‘Soul of the Underground Railroad’: David Ruggles, the man who rescued Frederick Douglass

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the dead of a cold December night, David Ruggles woke up to the sound of a commotion outside his front door.

Then, the pounding started.

A voice outside asked, "Is Mr. Ruggles in?"

"Who are you?" Ruggles responded.

"A friend – David, open the door," the man said.

Ruggles knew there was no friend outside, only danger.

The year was 1836, and though he was a free Black man living in New York City, nearly 150 miles north of the Mason-Dixon line, he could never be entirely safe from the surreptitious band of slave catchers that prowled the city.

And his reputation as an abolitionist, together with his visit days before to an illegal slave ship to determine if enslaved people were on board, made him a prime target that night.

Ruggles refused to open the door. Once the men left, Ruggles escaped into the frigid night.

In the 1800s before the Civil War, New York was a dangerously unpredictable place for Black Americans to navigate. Fugitive slaves had been escaping to the city for decades, blending in with a small population of free Black people to avoid capture. By 1804, most northern states had passed laws ending slavery. But free Black people remained second-class citizens. And their freedom was precarious: At any given moment, they could be arrested and either returned to their owners or sold into slavery.

Against this backdrop, Ruggles emerged as a brash, outspoken activist who fiercely stood up against white supremacy. Nearly two centuries after his death, his legacy remains obscure despite a range of accomplishments that few historical figures can match.

This series explores the unseen, unheard, lost and forgotten stories of America’s people of color.

