A woman enslaved by a major Harvard donor fought for reparations and won. Why her story still matters.

Near the close of the American Revolution, Belinda Sutton told of how enslavers snatched her from her parents at around 12 in an African hallowed grove, transported her across the Atlantic Ocean, and bound her to Harvard benefactor Isaac Royall, Jr.

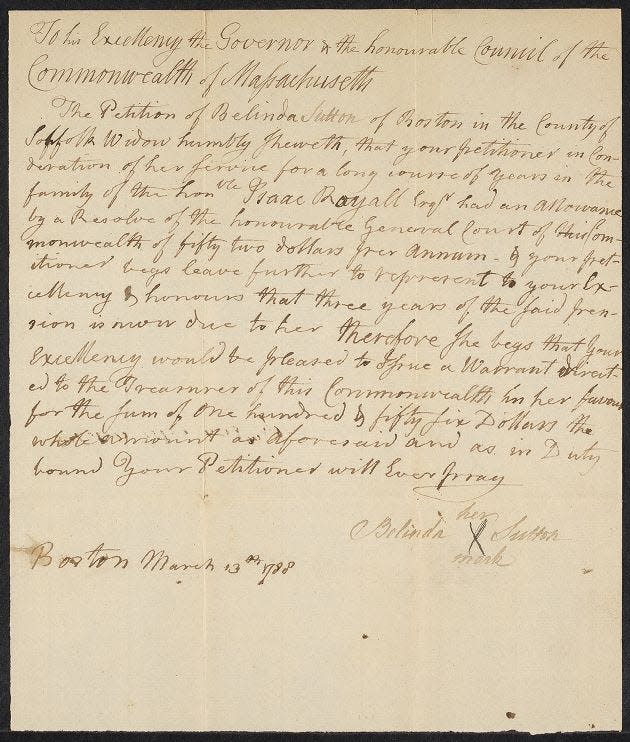

Sutton, by then a free woman, shared her story as part of a 1783 reparations petition to the Massachusetts General Court after decades of "ignoble servitude."

Sutton's face, the petition read, is "now marked with the furrows of time," and her frame feebly bends under years of oppression after being denied "enjoyment of one morsel" of Royall's immense wealth from decades of work.

RELATED: Harvard announces $100M to fund efforts to redress its ties to slavery

RELATED: California reparations task force set to vote on compensation for Black citizens

Lawmakers awarded Sutton and her daughter, Prine, a yearly payment of 15 pounds and 12 shillings, marking one of the first known reparations cases in the nation's history. Sutton was only given a few payments after getting her freedom after Royall, a loyalist to the crown, fled the colonies.

Now, around 240 years later, Sutton's reparations case and life illuminate a longstanding call for redress for the millions of people enslaved in the Americas, historians said. At the same time, the movement for reparations has grown, moving from Sutton's case against her enslaver to calls for redress from academic institutions and others across society.

"We find as we talk about Belinda and others, white and Black, is that people were thinking about the justice, the morality and the economic value of reparations in whatever form early on," said Roy Finkenbine, a University of Detroit Mercy professor and director of the school’s Black Abolitionist Archives.

Harvard outlines connections to slavery

With a $100 million commitment, Harvard University last month joined a movement of schools such as Brown and Georgetown universities that have become more explicit about their ties to slavery and the work needed to identify and address the harm of bondage. In 2006, Brown University issued a watershed report about its founders’ ties to enslavement. The school also created a center to research slavery and injustice.

In 2020, California set up a task force to compensate for the enslavement of Black Americans. Federally, reparations advocates have asked the Biden administration to sign an executive order to study reparations after a long pushed Congress to pass H.R. 40, a bill that creates a commission for the study of reparations.

The issue remains somewhat contentious as both Democrats and Republicans have not supported paying out reparations. Some, such as members of the California reparations task force, say only those who had been enslaved should get reparations. Others have commented that it would be difficult to decide who should get the assistance hundreds of years later.

Text with the USA TODAY newsroom about the day’s biggest stories. Sign up for our subscriber-only texting experience.

Nkechi Taifa, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Reparation Education Project, said Sutton's story is part of a long line of reparatory injustice, ranging from the Middle Passage, short-lived calls of 40 acres and a mule for formerly enslaved people more than 150 years ago to unheeded demands for racial justice today.

"There's a direct line between the enslavement era and what is happening today," she said. "So, it's a good thing that entities are looking at these connections, are doing the studies, and are engaging with communities to see just how we can confront some of these unresolved issues."

Harvard's report pointed out the university played a role in subjugating non-white people by holding enslaved people on their campuses, propagating scientific racism that endures today. Other research has pointed out that Havard heavily recruited the progeny of slaveholders in the West Indies, the American South and elsewhere.

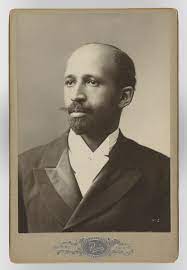

Harvard's report also highlights its Black graduates who later challenged those systems. It specifically names sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois and Charles Hamilton Houston, a dean of Howard University Law School who earned the moniker "The Man Who Killed Jim Crow."

