Re-telling black history: 3 women on navigating personal encounters with racism

Talking about racism is important precisely because doing so makes us uncomfortable. When people share their experience with racism and hate, it helps us understand each other better and brings us closer to conceptualizing a more accurate version of our country’s history.

As part of USA TODAY’s 1619 Project, we collected personal stories from readers.

The final installment of USA TODAY’s 1619 Voices Project features three women who told us about their encounters with racism, and how they confronted and overcame it. In one instance, a reader told us how she learned about hateful crimes committed by her white ancestors.

“We’re telling their stories because we want to create a dialogue, helping people understand why we avoid talking about race,” said USA TODAY Washington correspondent Deborah Barfield Berry.

“We also want to show how confronting our discomfort can educate others and sometimes lead to healing,” Berry said.

More: Black History Month essay: I searched a continent a world away, hoping to find 'home'

More: #SiliconValleySoWhite: Black Facebook and Google employees speak out on big tech racism

More: Don't forget Justice Clarence Thomas in Black History Month celebrations

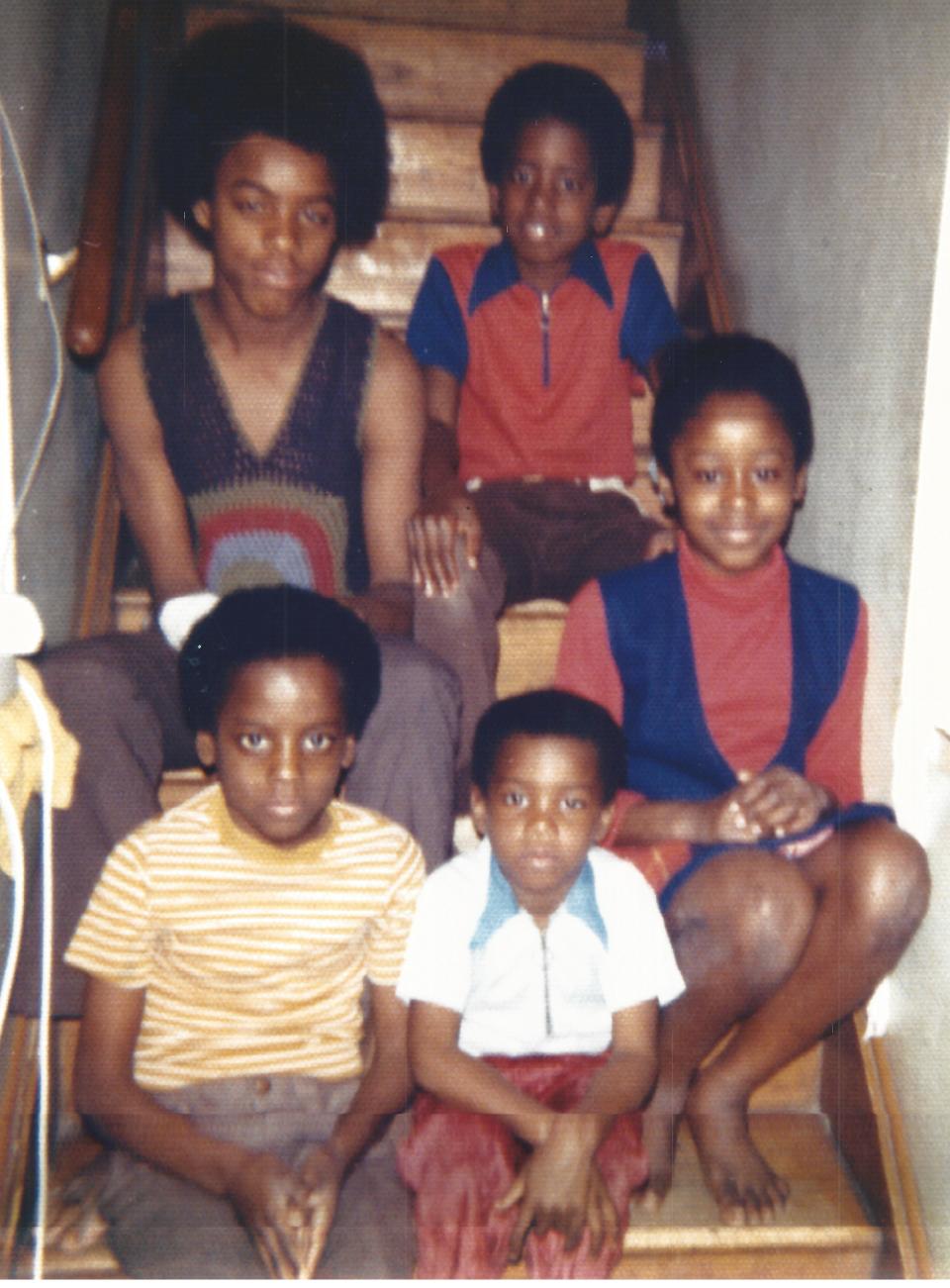

Helen Owens, 57, of Banta, California, told us about how one instance of racism she experiences in childhood stayed with her for the rest of her life. It happened when a friend’s father said he didn’t want his daughter to spend time with Helen anymore, because Helen is black.

“That was the worst thing that ever happened to me, in terms of being a little girl and hearing for the first time that someone really didn’t want me around because my color,” Owens said. “Not because of my character, not because of the person I was, but because I was black.”

Helen said she thinks people don’t like to talk about painful experiences such as hers because they’d rather not acknowledge that racism exists in daily life.

“People are afraid to talk about it because they don’t want the issue to come up,” Owens said. “They don’t want to be called out to say that ‘I look at you different because of what you look like.’”

People can also make harmful assumptions based on race, like inferring that someone doesn’t belong in a particular place.