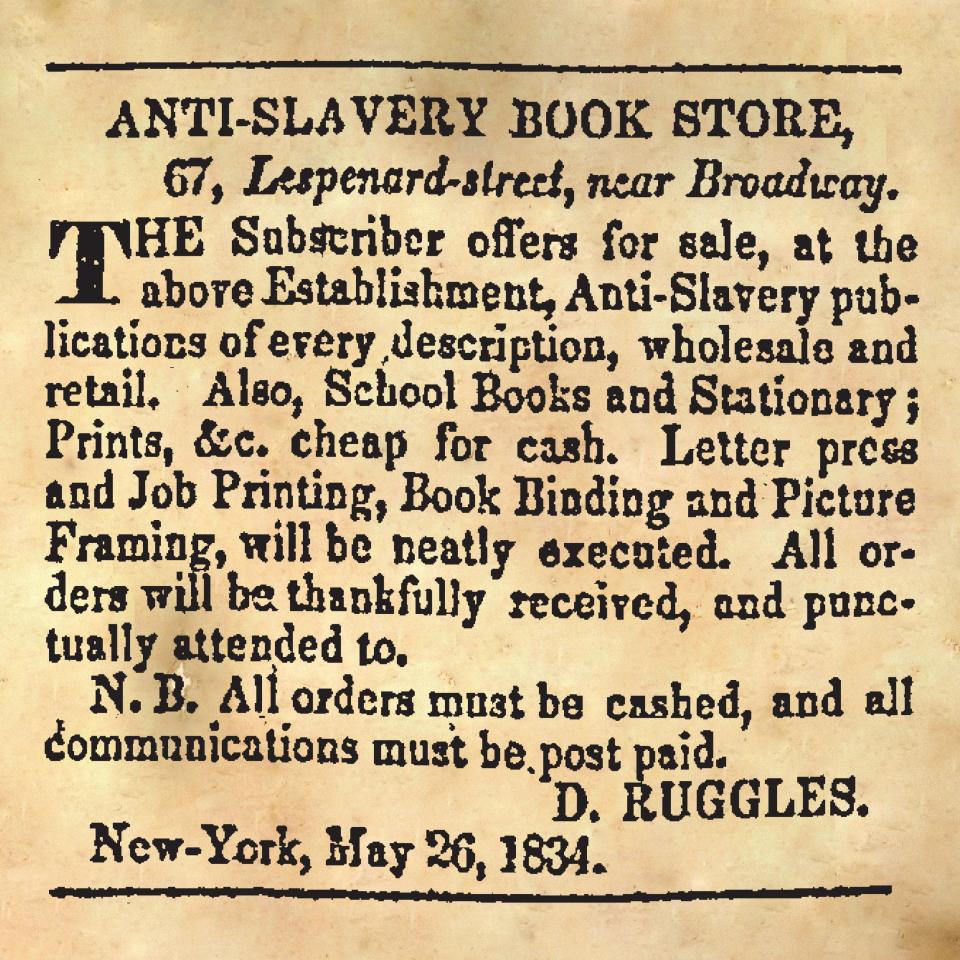

Ruggles owned a grocery store and the first Black-owned bookstore, filled with antislavery literature. He founded his own magazine to advance the abolitionist cause.

Decades before Ida B. Wells-Barnett exposed the gory details of lynchings, Ruggles was a pioneering investigative journalist who wrote about free Black people being kidnapped and forced into slavery. One century before Malcolm X emerged as a fiery critic of American values, Ruggles was a gifted orator who inspired audiences to care about the liberation of slaves. And long before Harriet Tubman became the Moses of the enslaved, Ruggles was described as the "soul of the Underground Railroad." He helped as many as 600 enslaved people escape to freedom.

When Frederick Douglass arrived in New York as a frightened, penniless fugitive from Baltimore, it was Ruggles who gave him money and shelter, and who eventually became his mentor.