Between the university's founding in 1636 and the end of slavery in the commonwealth in 1783, Harvard faculty, staff, and leaders enslaved more than 70 people, the school said in its report. It noted the number is "almost certainly an undercount."

A number of the 70-plus individuals were only listed by their first names such as Scipio, Zillah and Flora, and others only identified as "The Moor" or "The Spaniard."

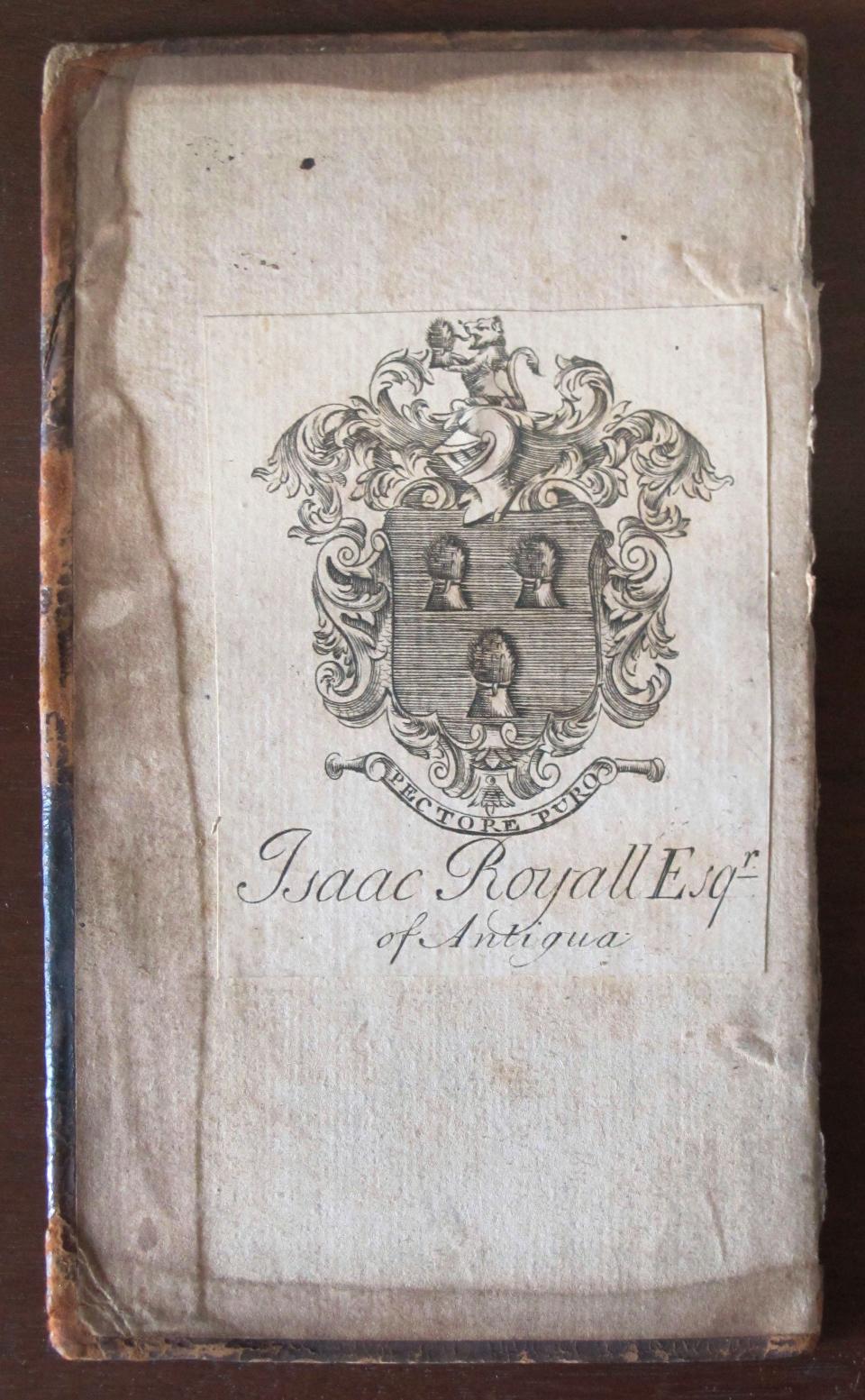

Also named in the report is Royall, one of the wealthiest enslavers in Massachusetts at the time, who held Sutton and at least 59 others in bondage on his plantation in Medford. Most other enslavers in colonial Massachusetts held a handful of people in bondage.

The law school's shield featured the Royall family's crest, withdrawn in 2016 after student protests. Others disapproved of the removal, calling instead for a historically sound interpretive narrative.

Royall family grew richer from slavery

The Royall family generated a sizable portion of their wealth from a plantation on the Caribbean island of Antigua.

After Royall died in 1781, his estate gave Harvard perhaps the most well-known gift: land the university sold, the school said. Harvard later created the Royall Professorship of Law, Harvard's first chair in law and one of the most regarded positions in American legal education.