Shelley Sumpter, 69, of Minneapolis, MN told us a story about how a woman assumed she and her family were in the wrong place due to their race. One day, when Shelley’s family stopped to ask for directions on their way to the cemetery, a woman told them there were no black people buried there and that their family therefore couldn’t be buried there.

“When we got there to the cemetery, she was shocked when we went to place the flowers,” Sumpter said.

Shelley told us that even though the woman wasn’t kind to her at first, Shelley waited for her to see that she was wrong. Now, the two families are friends and keep in touch. Shelley said the woman and her husband place flowers on the graves belonging to Shelley’s ancestors when she and her family can’t make the trip.

“To show that we’re not forgotten,” Sumpter said.

Another reader learned how her white ancestor upheld the peonage system in early 20th century Georgia. When Mary Garvey, 71, of Long Beach, Washington learned that she is related to John S. Williams, an infamous murderer of black fieldhands, she wondered why her family never talked about it and felt ashamed.

Now, Garvey says it’s her obligation to make sure she’s honest about the true version of her family’s history.

“Sometimes you have to open up wounds to actually let the sunlight in, so the healing can at least start”

Garvey tries to grapple with her family’s past and with the country’s past as a whole. She tries to recognize the land that Americans took from Native Americans and wants to see more people acknowledge painful truths like her own family story.

Helen Owens also says that people need to turn toward themselves so that a national healing process can begin.

“When people understand or they’re able to understand who they really are, not just from the outside, but form the inside, we all do better,” Owens said.

When we share stories about ourselves and our pasts, we get closer to understanding a truer and more accurate version of country’s history.

To hear the full audio story featuring Mary Garvey, Helen Owens, and Shelley Sumpter, click here.

In 2020, reparations are one way that people say we can acknowledge harmful truths about our past deeds. To learn more about the debate over reparations and the steps some groups are taking, read Deborah Barfield Berry’s story about reparations, Antigua, and Brown University.

Find more stories from USA TODAY’s 1619 project at 1619.usatoday.com. For more black history content in February and beyond, visit the page at blackhistory.usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Three women's personal stories are helping re-tell black history