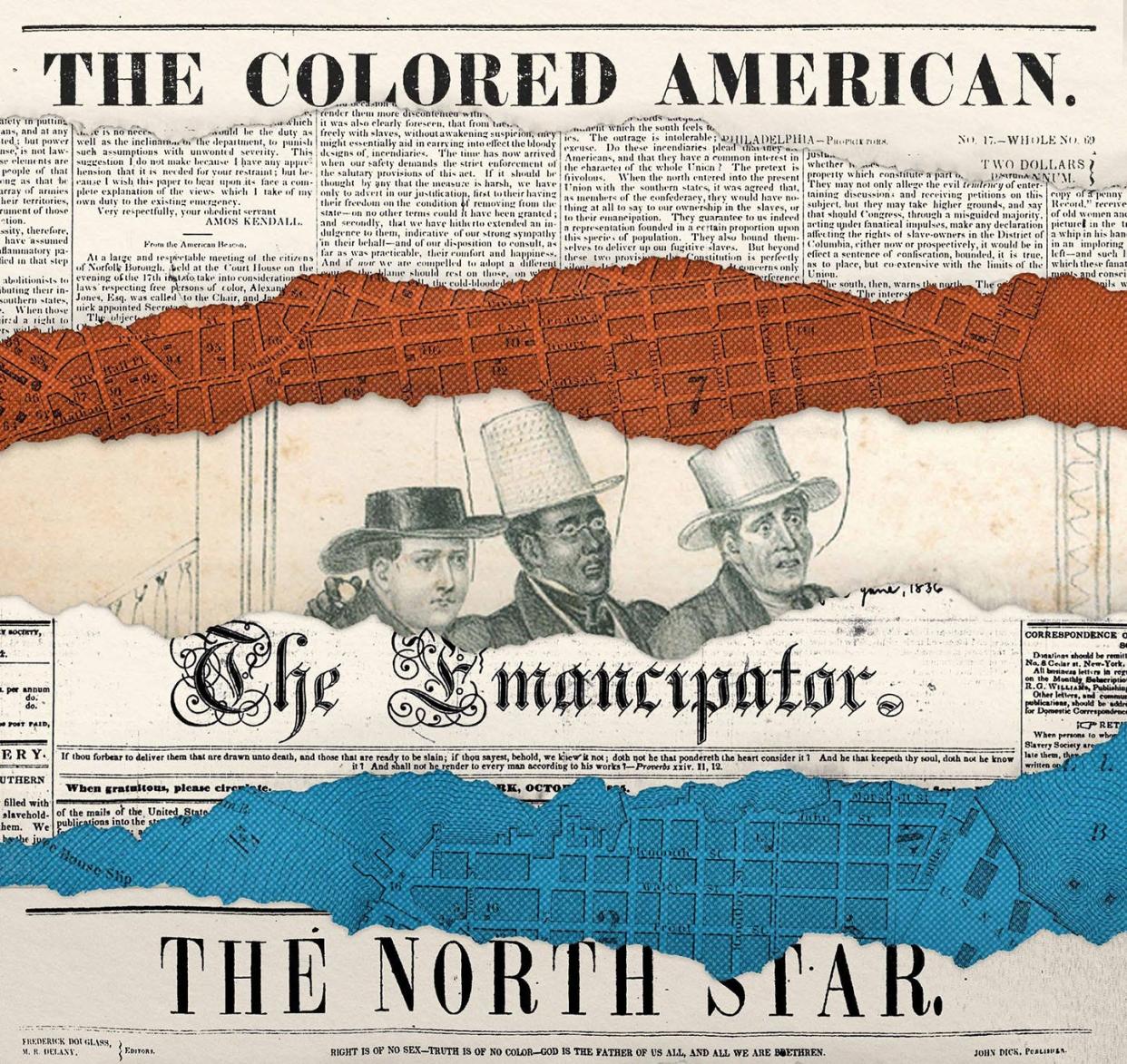

Unlike these heroic people whose lives and accomplishments are well-documented, Ruggles' life and work remain buried in centuries-old newspapers and pamphlets. To stitch his life together, USA TODAY combed through thousands of pages in dozens of antislavery publications. These include Freedom’s Journal, the nation's first Black newspaper started in 1827; The Liberator, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison’s famed 1831 newspaper; and The Emancipator, the newspaper whose 1833 inaugural publication galvanized the abolitionist movement in New York state.

Ruggles ultimately paid a steep price for his activism, exhausting himself and burning out way too soon. He died blind and ill at 39, never acquiring much fame or fortune.

“Ruggles' relentless, uncompromising vigilance against kidnappers and deeply humane assistance to Blacks fleeing slavery make him a model for any American battling for our freedoms,” said Graham Hodges, a history professor at Colgate University in New York. "He showed that journalism counts and that writing is fighting."

How Ruggles became an activist

Ruggles’ dedication to the antislavery movement followed his upbringing as a free Black person who once wrote that he spent his “happiest hours” as a child playing with both white and Black kids. If he had any doubts about his status as a second-class American, a single incident one icy January morning in 1834 erased them.

Shielded from the winds lashing off the Hudson River, Ruggles was sitting comfortably inside a stagecoach as he prepared to travel from New York to Newark, New Jersey, for business.

As the stagecoach headed toward the ferry that would ultimately transport Ruggles to Newark, it stopped to pick up a white female passenger. The driver told Ruggles to move outside to sit next to him so that she could sit inside.

"Why, I have paid my fare to Newark, and I wish to keep my seat," Ruggles responded, refusing to move.

"Yes, you are unfortunate to be colored, it's true ... and it is against my rules to allow colored men to ride inside," the driver told Ruggles.

Incensed by Ruggles' refusal, the driver entered the stagecoach with "the ferocity of a tiger, and with his hands like claws tore (Ruggles') clothes, buttons and skin."

The driver and another white man shoved him into the street.

"He had … trampled upon my feelings, and he was robbing me of my rights, my liberty, my all," Ruggles wrote three days later in the Emancipator newspaper.

The incident deeply wounded a 23-year-old Ruggles, who entered the world as a free Black child born March 15, 1810, to two free Black parents in a small, rural village near Norwich, Connecticut. The state had passed an act for the gradual abolition of slavery in 1784, setting clear rules and regulations for the eventual freedom of Black people. The year Ruggles was born, a volume of local history notes, only 8% of the 164 Black people in Norwich were enslaved.

In one of several antislavery pamphlets he wrote, Ruggles fondly recalled his childhood when “Black and white children would swim through the beautiful silver streams. They would climb the tall pine and oak trees and ramble the fine orchards for sweet fruits. And in the winter they would skate on the icy ponds until the school bell rang.”