The chair was at the root of the decision to have a law school at Harvard, said Royall professor of law Janet Halley in earlier remarks. The first holder of the chair, Isaac Parker, proposed the start of the law school.

Royall's sister, Penelope Royall Vassall, also owned a person named Cuba Vassell, who lived on Harvard's campus.

"There's nothing that this family had that wasn't based on slavery," said Kyera Singleton, executive director of the Royall House and Slave Quarters museum.

Singleton said it is impossible to acknowledge the beauty of the plantation without talking about the people like Sutton, who were forced to live there and maintain the vast estate.

"And so there's no way you can just look at the property, look at the house, think about all of the wealth that this family had, all of the beautiful furniture they had, and not think about the violence and violation of slavery," she said.

Although she is not listed among those mentioned in the Harvard report, Sutton's life is intertwined with the growth of slavery in the colonies and the ongoing push to redress the nation's dark history.

Mary Elliott, curator at the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture, said Sutton knew her worth.

“She talks about all that she lost,” Elliott said. "Not just when I got here, this is what happened to me, but what was taken from me.”

Sutton recounts horrors in reparations case

Born near the banks of the Volta River in what is now considered Ghana, Sutton described an ideal childhood — a place where the valleys were "loaded with the richest fruits" and mountains were "covered with spicy forests."

She recalled praying to the goddess Orisa in the sacred groves with each hand in that of a "tender" parent.

Those bucolic scenes would be suspended when she got an impression of the “cruelty of men.” Sutton said men with faces like the moon stormed her village with "bows and arrows" that were like the “thunder and the lightning of the” clouds.

She said the men rushed into the sacred grove, ripping her away from her parents who were deemed too old for the journey to the Americas.

"She was ravished from the bosom of her Country, from the arms of her friends – while the advanced age of her Parents, rendering them unfit for servitude, cruelly separated her from them forever!" the petition read.

Sutton described the horrors of the Middle Passage, or what she calls the "floating world."

She witnessed new sights such as the Atlantic Ocean and ships but it did not distract her from the 300 Africans in chains. The petition notes that the "excruciating torments" of the Middle Passage led some to cheer at death.

Once in the Americas, Sutton soon realized that her "doom was slavery," a fate she feared only "death alone was to emancipate her."

Sutton found little enjoyment in being enslaved to the Royalls, in which she looked at the splendor of their Medford, Massachusetts, plantation, but received no compensation.

She had two children. Historians have said that Joseph, her son, would've likely been sold into slavery. Prine, her daughter, who had a disability, lived with her after moving to Boston when the Legislature freed them.

In Boston, she found a thriving free community, historians said. She met lawyers and the likes of Prince Hall, an abolitionist leader who worked successfully to file freedom petitions for himself and others.

Since Sutton was likely illiterate, some historians presume that Hall wrote the petition. If he is the writer behind the petition, he co-opts the language of the revolution and enlightenment period to make arguments in favor of a pension for Sutton.

"Fifty years her faithful hands have been compelled to ignoble servitude for the benefit of an Isaac Royall," the petition read. Until, as if the nations "must be agitated, and the world convulsed for the preservation of that freedom which the Almighty Father intended for all the human Race, the present war was Commenced."

Historians and curators have noted various reasons the Massachusetts General Court awarded her petition. Some have said since the commonwealth was not as dependent on the institution of slavery as other colonies, the board would have fewer reasons not to award Sutton the funds. Other say awarding the reparations were more about the punishment of Royall, who had aligned himself with their oppressor, Great Britain.

"They didn't award her the funds because they cared about her and her well-being. I think it was more to punish Isaac Royall, Jr., for being a loyalist, and I think that's part of the reason she never actually received more than (a few) payments," said Singleton of the Royall House and Slave Quarters.

Regardless of the motives for not paying her, the money would have meant a lot for Sutton and Prine, and their survival.

The petition offers insight into what the payments would have meant to Sutton’s family. It says, in part, that having her own money would be her way out of the estate of Royall and prevent her and her daughter "from the misery in the greatest extreme, and scatter comfort over the short and downward path of their lives."

Long after she received the two payments, Sutton continued to file claims for reparations until, the 1790s, when she likely died or moved, historians have said.

Raymond Winbush, a professor at Morgan State University in Maryland and director of the Institute for Urban Research, said Sutton's story serves as a bridge from the freedom petition of Elizabeth "Mum Bett" Freeman to later pushes for reparations by Callie House, Queen Mother Audley Moore and beyond.

“The women really carried the water historically for the reparations struggle,” he said. “There's no doubt about that."

And by leaving her story behind and fighting for reparation, Sutton's case shows Black women have always been their own political agents, said Singleton.

"They've always been advocating on behalf of themselves and others," she said. "They've always been defining freedom on their own terms. And they've also always been asking to be fairly compensated and to receive justice when they have endured."

Tiffany Cusaac-Smith covers race and history for USA TODAY. Click here for her latest stories. Follow her on Twitter @T_Cusaac.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Reparations for Black Americans? Harvard case shows history's horror