Don’t erase Woodrow Wilson. Expose him.

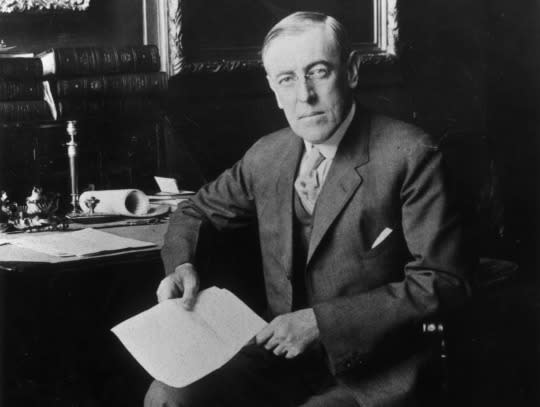

Woodrow Wilson was a visionary statesman and, at the same time, a racist with repugnant ideas. (Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Several years ago now, a book editor suggested I write a biography of Woodrow Wilson. I declined, because, for one thing, I’m not really a historian, unless you go by the Twitter standard, in which anything that happened during the last presidency is considered obscure. And after watching “Cast Away” 100 times, I knew I could never take on a Wilson project without drawing a face on a volleyball and propping it up on my desk, and from there it would be a short leap to madness.

What I did not think at the time was that Wilson, having been a racist, a bad husband and a demonstrably unpleasant guy in general, did not deserve to have his legacy as a statesman remembered or celebrated. Which is pretty much the case that’s now gaining ground at Princeton, where students are agitating to have Wilson’s name and image expunged from campus.

This, amid a rash of similar protests around the country, is what university educators everywhere might call a “teachable moment” — if only they can summon the courage to actually teach.

Wilson, as you may know from your history classes (or from one of the exhaustive biographies that actual historians have written), was both a Princeton alum and the university’s president before he went on to become the governor of New Jersey and, in 1912, only the second Democrat since Reconstruction to win the White House. He led the country through the First World War, founded the League of Nations and established the Federal Reserve system as we know it, among other things.

Wilson can fairly be credited, along with Theodore Roosevelt, with having pioneered the modern concepts of American internationalism and progressive government. For this, in 1948, Princeton named its renowned school of public policy and international affairs in his honor.

(Also, the state of New Jersey awarded Wilson its equivalent of British knighthood, putting his name on a drab rest stop along the turnpike. Dare to dream, Chris Christie, dare to dream.)

What you might not have known about Wilson — and I admit, this was hazy in my memory as well — is just how execrable a human being he seems to have been. Wilson was a fervent segregationist who apparently went to some effort to separate the races in federal buildings. As president, he screened “Birth of a Nation,” the infamous film glorifying the Ku Klux Klan and its philosophy, at the White House.

As the New York Times’ Andy Newman noted in a very good overview this week, Princeton did not admit a single black student during Wilson’s tenure, setting it decades behind other Ivy League schools that took a more enlightened approach. This was not a coincidence.

Thus the reason that a group of students calling themselves the “Black Justice League” has recently demanded that Princeton remove Wilson’s name from both the public policy school and a residential college that features a large mural of the man in its dining room. The students, about 15 of whom occupied the current president’s office in protest, are also insisting that the university impose a course on “the history of marginalized peoples,” which, if you haven’t spent much time on an elite campus lately, is also known as the entire humanities curriculum.

Truth be told, I probably would have gotten behind this kind of protest when I was running my college paper. Every generation of students struggles anew with the ideals of social justice and identity; in my day, it was breaking the back of apartheid in South Africa. Holding the collegiate institution accountable for its past is a way of serving notice on all the larger institutions in the society.

And those of us who are white can only imagine what it’s like to be the African-American student who has to walk through the doors of the Wilson school every day, or eat dinner beneath his mural every night and stare into the exalted image of a man who didn’t believe you should be treated as an American, or even as a person.

But there’s a bigger picture here, and at least a couple of reasons to defend Wilson’s place on campus.

First and most obviously, you’re going down a perilous road when you start judging historical figures by modern standards, separating morality from its context. Wilson, a Virginian, was born into the heart of the Confederacy five years before it seceded and a full century before the civil rights movement gained momentum. As a segregationist, he may not have been typical of his Ivy League peers, but he was hardly an outlier among white Southerners.

If you’re going to indict Wilson for the crimes of another century, then where do you stop? How about Amerigo Vespucci, who loaded his ship with “savages” to be sold at market? Or the slave-owning George Washington? How many names and monuments are we supposed to erase from the record?

More to the point, though, is that today’s students have grown up in a society that increasingly eschews moral complexity. They’ve never known a time when you can’t choose your own media, your own history, your own truth. Theirs is a binary world where everyone is either all good or all bad, where the only reality worth hearing online or on cable TV is the one that reaffirms your preconceptions.

But history is complicated, and so are the people who make it. The messy reality is that great people sometimes do terrible things, and terrible people sometimes do great things. To discard all the actors we find abhorrent, along with all the things they might have accomplished, is to deny the vexing contradictions of humanity — which is exactly what real knowledge is about.

And this is where a lot of these university administrators are failing their students spectacularly right now. Their job isn’t to root out “microaggressions” or “trigger words,” to sterilize campus life in an effort to stave off discomfort.

Their job is to make students understand that truth is often confounding and uncomfortable — that, as F. Scott Fitzgerald put it, “the test of a first rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” (I’ve quoted this before, but in the current climate, it bears repeating.)

Here’s a solution to the Wilson conundrum. If I were the president of Princeton, instead of cowering before protesters and empowering some commission to decide Wilson’s fate, I’d leave his name right where it is.

But I’d put a plaque in the lobby of the public policy school explaining that Wilson was a visionary statesman and, at the same time, an avowed racist with repugnant ideas. I’d add the same context, incidentally, to the video tribute at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, where I’ve been a resident scholar.

Exposing Wilson publicly would send the right message to this and future generations, which is that times change, legacies are complicated and leaders are flawed.

I’d let the rest stop speak for itself.