After this integrated upbringing, Ruggles made his way to New York in 1827, where at age 17, he worked as a mariner. When Ruggles arrived in New York, a new, empowered generation of Black abolitionism was about to blossom. Two Black men, Samuel Cornish and John Russwurm, launched Freedom’s Journal.

“Too long have others spoken for us,” the co-editors wrote in the publication’s first issue in March 1827. “Too long has the public been deceived by misrepresentations in things which concern us dearly.”

Though more antislavery newspapers were started in the late 1820s and 1830s, Freedom’s Journal was “an essential catalyst” for a rising generation of abolitionists, Harvard historian Timothy Patrick McCarthy said.

Black people were now able to fight for freedom and racial equality not only with their blood but with their words.

“The abolitionists were America’s first culture warriors,” McCarthy said. “And print culture, especially for Black abolitionists, was one of the great weapons in their arsenal.”

Manisha Sinha, a history professor at the University of Connecticut, said the emerging Black abolitionists in this period were engaged in a “two-pronged fight.”

“I think it’s really important for us to understand that for free Black people, this fight was personal,” Sinha said. “They were fighting against slavery in the South, but they were also fighting against racism at home. They faced segregation in every walk of life.”

The establishment of the Black press was right on time for Ruggles, who would later emerge as a gifted writer.

“Ruggles operated at a time when his words sparked angry and dangerous reactions in a society still devoted to slavery,” said Hodges, who wrote the only full-length biography of Ruggles.

But it would take him a few years to step into his role as a leading abolitionist. Two years after moving to New York, Ruggles abandoned his career as a mariner and opened a grocery store praised for its high-quality goods.

The grocery business provided Ruggles a livelihood, but he became increasingly more interested in the plight of Black people. Following the stagecoach incident in 1834, Ruggles left his grocery business to work full-time as an agent for The Emancipator. Ruggles was the spokesman for the paper, traveling and promoting the publication and its message, hoping to procure new subscribers.

In this role, Ruggles stepped deeper into the abolitionist movement. He began to flex his intellectual muscle as a speaker. He could not financially support himself working exclusively as an agent for the Emancipator so he also became an agent for The Liberator, the most prominent antislavery newspaper in Boston. But he had other ambitions.

Ruggles opened the first Black-owned bookstore in the country in 1834, selling antislavery publications.

