s nothing like that with radicalization,” McCaul said.

Some cities are beginning to look at developing off ramps to prosecution for these cases, according to George Selim, director of the Office for Community Partnerships at the Department of Homeland Security. (The newly created office’s mission is to counter violent extremism.) But those initiatives will be designed and run by local FBI and Justice Department offices. “It can’t be a Washington-focused top-down program,” he said.

The FBI agent who worked on the three girls’ cases worries that returning them to the same environment that radicalized them without any further guidance is irresponsible.

“Simply the fact that we returned these three girls to Colorado doesn’t change what motivated them to leave in the first place,” he said.

****

A woman walks through a playground at the apartment complex where one of the three teen girls who attempted to travel to Syria lives. (Photo: RJ Sangosti/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

Almost a year has passed since the three Denver girls set off on their ill-fated trip to Syria. Some aspects of their lives have changed dramatically — they no longer are close with their former group of friends, or with each other. Aasha and Leyla, once inseparable best friends, no longer speak to each other. But much has stayed the same: They still spend time with their families in Aurora and attend Overland High School.

The authorities left it up to the girls’ parents to mete out punishment, which has been applied unequally by the two families.

Ironically, Aasha and Mariam’s parents seem to give the sisters more leeway now than they did before they attempted to join IS. They were so grateful to have their daughters back that they bought them new clothes and phones, and are less strict than they were before, according to Badra.

Mariam is on Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram again, though Twitter — where she and her sister followed IS members and supporters — is still forbidden.

For 17-year-old Leyla, it’s been a different story. She did not return to Overland last year, and instead took courses from home. She’s not on any social media networks.

The one time her former friends saw her in the hallway at Overland last year, picking up some course materials, they waved. Leyla stared at them and then looked at the ground.

At the end of August, Leyla returned to school for the first time since her plan to join IS upended friendships and families. Badra believes Leyla and Aasha’s families have forbidden the girls to be friends, given the trouble they got into together.

“Things will never be back to normal,” their former friend said. “They changed everyone’s lives.”