States cut Medicaid as millions of jobless workers look to safety net

States facing sudden drops in tax revenue amid the pandemic are announcing deep cuts to their Medicaid programs just as millions of newly jobless Americans are surging onto the rolls.

And state officials are worried that they’ll have to slash benefits for patients and payments to health providers in the safety net insurance program for the poor unless they get more federal aid.

State Medicaid programs in the previous economic crisis cut everything from dental services to podiatry care — and reduced payments to hospitals and doctors in order to balance out spending on other needs like roads, schools and prisons. Medicaid officials warn the gutting could be far worse this time, because program enrollment has swelled in recent years largely because of Obamacare’s expansion.

The looming crisis facing Medicaid programs “is going to be the ’09 recession on steroids,” said Matt Salo, head of the National Association of Medicaid Directors. “It’s going to hit hard, and it’s going to hit fast.”

Medicaid programs, among the largest budget items in most states, provide health insurance to roughly 70 million poor adults, children, the disabled and pregnant women. The federal government on average pays roughly 60 percent of program costs, with poorer states receiving a higher share. States have the latitude to adjust benefits, payments to health care providers and eligibility requirements with oversight by the federal government.

Now, governors are turning to Congress for help as it weighs a new package to rescue state budgets battered by the pandemic. They’re asking lawmakers to provide a bigger boost to Medicaid payments and provide hundreds of billions of dollars in aid to shore up state budgets.

Medicaid naturally faces heightened demand as economic conditions worsen. But that leaves states facing more need at the same time that they have less money.

“The cruel nature of the economic downturn is that at a time when you need a social safety net is also the time when government revenues shrink,” Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, a Republican, said Tuesday as he announced $210 million in cuts to his state’s Medicaid program in the next two months.

The vast majority of a $229 million spending cut made by Colorado Democratic Gov. Jared Polis last week came from Medicaid, though new federal funds will forestall an immediate reduction in benefits or payments to health providers. State legislative committee staff have warned Medicaid enrollment there could spike by 500,000 by the end of the year.

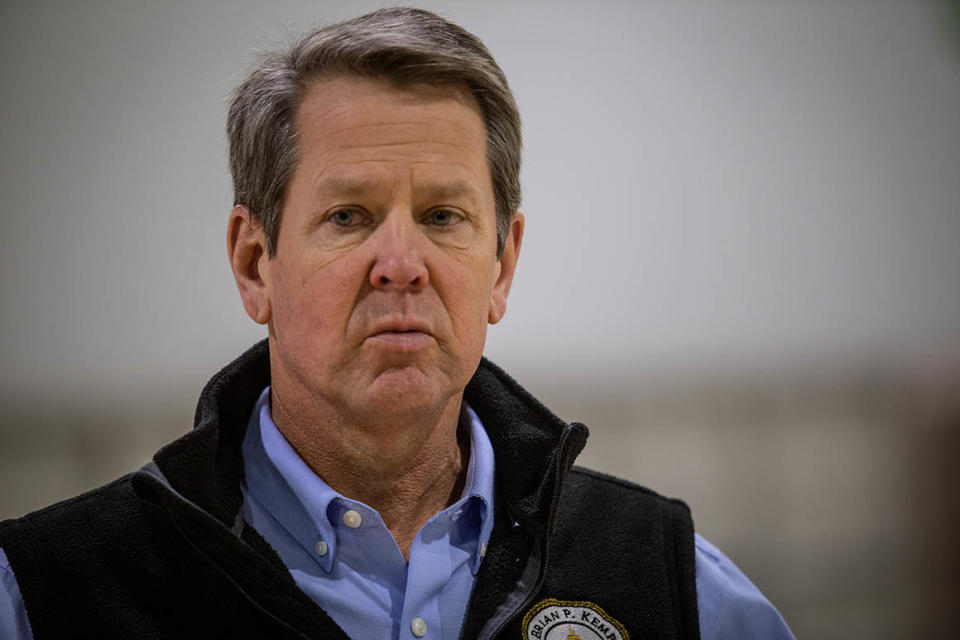

In Georgia, where Medicaid enrollment is projected to rise by as much as 567,000, Republican Gov. Brian Kemp and legislative leaders have instructed every state agency to prepare for 14 percent reductions across the board.

House Democrats are pushing to deliver a $1 trillion-plus package in aid to state and local governments and to support safety net programs, which could alleviate pressure on states to make deep cuts to health care during a pandemic. Some Republican lawmakers have questioned the need for more aid, after Congress has shoveled out trillions of dollars in rescue funding.

Congress already gave states a temporary 6 percent increase in the federal portion of Medicaid spending in an earlier coronavirus package. That prompted Alaska Gov. Mike Dunleavy, a Republican, to cut state Medicaid spending $31 million last month, saying the temporary federal boost would make up the difference.

State officials largely agreed the increase was helpful but said it likely will be washed out by an expected enrollment surge. The nation’s governors say Congress — in addition to providing at least $500 billion in direct support to states — must double the Medicaid funding boost to 12 percent as it did in the previous recession. At least one Republican senator facing a tough reelection fight, Cory Gardner of Colorado, said his state sorely needs extra Medicaid funding to avoid “harmful budget cuts.”

Anywhere from 11 million to 23 million more people could sign up for Medicaid over the next several months. The demand will be even greater in roughly three-quarters of states that expanded Medicaid enrollment to poor adults under the Affordable Care Act.

The portion of state budgets devoted to Medicaid spending has grown quickly since the previous recession, making it a riper target for cuts. Medicaid spending on average accounted for 15.7 percent of state budgets in fiscal 2009, a number that jumped to 19.7 percent in fiscal 2019.

Medicaid enrollment data in some states often lags, making it difficult to determine how much national sign-ups have climbed since jobless claims began surging two months ago. Some states have begun to report notable surges, however, and larger increases are expected in the coming months.

Arizona in the past two months saw 78,000 people enroll in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, which receives more generous funding from the federal government. Virginia has seen a 20 percent increase in enrollment applications since mid-March.

In New Mexico, where 42 percent of the population was already enrolled in Medicaid, sign-ups in the first two weeks of April surged by about 10,000 more people than were expected before the pandemic.

New Mexico’s top Medicaid official said the budget is a significant concern for a state heavily reliant on oil and natural gas. She worries a prolonged economic downturn could force the state to roll back pay increases to Medicaid providers enacted last year, and another planned pay raise for next year is almost certainly off the table.

States that accepted the temporary Medicaid payment increase from Congress are barred from cutting back enrollment while they’re receiving the enhanced funds. That leaves states with the option of cutting benefits or provider payments to find Medicaid savings, which could ignite fierce brawls in state capitals.

Michigan state Rep. Mary Whiteford, the Republican chairwoman of a health care appropriations panel, said the state’s Medicaid enrollment could increase from 2.4 million to 2.8 million by the end of the year.

“We are just planning for major cuts moving forward,” Whiteford said.

Before the pandemic, states had socked away $72 billion in rainy day funds — an all-time high, said Brian Sigritz of the National Association of State Budget Officers. But that figure was easily dwarfed by the $150 billion Congress provided to state and local governments in an earlier package, and it’s far short of what states are demanding.

“Now, we’re looking at greater declines than what we saw during the Great Recession and increased spending,” Sigritz said. “If there aren’t more federal funds, states will have to look at cutting funding for key services: public safety, education, health care. That’s where the money is.”