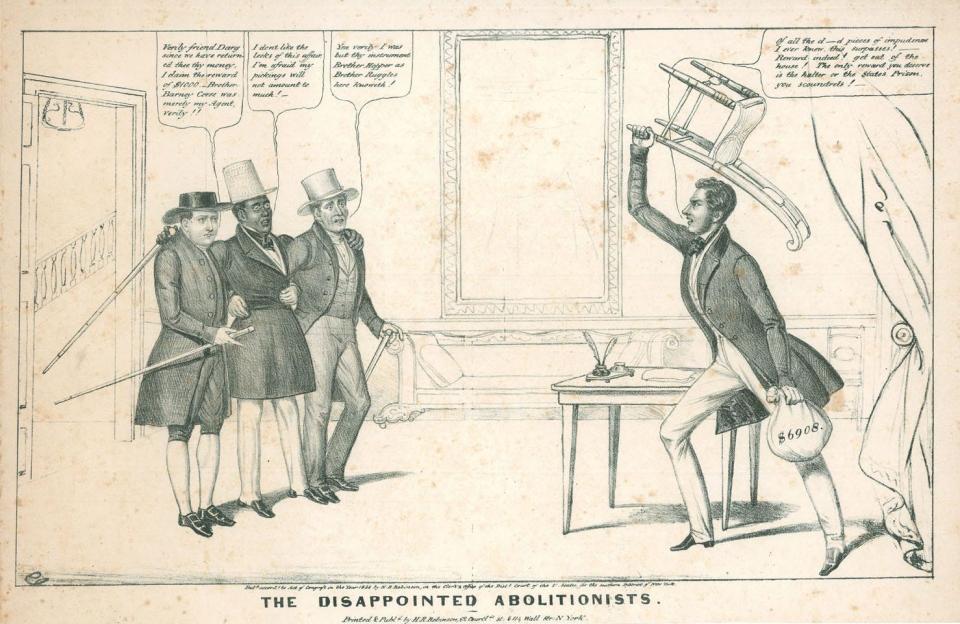

That same year, a series of antiabolitionist riots swept through New York, bringing the city the worst violence it had ever experienced to that point. Fueled by newspaper articles and a disdain for a burgeoning antislavery movement, mobs swept through the city terrorizing Black people and abolitionists for "ten days of wanton brutality and destruction."

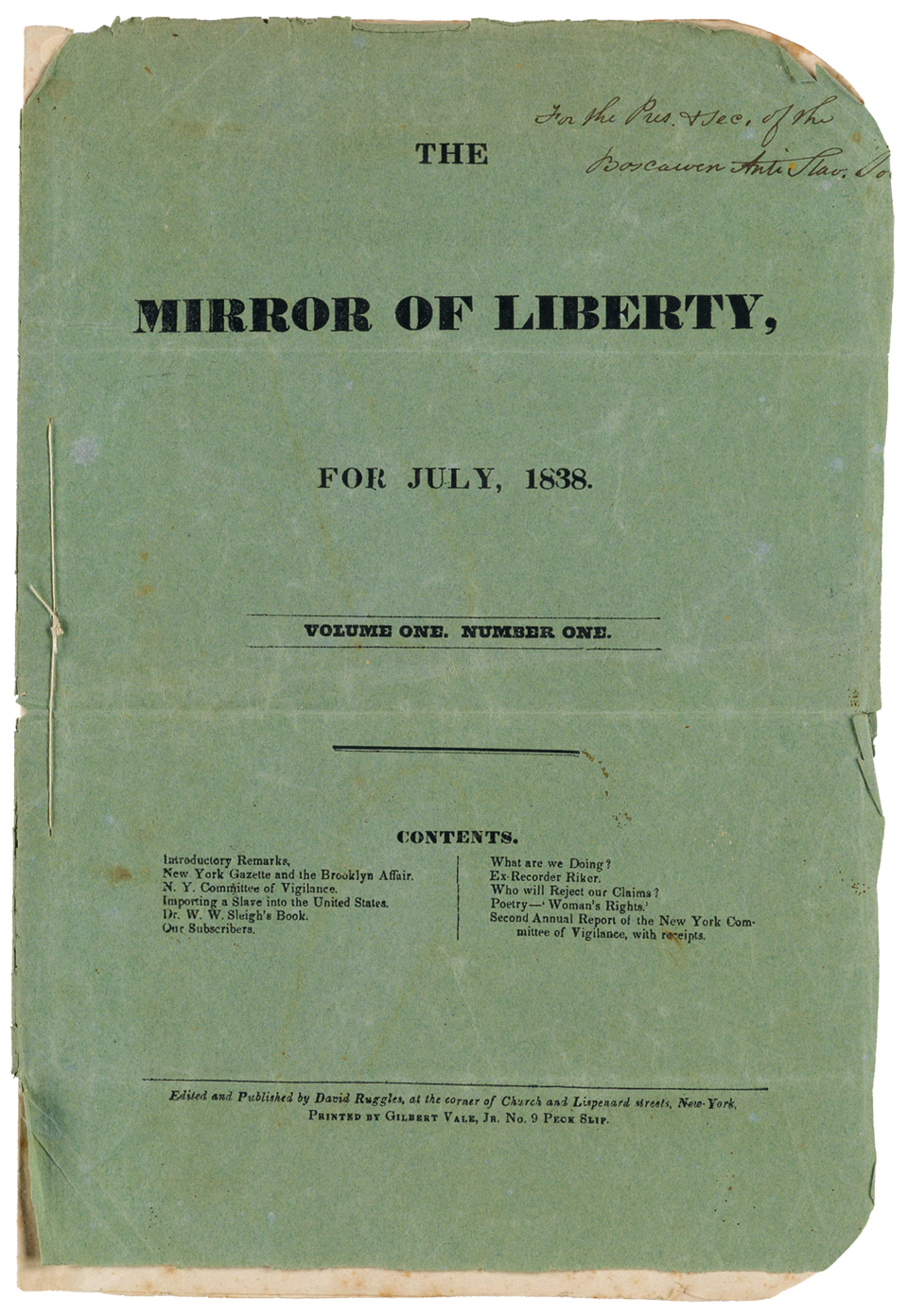

The riots fired up Ruggles’ commitment to the antislavery movement. At 25 years old, Ruggles published his first of five pamphlets, and later started a magazine titled The Mirror of Liberty.

“This was an important historic achievement,” Hodges said. “This is widely considered the first Black magazine in the country.”

In 1835, Ruggles published a series of articles appealing to the media and the public to become more active in the fight against slavery. He spoke and wrote more regularly by this time, amplifying his reputation in the antislavery movement only decades before the Civil War.

Ruggles' bookstore burned down in September 1835 following a series of protests by white citizens. Ruggles offered a $50 reward for information and $25 for details about those who gathered in front of his store immediately before the fire, but no one was ever arrested.

An attempted kidnapping

When the gang of men showed up at Ruggles’ front door that December night in 1836, he had already established himself as a force to be reckoned with. A few weeks before this incident, a small ship carrying five enslaved Africans stealthily navigated its way into the Port of New York. Hearing about an illegal slave ship docked in a free state, Ruggles investigated. He visited the ship several times during daylight and once he confirmed that slaves were onboard, Ruggles had the ship's captain arrested. But the captain was discharged, which infuriated Black New Yorkers.

After the captain's release, "a gang of negroes, some of whom were armed," boarded the ship, assaulted the crew, threatened them with a pistol and took two slaves away, Ruggles would later write.

Whether they suspected Ruggles was involved or simply wanted to make an example of him, a group of slave catchers, including a New York police officer, devised a plan to punish Ruggles for his outspokenness. It was this mob, armed with weapons, that visited Ruggles' home between 1 a.m. and 2 a.m., with local marshal Daniel Nash banging on Ruggles’ door. Ruggles wrote an account of this incident for several publications, including the New York Weekly Advocate.

Ruggles told Nash that he was there at an "unreasonable hour" and to call him in the morning.

"Open this door, or I will force it open," Nash said. But Ruggles refused so Nash and his posse rushed to obtain a warrant from the city's chief of police and returned to Ruggles’ home after he had escaped. The landlord told Ruggles that once inside, the men threatened her with clubs, pistols and daggers.

Then they rushed up to Ruggles’ bedroom like a pack of “hungry dogs,” Ruggles wrote. One of the intruders brandished a knife and threatened to "put an end to his (Ruggles’) existence” but found that Ruggles was not there.

The following day, he was charged with igniting the riot on the slave ship. But the false allegation didn't hold up, and he was released. Still, Ruggles was certain the mob had every intention to sell him into slavery.

"(I) take fresh courage in warning my endangered brethren against a gang of kidnappers, which continues to infest our city and the country, to kidnap men, women and children, and carry them to the South," Ruggles wrote in the Advocate.

Ruggles' narrow escape from slavery didn’t dampen his commitment. Through the first half of 1837, Ruggles exposed the crisis of slave catchers abducting free Black children and selling them into slavery. In several antislavery publications, he would publish the names and descriptions of the kidnapped free Black people and fearlessly publish details about slave ship captains. Despite the risks, he provided his home address as a location where readers could report details about any kidnapped person.

Ruggles reported the abduction of Frances Maria Shields, a 12-year-old dark-skinned girl last seen wearing a purple and white dress. In addition, he alerted the public about John Robinson Welch, an 8- or 9-year-old boy, who disappeared from his home. There was also Thomas Bryan, a free Black boy who was jailed in Vicksburg, Mississippi, about to be sold to recoup his jail fees. Another free Black male, Thomas Oliver, was kidnapped and sold as a slave in New Orleans.

Ruggles shined as an investigative reporter who had his pulse on the kidnapping community. But the work began to take a toll on Ruggles, and he announced that he would take some time off.

“Though declining health compelled me to retire from the city and take refuge in the country, my heart is with you in the cause of Freedom,” a 27-year-old Ruggles wrote in the Colored American, another Black-owned newspaper, in September 1837.

Fortunately for one famous slave, Ruggles didn’t take a step back. He would soon play a pivotal role in freeing one of the most famous activists in American history.

The rescue of a famous fugitive slave

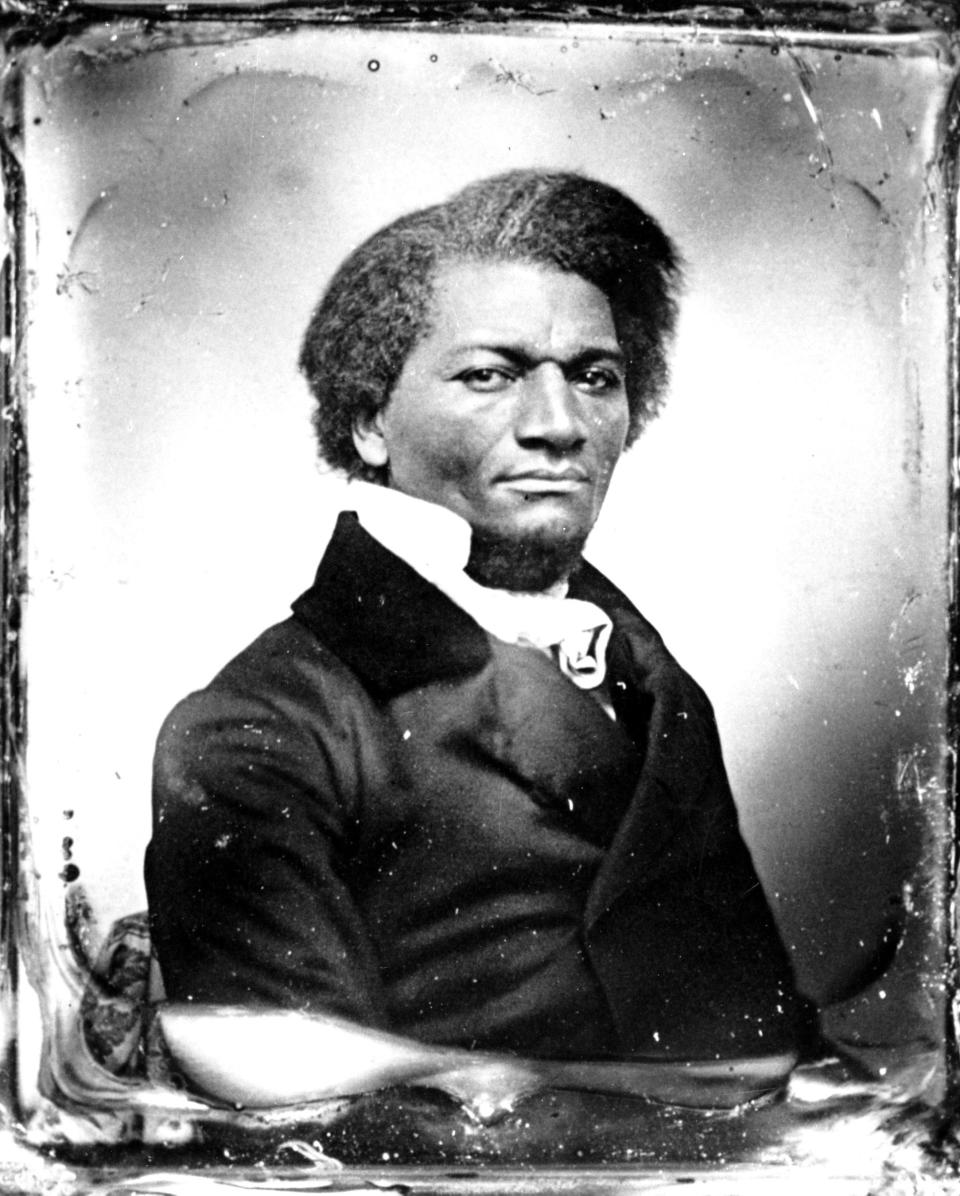

A fleeting feeling of euphoria crept over Frederick Douglass when he first arrived in New York in 1838, having escaped slavery in Baltimore by disguising himself as a sailor and hopping aboard a train. Finally a free man, Douglass wrote in his 1845 autobiography that he felt like he “escaped a den of hungry lions.”

But stranded on the docks, poor and homeless, Douglass was quickly overcome with loneliness.

“There I was in the midst of thousands, and yet a perfect stranger; without home or friends,” Douglass wrote.

After a few days, Douglass did find a friend – Ruggles. Ruggles took Douglass in and helped Douglass' girlfriend, Anna, get to New York, where he witnessed the two get married. After the wedding, Ruggles gave the couple $5 and the Douglasses boarded a steamboat to Massachusetts.

"He was a whole-souled man, fully imbued with a love of his afflicted and hunted people, and took pleasure in being to men as ... eyes to the blind and legs to the lame," Douglass wrote about Ruggles.

Douglass might have been Ruggles' most recognizable beneficiary. By this time, Ruggles’ reputation as an emancipator was well-established. But his health, always fragile, continued to decline.

Nearly blind and walking with a cane, a young Ruggles, only in his early 30s, retreated from New York City to Northampton, a small, rural Massachusetts town in 1842.

Ruggles suffered from an enlarged liver, irritated lungs, chronic inflammation of the bowels, nervous and mental debility. At age 32, Ruggles’ doctor only gave him a few weeks to live. Ruggles detailed the ailments he suffered in an article published in the National Anti-Slavery Standard in 1848.

After trying a variety of drugs and physicians, Ruggles turned to an alternative form of medicine called hydrotherapy. His water treatment consisted of taking several baths and wrapping himself in wet sheets.

Ruggles became consumed with hydrotherapy, and in two years he began to practice hydrotherapy himself. With the aid of friends, Ruggles built his own medical compound at his new home in Northampton.

“When you think about the utter and complete racism at the time, here’s this guy who’s able to convince these flint-hearted, very astute Yankee investors to put money into him,” Hodges said. “For them to invest their money into his hospital, he had to have a considerable presence. This was not an easy process.”

Ruggles dedicated himself to healing others, but he couldn’t heal himself. On Dec. 16, 1849, with his hospital filled to capacity, Ruggles died.

News of Ruggles’ death spread, with those who intimately understood his contribution to antislavery celebrating his legacy in the newspapers.

“The memory of the just shall live, and thousands who have escaped the yoke of slavery by his aid will never cease to remember this faithful friend of the slave, and lover of mankind – with grateful admiration,” Douglass wrote about Ruggles in his newspaper, The North Star, days after he died.

Garrison, the renowned white abolitionist, said Ruggles deserved to “be ranked amongst the benefactors of his race.”

“He conquered obstacles, he performed exploits, he encountered perils and sufferings, in the spirit of a hero, and with the courage of a martyr,” Garrison published in the Liberator five days after Ruggles' death.

Today in Northampton, there is a modest museum named for Ruggles.

"His history was completely forgotten for generations, said Tom Goldscheider, the education coordinator at the David Ruggles Center for History & Education. "So, one of the primary missions of our museum is to make sure his legacy is acknowledged. We'd just like him to get the recognition he deserves."

Few people understood just how much Ruggles accomplished in his short life more than Douglass, who wrote of Ruggles: “He has literally worn himself out in humanity’s service – ever ready to do with his might whatever he could for the benefit of the race.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Activist David Ruggles fought kidnappers, helped free 600 slaves